Foucault’s Panopticon and the Creation of Docile Bodies

“Visibility is a Trap”

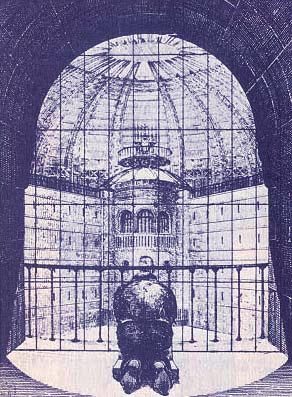

The tower stands solitary within the large, circular room, lined closely by small, confined prison cells. The inmate’s form is backlit by the burning sunlight, which streams through the bars of the small window etched into the outer wall of his concrete domicile, illuminating his every move. He casts his glance continuously at the drawn venetian blinds hanging over the glass paned portions of the tower. He wonders how many prison guards are meeting his gaze and gloating over his apparent helplessness. Enraged, wishing to strangle the next officer that smugly walks past his cell, he instead does nothing; he knows that they are watching, hoping that he will make a mistake. In anguish, he returns to his bed, hoping that sleep will soothe his overwhelming claustrophobia, but looks towards the looming structure one last time. The tower has been empty for over two weeks now.

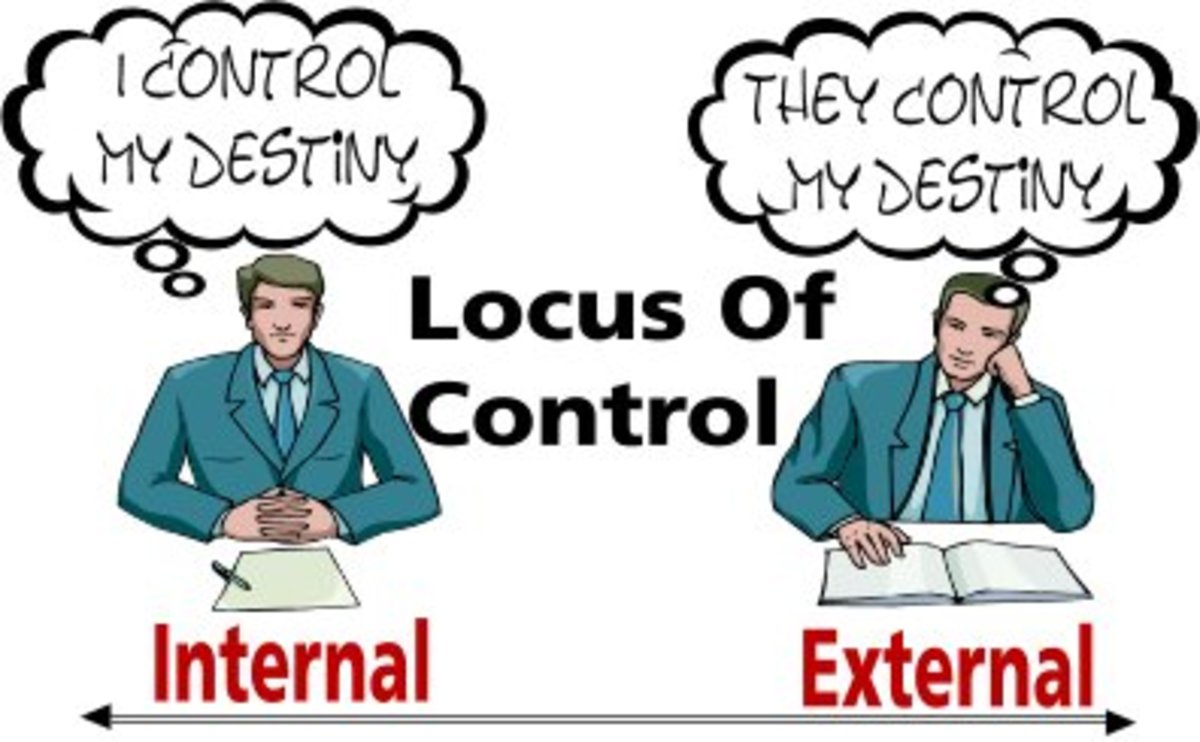

This scenario, albeit fictitious, showcases the ultimate goal that Jeremy Bentham, a British Utilitarian philosopher of the late 18th century, imagined achieving through his construction of the Panopticon: blatant submission. In his vision, Bentham conceived a prison building, punctuated in its center by a massive structure that would allow 360° surveillance of its surroundings. The prisoners, placed in such a way as to inhibit any communication, thence became the victims of permanent visibility. With no manner of assessing whether guards were stationed atop the observation tower, inmates were transformed into a docile mass, threatened by the omniscient presence of their incarcerators.

Bentham’s hope that his idyllic prison structure would become integrated into greater society, consequently permitting the preservation of democracy within a capitalist society, was confirmed by French Philosopher Michel Foucault, who, in the 20th century, revealed how the panopticon’s methods of discipline had, in fact, been adopted by the general citizenry. In order to grant credence to his assertion, Foucault highlighted numerous aspects of society that echoed the theory of panopticism, in which the creation of passive, self-regulating bodies resulted from an instilled fear of an omniscient entity.

“Prison continues, on those who are entrusted to it, a work begun elsewhere, which the whole of society pursues on each individual through innumerable mechanisms of discipline.” – Michel Foucault

What follows are several features of society that are an integral part of the panoptic machinery:

-Santa Claus: “He sees you when you're sleeping, he knows when you're awake, he knows if you've been bad or good, so be good for goodness sake! “.

This is an ideal example of how Santa Claus, utilizing surveillance, forces discipline upon children. The promise of reward motivates the young to behave in hopes of passing judgment on Santa’s famed list of those considered “good” or “bad”.

-Tracking: Be it via mobile phone, On Star, or customer loyalty cards, an individual’s actions are monitored and scrutinized.

-Religion: Considered a societal necessity, religion aids in establishing social cohesion. For the individual within said society, his thoughts, decisions, and acts are manipulated by the constant menace of eternal damnation.

-D.A.R.E.: Drug Abuse Resistance Education encourages children to observe and report any illicit activity, even within their own family unit.

-Peer-to-Peer Networks: Whether through Facebook, Twitter, Myspace, or any other of the countless social media sources on the Internet, one’s life is publicized for the world to consider. What one is willing to publish about oneself is -generally- carefully considered in order to avoid negative ramifications, thereby molding our public appearance in a manner that appeases authoritative figures.

Considering the methods of surveillance imposed upon the populace, it becomes far simpler to see what drastic effects these techniques have on the individual and how submissive we as a people have become.

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (NY: Vintage Books 1995) pp. 195-228