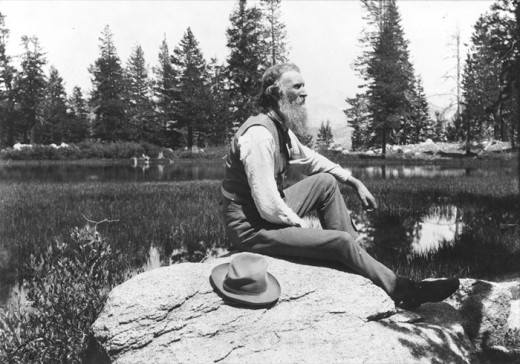

Founding Fathers of the National Park Service: John Muir

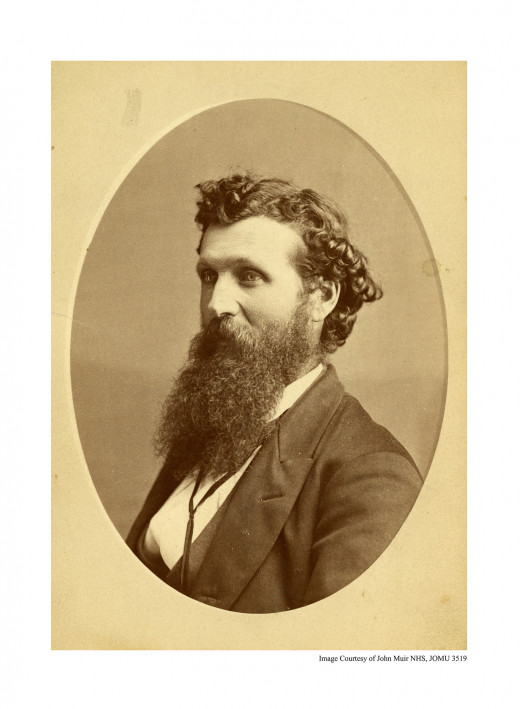

Early Life

As a youngster, Muir was raised by a strict, religious father in Indiana. The primary use of his time – in accordance with his father’s wishes – was spent in studying the Bible. Before he was a teenager, he could recite nearly the entire book.

Always smart, he went on to study botany and geology at the University of Wisconsin. His intellect exceeded merely his studies, however, and he fiddled regularly with new ideas. He was creative, and always inventing.

He picked up work at a factory and considered himself blessed when the blindness he suffered from an accident there turned out to be temporary. Grateful to have his vision returned to him, he left the factory and began what would turn out to be quite the adventure.

Starting over

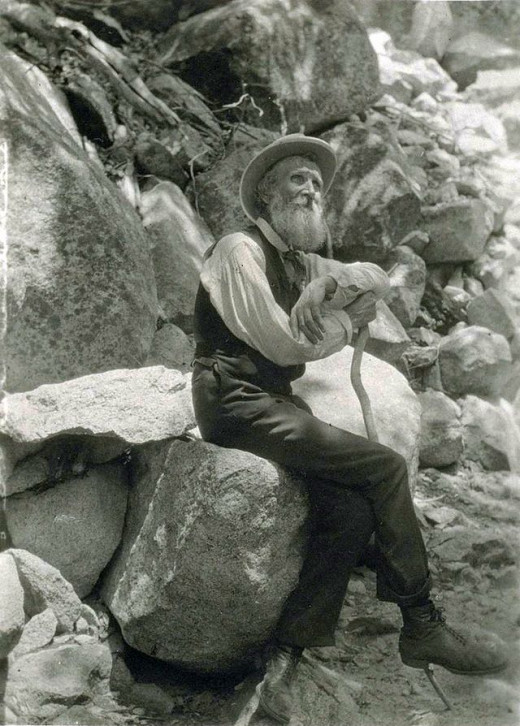

From Indiana, he walked southward. The pleasure he found in walking would stay with him for the rest of his life. His famous nature walks in the parks of the west are legendary. On this walk, however, he wasn’t teaching – he was learning.

His sketchbook filled with pencil drawings of grasses, shrubs, flowers, and trees – his curiosity and fascination with nature getting primed for the great western spaces with the relatively plain flora of the east.

The walking part of his sojourn ended in Florida. From there, he took to the seas and sailed to California, where he resumed his sauntering. He walked, sketchbook in hand, from the beautiful city of San Francisco (one he loved, but would later find fault with) to the “Range of Light,” the towering Sierra Nevada mountains.

His first introduction

In 1869, he was first introduced to Yosemite by James Mason Hutchings. Hutchings hired Muir to build a sawmill, which Muir did quickly and competently. Off-hours, he spent his time wandering the streams, the rocks, and the mountains of the Yosemite Valley.

The geologist in him began theorizing on the history of the valley. Clearly, he concluded, the valley was formed by the slow and powerful movement of glaciers. Muir was particularly fond of glaciers and, later in life, was pleased to have hands-on experiences with them in other parts of the country.

Spreading the word

He left the valley in 1873, choosing instead to spend his time in Oakland. Relocating not out of boredom of nature, but rather for the love of it, Muir began writing about what he’d seen. His work appeared in several, nationally distributed outlets. The poetic and spiritual portrayals of nature that he penned quickly brought him fame. He was no longer John Muir. He was the John Muir.

With his writing, the world was introduced to a philosophy that was somewhat unique to the continent. Instead of suggesting that man conquer nature, Muir proposed that he participate in it. “We are now in the mountains and they are in us,” he would proclaim, “kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us.”

In nature, Muir saw God, and that was something worth appreciating.

True love

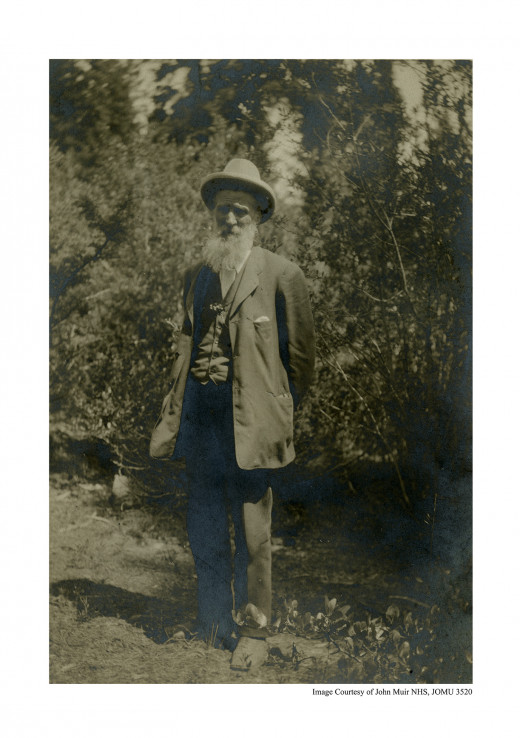

Several years later, in 1880, he was married to Louie Strenzel, a woman who seemed to understand her husband. They lived and worked together on an orchard in Martinez, California. But the man grew fidgety. The mountains were calling.

At the insistence of his wife, Muir ventured back out into the wilderness. This time, however, he didn’t return to Yosemite, but – instead – traveled north. Visiting Mt. Rainier (in Washington state) and Glacier Bay (in Alaska), he was once again thrilled with the beauty of nature.

His writings reflected his travels and, it seemed, every place that the man wrote about became popular in the public’s eye. He was the modern Benjamin Franklin – a likable, well-spoken gentleman that was beloved everywhere he went.

John Muir on the Mountains [A VERY brief excerpt from the Ken Burns' amazing "The National Parks: America's Best Idea"]

Preserving the land

As he grew in fame and fervor, his attentions were focused heavily on preservation. Though he cared for many of the nation’s greatest lands, Yosemite was always on his heart.

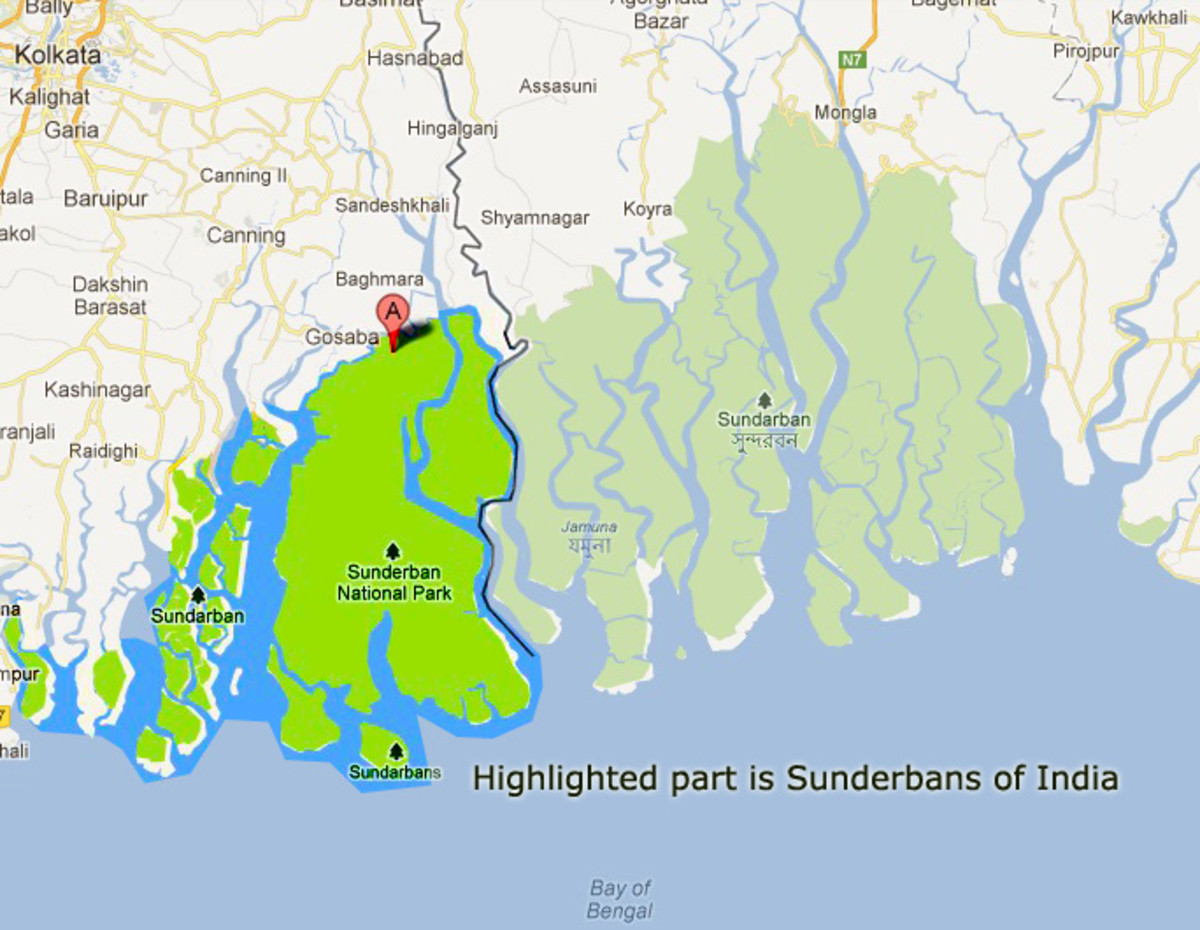

Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove had been under state control since the 1860s, but Muir had higher hopes for his beloved land. Following the example set by the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, he wished to see Yosemite transferred to the federal government. In this way only, he was certain, could the lands be protected forever.

In 1889, Muir wrote a pair of articles for Century Magazine at the beckoning of its editor, Robert Underwood Johnson. They called for federal protection, and he was elated when the federal government passed legislation following almost all of his suggestions except the biggest one. It remained in the hands of the state.

Later, Muir would be able to lead a successful campaign to change the ownership. During this time, however, his popularity among the conservationists of the day was incredibly high, and, using it, he co-founded The Sierra Club with Henry Senger, a University of Berkeley academic. The club opened its doors in 1892. John Muir was promptly elected president, and remained so until his death, 22 years later.

Learn more about John Muir and the National Parks

Preservation President

During the early years of the Sierra Club, Muir became associated with another nature-minded man, named Gifford Pinchot. Both had a passion for the wilderness. Both wanted to protect it, and – initially – this was enough to make them companions. Their acquaintanceship ended, however, after the men realized how different their plans for protecting the nation’s lands truly were.

John Muir believed in the pristineness of nature. His stance was clear. “Everybody needs beauty…places to play in and pray in where nature may heal and cheer and give strength to the body and soul alike.” These places weren’t just special, they were vital. And they needed uncompromised protection.

Pinchot, on the other hand, believed that nature – while maintaining some level of spiritual value – also had practical uses. His position, one that appreciated man’s need for water, stone, and wood, called for limited protection. Whereas Muir advocated chopping no trees, Pinchot suggested chopping some. John Muir shouted preservation, Gifford Pinchot, conservation.

In many ways, both men were right. Eventually, their opinions would be embodied in the philosophies of two similar, but very different federal bodies: the National Park Service, and the U.S. Forest Service. And both men would have their victories, too. After all, Muir successfully saw the creation of several National Parks in his lifetime.

It was Pinchot’s victory a few years later that would most trouble the old man, however.

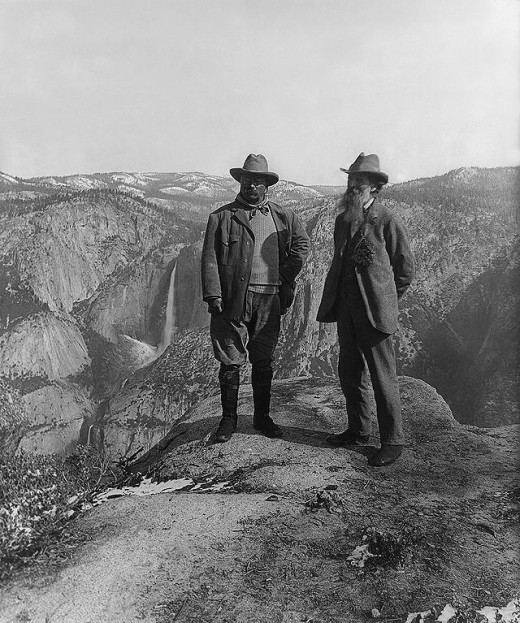

America's greatest night of camping

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt – the greatest environmentalist to ever sit in the Oval Office – visited Yosemite National Park. The fame of John Muir was sufficient enough to merit him a by-name invitation to join the president, and so he did.

Muir passionately expounded upon the geology, natural history, and beauty of Yosemite, never forgetting the political power that his companion held. He let much of Yosemite do its own talking, but also made sure to explain the benefits that could be secured by placing the area under federal control.

Roosevelt was able to convince Muir to break off from the gang of followers, and the two men spent the evening alone in the wilderness. Chatting late into the darkness, they had perhaps the most envied night of camping night in American history. A light, Sierra Nevada snowfall marked the ground by morning and made the impression Muir had only hoped to. The impact upon Roosevelt was enormous. He never forgot the experience, and his love for nature only became more evident from that point forward.

"Dam Hetch Hetchy!"

In his old age, John Muir spent most of his time fighting on behalf of Hetch Hetchy Valley. The possibility of damming the Tuolumne River had been discussed for decades and the growing population of San Francisco, to the west, became an increasingly persuasive point.

Muir famously remarked, “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

On the opposite side of the argument were men like Muir’s rival and former friend, Gifford Pinchot, who stood convinced that damming the river would serve the greatest good to the greatest number of people.

In the end it was not water, but fire, that had the final say. A fire in the city of San Francisco was enough to take the on-again, off-again damming plans and finalize them. In 1913, the river was dammed and John Muir was heartbroken.

The Grandfather of American National Parks

A year later, on Christmas Eve in 1914, John Muir died.

He’s been called the “patron saint of the American wilderness.” He’s been called “an American pioneer” and “an American hero.” His writings number in the hundreds and his name belongs to mountains, glaciers, schools, beaches, roads, and even an asteroid. He’s been featured on stamps on the California state quarter.

But his greatest legacy isn’t in name. It’s in spirit. John Muir is the grandfather of the American National Parks, the nation’s grandest and most beautiful lands.

![Ken Burns: National Parks Set - America's Best Idea [Blu-ray] [Enhanced CD] (Set of 6 discs Plus CD Soundtrack)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51x6E1TA4JL._SL160_.jpg)