Bialowieza Puszcza: Europe's Last Primeval Forest

Bialowieza Puszcza

Grey Wolves in Bialowieza

Heck Cattle

A Useful Link

- Białowieża National Park Travel Information and Travel Guide - Poland - Lonely Planet

Travel and Tourism Information for Bialowieza

The Puszcza

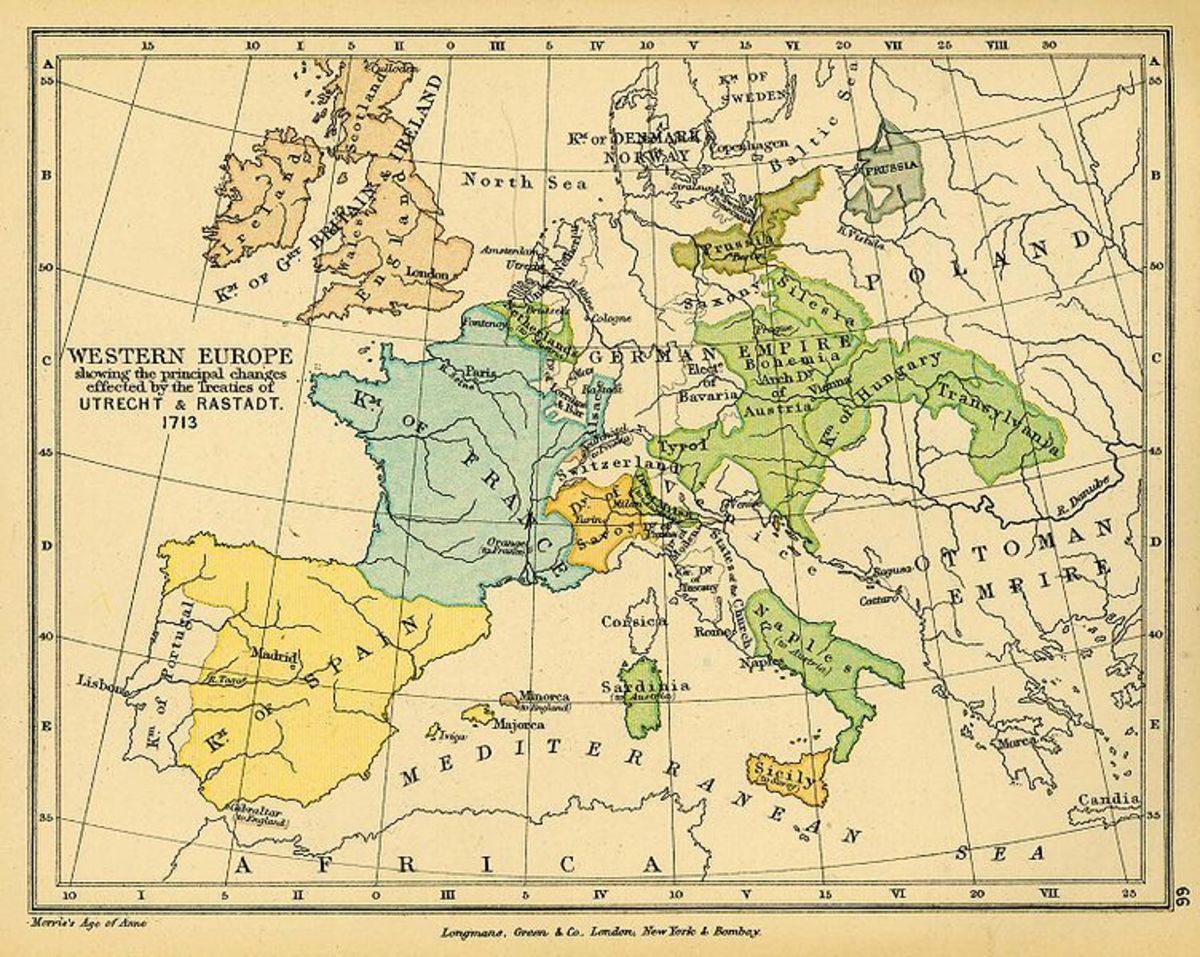

Tucked away in a far flung region of Eastern Europe is a vast forest of half a million square acres that straddles the border between Poland and Belarus. At first glance, it may seem just like another forest, but I can assure you, it is very, very special. The tiny village set in the forest’s heart of is called Bialowieza, it lends its name to the forest, and most people refer to it by that name, although the locals give it a different name, ‘Puszcza’ which means ‘forest primeval’, and to call it primeval is nothing short of an understatement. The Puszcza is the last fragment of a once great cloak of forest that stretched from Ireland in the west, almost all the way to Siberia in the East. To those born in areas of the world where deciduous forest occur, when you enter the Puszcza, you realise that you have taken a step back into the past, to a time before agriculture, to when our hunter gatherer ancestors roamed the great forest, foraging for Berries and Plants, hunting wild boar and wild cattle and evading dangerous predators like wolves and bears.

One way of envisaging the Puszcza is to think of those forests you remember from fairy stories; imagine towering ash and linden Trees stretching 150 feet from the forest floor, sheltering a dense, tangled undergrowth of hornbeams, ferns, alders and fungi that can reach the size of dinner plates. Imagine oak trees, covered in moss that has accumulated over centuries and with trunks so vast, that great spotted woodpeckers can store spruce cones in its three inch deep bark furrows. What’s so amazing about the Puszcza is, not only is a last tiny fragment of a once great forest, but also, unlike other wild areas of Europe, it doesn't gain protection from a mountain or any other impassable barrier that prevented human colonisation. Bialowieza lies on lowland, which ordinarily would have been ideal for farming, it’s just that, in this case, the loggers have never bothered to cut it down, and thank goodness for it.

It’s really quite staggering to think, that once all of Europe looked like this; to realise that most of us that live in the temperate parts of the world are left with just a pale copy of what nature truly intended, we are used to entering heavily managed forests, that, at times can feel disturbingly empty and devoid of any vibrancy and sense of health. In the Bialowieza the sheer abundance of life owes much to all that is dead, in a healthy forest, more than half the wildlife lives off rotting timber. Virtually every acre of the Puszcza is littered with decomposing trunks and fallen branches that help nourish thousands of species of mushrooms, lichens, bark beetles, grubs and microbes that are sadly missing from the heavily managed forests found elsewhere.

These species help to form the foundations of the healthiest ecosystem to be found on the European continent, the Mammal species include: weasels, stoats, pine martens, badgers, otters, beavers, wild cats, red foxes, lynx, wolves, roe deer, fallow deer, red deer, elk (moose), wild boar and brown bears, which have been reintroduced back into the forest after a lengthy absence. It’s the only forest on the entire continent, where the keen birdwatcher can look out for all nine species of woodpecker to be found in Europe, because some species only nest in hollow, dying trees, they cannot survive in managed woodlands elsewhere. A keen birdwatcher may also gasp at the sight of white tailed eagles and golden eagles soaring majestically over the thick canopy, we often think of eagles as being denizens of mountain country, but in reality they are more at home in the lowlands. Golden eagles took to the mountains, because they require vast territories stocked with prey, and also to escape the attentions of man. There are also goshawks, swooping swiftly and with great agility through the smallest gaps between the great trunks of trees, several centuries old at least; also the honey buzzard, much rarer than the common buzzard, and one of the few raptors willing to tackle a wasp or hornets nest in order to secure food.

The Puszcza is also home to larger mammals; living in large enclosures you’ll find Heck cattle, these creatures are relics of Hitler’s obsession with mythology. He desired that the extinct aurochs, the ancestor of domestic cow be resurrected. The task was left to two German brothers Dr. Heinz Heck and his brother Lutz, also a Doctor, who managed to ‘create’ the Heck breed by crossbreeding various hardy breeds with Spanish fighting bulls, to mirror the aurochs famed bad temper. Alongside the Cattle, live Konik ponies, descendants of the Wild tarpan that once roamed right across Europe. The wild tarpan became extinct in the mid 19thcentury, but the Koniks’ serve as living link, as the last pure individuals were cross bred with primitive domestic Horses. Bialowieza is also home to the largest land mammal to be found in Europe, the European bison or wisent; it was virtually hunted to extinction in the wild, but a small number survived in the depths of the forest, thanks to intensive conservation, the bison population multiplied and was eventually the source for efforts to reintroduce the species into other areas of its former range, including the Caucasus Mountains. They are similar to their American cousins, except that the wisent tends to stand taller and focus more of its time on browsing rather than grazing.

Konik Horses

The European Bison or Wisent

King Wladyslaw Jagiello of Poland

History of the Forest

The Puszcza can trace its origins to the aftermath of the Ice Age, after the great glacial ice sheets completed their retreat back to their Arctic stronghold, temperate conditions returned from the south and deciduous forests spread right across Europe, and so did the animals that depended on it. However, within a couple of millennia, this great swathe of green came under attack from Humans who had recently switched from hunting and gathering to farming. By the time of the Roman Empire, Western Europe was largely deforested, with the East providing a stronghold for the wilderness. During the 14thCentury a Lithuanian Duke named Wladyslaw Jagiello allied his Grand Duchy with the Kingdom of Poland and declared the forest, a royal hunting preserve, and for centuries that’s how it remained. When Poland and Lithuania were subsumed by Russia, the forest became a private refuge for the Tsars. During World War One, the Germans briefly occupied it, took lumber and slaughtered game, including almost all of the bison. In 1921, a pristine core of the forest that had never been logged or managed was declared a Polish National Park. The Soviets briefly resumed the pillaging of timber from other areas of the Forest. But when the Nazi’s invaded in 1939, a certain nature fanatic called Herman Goring decreed the entire Forest off limits except for his own pleasure.

After the Second World War, Poland became a puppet of the Soviet Union, so effectively the forest passed into Soviet hands again. However, on one evening in Warsaw, a reportedly drunken Josef Stalin agreed that Poland could retain two fifths of the Forest. After that, little else changed, apart from the construction of hunting dachas (cottages). Incidentally, one of the dachas in the Belarusian part of the Forest became the scene for the signing of the ‘Viskuli’, an accord which, in 1991 dissolved the Soviet Union into a number of Free states, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

In the seven centuries that Puszcza has been owned by either a Monarch, a Tsar or fanatic, it’s the modern post communist era of freedom that sees the forest under its greatest threat. Forestry ministries in both countries tout increased management to preserve the Puszcza’s health. Management, however, often turns out to be the first step towards the culling and selling of mature hard-woods that would otherwise one day return to the earth from whence it came, releasing a windfall of nutrients that would ensure the forest’s survival. It would be shame to lose this forest, because it is not only a window into the past, but a window into our very souls, reminding us where we all came from.

A couple more images of Bialowieza

© 2012 James Kenny