The Psychology of Why We Forget Things

The Evolution of Memory

If evolution could create perfect human beings, our memories would be capable of recalling every detail from our lives. Unfortunately, evolution is a steady, imperfect process in which living organisms adapt sequentially to immediate threats in their environment. Although a perfect memory would help us survive, the challenges we face haven't made it necessary. Squirrels, on the other hand, need to remember the location of vast quantities of nuts, and their memory has evolved to become greater than our own.

Despite this inevitable limit on human memory, evolution has at least determined the type of information that is most likely to be forgotten. Indeed, people who remember useful information are more likely to survive. Thus, the genetic traits that cause them to prioritize useful information pass to future generations. For example, humans have developed a tendency to forget things that happened to them a long time ago. This is because older information is less relevant to present concerns, making it a low priority. At the biochemical level, this can also occur through a process called neurogenesis.

Neurogenesis Makes Us Forget

Research published recently in Science found that neurogenesis, in which new neurons are created by the brain, can cause older memories to degrade or disappear. As neurogenesis occurs prolifically in younger brains and decreases as we get older, the researchers tested different ages of mice and other small mammals to see how long it would take them to forget that touching another cage would cause a small electric shock. They discovered that younger mice forgot substantially quicker than older mice. When they used drugs to slow neurogenesis in younger mice, their memories improved to the levels of older mice. The research could be applicable to humans as it would explain childhood amnesia (forgetting one's early childhood).

Although neurogenesis is likely to degrade long-term memory, and evolution is likely to have improved the retention of useful memories, this doesn't explain why we forget useful, short-term memories such as where we left our car keys a couple of hours ago. In fact, neurogenesis and evolution seem to argue against it. So, to address why we forget our car keys, we must draw on another piece of fascinating psychology research.

Short-Term Memory Loss

The cognitive psychologist, Gabriel Radvansky, performed a number of ground-breaking experiments to show why we forget information about objects we've recently interacted with.

In the first experiment, Radvansky created a virtual environment in which participants took an object from one room and deposited it in the next room. Once an object was picked up, it was no longer visible in the environment. Participants transferred a number of objects, and their memories were occasionally probed to see if they could remember the object they’d picked up in the previous room or the object they’d deposited in the present room. Radvansky found that we’re far less likely to remember objects we've put down. He concluded that dissociating oneself from an object causes the memory of it to become less accessible. Thus, just like when we can’t find our keys, the memory is there, but it's frustratingly difficult to access!

For some of the participants in Radvansky’s second experiment, there was no need to enter a second room before depositing the object. Participants covered the same distance in the virtual environment, but there was one large room instead of two small rooms. As before, once a participant picked up an object, it was no longer visible to them. Radvansky found that when participants didn't have to pass through a doorway, their memory for the object being carried or deposited was better than when a doorway was present.

Thus, Radvansky confirmed that two cognitive effects are in play. Passing through a doorway or putting down an object makes us more likely to forget about it. The two effects do not combine as much as one would expect. For example, putting an object down and passing through a doorway makes our memory marginally worse than doing one or the other. A possible explanation is that both effects utilize some of the same processes for making a memory inaccessible.

The Psychology of Memory

Given that we discard objects and pass through doorways on a regular basis, it's surprising that our memories are noticeably affected by doing so. However, if we recall that human memory has evolved to prioritize information that is most relevant to our present circumstances; an explanation is possible.

For example, entering a new room is more likely to make information about objects and events in the previous room less relevant to one's present concerns. Relatively speaking, staying in a single room makes everything in that room more relevant. This doesn't mean our minds have evolved to detect doors, rather, doorways are recognized as an event boundary between one environment and the next. It appears that changes in scenery set in motion an automatic updating process, akin to neurogenesis. New information about the current environment starts being collected, while information about the previous environment is made less accessible.

The reason we sometimes forget useful information, such as where to find keys, is because our brains do not consciously calculate its relevance. Instead, our brains automatically determine what's relevant via cognitive cues. These are events that have come to consistently mark the point at which information becomes less relevant. As discarding an object or changing scenery are common precursors to an object losing relevance; these events cause related memories to become less accessible. These cognitive cues are shaped by what is most beneficial to us. For example, objects currently in one’s possession could prove useful for future tasks (or to counter threats) whereas discarded objects are relatively useless in these potential scenarios. In other words, when faced with a crisis, it's better to remember what you have on you than what you don't!

Nature or Nurture?

These two cognitive effects on short-term memory may be the result of developmental learning, i.e. training our minds to recognize relevant aspects of our environment. However, there are a couple of reasons to think this isn't the case. First, these memory constraints are unconscious and automatic, meaning they're impossible to completely overcome. No matter how many times we forget the location of our keys, we keep losing them! Second, children display these effects more than adults, although further tests are needed to confirm this trend.

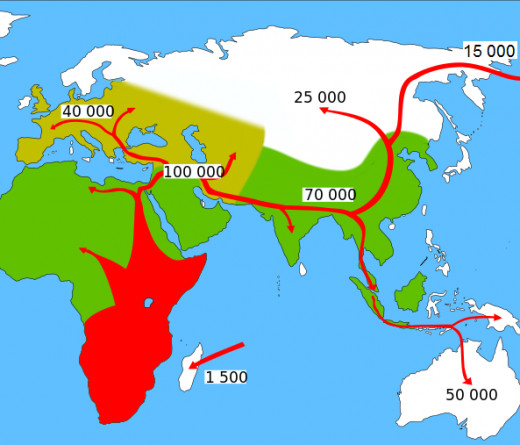

It appears likely that these two cognitive effects are as unavoidable and innate as neurogenesis. Indeed, the course of our evolution is characterized by our ability to adapt to new environments. When humankind left Africa to populate the world (see above), we were venturing into unknown lands with treacherous conditions, new predators, and new tools at our disposal. It would have been beneficial to forget irrelevant information about older environments.

Individuals who were adept at this propitious pattern of forgetfulness would have adapted better to the new way of life. Their survival may have left a lasting footprint on the brains of their descendants, and the effects revealed by Radvansky in his experiments appear to demonstrate this legacy.