Feminism in Ancient India

You may judge a nation’s rank in the scale of civilization from the way they treat their women.

— Thomas Babington MacaulayThe situation of women has alternately traversed through oppression and liberation; but never has it been denied that the welfare of a society is critically dependant on how it accommodates its women. The movement for women’s emancipation has always been perceived as a Western initiative, beginning with the white woman’s activism for freedom and right to property and suffrage that gave rise to the first phase of the Feminist Movement. Furthermore, in the absence of patriarchs, who were increasingly being inducted into the army, women were forced to step out of their households and adopt a responsible, more “masculine” stance towards both the state and the home. Given that the major global events (such as the French and Industrial Revolutions), were taking place mostly in Europe and the West, the East was relegated to the status of the uncivilised, colonised victim.

Pre-independent India was hostile to the welfare of women; it was the English colonisers that helped rid society of ills like sati, child marriage, and lifelong widowhood.

This is the version of reality that Indian children grow up internalising. Despite the country’s constitutionalised secularism, the presence of Hinduism has often been strengthened in the minds of people with relation to the religion’s orthodoxy and its inimical attitude towards women. Practices like sati, stigmatised laws for widows, and an overall restrictive attitude towards women were predominantly seen as an aspect of Hinduism, propagated in particular by the puritanical Brahman caste. This synonymy between Brahmanical backwardness and the plight of Indian women has consolidated the idea that this country has never been very good to its women, and that it was only under the influence of Western education that women gained any semblance of emancipation.

Such histories completely tarnish India’s image and give credit to the West for an enterprise that is not unique to it. In saddening contrast to the present state of affairs in society, India’s past holds liberal values and ideals that would put the modern world to shame. It is not the West, not the demand for the right to vote that instigated freedom for women in the world. Women have enjoyed reverence, respect and freedom in this very soil where now rise in rape has torn all sense of security apart. The Vedic Age, circa 1500BC, was a time when men and women were seen as equal halves of a complete whole – in marriage, the wife was called the ardhangini, or the ‘other half’. The Mahabharata, which is recognised as one of the greatest representations of the Hindu culture, besides providing “sweeping visions of the cosmos and humanity” (Brown University on The Mahabharata), is in many ways testimony to the liberal mindset which prevailed in ancient Hindu India.

Draupadi's Polyandry

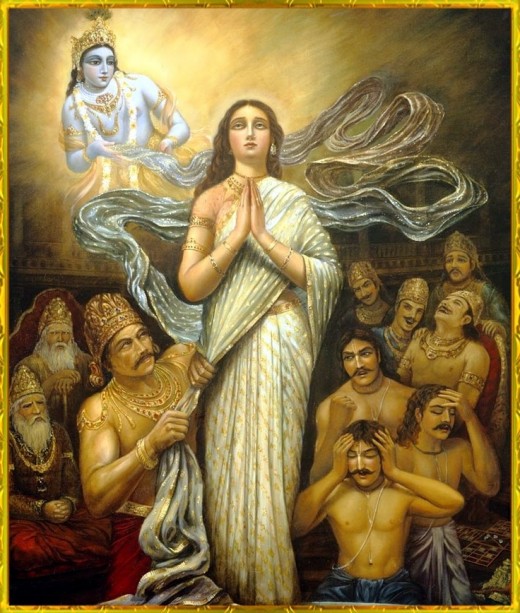

Draupadi’s polyandry with the five Pandava brothers in The Mahabharata is a story well known yet little scrutinised. Given the present impression that Hindutwa is generating towards Hinduism, it is difficult to place Draupadi’s narrative within India’s Brahmanical past. The story goes that when Arjun won the hand of the princess in her swayamvar and brought her home to his mother, the praying woman asked her son to share equally, whatever he had brought, amongst all his brothers, little realising what the entity in question was. As obeying a mother’s word was strict law in those times, Arjun had little choice but to comply with her command. The unrest caused by such an accident was calmed by the arrival of Lord Krishna, who reminded Kunti, the mother of Arjun, that Draupadi was destined to be wedded to five husbands and that there is nothing calamitously wrong with the situation. Feminist critics have severed all notions of freedom from this incident stating that Draupadi’s polyandry was a fated position and not a personal choice. But here we need to look beyond the question of choice into the larger atmosphere of liberal mindedness that allowed and accepted the possibility of a woman possessing five husbands. The oft cited episode of the dice game wherein Draupadi was pawned off by a losing Arjun and subsequently disrobed by Dushshasan is seen as a direct assault on the integrity of women. However, M. K. Dhavalikar, in his essay “Draupadi’s Garment”, reveals that the disrobing of Draupadi was not so much an act of dishonouring a woman as it was an act of stripping away the status of the dasi’s (slave) superiority. According to Dhavalikar’s study of The Mahabharata, uttarayas were upper garments that were worn by only and all members of the noble class, and it was this uttaraya that Dushshasan was attempting to take off the newly acquired slave, as a symbol of removing her nobility, thereby demeaning the rival Pandavas.

To look beyond the character of Draupadi, we may recall that Pandu, despite being the patriarch of the Pandavas, had not fathered any of his sons. Both Kunti and Madri (his wives) had called upon various devas or Lords to help them give birth to children in effect of a curse that was placed on their husband which claimed that he would die at the very moment of his copulation. Many feminist critics have looked upon all these episodes and events as representative of an unfavourable attitude towards women, as most of these appear to arise out of curses or disadvantages that had befallen them. But the fact still remains that women could partake in both polyandry and engage with multiple partners as was enjoyed by men, without contemporary society looking down upon the former as licentious or disgraceful. Also of significance is the story of King Dushyant and Shakuntala. The hermit’s daughter consented to amorous engagement with the king only after the latter promised her that their son would succeed him as king; and thus, this nation-region came to be known as the land of Bharat or Bharat-varsha, after the son of King Dushyant and Shakuntala.

The importance attached to the word of a woman and the arrival of a God to announce the unobjectionable nature of Draupadi’s marriage are only a few examples that shed light on the tolerant atmosphere that existed as far as equality between and respect for genders were concerned. Such events in the lives of women now, whether by choice, accident or punishment – will be condemned by society today. Such was not the case in Brahmanical Vedic India, and that is why Draupadi’s polyandry can exist with ease alongside characters like Kunti and Madri, all of whom are revered as noble and respectful women by followers of the Hindu faith. Once again, it is not India that was orthodox in its thinking, but the misinterpretation, misrepresentation and the mass following of a faulty understanding of the ancient texts that has given rise to the excessively intolerant atmosphere in the country today.

![5 Reasons Why Music is Important in any Society [Updated 2020] 5 Reasons Why Music is Important in any Society [Updated 2020]](https://images.saymedia-content.com/.image/t_share/MjA0NjIzNTE4NDE4MTUxMzUz/why-is-music-important.png)