Extending Legal Rights to Social Robots - A Though Experiment

When debating legal rights, especially those of robots, it is often easy to misjudge the scope of the topic. How does the law distinguish between what is known as a “social robot”, and a household appliance? To better understand if laws should be made to include the rights of robots and to what extent these laws will do so, it must first be determined what exactly a “social robot” is, and what laws should/can apply to it. The scope of the discussion is limited only to “social robots”, and the rights being debated are those the “second-order” type. Second-order rights extend beyond that of basic property rights, and ensure the protection of all entities under their jurisdiction. One discussion of social robots and the rights which should be bestowed upon them is in the form of an article by Kate Darling. Darling is a researcher at MIT, and author of “Extending Legal Rights to Social Robots”. In her paper, Darling discusses the definition of a social robot, second-order rights, and the likeliness that people in society will demand to extend legal rights to robots. Darling also discusses and proposes some guidelines regarding whether those rights should even be considered, and eventually granted. While Darling’s discussion of social robots and their interactions with humans is comprehensive, a discussion of the ethical implications of extending legal protection to robots is not covered. The idea that robots should be granted rights of any kind under law not only affects the robots themselves, but also the engineers designing and producing them, as well as the businesses making them. Some ethical implications regarding engineers which need to be addressed are the concepts of liability, engineering standards and the standard of care, privacy, respect for nature, and the rights approach. All of these topics will be discussed in detail later. Other ethical implications which do not concern engineers, but rather society as a whole are that of the Golden Rule, and whether it is wrong to harm someone else or to harm something for which someone else has feelings. Part of the reason ethical issues are so tantalizing and challenging is because they are subjective in nature. Creating and extending legal rights, however, must be objective. Applying legal rights to robots would be a matter which would need to be scoped out, meaning it would need to be clear what rights are being extended. To many, the rights may seem too little, and to others too much. The discussion of robot rights should cover both the objective and subjective nature of the topic, with the objective being the legal rights to be extended, and the subjective being what exactly defines a social robot.

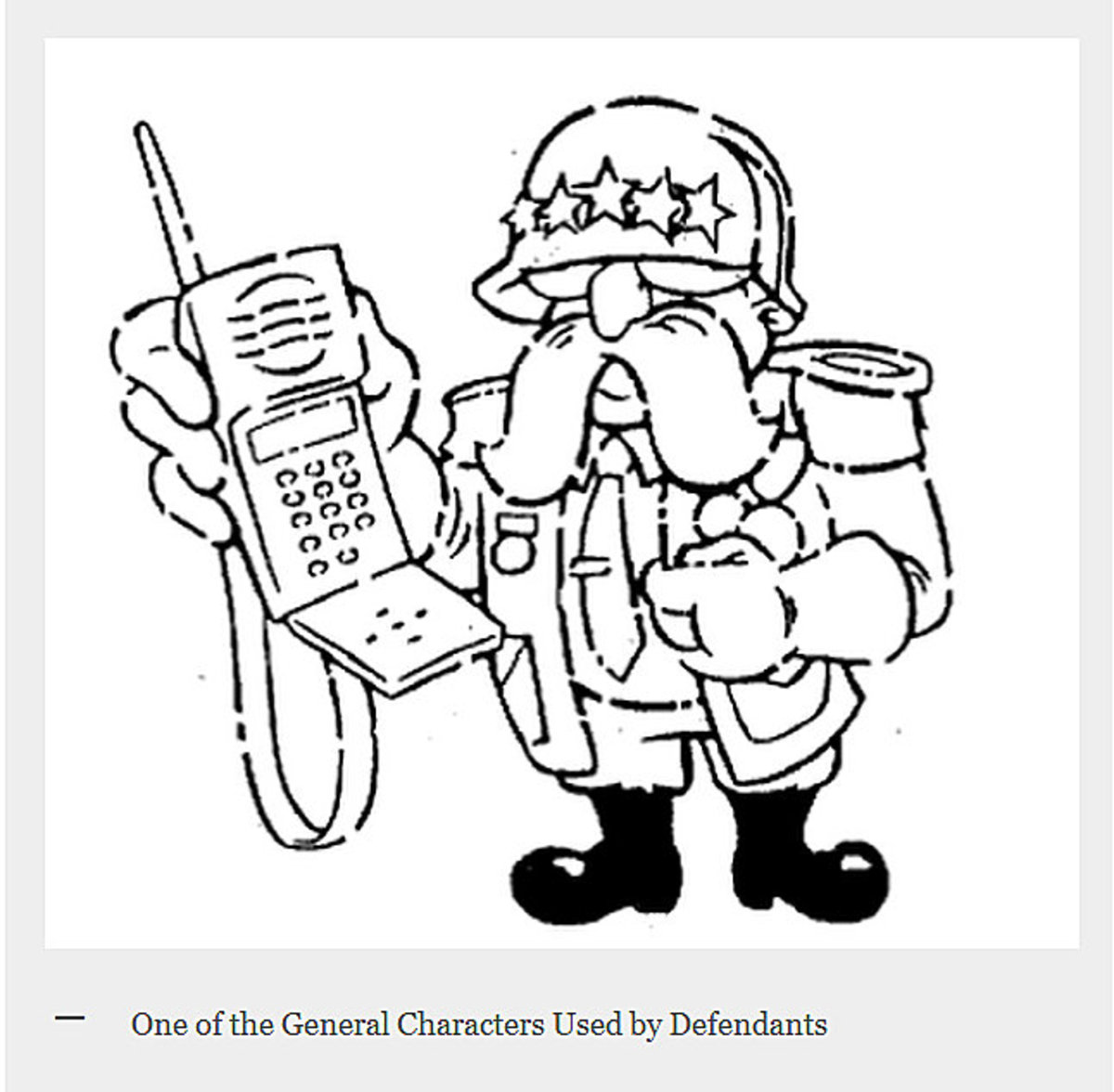

Kate Darling’s paper discusses in detail both the reason why society might push for social robots to have rights, and what rights might be the first to be suggested. Throughout her paper, Kate attempts to define certain legal parameters, as well as suggest a possible course of action. Kate answers the question of how to distinguish between social robots and appliances when she described the difference between a toaster, and a toy dinosaur. Kate stated “both are man-made objects that can be purchased on Amazon and used as we please. Yet there is a difference in how we perceive these two artifacts. While toasters are designed to make toast, social robots are designed to act as our companions.” This is truly the crux of the debate. “Robots” are perceived by people in a variety of ways. Kate describes it as a spectrum, ranging from electronic calculators, to the most social of robots containing human-like flesh and being capable of intelligent thinking. Whenever someone mentions robots, a different image appears in each listener’s mind. For robots to be granted rights, that image must be made homogeneous throughout the legislation, and throughout discussion. Kate attempts to lay out rules for which robots are to be considered when she says “A social robot is a physically embodied, autonomous agent that communicates and interacts with humans on an emotional level. For the purposes of this Article, it is important to distinguish social robots from inanimate computers, as well as from industrial or service robots that are not designed to elicit human feelings and mimic social cues. Social robots also follow social behavior patterns, have various “states of mind”, and adapt to what they learn through their interactions.” She later gives some example of social robots which include “interactive robotic toys like Hasbro’s Baby Alive My Real Babies; household companions such as Sony’s AIBO dog” and many more. The difference between standard electronic devices and social robots also extends beyond just the functionality of the robot, it also includes how they make us feel. Kate goes on later to say “Humans form attachments to social robots that go well beyond our attachments to non-robotic objects.” The interaction between humans and robots is best described as humans having an “inherent inclination to anthropomorphize objects that act autonomously”. When objects act as if they are alive, even if we know they are not, we tend to interact with them, and project human or even animal feelings onto them. It is with this projection that humans can get attached, or even socially or emotionally invested in a robot, even if they know it is not living. Kate gave an example of how even the most rugged of humans (military colonels) can anthropomorphize with robots. Kate says “For example, when the United States military began testing a robot that defused landmines by stepping on them, the colonel in command called off the exercise. The robot was modeled after a stick insect with six legs. Every time it stepped on a mine, it lost one of its legs and continued on the remaining ones. According to Garreau (2007), ‘[t]he colonel just could not stand the pathos of watching the burned, scarred and crippled machine drag itself forward on its last leg. This test, he charged, was inhumane.’ ” Human interaction with robots extends far beyond using them as simple, or even complex tools. Humans anthropomorphize with robots, and even befriend them. This interaction has led to a movement to grant such robots rights beyond the already existing property rights.

The rights which Kate Darling, and others who argue for robot rights tend to agree upon are what are known as “second-order” rights. Second order rights are those which are extended “to non-human entities, such as animals and corporations.” She describes that as of now, robots do not have rights. She discusses that robots might never actually gain rights because many people believe they are property. While Kate describes why society might want robots to have rights, she leaves out how robot rights activists should go about attaining those rights. I believe that the push for robot rights will follow the same course of events as that of human beings at various times throughout history. Women in Western societies leading up to the 20th century, and even women today in other countries face adversity in declaring that they are not property, and should be treated as humans. Africans in both Africa, and the Americas faced similar problems in being considered property. All of these peoples faced the issue of being considered property, yet, still managed to attain the same rights as their “owners”. The question posed by Kate is whether robots could do the same. The counter argument to this is that robots are not humans, and cannot be entitled to human rights. Similar to a robot is a corporation, which is not a human either. Yet, corporations are extended (under law) many of the same rights humans are. The legal implication of this is that it sets a precedent that an entity does not need to be human to have rights. Another argument which tries to prevent robots from attaining rights is the notion that robots are not intelligent. Kate counters this argument when she says (in another paper of hers) “Indeed, the argument has been made that humans are not intelligent, and this is intended seriously, not as irony or sarcasm. The people who make this argument contend that the brain is a very complex computing machine that is responding in a very sophisticated, but mechanical, manner to environmental stimuli. If robots can only simulate intelligence, such people would argue, then so do we – at which point my professor’s point makes all the more sense: it makes no difference if we are intelligent, or whether we just seem so.” The very fundamental argument for robots having rights is that they do not need to be human, or even act human to be valuable, or legally protected. Corporations are not human (and rarely act human), however, they are granted rights under law.

The ethical implications of giving rights to social-robots extend far beyond societies interaction with these robots. What must also be considered is the responsibility of the company, and the engineers who develop such robots. Engineers who develop such robots often do so with the purpose of such a robot being clear, and well defined beforehand. If robots are to be extended rights, and maybe be considered citizens, is the engineer liable for anything that robot does? Is the company which produces that robot ultimately responsible for any crime or malfunction that robot does or has. “Engineering Ethics” describes liability when it states that entities can cause harm intentionally, recklessly, or negligently. Regarding robots, would the harm a robot does be considered intentional by the software engineer since they programmed the robot (even if it was not explicitly) to behave that way? Or would they be negligent since they designed a product that had the ability to act in a malicious way? To help protect engineers, the four conditions mentioned in the book must be considered. First, engineers must make sure that they conform to any standards of conduct. They must also make sure that if accused, they conform to the standards. They must also work to ensure that their conduct must be abstracted from the source of harm. Finally, engineers should ensure that no loss or damage to the interests of another can result from their robot. With these in mind, it is increasingly apparent that these conditions cannot be met and still have a functional social robot. Another ethical issue is that of engineering standards regarding robots, and the standard of care. The standard of care is described by the book as being not restricted to regulatory standards. Assuming legal rights are to be extended to social robots only, if robots are to be extended rights similar to those of humans, there must be a standard by which companies produce such robots, so as to allow them to be classified as “social robots”. One ethical issue is how engineers will be able to determine such a subjective property as whether the robot is considered social. The process by which a robot is social must involve some sort of information sharing, which leads into the issue of privacy. How will companies be restricted to not allow their robots to gather vital data about customers? If a robot reports data to its company, is the company then in violation of that human’s privacy? The book describes this issue when it states “respecting the moral agency of individuals also requires that their political rights be respected, including the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.” This raises the question of whether social robots will be held accountable for information in a court of law. If robots are to become man’s new best friend, how will it affect the environment? Engineers are responsible for adhering to the many laws and regulations which are put in place to help prevent pollution. The book describes environmental laws and their limitations when it says “most environmental laws are directed toward producing a cleaner environment.” Extending what the book has put in place, if robots are to be granted rights, they should be designed to adhere to these laws. Engineers too will be faced with the problems of making robots which are “green”. Other ethical implications which do not concern engineers, but rather society as a whole are that of the golden rule, and whether it is wrong to harm someone else or to harm something for which someone else has feelings. The golden rule states that one should do onto others what they would want done to them. The push by individuals such as Kate Darling to grant rights to social robots hinges on the fact that individuals do not want harm to come to their companions. Because what is moral does not always match up with what is legal, it is difficult to say whether something should be illegal if it does not apply to an objective subject matter. Robots, specifically social robots, are not of one variety. Rather, they exist on a spectrum ranging from intelligent to basic appliances.

Social robots are increasingly becoming a normality in society. Many individuals interact with robots (both physical and non-physical) every day. Today, robots are simply there to aid human beings in performing tasks. Tomorrow, however, robots may be seen by many as being companions. When such a day comes, laws and legislation will be needed to determine whether such robots should be extended similar rights to humans. These robots cannot (for obvious reasons) be considered equal to humans in the eyes of the law, but they can however enjoy the same rights as other non-human entities such as corporations. In her paper, Kate Darling showed that social robots are already present in society, and are already having an impact on humans. She alluded to a time when these robots will be a major part of our everyday life, and that they will need protection of sorts greater than just property rights. The ethical implications of allowing social robots legal rights affect both the engineers who design them, as well as the society in which they exist. The engineers who design such social robots must be aware that they can be held responsible for the actions of that robot. They should also keep in mind that if legal rights are extended to those robots, they too must follow a standard of care and be sure not to induce harm of any sort, intentionally, recklessly, or negligently. The society in which social robots live with rights must also consider the ethical implications of the presence of robots. They must follow the golden rule, and ensure that the robots are treated so as to not cause emotional harm to the humans with which they interact. Social robots are certainly a technology which is increasingly becoming a part of our culture. The legal rights of such robots, however, are still far from being comprehensive.