Event Clustering and Stochastic Processes

Random process also occur in multiple dimensions.

Order from Chaos and the Random

Try some simple

experiments. Take some coins and do some coin toss experiments,

keeping a record of results in each case. For the first experiment,

one coin is needed. Do a single toss and see what the result is and

record it. Good! You either have a head or a tail. The law of

averages dictates a 50/50 chance of getting heads and tails. But in

the one coin toss experiment it is either heads or tails, not half

and half. The half and half only describes a probability before the

act is committed, something akin to Schrödinger's question about the

state of his cat in the box with a radioactive element that triggers

a series of events that kills the cat. Now the radiation that

triggers the event can happen at any time, or not at all and that is

why we don't know the state of Schrödinger's cat until we open the

box and look. Until then, the cat to us exists in a curious state

where it is both dead and alive or neither dead or alive. Once the

act of coin toss has been committed, you either have 100 percent

heads or 100 percent tails. There is a tiny chance that the coin will

land on its edge, but this is insignificant.

Next try a

series of coin tosses. You can decide how many it is to be. You

should keep an accurate record of the result of all the single

events. Do this for a lot of single toss events. Make a tally of how

many times it came up heads and how many came up tails. The more you

toss, the closer the totals come into exact agreement of 1:1 or 50

percent of heads and 50 percent of tails. Examine the tally by event

to event and look for trends like several consecutive heads or tails

or even head to tail and back again. Try to find a predictable trend.

Chances are, you will find no such trend. If you do a large number of

runs, each and every one will be different. You will find clusters of

heads only or tails only. You will even find clusters of heads,

tails, heads, and tails. They will not occur in a predictable

fashion.

Now take several coins and toss them simultaneously

and keep a tally on each one. It helps to have different coins to

tell them apart in a tally. You can use a penny, a nickel, dime,

quarter, dollar coin and so forth to tell them apart. The results

will show as above with the tally getting closer to the 1:1 average

with great numbers of tosses. Look for trends as above, but also

across the tallies for different coins. You should begin to

appreciate the nature of random events and stochastic processes.

But

that is not the only thing to look for. You may want to see how many

heads or tails occur at the same time and how they are distributed.

It helps to organize things into columns and rows. The rows can be

labeled penny, nickel, dime, quarter, loony and twonnie for a six

simultaneous event plot. The columns can be numbered 1 to n where n

is the last multiple toss. Although repetitions of the same face can

occur fairly frequently along rows and in columns in the random

number toss, it is rare for all coins to show all heads or all tails.

The more coins you have, the more rare this kind of occurrence is.

Thus it is a rather simple case, especially for a large set of coins.

We can say that as the set gets more complex by way of possibilities,

'coincidental' occurrences decrease.

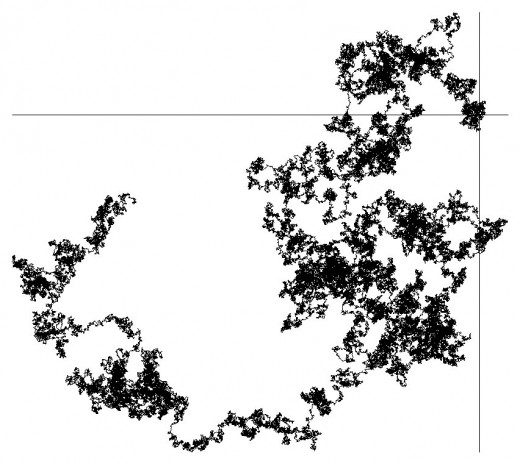

What of more complex

cases where irrational and transcendental numbers are involved

between the continuum of 0 and 1? We know from the laws of

self-affinity, that the cosmos is a very complex place and that

things like coastlines, cosmic dust and other natural phenomena can

be defined as infinite in complexity. We are dealing with very large

scales in this case and thereby reduce the chance of coincidence to a

vanishingly small scale in a purely random way. We could say that as

the scale of length of any system approaches infinity as the scale of

measurement approaches 0. Thus coincidence approaches 0 as any

system's scale in complex length approaches infinity. The rare

occurrences of multiple related and similar events tend to cluster

due to the nature of random processes.

The reader is also

encouraged to experiment with random number sets to determine the

distribution of coincidences for various scales of complexity as in 4

or 5 sets of random numbers between 1 and 100 or 1 and 1,000. We can

say two things! Coincidences will be distributed according to

Guassian definition and how they are rigorously defined. The greater

the spread in numbers being randomly generated, the less chance there

is for coincidences to occur. A coincidence is defined as an event

that is related to another purely by chance or accident. On the

cosmic scale, there are virtually no coincidences, but there are

plenty of "accidents!"

On the other hand, it is

acknowledged that there is a phenomenon such as phase locking where

two systems with slightly different frequencies will tend to move

into resonance. Sensitive dependence also tells us that very tiny

inputs are enough to completely alter the final state after several

iterations of the dynamic. We thus know of systems that diverge with

only very tiny inputs, but the opposite is also true with

convergence, especially if we run things in reverse. Thus phase

locking draws two nearly resonant systems into resonance and gives us

the makings of a 'coincidence'. Such 'coincidences' are like the

clusters of personality types that are governed by certain recurring

planets according to the statistical researches of M.

Guaquelin. Due to the fact that very complex systems are

involved, it is safe to say that pure coincidence is a vanishingly

small reality. In fact, it is safe to say that so called coincidence

is more related to things like phase locking, sensitive dependence

drawing two phenomena into resonance and thus it more properly called

serendipity. Suffice it to say that sensitive dependence and the

interpenetrating influences of each phenomenon upon the rest accounts

for the plethora of coincidences that mere chance cannot.

The

quantum

world is based on such stochastic

events. Here too, we will find clustering events, just like in

the coin tosses. The whole cosmos is built upon the quantum

foundation. Clustering at the quantum level can really add up to the

point of creating super massive black holes.

At the more local

level, we see stochastic processes at work when we experience the

myriad of phenomena that make up our experiences. Almost without

exception, we hear of events by type occurring close together in time

and even locale. The saying that bad or good news comes in groups has

some validity based upon the nature of event clustering. Plane, train

or bus crashes come in groups spaced close together in time,

separated by long periods of no such events. Weather extremes follow

a similar stochastic

pattern. Everyone is familiar with "When it rain's, it

pours" meaning that trouble comes in bunches and the work load

comes all at once, interspersed with quiet periods and calm where one

is forced to look busy to justify their continued employment to the

boss. During the busy period when it all happens it once, it's a

tough go just to keep everything acceptably together. In the anarchy

of the capitalist market, we see this trend at work in the economy

with booms and busts of all sizes occurring in a combined and unequal

fashion.

Even when we look to the formation of solar systems,

we see evolution mediated by forces, random events and harmonics in

synchronicity. Since random events tend to cluster as part of the

natural evolution of the cosmos, it is not surprising to find that

complex systems will evolve as a natural consequence. Planets in

orbit around a star must have orbital periods in dissonance to each

other in order to have reasonable stability. This dissonance will

evolve through time to create patterns that occur randomly in time

where planets cluster along one line of sight or another. Such is the

nature of great stelliums. In our solar system, this kind of thing

occurs roughly once very forty years, but no two stelliums are alike

in planetary grouping, angle of spread or where they are in reference

to the background stars. Since planets orbit in more or less

well-defined periods, these events are highly predictable, unlike the

events in the quantum realm or with coin tosses in a chained sequence

of events.

The long horizon of predictability of planetary

alignments can allow us to determine when events associated with the

planets will tend to cluster as well. Planetary clustering in an

aperiodic fashion will generate aperiodic effects, each upon all

others. Earth is not exempt from the forces of these planets. They

manifest in many ways, obvious and subtle. Some are easy to

understand, others are not. We can calculate the perturbational and

tidal influences with some ease and match these with real effects we

experience. The psychic influences are much harder to track. They are

there nonetheless as evidenced by the lunar and solar influences. The

stochastic and clustering nature of these influences is what is

behind the seeming stochastic and clustering nature of events we

experience.

There are many influences and many events. It is

hard to separate a single effect and link it to a single cause.

Usually, in the complex cosmos, many things occur simultaneously.

With diligent work and research over the long term, we can isolate a

specific result due to a specific influence and then make predictions

to test the observation. Fortunately, there are long records of

various types that allow us to do such detective work. We know for

instance that the eleven-year

solar cycle has been going on for millions of years. Direct

evidence is found in dedrochronological

records for thousands of years and in sedimentary deposits for

millions of years. We also know that the Venus influence on climatic

change has an exact match to ages of ice and warmth on the earth for

a few million years.

The ancients also tracked these events and left an exact record. Notable among these are the Mayan, Egyptian and Vedic accounts. All were avid sky watchers and linked their complexes directly to the sky. The Maya went one step further by recording numerous calendars for the moon, sun, Venus, Mars and the seasons. They uncovered many cycles which they tracked, using the ecliptic and galactic plane as marker points for tabulating cycles as observed from their exactly aligned temple complexes. We know that the moon alone has many cycles and the Maya were aware of the principle ones of the metonic, the tidal, the nodal, the sidereal, synodic and the eclipse cycles. Venus was watched over its 584 day period plus its 8 year less 2 day cycle. They made predictions based on a long history of observations that began with the Olmec and were carried on by them until the Spanish put a halt on it. Thus we can do likewise and make some sense of of event clustering from apparently random events.

The Other Way; Order into Chaos

Evolution of order out of chaos in solar systems

Chaos and Astronomy

- Chaos, Astronomy and Astrology

Ideas that have grown out of recent theories of chaos and complexity have led to a revolution in our view of the universe. Weather studies by Edward Lorentz, for example, illustrate that the tiniest change of...

Random and Stochastic Processes in Print