- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Forcing the World to Listen: Ida Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells

Forcing the World to Listen: Ida Wells-Barnett

Though the Emancipation Proclamation freed all black slaves in the United States during the Civil War, it did nothing to ensure their safety from reprisals by defeated Confederates or persecution by hate-mongering racists. After the Civil War ended the lynching of black men shot up exponentially, with 235 confirmed cases in 1892 alone. Black men weren’t the only targets—black women were often so violently and horrifically treated by their white attackers that I can’t go into detail about it here. Black families lived in terror during this time—it seemed that there was no one brave enough to stand up to the hatred and terrorism against the black community.

And then someone started speaking up.

Born on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs Mississippi just a few months before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, Ida Wells was the eldest of seven children born to former slaves James and Elizabeth Wells. James had enrolled in Shaw University, but dropped out to support his family, earning a living as a carpenter and becoming involved with politics and equal rights for blacks, which had a great influence on Ida. When Ida was sixteen, she left her town to visit her grandmother. While she was gone, a yellow fever epidemic struck Holly Springs, killing both of her parents and her youngest brother.

Now that Ida and her surviving siblings were orphans, her relatives considered splitting them up and raising them apart, but Ida refused to hear of it. She insisted on keeping her family together, raising them herself with the assistance of her aunt Peggy, and supporting them all by becoming an elementary school teacher for black children. Still, it was difficult to make a living as a black woman teaching; the school system was strictly segregated, and while white women could make $80 a month teaching, Ida, a black woman, was paid only $30 for the same work. Ida resented the disparity, and became more interested in politics as a result.

In 1883, Ida took three of her siblings to live with their aunt in Memphis, Tennessee. While there, Ida was stunned to discover that black teachers in Tennessee were paid much more than in Mississippi, and she promptly moved her entire family to Memphis so she could teach. During summer vacations, Ida took classes at Fisk University, where she impressed people with her views on women’s rights, writing, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge.”

One year after moving to Memphis, Ida bought a first class ticket for the ladies’ private car on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Not long after she took her seat, a train conductor approached Ida and ordered her to move to the smoking car. Startled and angry, Ida refused, and the conductor and two male train engineers grabbed her and carried her off of the train. Beside herself with fury, Ida returned to Memphis and hired an African-American lawyer to sue the railroad for discrimination. The lawyer took her case, but he began accepting a payoff from the railroad to ruin her case. When Ida found out, she fired him and hired a white attorney who took her case to court and won.

Ida’s victory did not sit well with the railroad company and they appealed the verdict. The judge overturned the previous ruling, found in favor of the company and ordered Ida to pay the court costs. Throughout the ordeal, Ida wrote about her experience in articles for the weekly black church newspaper The Living Way, and her journalism soon earned her an editorial job offer from The Evening Star in Washington D.C. Ida then became editor and co-owner of the anti-segregationist paper Free Speech and Headlight, where she began documenting cases of lynching and other forms of terrorism committed against black people in the South.

In 1889, Ida’s friend Thomas Moss and two colleagues opened a successful grocery store catering to the black populace near Memphis. The grocery store operated directly across the street from a whites-only store, and in an area so segregated, you’d think that the local narrow-minded bigots would be happy that they had their own store and the black people had theirs, and never the two groups would meet. Sadly, it had the exact opposite effect; one day a mob of white men swelled up and attacked Moss’s store, as well as Moss and his employees. Somehow in the melee, three white men were shot and injured, so Moss and his employees were arrested and placed in jail to await trial. The whites were enraged by the wait, so they stormed the jail, dragged out Moss and his employees and hung them all.

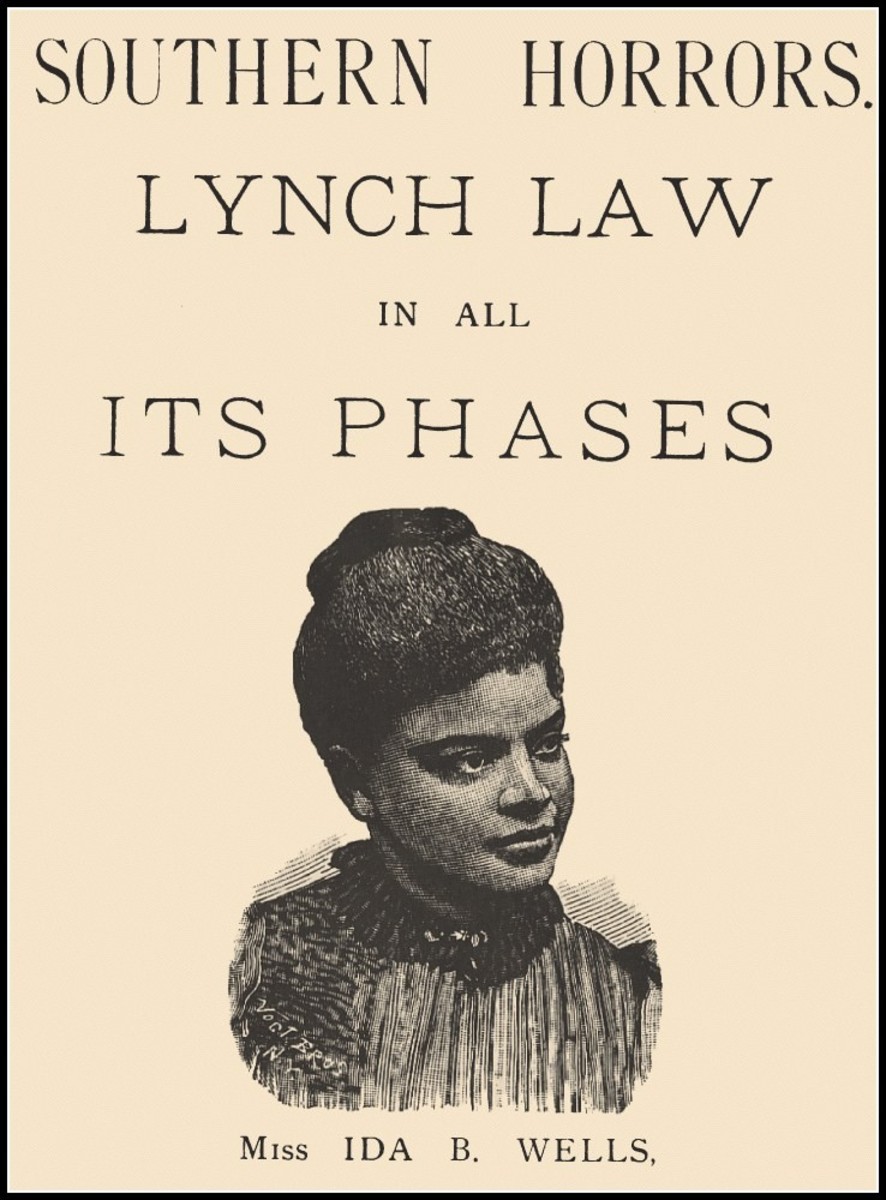

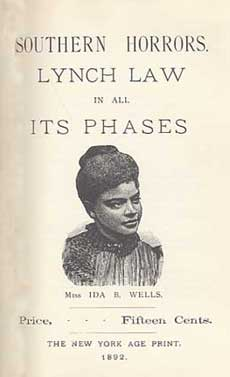

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases

Ida was horrified at the murder of her friend, but she refused to be cowed by fear. Instead, Ida wrote about the lynching, publishing the articles in her papers. She began a campaign of journalistic retribution not just against the men who had killed Moss, but against all lynchers in the South. She investigated the lynchings, describing the murders in gruesome detail, writing that the “lynching mob cuts off ears, toes, and fingers, strips off flesh, and distributes portions of the body as souvenirs among the crowd.” Ida refuted the details of “justified” hangings, and published the addresses of where the victims were murdered, along with the names of the white men who had killed them. “Brave men do not gather by thousands to torture and murder a single individual, so gagged and bound he cannot make even feeble resistance or defense,” Ida declared. In one article, she encouraged the black populace to abandon Memphis and find safer places to live, and about 6,000 African Americans heeded her advice. She then published all of her findings in the pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,revealed the evils of lynching to the world.

The lynchers were beside themselves with rage and disbelief—how dare a black woman stand up to them like that? They sent innumerable death threats against Ida, but she refused to waver, carrying a pistol with her at all times, writing, “They had made me an exile and threatened my life for hinting at the truth.” After her offices were destroyed by a white mob, the danger to her became too great and Ida moved to Chicago, where she resumed her crusade against lynching in her articles that were published across the nation and even in Europe. She worked with luminaries such as Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois to push change for black people. In 1893, she and Douglass organized a black boycott of the World's Columbian Exposition because the managers were depicting exhibits on African American life but refused to work with any actual African Americans in creating the scenes. Ida was also one of the founding members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW).

Ida also began a speaking tour, traveling across the United States and Europe speaking about lynchings and civil rights. Her speeches in Europe were extremely successful, and she wrote about them for the Republican newspaper The Daily Inter-Ocean, becoming the first black woman to write for a major newspaper in the United States. During this time Ida called out temperance movement leader Frances Willard on her declarations that black men were more naturally inclined to become addicted to alcohol and would then attack and rape white women as a result. Frances Willard countered Ida’s attack by claiming that Ida was only trying to get rich off of her anti-lynching tour. Willard’s insulting responses only bolstered Ida’s popularity in Great Britain.

In 1895, Ida, who had always been somewhat hesitant to become a wife, married her husband, assistant state attorney and Chicago Conservator newspaper editor Ferdinand Barnett, whom she had initially hired to help her with a libel lawsuit. Ida kept her last name along with her husband’s, becoming one of the first American women to do so (though she also went by the name “Ida B. Wells”.) They had four children, but Ida had a difficult time dividing her time between raising them, continuing her fight against racism and her increased work in the area of women’s suffrage, once saying, “I honestly believe I am the only woman in the United States who ever traveled throughout the country with a nursing baby to make political speeches.” Noting a decline in her work, suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony said that Ida seemed “distracted,” so Ida took a brief leave from her work to focus on her family.

In 1913, suffragism was in full swing, and new leader Alice Paul organized a march of suffragists through Washington D.C. on newly elected president Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration day. Determined to be a part of the historic event, Ida arrived in Washington D.C. with a delegation of 60 black suffragists. Alice Paul was shocked to see them; in order to get the Southern white suffragists to agree to the march, Alice Paul had promised them that no black women would be allowed in the parade with them. Ida stood her ground, refusing to be turned away, and Alice reluctantly allowed the black suffragists to march with them—just so long as they remained at the end. Ida agreed, but once the march began, she maneuvered her way to the front of the parade.

Once suffragism had been won and the 19th Amendment passed, Ida turned her attention to urban reform for African American people. She continued to fight for African Americans’ civil rights until her death from kidney failure on March 25, 1931. She died while working on her autobiography Crusade for Justice. Ida’s tombstone reads, “She told the truth in words so stirring she forced the world to listen.”

Ida Wells-Barnett works cited:

America’s Women, by Gail Collins

“Ida Wells-Barnett,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_B._Wells

“Ida B. Wells,” https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/civilrights/il2.htm

“Jim Crow Stories: Ida B. Wells,” http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_people_wells.html

“Barnett, Ida Wells,” http://www.blackpast.org/aah/barnett-ida-wells-1862-1931

“Ida Wells Quotes,” http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/i/ida_b_wells.html

“Top 25 Ida B. Wells Quotes,” http://www.azquotes.com/author/15488-Ida_B_Wells

Wells-Barnett House, Chicago IL