H80 CG08Industry and Transportation

INDUSTRY AND THE WEB OF TRANSPORTATION

There have been two great economic “revolutions” in human development. The first of these was the domestication of plants and animals, which occurred in our dim history coined as Agricultural Revolution. This agricultural revolution ultimately resulted in a huge increase in human population, a greatly accelerated modification of the physical environment, and major cultural adjustments. The second of these upheavals is the industrial revolution, which is still taking place.

The industrial revolution, which began in the eighteenth century, released for the second time in history undreamed – of human productive powers. Today, the industrial revolution, with its churning up of whole populations and its restructuring of ancient cultural traditions is still running its course. There are lands still largely untouched by its machines, factories, new methods of transportation, and starting communication devices. Western nations, where this revolution has been underway the longest, are still feeling its sometimes painful, sometimes integrating effects.

Industry, of course, is a livelihood, and the livelihood is a facet of culture. In western culture, the majority of the population owes its livelihood either directly or indirectly to industry and its related products and services because industrialization is closely interwoven with the physical environment and with other facets of culture and because industry is unevenly distributed. Thus, we will discuss industrial ecology, the place of industry in cultural integration, and the industrial landscape.

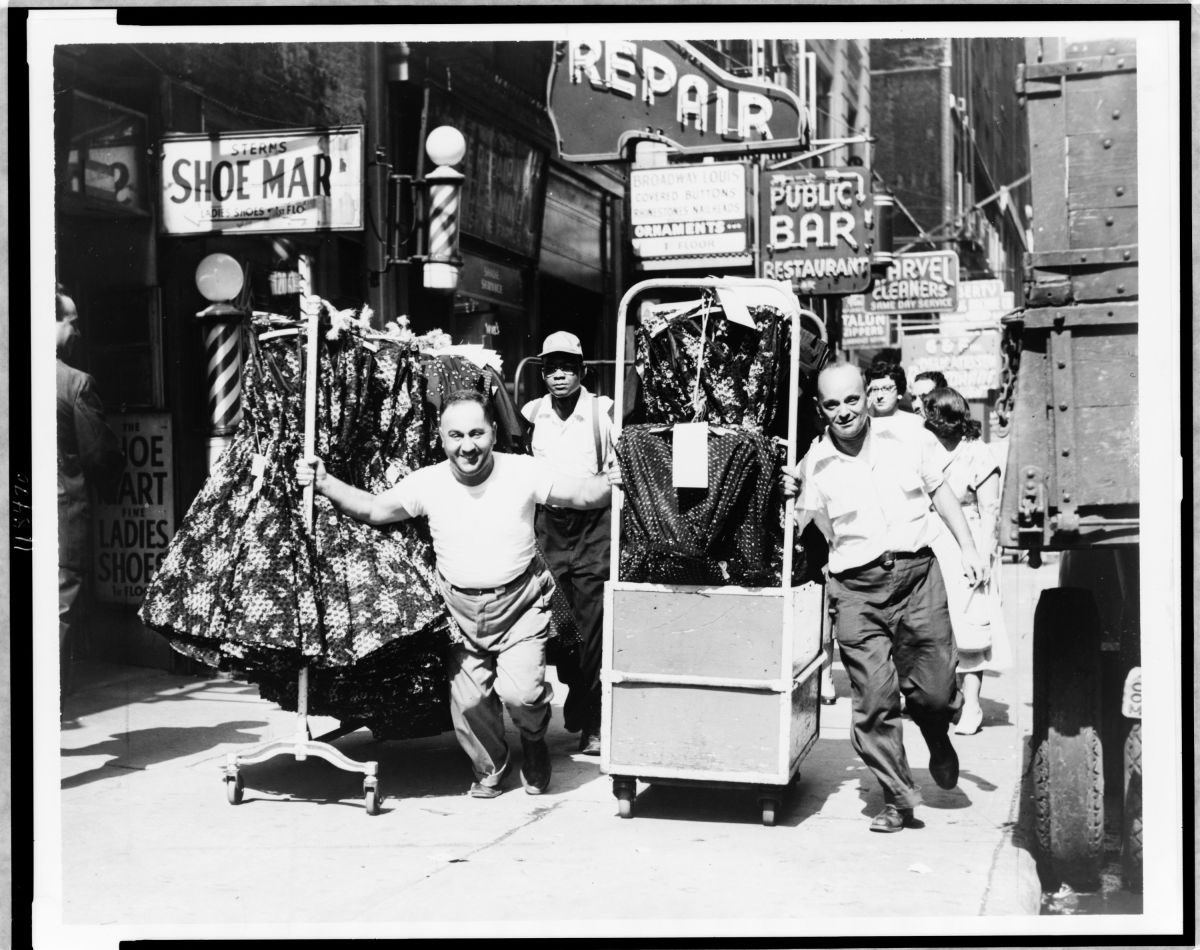

The cultural geographer distinguishes three types of industrial livelihood. The first are the primary industries which are involved in extracting natural resources from the earth renewable and non- renewable resources. As a rule, however, primary industries are more likely to develop in conjunction with manufacturing districts. Zones of primary industry distant from manufacturing centers are likely to spring up only if the resource is very valuable and rare, worth enough to withstand the cost of transporting it long distance. Next are the secondary industries which are clustered in the northeastern part of the country, a region often referred to as the American Manufacturing Belt. Many different types of manufacturing are found within the world’s major regions. The third are the tertiary industry which involves the distribution of goods and services. Tertiary institutions include wholesale and retail outlets, banking and other financial services, governmental and educational services, medical facilities, and the many other business and service functions upon which we depend daily. The map of industrialized and non-industrialized area is a good measure of how far the industrial revolution has spread. Society and culture were overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. Cottage industry, by far the most common, was practiced in farm home and rural villages, usually as a sideline to agriculture. While the cottage and guild systems were different in many respects, they did share one trait. Both depended on hand labor and human power. These changes were so basic as to render such traditional systems largely obsolete. Our lives are a good constant adventure in shrinking space. But until the eighteenth century, every human activity had to grapple with the fierce resistance distance put up. Weather, human desires, and physical obstacles like mountains, seas, wide rivers, strait, or marshes stood between the trader and the market, the army and its object of conquest, the traveller and his destination, or even a letter and its intended recipient. Before the eighteenth century, distance had been a relatively constant factor for centuries. In terms of travel, the Mediterranean was about the same “size” in the sixteenth century as it had been in Roman times over 1000 years earlier. Traveling times did not change much until the nineteenth century.

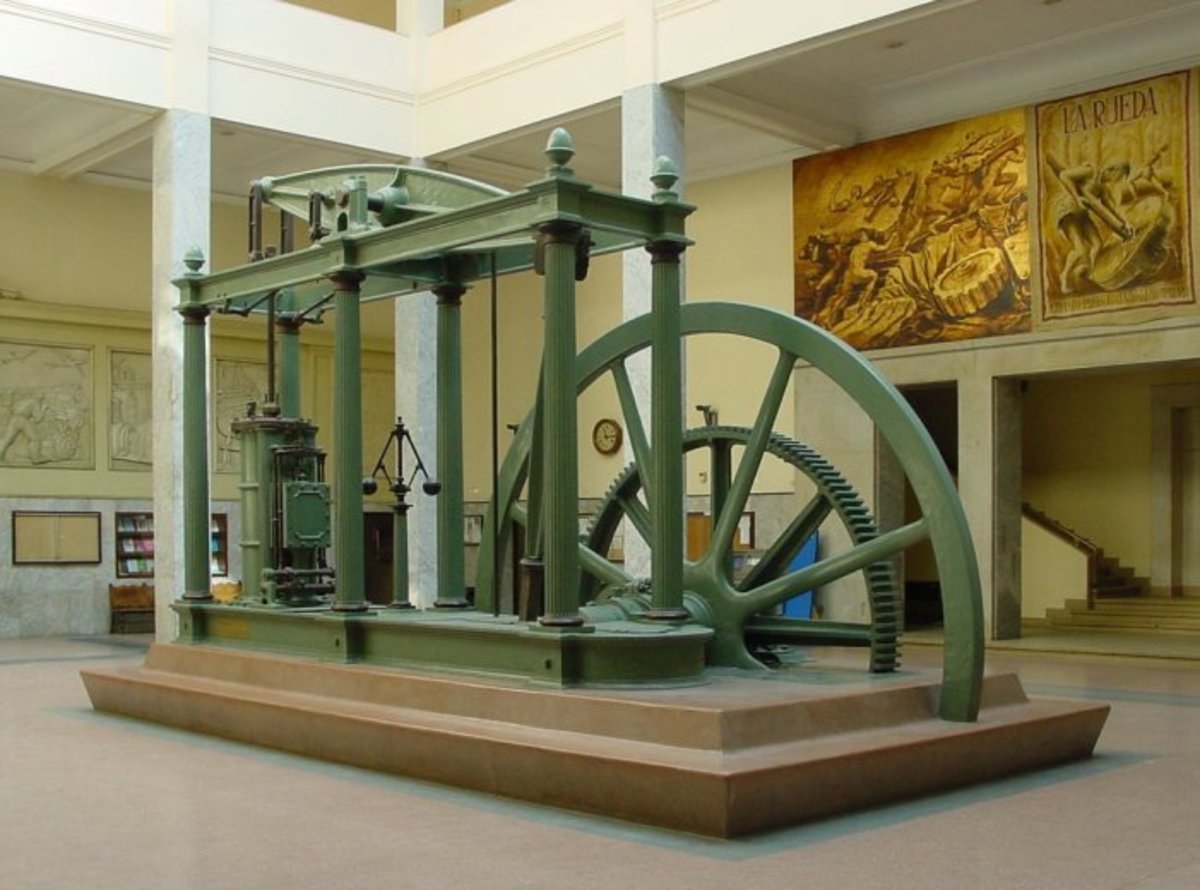

The industrial revolution was not an impersonal event. It took a continuing toll in human pain, human misery, and even death. While the process if industrializing production made fortunes for some, it maimed others. No longer would the weaver sit at a hand loom and painstakingly produce each piece of cloth. The machines were driven by water steam and the burning of the fossil fuels. We know a lot more about the origins and diffusion of the industrial revolution than we do about the beginning of agriculture. Mechanical looms were invented, and flowing water, long used as a source of power by grain millers and was harnessed to drive the looms. In the beginning, the industrial revolution was really a cotton revolution. In England, until about 1830 “factories” or “industry” meant the production of cotton cloth. It was far slower to develop because, unlike industries oriented toward the consumer market, iron and steel plants involved heavy investment and little initial return. Nonetheless, revolutionary developments in iron and steelmaking soon occurred. Traditionally, the metal industries had been small- scale, rural enterprises. Techniques had changed little since the beginning of the Iron Age two thousand years ago before. The old traditions, techniques, the rituals of steelmaking were swept away and replaced with a scientific, large-scale industry. Mass production of steel was the result later on. The adoption of the steam engine necessitated huge amounts of coal to fire the boilers, and the conversion to coke in the smelting process further increased the demand for coal. New mining techniques and tools were invented, so that coal mining quickly became a large-scale, to transport. Similar modernization occurred in the mining of iron ore, copper, and other metals needed by rapidly growing industries. The individual stimulus that led to these transportation breakthroughs was the need to move raw materials and finished products from one place to another, both cheaply and quickly. The creator of the industrial revolution, also invented the railroad and initiated the first large-scale canal construction.

British government actively tried to prevent the diffusion of the various inventions and innovations that made up the industrial revolution. Continental Europe was the first to receive its impact. The diffusion of railroads in Europe provides a good index to the spread of the industrial revolution there. In the first third of the present century, the diffusion of industry and modern transport spilled over the Soviet Union. In the United States, the development of the railroad affected both the distribution of industries within cities and within regions. Whenever it went, the railroad concentrated industry; yet, at the same time, its presence allowed for a greater regional diversification of industrial tasks. Few cultures exposed to industrial innovations have proved resistant to them. The incredible expansion of industrial production in some countries was based on the creation of markets for those products in other countries. The spread of the railroad in the nineteenth century had an explosive impact on the quality of urban life. Not merely noise and soot but the industrial plants and debased housing that alone could thrive in the environment it produced. As late as 1815, India exported to England cotton goods worth fifty times to British cotton goods it imported. However, imperial Britain, which had used high tariffs to protect its own cotton production, opened India to “free trade”. Britain’s political and military pressure helped it conquer a world market for its exploding industrial plant. In a sense then, it “spread” the industrial revolution across the planet. However, in practical terms, it turned its colonies into giant plantations or mines for the production of raw materials to be processed in Britain. As early as 1870, the results of the spread of industrialization via imperial expansion were in. The gap between the “developed” and the “undeveloped” countries that is so familiar to us today was already a reality. Present-day industrial expansion in the age of corporate globalism seems to be intensifying this gap, in many cases increasing the dependence of less industrialized on more industrialized nations.

Between 1960 and 1968, for instance, American-based corporations took, a result, the industrialization of “undeveloped” countries is actually increasing the power of the world’s leading industrial nations. In fact, today we face a world in which, while industrial technology has spread everywhere, the basic industrial power of the planet is more centralized than ever. Actual barriers within cultures to industrial diffusion have usually been economic or physical in nature, based on remoteness or shortage of necessary natural resources. As a result, we are well advised to look into the themes of cultural ecology and cultural integration for a better understanding of spatial distribution of industries and the causal interaction of industry and environment, industry and culture.

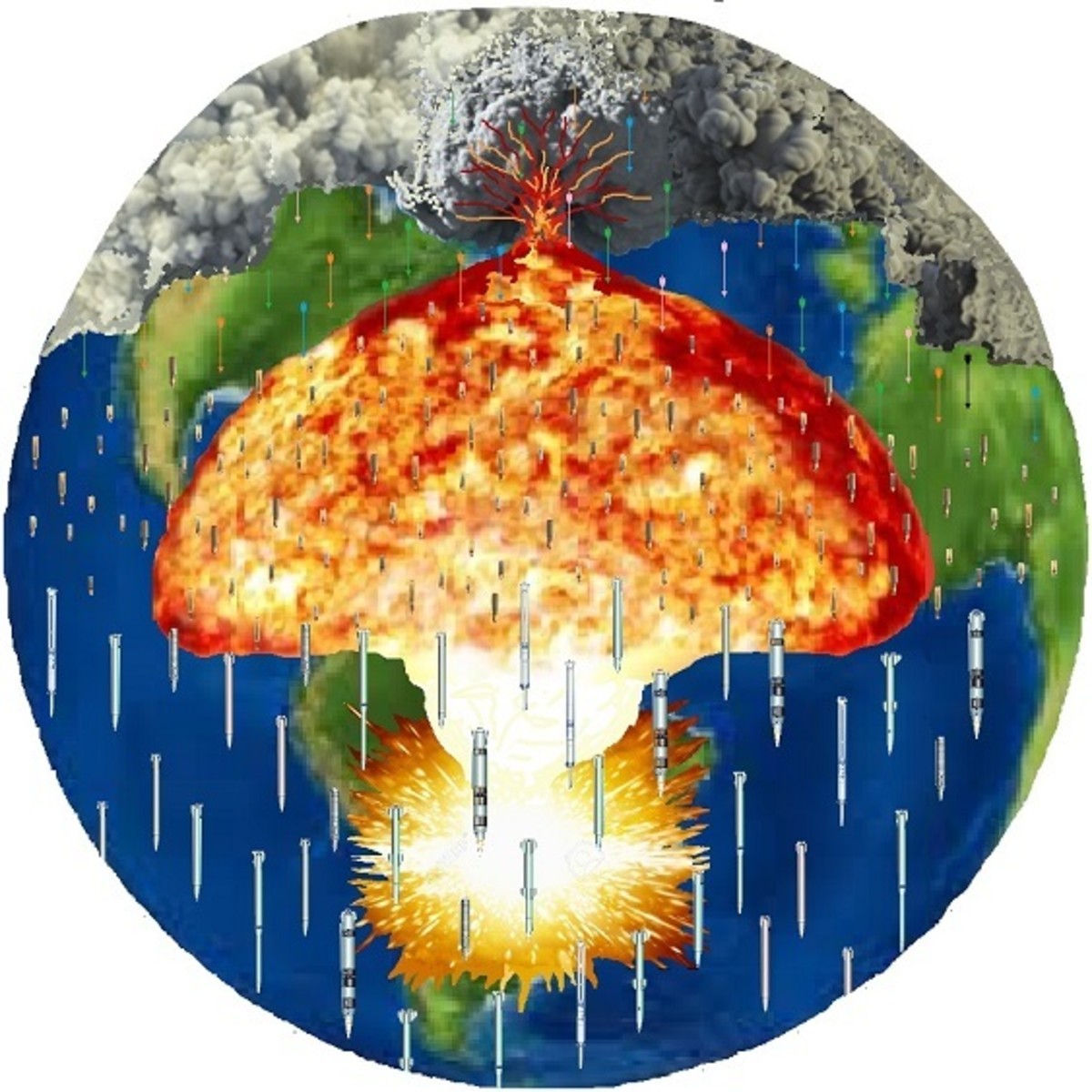

The diffusion of the industrial revolution has occurred only at enormous environmental expense. By its very nature, the technology of modern industry consumes nonrenewable resources and destroys the natural environment. Massive pollution of the air and water seems to be an avoidable by-product of mechanized industrial processes, at least in our present state of knowledge. While pollution and environmental alteration could be significantly reduced, which has become so integral a part of our culture in the past two centuries, is simply ecologically untenable and cannot be maintained. The technology of the industrial revolution has demanded that we modify our habitat on a previously undreamed-of scale, and at the same time has provided us with the tools and techniques to carry out that massive modification. But if the industrial revolution has governed in part by that same environment, the spatial distribution of industry in particular has been influenced by environmental considerations.

In the early stages of the industrial revolution, industries grew where the raw materials were. The reason was simple. The development of efficient means of mass transportation only came about a century after the beginning of the revolution. Before about 1830 or 1840, it was impossible to move bulky, heavy raw materials. The industrial system as a whole is based on using those raw materials. As a rule, we can say that manufacturers will locate near their raw materials. If there is a great loss of weight or bulk in the manufacturing process, or if the finished product is less perishable than the raw materials from which it is made. In industrial location we should also recognize the phenomenon called industrial inertia. This refers to the tendency of industries to remain in their initial location, even after the forces that attracted them there have become obsolete. Thus, some industries that were drawn to the sources of raw materials in the 1700’s or early 1800’s before the advent of modern modes of transportation remain in the same location. This inertia occurs because capital investment in the form of land and structures would have to be sacrificed if the industry were located. In addition, the present labor force would be difficult to relocate with the industry.

The quantity of energy consumed by industries measured either as a total amount or per unit of goods produced, has increased greatly since the beginning of the industrial revolution. In a proper sense, energy was not power source. Rather, the rapid increase of power use began with the shift from water power to the steam engine and accelerated with the subsequent adoption of other power sources, in particular, electricity. As a result of long distance shipment of fossil fuels, industrial plants requiring large amounts of energy were forced to locate where water power or coal was available. Aluminum industry was still strongly attracted to the sites of energy production, which consumes huge amounts of electricity in the process of converting the raw materials bauxite into aluminum. Hydroelectric sites are preferred.

It seems unlikely, therefore, that rapidly increasing energy costs will cause any significant relocation of manufacturing industries, because transportation expenses constitute a smaller-than-ever proportion of total energy costs.

Only in cases where very large amounts of land are required, or where special characteristics such as the abilityto support heavy loads are required, does terrain become a major factor in industrial location. The role of climate in industrial location is hardly more significant than that of terrain. Increasing the ability to control indoor atmospheric conditions has greatly reduced the impact of climate and weather in choosing location. However, modifications of natural atmospheric conditions can be achieved only through the application of energy and the use of machinery, each of the factory in an area’s whole substantial air conditioning is required will be practical only if there are compensating advantages. Thus, industry both shapes the environment and is influenced by it. But even more pronounced relationships exist between industry and other facets of culture. With that in mind, let us turn now from cultural ecology to the theme of cultural integration. Labor availability and costs are a factor in choosing an industrial location. Most affected are labor intensive industries, for which labor costs from a large costs from a large part of total production costs.

Manufacturers consider several characteristics of labor in deciding where to locate factories: availability of workers, average wages, necessary skills, and worker productivity. Traditionally, workers with certain skills tended to live and work in a small number of places, partly as a result of the need of the person-to-person training in handling down such skills. Factory “migration” itself is an increasingly powerful force on the labor, or labor that can be trained quickly and cheaply, relocation be economically depressed rural areas can result in higher profits. The main attraction of such areas in the large supply of cheap labor is a contrast to the high wages typical in established industrial districts.

Small town areas are gradually decreasing due to the imposition of the uniform regional or national wage scales, this eliminating the domestic attraction or cheap labor. Such factories, despite relocation costs, quickly drive up corporate margins. In addition to the ability of these corporations to plan on such an international scale and to shift the production of given product thousands of miles away.

A market is the area in which a product may be sold in a volume and at a price profitable to the manufacturer. The size and distribution of markets are generally the most important factors in determining the spatial distribution of industries. Certain industries, man’s economic sense, must situate their factories among their consumers if they are to minimize costs and maximize profits. Similarly, the type of marketing being served an affect location of industries. Some manufacturers supply highly clustered urban markets, while others, such as the makers of farm machinery, cater to a more dispersed body of consumers. As a rule, though, we can say that, a Western industrial culture, the greatest market potential exists where the largest numbers if people are found.

The multiplier effect will produce serious overcrowding and excessively clustered population. This intense concentration of industries and population is characteristic of the most industrialized nations. Instead, we are dealing with a highly complex international corporate structure planning on a gargantuan scale. As George Ball, former government official and now partner in an international investment banking firm, commented:”working through great corporations that straddle the earth, men are able for the first time to utilize world resources with an efficiency dictated by the objective logic or profit”.

On a world scale, the effect of corporate planning is the internationalized production. “Since the decision making mechanisms of these locally based company are geared toward the profit structures of the parent corporation and not toward the local economies in which they exist, their decisions, some scholars have argued, may well result in the further impoverishment of already poor countries.

Political influence on the spatial distribution of industrialization is at hand. Such intervention typically results from a desire to establish strategic, militarily important industries that would otherwise not develop; to decrease vulnerability to attack by artificially scattering industry to many parts of the country; to create national self- sufficiency by diversifying industries; to bring industrial development and a higher standard of living to poverty-stricken provinces; to place vital strategic industries in remote locations. Far removed from possible war zones or to halt the multiplier effect in existing industrial areas. The development of a major industrial complex in the Soviet Ural Mountains, deep in the interior of the country, was partially in response to the German military advance in 1941.

A problem common to attempted industrialization of poverty’s region is multiplier leakage. Capital is invested in the economically depressed areas, but most of the profit tend to flow back to the dominant industrial areas actually increases rather than decreases.

Local and state governments are often directly involved in efforts to influence industrial locations. Actions by such governments sometimes take the form of tax concessions, such as those granted by a number of state countries, and cities in the United States.

Another type of government influence comes in the form of tariffs, import- export quotas, political obstacles to the free movement of labor and capital, and various types of hindrance to transportation across borders. But equally pronounced are the effects of industry on culture. Indeed, industrialization is the most potent and effective agent of cultural changes over to operate. Entire cultures have been reshaped as a consequence of the industrial revolution. Traditions thousands of years old have been discarded almost overnight with the process of spreading industrialization went the most concentrated burst of invention in history. Changes brought by industrialization include increased interregional trade and intercultural contact, basic alterations in employment patterns, a shift from rural to urban residence for vast numbers of people, the release of women from the home, greatly increased individual mobility and mass migrations of people; a decline in the role of organized religion, the decline of multigenerational family, greatly increased educational opportunities for the non-wealthy, and an increase of government influence and functions.

The large-scale expansion of interregional trade is largely due to industrialization, for no industrial region is self-sufficient. Each must rely on their regions for raw materials, food stuffs, laborers, and markets. Such trade contacts, often between peoples with very different cultural heritages and social patterns, naturally accelerate the process of cultural diffusion.

Before the industrial revolution, education was a luxury available only to the wealthy. In a society, however, worker productivity is closely related to the educational level of the labor force. As a rule, people strongly resist substantial changes in their basic cultural patterns unless some immediate and great personal benefit is perceived.

The industrial landscape is part of our daily life. It is a landscape not normally designed for beauty, charm, or aesthetic appeal, but rather for utility.

The manufacturing landscapes of secondary industry are most notable in the form of factory buildings. Some of these are imaginatively designed and well landscaped, others are less appealing and surrounded by grey seas parking lot. They range from the futuristic, harsh, solid geometry or chemical refineries and formless, stark “brick-pile” factories to award – winning structures designed by famous architects.

The tertiary landscape is quite varied. Its visual content includes elements as diverse of high- rise bank buildings, hamburger stands, and the concrete and steel webs of highways and railroads. Industrialization has even changed the way we view the landscape.

There are areas where such industrial landscapes are overwhelmingly dominant. But the imprint remains rather local, reflecting the highly centralized nature of industrial activity. It is possible, even in industrial districts such as Ruhr region of the West Germany, to find rural scenes and functioning farms.

To sum it all up, one of the most significant events of our age is the spread of industrialization. This has brought to a host of far reaching cultural changes. Already the industrial revolution has modified the cultures and landscapes of some lands so greatly that people who lived there a century ago would be completely bewildered by the modern setting. We traced the spread of the innovations that made up the industrial revolution, following the routes of diffusion from Britain to the rest of the world. The result of this diffusion can be graphically portrayed using industrial culture areas. The relationship between industry and the land are not one-sided. The environment influences industrial location. This web of forces comes under the theme of cultural ecology. Through the approach of cultural integration, we found that industry is related in countless ways to other elements of culture. In particular, industrial, industrial location is often governed by economic and political factors. The characteristics of industrial landscapes are familiar to us. Primary, secondary, and tertiary industries have different visual imprints. The transportation network of freeways, railways and bridges in the connecting web ion the industrial landscape.

Sunshine C. Mensurado and Carl V. Galido