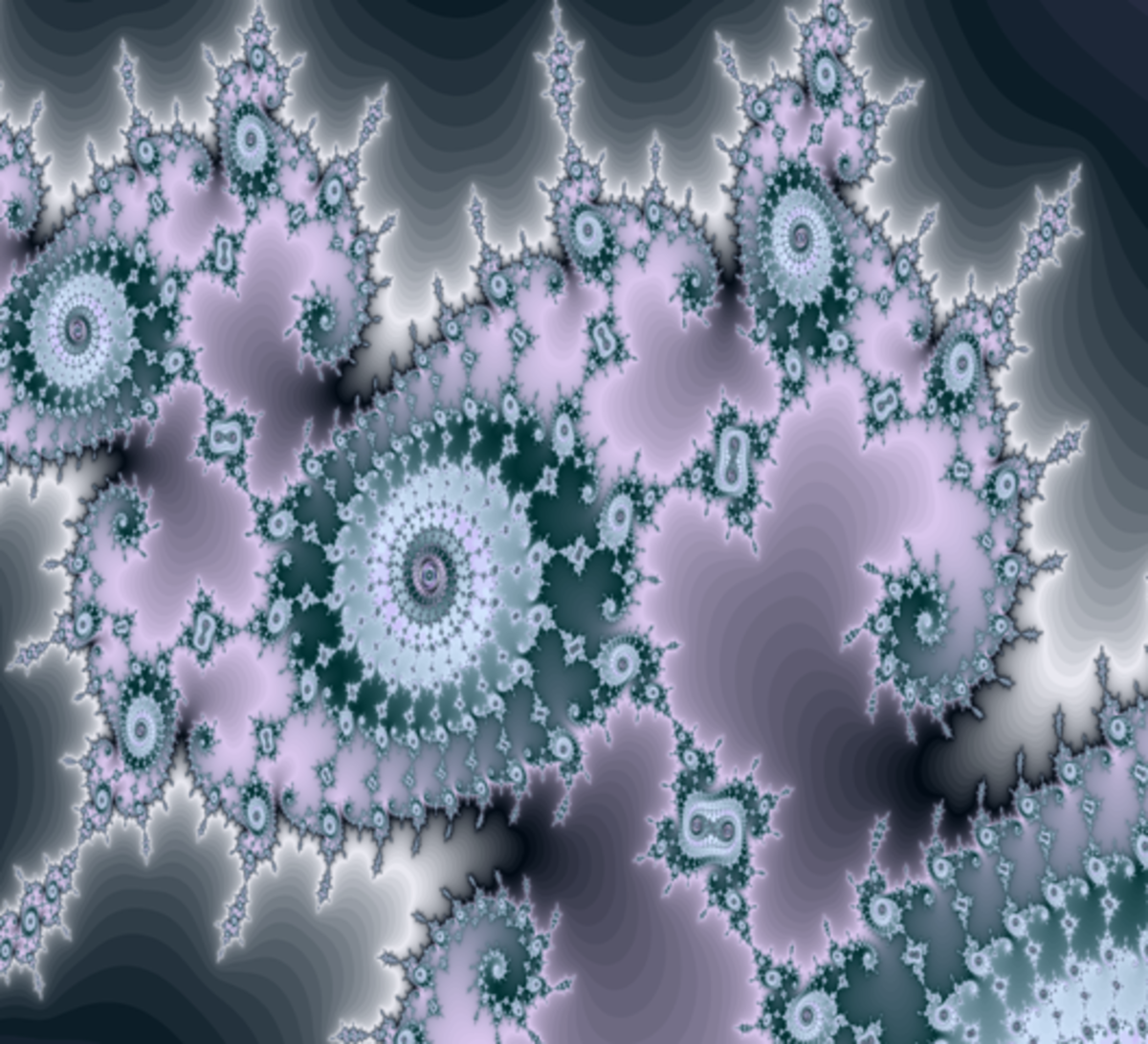

Fractals, time and infinity

In 1982 mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot described objects with Fractional Dimension - which he called Fractals - an idea vaguely reminiscent, if only fancifully, of Lovecraft's beings living in the spaces between worlds. Mandelbrot merely brought fractional dimensions to public notice and the notice of specialists in other fields, especially physics – Besicovitch coined the term fractional dimension in 1929 [1]

When the idea of a fractal is examined closely it seems the mystery of fractional dimensions can be seen to result from a confusion of two definitions of dimension, the notion of dimension as a degree of freedom and of dimension as a measure of the content of a body.

Rucker used fractals to discuss the implications of infinity in the small thus giving fractals a role in philosophy as well as physics, mathematics and art and raising the possibility the universe maybe discrete but not have a minimum length scale.

Topological dimension

At the start of the twentieth century mathematicians got a number of rude shocks, mainly from Infinity, which, having suffered multiple efforts at banishment from mathematics took its revenge. Cantor had shown that a line an inch long had as many points as a line a mile long, and as many points as a square or a cube. It was time to look at what was meant by dimensions.

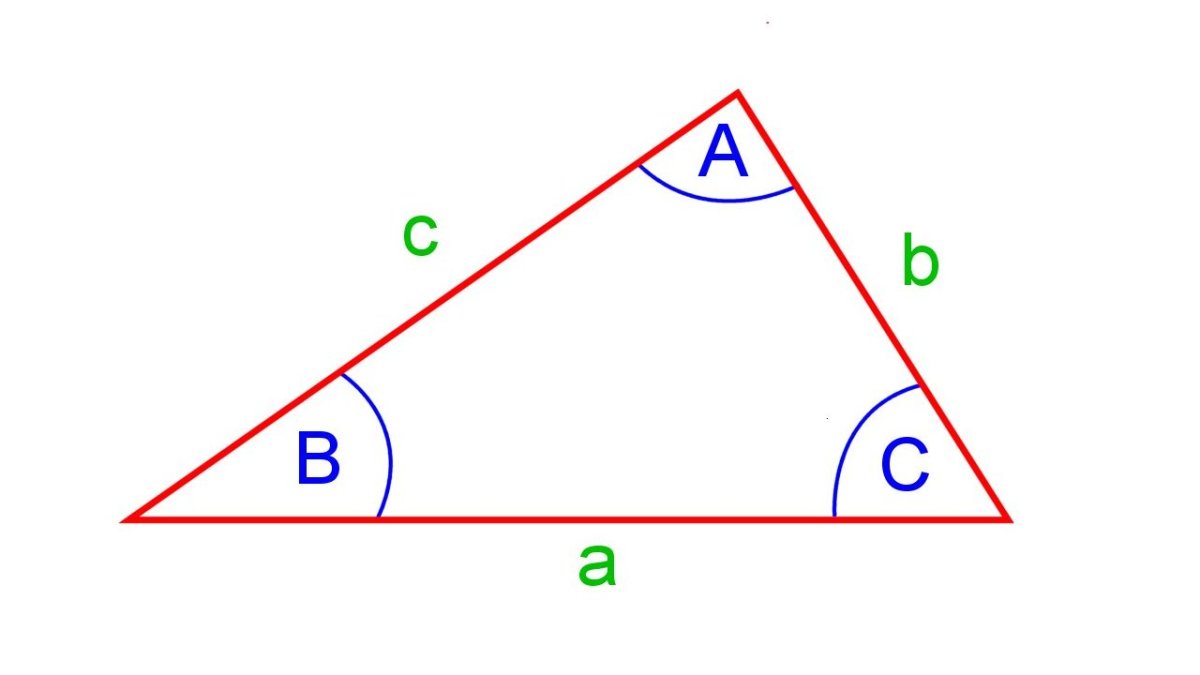

Naively dimensions equate to degrees of freedom, a line has only one degree of freedom, and a square has two. Physicists regularly deal with spaces with an infinite number of degrees of freedom. And a point in an N dimensional space is located by an ordered set of N numbers. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, one can pair off each point in a line with a corresponding point in a square or a cube, which mathematicians disliked.

A topological space is essentially a set and a collection C of its subsets such that the union and intersection of any finite collection of these subsets is also in C. Once mathematicians started to think about definitions of dimension a number of ideas surfaced but each definition gave a different result on the most general topological spaces.

Fortunately....

All the major definitions gave the same results if the space was also a metric space – a space on which the distance between any two points can be defined in a common sense way [3].

So that's alright, but what about fractional dimensions?

Fractional dimension

Another common sense aspect of dimension defines dimension of a body by how the amount of stuff it holds increases as it gets bigger ( technically this is called its measure ). The area covered by a square increases as the square of the length of its side. The area included in a cube increases as the cube of the length of a side. In the other direction a set can be non empty by have measure zero, for example the rational numbers are dense in that any interval of numbers contains an infinite number of rational numbers but it has measure zero in that an arbitrary number picked out of this region has an infinitesimal probability of being a rational number.

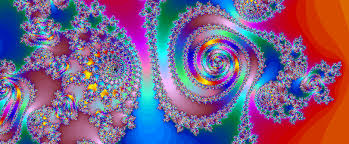

So far so good. What Mandelbrot rediscovered and took to a new level is that some objects do not follow this simple rule. The amount of stuff included in a Fractal object increases by a power that is not an integer.

Technically every subset of a metric space has a dimension called the Hausdorff dimension normally equal to its topological dimension (number of degrees of freedom) but some sets, known now as fractals have a Hausdorff dimension greater than the topological dimension. Fractals also have the property that a subset of the fractal is identical to the fractal, an aspect that has captured the imagination of artists, mathematicians and theoretical physicists.

Fractals and infinity

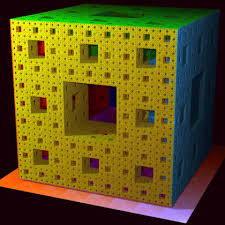

The simplest case is a fractal dust in two dimensions typically created by starting with four points arranged around a central square, replacing each point with a smaller square and rescaling the result so that each small square is the same size as the original. A similar dust could be created starting with a triangle and extension to three dimensions using either a tetrahedron or a cube. In fact any set of points arranged as a polygon or polyhedron symmetrically arranged round their centroid could be used as a starting point.

Another way of looking at this dust is to assume each of the initial set of points consists of a set of points that replicates the whole. This can be seen by zooming in, and, if the zooming process can be repeated indefinitely the space in which this takes place will not have a minimum length scale nor will the set of points be dense in the containing space, unlike the case of rational numbers which are dense on the real line in that there are an infinite number of rational numbers in between any two rational numbers. It is possible however to imagine a universe in which particles can only occupy the sites of some (possibly only statistically) self similar fractal dust and may even be dense in this space ( assuming such a dense fractal can exist). It is an open question whether our universe is such a space but quantum field theories make it unlikely however Wolfram's notion that physics represents the action of cellular automata would seem to call into question the validity of a quantum field explanation of physics. Much more research is needed.

Regardless of the speculations in the last paragraph Rucker [4] uses a fractal dust to illustrate the possibility of a universe with cyclic size scales. One of his speculations is that if the universe is a fractal dust then there is a logical possibility that zooming in enough will reveal a universe identical to the one from which we started, perhaps with someone just like you reading an article identical to this one. And this leads to other speculations.

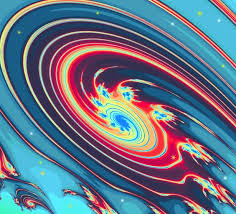

If we start with only two points we get a fractal dust arranged along a line. Since we mainly experience time as linear, though cultures viewing time as cyclic may experience it as helical, each such point of the line may be regarded as a universe at a given point of time. Again there is the possibility of a universe in which time possesses cyclic scale.

Intriguingly Conway's famous game of Life, which is a universal computer can create fractals. More precisely correctly chosen initial conditions result in two dimensional fractal dusts [5]. There seems to be no extension of this to the three dimensional case. These self replicating structures tend to support Wolfram's theory of physics in terms of cellular automata and the notion of Physics as Computation [ e.g 7] and to the possibility our universe is a (possibly analogue) simulation [8,9]. They also enhance the possibility of a fractal universe and possibly fractal time, though much research needs to be done on this.

In brief

Mandelbrot popularised the intriguing notion of fractional dimension and specialists in other areas took up the concept for use in Physics and other fields. He did not invent the notion, and the idea of a fractional dimension originated many years earlier. Topological dimension, which intuitively covers the idea of degrees of freedom is not fractal dimension which relates to the idea that the dimensionality of an object is related to the way the amount of stuff it holds is related to its size.

Objects with fractional dimension have important philosophical consequences, have proven valuable in theoretical physics and may suggest useful directions for further exploration.

Further reading

-

A. S. Besicovitch (1929). "On Linear Sets of Points of Fractional Dimensions". Mathematische Annalen 101 (1): 161–193. doi:10.1007/BF01454831.

-

A. S. Besicovitch; H. D. Ursell (1937). "Sets of Fractional Dimensions". Journal of the London Mathematical Society 12 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-12.45.18.

-

Hurewicz, Witold; Wallman, Henry (1941), Dimension Theory, Princeton Mathematical Series, v. 4, Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, MR0006493.

-

Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite

Rudy Rucker, Princeton University Press 2004 ISBN: 9780691121277 (paperback) -

Lines to Fractals https://webfiles.uci.edu/bwisialo/www/gameoflife2.html