- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Middle East

Evolution of a Legend: The Life of Cleopatra and Her Ever-Changing Image on Page, Stage, and Screen

History is written by the victors and, less proverbially, the Hollywood filmmakers. In no case is this more evident than in the popular image of the Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra VII. In life, Cleopatra was a shrewd politician whose own propaganda stressed her patriotism and royal descent. However, after her death, Roman depictions of Cleopatra showed her to be a drunken, over-sexed hedonist, an image which was later refined and used in Hollywood films to lend actresses the dangerous, exotic air of the femme fatale. It is this sensationalized image of Cleopatra as an exotic Eastern temptress rather than a wise and loyal mother of her people that has survived to the present day.

The historical Cleopatra was born in Alexandria, Egypt in 69 B.C.E. and raised in a corrupt and violent court in which politically motivated murders were common. Her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes (“the Flute Player”) succeeded to the throne of Egypt after the death of the previous king, his half-brother Ptolemy XI Alexander II, who was lynched after murdering his popular wife, Berenice III, for unknown reasons (Newman 229). Ptolemy later put one of his daughters, Cleopatra’s sister Berenice, to death for attempting to usurp his throne while he was away (Newman 230).

When Ptolemy XII died in 51 B.C.E., he left the throne of Egypt to Cleopatra, then seventeen, and her eleven-year-old brother Ptolemy XIII. The two siblings married in the next year, but in 48 B.C.E. the young Ptolemy, under the advice of his advisors, seized exclusive control of the throne and drove Cleopatra out of Alexandria (Lightman 66, Newman 230). She fled to Pelusium in eastern Egypt, where she raised an army with which to attack her brother (Newman 230).

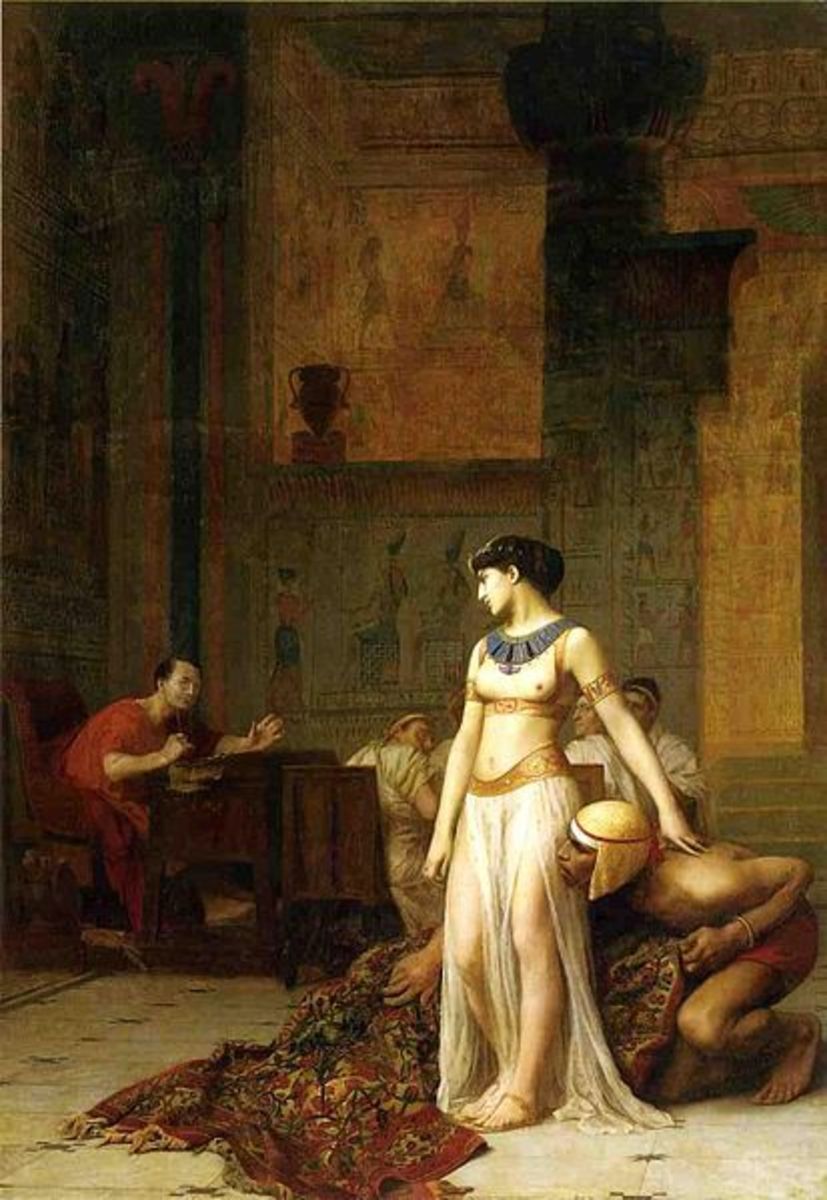

In Pelusium, Cleopatra received a message from Julius Caesar, who had entered Egypt in pursuit of his rival, Pompey. Wrapping herself in bedding, Cleopatra had herself smuggled to Alexandria by boat, where she convinced Caesar to support her claim to the throne (Lightman 66). In the resulting Alexandrian War, Ptolemy XIII was killed, after which Caesar restored Cleopatra to the throne, along with her surviving brother Ptolemy XIV, who became her next husband (Newman 230).

From this point on, Cleopatra utilized connections to Rome, a growing power in the Mediterranean, becoming first Julius Caesar’s mistress and later Marc Antony’s. She bore Caesar one child, Ptolemy Caesar, also known as Caesarion, or “Little Caesar,” and from 46 B.C.E. until Caesar’s assassination in 44 B.C.E., she and her husband lived in his household in Rome (37, Newman 230). Shortly after their return to Egypt, Cleopatra had her brother and husband, Ptolemy XIV, poisoned and appointed Caesarion as joint ruler in his stead (Lightman 67).

In 42 B.C.E., Cleopatra crossed paths with the Romans again when Marc Antony sought to tax the Egyptians to pay for his campaigns in the East (Newman 231). Cleopatra seduced him, and they had three children, the twins Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene and the younger Ptolemy Philadelphus (Lightman 68). After Antony’s return to Rome, he sealed an alliance with Julius Caesar’s heir, Octavian, through marriage to his sister Octavia (Newman 231). However, his relationship with Cleopatra was renewed and intensified in 37 B.C.E., when he again moved eastward through Egypt on campaign. They formed an alliance, with Cleopatra offering Antony military aid in return for rulership of Cyprus, Coele-Syria, and a part of Cilicia (Lightman 68). In 34 B.C.E., after successfully conquering the Armenians, Antony granted Caesarion and his children with Cleopatra control over several of Rome’s eastern territories, and coins were struck with Cleopatra on one side and Antony on the other (Lightman 68, Newman 231).

Finally, after divorcing Octavia in 32 B.C.E., Antony married Cleopatra, after which Octavian declared war (Lightman 68, Newman 231). After Octavian defeated their forces at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E., Antony and Cleopatra both committed suicide, most likely to avoid being paraded in shame in celebration of Octavian’s victory (Lightman 69). Octavian had Caesarion put to death and gave Octavia the children of Antony and Cleopatra to raise herself. This ended the Ptolemaic dynasty and established Egypt as a Roman territory (Newman 231).

In life, Cleopatra had been an intelligent woman, particularly skilled in languages. According to Plutarch, “she had a facility of attuning her tongue… to whatever language she wished. There were few foreigners she had to deal with through an interpreter, and to most she herself gave her replies without an intermediary” (40). Also according to Plutarch, she was the only one of the Ptolemies to master the Egyptian language. (40)

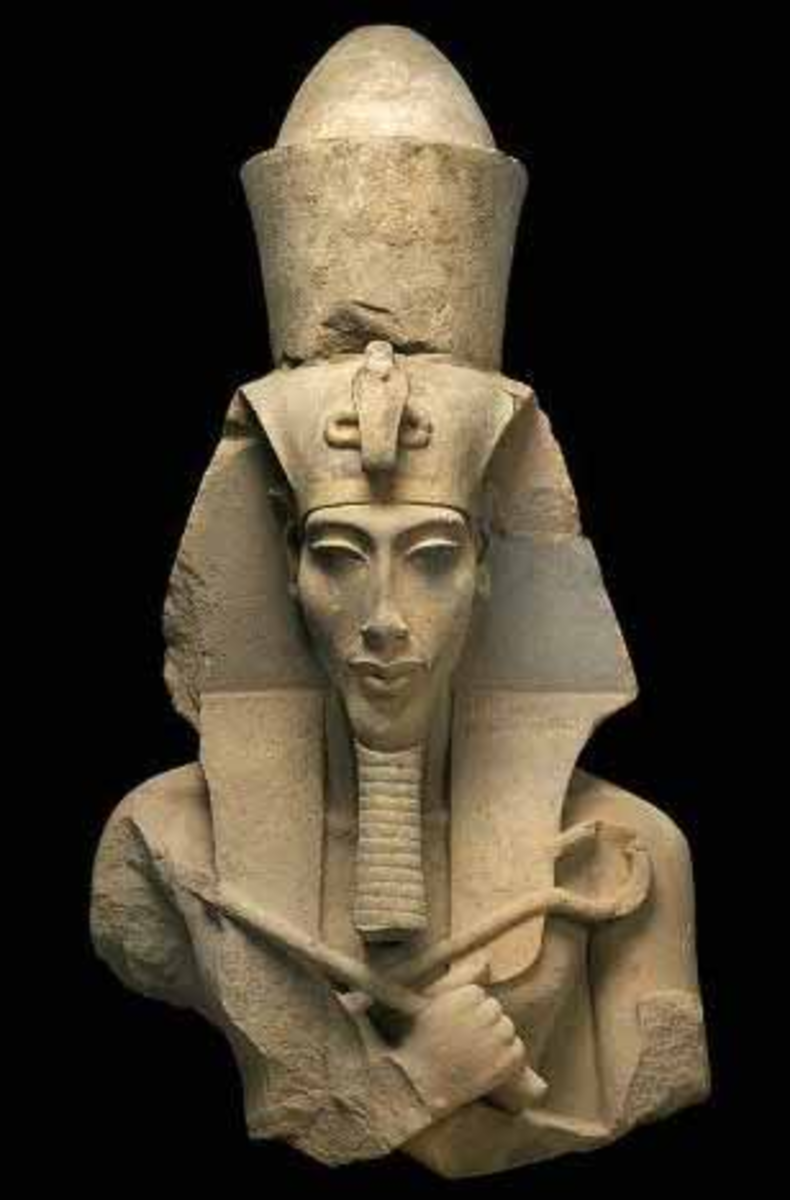

She also encouraged a patriotic image of herself, assuming the title, “Queen Cleopatra, the Goddess, the Younger, Father-loving and Fatherland-loving.” The name Cleopatra itself means, “a glory to her father” (Wyke 202). Like many Ptolemaic queens before her, beginning with Arsinoe II Philadelphos, Cleopatra was worshipped as a goddess during her lifetime, associated with both the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Greek goddess Aphrodite. She and Caesarion were frequently depicted as Isis and Horace in Egyptian art, and many called Cleopatra “nea Isis” or “the new Isis” (Wyke 200).

After the battle of Actium, however, the Roman image of Cleopatra declined in what E.E. Rice called “one of the most terrible outbursts of hatred in history” (Wyke 197). The poetry of Virgil, Horace, and Propertius all portrays her negatively and does not even address her by name, instead choosing to call her “Aegyptia coniunx” (the Egyptian wife), or merely “woman,” “queen,” or “that one” (Newman 231, Wyke 206). Her illustrious lineage goes unmentioned, except for her label as, “the one exceptional disgrace of a dynasty that claimed descent from the kings of Macedon” (Wyke 205).

Propertius wrote that Cleopatra was “the kind of woman who wears herself out in intercourse with her own slaves,” being immoral, perverse, and excessive (Wyke 207). Her marriage to Antony was not recognized as a true marriage by the Romans, who considered him to still be married to Octavia, and her marriage to Caesar was also denied, as it would mean recognizing Caesarion rather than Augustus as a claimant to the rule of Rome. When poets referred to her as “Aegyptia coiunx,” they really meant Egyptian whore, as an Egyptian wife was no wife at all.

For years before the battle of Actium, Egypt and Egyptians themselves had been portrayed negatively, with the Greek playwright Aeschylus painting them as barbaric hedonists (Wyke 210). Athenian sources in general are slanted against the Egyptians, referring to them as “crocodiles, beer-drinkers, and papyrus-eaters” (Wyke 210). This Athenian portrayal of the east as an uncivilized and inferior “other” was later adopted as a Roman attitude toward conquered lands, partly to justify Roman expansion (Wyke 210).

Athenian drama also casts powerful women in a negative light, and women are shown as having more power in more barbaric lands, in contrast to the orderly Athenian patriarchy (Wyke 213). Viewed through the Athenian lens, Egyptian customs of placing women in power seemed barbaric. According to Herodotus, Egypt was “for the most part the converse of those of all other men,” with the men staying at home and weaving while the women conducted trade (Wyke 213). Diodorus Siculus wrote that in Egypt, “the queen should receive greater power and respect than the king and that, among private individuals, the woman should be the master of the man, and in the dowry-contracts husbands should agree to obey the wife in all matters” (Wyke 213) The high level of female power in Egypt was exaggerated and used to portray Egyptians as barbarous. To the Greeks and Romans, the Egyptians must have seemed a backward society in the tradition of the mythical Amazons.

The association of the east with the powerful, untamed feminine may also have served to encourage and justify its conquest by the masculine order of the west (Wyke 215). Thus Octavian’s power struggle with Antony and Cleopatra becomes more than a dispute over territory and gains the additional meaning of what Maria Wyke calls “an heroic Caesar’s fight against tyranny, female dominance, and the perils of the orient” (Wyke 221).

It is largely the subversive, Roman view of Cleopatra and the east that has survived to the present day. William Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, the subject of many film adaptations, is largely the story of Marc Anotony’s seduction from the masculine order of Rome to the decadent femininity of the east, from Roman statesman to “strumpet’s fool” (Wyke 250). Worse than a strumpet, Enrico Guazzoni’s 1913 film Marcantonio e Cleopatra portrays the queen as an oversexed murderess who throws one of her slaves to crocodiles in a fit of jealous rage (Wyke 251).

This is hardly the positive, patriotic, and motherly image promoted by Cleopatra in life, but sadly for historical accuracy, it sells. It was used by Fox to advertise actress and early femme fatale Theda Bara in the 1910’s. Bara, Fox claimed, “had been born at an Egyptian oasis, in the shadow of the Sphinx, and had sucked the venom of serpents as an infant” (Wyke 268). She was a “reincarnation of Cleopatra,” a dangerous, exotic vamp (Wyke 268). Actresses portraying Cleopatra, from Claudette Colbert to Elizabeth Taylor, have dripped with glamour ever since, and the Cleopatra of popular culture is almost as much a fashion plate as she is a historical figure.

Portrayals of Cleopatra have changed greatly over the years, with her present day exotic image owing much to Roman propaganda and sensationalist film advertisements. This image overglamorizes Cleopatra and turns her into an exotic curiosity rather than the powerful, competent Egyptian queen she was. The Cleopatra that we find on the shelves at Wal-Mart between the sexy nurse and the she-devil around Halloween is not the Cleopatra that we could have found in Athens in 32 B.C.E.

Works Cited

Lightman, Marjorie, and Benjamin Lightman. Biographical Dictionary of Ancient Greek and Roman Women: Notable Women From Sappho to Helena. New York, 2000. 66-69.

Newman, Frances S., ed. "Cleopatra VII." The Ancient World. Salem Press, Inc., 2004. 229-233.

Rowlandson, Jane, ed. Women and Society in Greek and Roman Egypt: A Sourcebook. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 229-233.

Wyke, Maria. The Roman Mistress. Oxford University Press, 2002. 195-320.