- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

Conquest - 2: Farewell to Legend - Harold's Entombment at Waltham, Fact or Myth?

How well does the story stand up to close scrutiny? Read on and make your own mind up...

Many have challenged the story...

of King Harold's entombment at Waltham. Whilst even more have agreed with the tradition, some assert he may have been laid to rest at Bosham. He did own both, and on the face of it either would have been possible. Bosham is closer - westward around the coast from Hastings - in what is now West Sussex.

Few historians who tackled the question have given their findings the authority applied by William Winters FRHS. Winters wrote an essay in 1892 titled 'WAS KING HAROLD BURIED AT WALTHAM?' when nearing the end of a fore-shortened productive life spent diligently scrutinising historical documents, not only on this particular subject but also on history connected with the town.

William Winters was born in 1834 at Walkern. At the age of four he was brought by his mother to Waltham Abbey, who had found a new husband in the small town. His new step-father was a labourer, so life was not easy. Schooling was largely at Paradise Row Sunday School, and brief at that! He was working by the age of eight at the local silk mill. However, he did learn to read and write, which would stand him in good stead in later years. He was at the mill for up to four years when it closed down. He soon found a new job and by the age of fifteen he was on his fourth job when most of us would still have been at school. Times were hard and he could only find work tending cattle on the marshes. 'My days were long, my wages small - nor did I have a day's holiday or rest, Sunday or weekday', he wrote later. Having endured this for five years he was given work at the Royal Gun-powder Factory (RGPF), its wares in higher demand from the mid-1850s (Crimea). The RGPF's quick growth gave him security and a fair wage for many a year afterward.

In 1856 William began going with his mother to the Baptist Chapel where he first met Mary Maynard. They married two years later and he bought her grandfather's bookshop and stationery business at Lychgate House, opposite the south wall of the church yard.

He was elected clerk and then deacon of the chapel, developing an earnest interest in the Bible. He set himself the task of reading the New Testament in Ancient Greek and began learning the language. On his successful completion of the task he made up his mind to study the Old Testament in Hebrew. He also read books on English Grammar and the English poets, making good a curtailed education by collecting and reading books by the hundred. On his death his personal library was said to weigh about five [Imperial] tons. He was becoming known as a man of letters, and the basis of a wide-ranging writing career was being built.

As his book-selling business thrived Winters left the RGPF in 1865, before the Zulu War began. John Maynard, as close relative of his wife's wrote a history of the town, the first since 1735 and the book sold well, its popularity inspiring Winters to the prospect of a writing career for himself.

In 1867 he took a post as reader at the British Museum, marvelling at the books it held, and those valuable documents of the Public Record Office he had no access to. Until 1872 he worked largely as a records agent for other authors but began sending contributions to the 'Antiquary Notes and Queries' and other academic journals of the time. A series of articles on 'Celebrated Women of Essex' followed for the county newspaper and was followed by another on 'Celebrated Men of the Local Neighbourhood for the 'Waltham and Cheshunt Telegraph' under the pen-name Bibliopola (Book-seller in Latin).

The decade saw his writing flourish. 1870 witnessed a 'Visitor's Handbook to Waltham Abbey', followed by guides to Barnet and Cheshunt for his publisher, 'The Telegraph', who had local editions. Some historical studies appeared on the life of King Harold, on John Foxe the martyrologist and a history of the Lady Chapel printed on its completed restoration by William Burges.

Some religious studies such as on the Wesleys' music were written as well as the authorship of 'Pilgrim's Progress'. In all the titles - historical or religious - there are two common threads. Firstly there is the wish to find the truth of the matter and secondly is a sharp eye for presentation and timing. There was now an audience who knew what themes they wanted to follow, and he fulfilled their needs. This was why his book-selling business thrived.

He was an amateur artist as well as a gifted writer and sketched local views. His membership of the Anastatic Drawing Society shows an early wish to illustrate his books economically. At the time copper plates and woodcuts called for serious financial commitment, and photographic prints were still an area for craftsmen. He also joined the Royal Historical Society (RHS) and was honoured by election as a Fellow of the society.

By the end of the 1870s he had written about the library of the Abbey of Waltham, transcribed and indexed the parish registers and made use of his working knowledge by his time at the RGPF for Captain F.E. Smith's 'Handbook of the Manufacture and Proof of Gunpowder' (no Official Secrets Act at this time existed to curtail freelance activity in journalism). Histories of the town of Waltham Abbey and Nazeing were compiled from old documents at the Public Record Office. A collection of hymns was written for the chapel's jubilee, and he contributed to the 'Christian Standard' and other religious periodicals. Several poems also came from his pen. Amid this flurry of activity he was elected pastor of Ebenezer Chapel in July, 1876.

Writing feverishly into the next decade, a study of the clergy after the Dissolution was followed closely by 'Notes on the Pilgrim Fathers of Nazeing', a history of the Eleanor Cross (around the time of its completed restoration), a history of the town and a book of the parish register anecdotes. He may have been reminded of his own boyhood when he wrote 'Boy Life, or Notices of the Early Struggles of Great Men' and 'Centenary Memorials of the Royal Gun-powder Factory'. Regular submissions were still being made to religious periodicals, writing a series of lives of the hymn writers for 'Cheering Words', and regular chapel meeting reports were sent to the 'Earthen Vessel & Gospel Herald'. Before long he was editing both journals and maintained this flow of work until his final days.

A foot complaint manifested itself in 1890 and he was left sometimes unable to walk. He would rally, but relapsed in 1892 and his health deteriorated quickly. With mortality creeping up on him his ministry gained pace. Sermons delivered that year were seen as 'savoury' and a 'special time of spiritual festing'. New converts swelled the congregation but the flow of writing dried to a trickle. On top of editing 'Earthen Vessel' he wrote a last 'Sunday School Hymnal' in 1892. 'The Burial of Harold at Waltham' was also completed in this year, possibly when he was thinking of his own demise.

He died in 1893 at the relatively early age of fifty-eight, when many at this time still had a decade or so left in them. He left three manuscript histories of the district, all of which were published by the Waltham Abbey Historical Society.

Of Harold's burial at Waltham Abbey Winters wrote that many historians disagreed - in the 19th Century - with the story that the king was buried there, discarding testimony from William of Malmesbury amongst others. These writers insisted he was able to leave the field - missing left eye notwithstanding - and lived out his days as a hermit monk in or near Chester. This myth was quoted by the historians Knighton and Brompton.

Harold established a college at Waltham, supervised by Dean Wulfwin with canons who oversaw the teaching. After the Conquest the Normans established an abbey around the church and college. When Henry dissolved the monasteries his men were in the process of demolishing the abbey church when the townsfolk protested to Henry that they would have nowhere to worship. So the altar was moved west and a new end wall was built, leaving Harold's tomb out in the open. This is how you see it now.

The Burial of Harold at Waltham...

Fact or fiction? The legend and the argument.

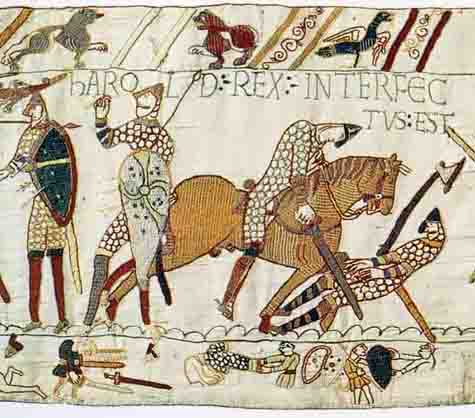

Through his chaplain William asserted his unwillingness to allow Gytha, the mother of the 'usurper' Harold, to take his badly mutilated corpse to be 'dressed' and made ready for burial.

She had, after all lost nearly all her sons in bloodshed between AD1052 and AD1066 (her eldest Svein was slain by robbers near Constantinople on his return from the Holy Land to atone for his many sins, four others - Tostig, Leofwin, Gyrth and Harold - killed within the past three weeks or so). Only Wulfnoth remained, and she had not seen him since he was taken with Svein's son Hakon by Robert of Lumiege as hostages to Normandy in AD1051. Wulfnoth would remain in captivity in Normandy until after William's death in AD1087, only then coming back to England to be held under house arrest until he too died in old age in the reign of Henry 'Beauclerk', the 'Conqueror's youngest son. Gytha offered the duke Harold's weight in gold - she did have that much wealth - but her offer was refused. The duke joked that Harold would be buried on the shingle beach so that he could look out for Norman ships.

There is a story that Gyrth, Harold's next younger brother after Tostig, escaped and was represented in conversation with Henry II, speaking mysteriously about Harold and telling him his brother's corpse was not at Waltham. More contemporary chroniclers stayed silent on the matter, not wishing to 'rattle bones'. Their king was dead, they knew, and did not care to dwell on the finer points of their sorrow.

Nothing is mentioned of Harold's burial in the Saxon Chronicle. The English biographer of Eadward left Harold out of the narration, as if he had never reigned. This was possibly at the wishes of Church seniors who wanted no further trouble. In the Vita Haroldi he is said to have been taken alive - from the battlefield by a Saracen woman who hid him at Winchester. He is next said to have gone to Jerusalem, coming back to England to lead the life of hard penitence - for what? It is at best an unreliable account, written perhaps to show Harold had not been killed or interred at Waltham. Was it written for propaganda purposes?

According to William of Malmesbury Duke William allowed Gytha to take her son's corpse, but Pictavensis told of the duke having Harold buried on the foreshore, 'Let him guard the coast which he so madly occupied', the duke is to have said, turning down Gytha's gold. However William of Malmesbury and the minstrel Wace were considered independent witnesses, and the most likely version is that William did have Harold interred on the foreshore but was moved by Gytha's plea. He may well have been indisposed to clemency towards the man he considered a 'usurper' and his kind, but milder counsel would finally win through.

The abbot of Hyde and twelve Brothers searched fruitlessly for Harold's corpse. Osgod and Ailric, two of the Waltham canons who went to the south coast with Harold were likewise unlucky. Eadgytha 'Svannes-hals' (Swan-neck) found him amongst the unburied corpses by marks on his body only she and his mother knew. He was taken to Waltham and interred at the east end of the Choir - destroyed on the orders of Henry VIII before the perpetrators realised the townsfolk would have nowhere else to worship - with honour and respect, Norman men-at-arms even helping in the requiem. Robert of Gloucester, a monk who lived at the time of the battle of Evesham, wrote (in Middle English) of Harold's burial:

"Harolds moder vor hyr sone wel gerne him bysgote,

By messagers, and largely she hym bed of her thynge,

To grante hyre sone body anerthe vor to bringe,

Wyllam send hyr vayre yuon wytboate enyhynge warnore,

So that yt was born hyre with gret honour y bore,

To the hous of Waltham, & ybrogt anerthe there,

In the holy rode Chyrche, that be let hym sulfrere"

The historian Speed was at one with this account. The Waltham manuscript De inventione Sanctae Crucis has a detailed account of the Waltham canons , of how they watched the way the fighting went and then sought out Harold's mutilated corpse. Wace told: 'King Harold was carried and buried at Varham (Waltham), but I know not who buried him'.

One historian, A le Prevost picked up on the way Harold was interred, on the manner described by William of Poitiers and by Orderic Vitalis. He noted also that Duke William refused Gytha permission to take her son's corpse, but granted William Malet the favour to do the same. Orderic Vitalis wrote of the corpse being handed over. M. le Prevost used the phrase penned by Orderic Vitalis that he allowed William Malet's request because he saw no particular motive as neither knew the other. The editor of the Wace chronicle believed the boardly held tradition of Malet being uncle to Harold's queen Aelfgifu and he was also kindred to Duke William through his marriage to Hesilia Crespin. Benoit de St. more wrote confirming William of Poitiers belief that Harold's corpse was given to William Malet 'by his earnest plea with remission to bury it where he wished'.

The date of the Wace chronicle is given on good authority as being around AD1200. Another thirteenth century poet wrote:

'Through the prayer of his mother,

The body was carried on a bier,

At Waltham it is placed in a tomb

For he was the founder of the house'.

(Inaccuracy is found in many mediaeval writers' works; Godwin Wulfnothson was the founder of which was the most famous scion).

An early (translated) document written by Peter of Ickham went:

'King Harold, when earl, built the Church of Saint Cross at Waltham whither his body was borne after the battle [at Caldbec Hill, known to Norman writers as 'Sanguelac/Senlac'] to his mother's prayer'

Roger Wendover, known widely as the author of 'The Flowers of History' flourished in the reign of King John. He affirmed the story of Gytha asking for her son's corpse and that William had it sent without the payment offered. A chronicle penned by Fabyan towards the end of the fifteenth century wrote:

'Thus when Harolde hadde ruled the land... he was slayne and was buryed at the monastery of the Holy Cross of Waltham which he before had founded and sette therein channons (sic) and gave unto them fayre possessions. And here endeth for a time ye blod of Saxons'.

Quoting from an old work the historian Strutt noted tersely:

'Harold lies buried at Waltham'.

Dr. T Fuller went further:

'Let not therefore the village of Harold on the north side of the Ouse (Cambridgeshire, i.e., Harelswood or Harewood according to some groundless belief) contest with Waltham for the king's interment'.

The early biographer and monk of (the later abbey of) Waltham 'is driven' according to Freeman, 'to a very lame device indeed. He had to reconcile his beloved fiction of Harold's escape with the tradition of his abbey, wgich boasted of Harold's tomb. He is therefore driven to suppose that Eadgytha (Swan-neck) found, and that the chapter buried, a wrong, an intruding suppositious carcase, which down to his own time had usurped the sepulchral honours of the last Saxon kings. Now this kind of stuff is abominable [and so is the misuse of English, my words]. It is neither history, nor romance, nor criticism, nor anything else, but simply a cock-and-bull story of the poorest kind'. He went on to pull apart a theory put forward by (his) detractors of the Waltham interment camp in 'De inventione' of Harold's burial in East Anglia, saying that Osgod Knoppe, Allric and Eadgytha were mistaken in identidying the man who was close to them for many years. The rhetoric goes on to state, 'Harold was not an acknowledged saint, whose burial place would be a profitable place of pilgrimage. In the days of the Conquest any attempt of the kind would have been put down... When the tomb of Waltheof at Croyland became the scene of miracle and pilgrimage the Conqueror acted as vigorously as the more recent French king:

'"De par le Roi, defense a Dieu

De faire miracle en ce lieu"

An imaginary tomb of Harold could only have been set up from motives strongly tinged with political feeling, which (in turn) would have once kindled the wrath of the Norman government'

(Mr Freeman's strong opinions were obviously not widely held, to judge by Mr Winter's other sources). It is possible during the various alterations that took place in the abbey around the tomb between the reigns of William I and Henry II Harold's remains may have been translated from the original burial site. The writer of 'De Inventione' maintained Harolld was interred first near the high altar. Dr Fuller stated Harold's body lay near the foundations of the Earl of Carlisle's fountain in his garden, then probably at the end of the choir, or more likely an eastern chapel beyond:

'There is still preserved in the church a coffin-shaped stone of very early date. On its centre is a cross in relief, almost the full length and width of the slab which measures six feet nine inches in length, thirteen inches wide at the base and much wider at the shoulder. It is not early enough for Harold [not was Harold as tall as that, AL] , although some might suppose it to have been the one described by Dr. Fuller. The stone which D. Fuller maintained was in his house - the Vicarage, north of the church tower - a purporting to be a part of Harold's tomb, is in the north aisle of the abbey church, put there by the late Mr. Robert Clark. Thought to have been part of the Earl of Carlisle's fountain, this piece of ironstone is not linked Harold's tomb. It would have been an ornamental element of the earl's fountain but Mr. Fuller - a local resident - knew its history well enough not to assume it was carved for his wealthy patron's garden centrepiece'.

John Farmer, who lived in the 18th Century said of the fragment,

'I have it now [1735] in my house. It is a curious face or bust of grey marble, which by tradition always was, and is to this day, esteemed to be part of King Harold's tomb'.

The author of the History of Waltham Abbey added,

'It is without dispute that he [Harold] was buried in [what was then] the garden, under a a leaden fountain, where now there is a bowling green which formerly belonged to the Earl of Carlisle'.

Coming to where Harold's remains were buried, Taylor said in his poem 'Eve of the Conquest',

'In Waltham Abbey on St Agnes' Eve

A stately corpse lay stretched upon a bier.

The arms were crossed upon the breast, the face,

Uncover'd by the taper's trembling light,

Showed dimly the pale majesty severe

Of him whom death, and not the Norman Duke

Had conquered; him the noblest and the last*

Of Saxon kings; save one the noblest he;

The last of all' [Edinburgh Review, Vol. 89].

*Eadgar 'the aetheling' was made king subsequent to Harold's death but not crowned. Nevertheless Eadgar was the last of the English/Wessex line.

History and tradition dictate the location of Harold's burial being about a hundred and twenty feet (forty yards) from the current east end of Waltham Church (the place of Sepulture of ecclesiastics and men of high standing in the Middle Ages) and near the graves of J Jessop Esquire and Colonel Edenborough. All that part of the churchyard where the old choir of Harold's original church was situated, known as the 'new ground' was plainly used as a garden by the Earl of Carlisle and sir Edward Denny after the fall of the central tower in the reign of Philip and Mary**. This additional part of the churchyard was originally used for interments early in the 19th Century with the permission of Sir William Wake, Lord of the Manor of Waltham Holy Cross.

** This was Mary Tudor who was secretly married for a short time until her death to King Philip of Spain.

Nothing remains of the tomb beyond the fragment on Robert Smith's marble tomb in the north aisle of the abbey church. The inscription on Harold's tomb (in Latin) is thought to have read:

'Harold infelix' - unfaithful Harold, referring to his having reneged on his AD1064 oath to William.

'A fierce foe thee slew, thou a king, he a king to be,

Both peers, peerless, both feared, and fearless;

That sad day was mixed by Firmin and Calixt;

The one helped thee vanquish, the other made thee languish,

Both now for thee pray, and they requiem say,

So let good men all to God for thee call'.

By the communion rails within the church is a stone which bears the following inscription:

'hic Haroldi; in Coenobio

Carnis Resurrectionem.

Expectat Jacobus Raphael Gallus

Demum Scotus demum Anglus,

Denique nihil,

Anno aetat 70

Obit Mar 30 Anno 1686'

[James Raphael was buried on April 1st, 1686, Parish Register]

Early in the 17th Century one of the windows in the north aisle of the church bore a portrait of Harold.

© 2012 Alan R Lancaster