- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

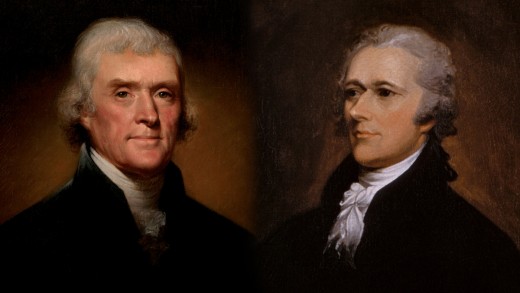

Hamilton Versus Jefferson (and the Survival of the United States)

When the Stakes were Really High

As political divisions in this country only seem to get more intense, and as we are governed by a current president who is more controversial and unorthodox than the norm, some people seem to worry that the survival of the United States as we know it is hanging in the balance. While I recognize that we are living in some pretty strange times, I do not believe that our country is on the verge of falling apart. One of the biggest political problems in the United States today is apathy. Considering how many Americans do not even care enough about politics to show up to vote, the chances of a large number of Americans taking up arms in a Revolution seem slim to say the least. Given that apathy can be a great source of stability, maybe apathy really isn’t a problem after all. Apathy may even be a sign of success.

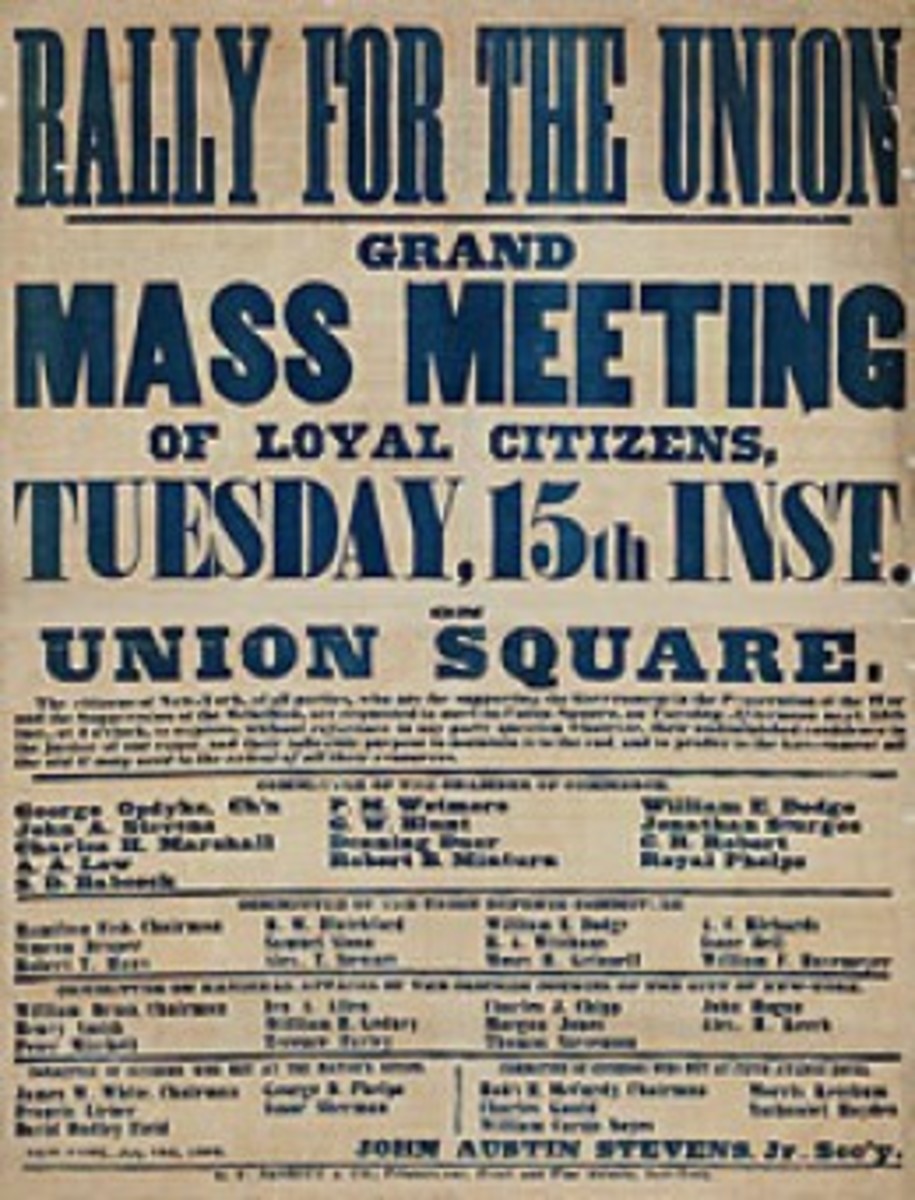

There have been a couple of times in American history, however, when the survival of our nation as a unified republic was in doubt. Needless to say, the most extreme case was during the Civil War when the United States - at least from the Southern point of view – was temporarily split into two nations. Thus far, thankfully, this was the only time in our history when Americans were willing to slaughter one another by the hundreds of thousands over political disputes. Through sheer brute force, the Union was held together, and the two sides managed to reconcile enough to avoid ever doing it again. While many people living in the former Confederacy still maintain a strong sense of identity as Southerners, only a few on the extreme fringes dream of the Old South rising again.

While there have been other times when Americans were deeply divided politically, I would argue that there was only one other period when the very survival of the nation was truly in doubt. As with any nation I imagine, things were particularly fragile at the very beginning. There were plenty of reasons to believe that the British were going to squash the self-proclaimed nation of the United States of America before it ever really started. The British seemed stronger on every level, and Americans were nowhere close to being united. At best, maybe half of Americans supported the cause of independence, with the remaining either staying loyal to the British or not taking either side. But after six years of fighting, the United States and its patriot supporters were able to convince the British that this war was not worth fighting any more.

This military victory, however, did not guarantee by any means that this new nation was going to survive. Americans who fought on the winning side (or who were neutral) did not all agree with each other about what this new nation should look like. As often happens with revolutions, this internal struggle between the winners can be as intense as the fight for independence, and these internal struggles can be far more complicated due to the large number of factions involved. It was not until the fighting was almost over that these thirteen states, long accustomed to being colonies that did their own thing, were able to settle on a system for their new national government. They settled on the Articles of Confederation, a system that gave virtually all political power to individual states. Because of an inability to raise money and do much of anything, the national government could not carry out the basic functions of any government: maintaining order, defending the homeland, settling local disputes, and enforcing basic rules so that people could do business with one another. Some people feared that this new national experiment would fail almost as soon as it began, whether it crumbled from within or if outside powers took advantage of its weakness.

It was not long before a convention was called in 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation. Instead of merely adding amendments, the men at this convention decided to create a new system of government: the Constitution that is still in place today. Today, it might seem perfectly natural that a system as well designed as the Constitution would stay intact for well over 200 years. This was the Constitution for God’s sake. The national government would now have real power, and all of those checks and balances between different branches would ensure that no single individual could dominate. But at the time that the Constitution was established, no one was quite sure how this thing might play out. The country was in debt, many Americans felt more allegiance to their states than to the nation as a whole, and external threats (like their old friend the British) were still out there. All they had was a general plan. Individual leaders with varying points of view had to work out the details.

Alexander Hamilton played a significant role in the development of the Constitution, in helping to get it ratified, and in first putting it into action. His writing of about half of the essays that became known as the Federalist Papers and his service as the first Secretary of the Treasury were the culmination of a highly unlikely life story and political career. As Washington’s right hand man during the Revolutionary War, and a man who wrote a huge amount on virtually every political issue of the day, Hamilton was an obvious choice to be the first President’s Treasury Secretary. Hamilton then quickly proceeded to become a virtual co-president, laying out the financial foundations of this new government and the country in general. This included developing a way to pay off the nation’s debts - which included tariffs and an excise tax on whiskey - a national bank, and efforts to promote manufacturing.

Hamilton’s primary goals were to establish order in the country and to move the new country in the direction of becoming a great industrial and commercial power. To make this happen, he knew that he needed a well-funded, respected national government that could lay down consistent rules and regulations that were followed nationwide. The last thing he wanted was for the government to drift back to the days of the Articles of Confederation and its chaotic system of basically sovereign states. His fears of where disorder could lead were confirmed when the French Revolution broke out in the late 1780s and grew increasingly chaotic and bloody. While he believed in representative government, he was also convinced that a strong national government was needed to keep people in line. Too much liberty could lead to anarchy.

While Hamilton was clearly the dominant figure in George Washington’s first Presidential administration, Washington also hired another man who would come to be tremendously powerful and influential. While Hamilton was making a name for himself during the years that led up to the Constitution, Thomas Jefferson was serving as ambassador to France. This foreign policy experience, along with his careers as a revolutionary, politician at the state and federal level, and plantation owner, made him an obvious choice as the first Secretary of State. The only problem was that Thomas Jefferson disagreed with Hamilton, Washington’s right hand man, about almost everything.

Because he was in France, Jefferson was not involved in the writing and ratification of the Constitution. When he eventually decided to take the job as Secretary of State, he already had some strong misgivings about this new government. Jefferson preferred a government more like the Articles of Confederation in which the states maintained most of the power. He feared that a strong national government could become tyrannical, just as the British had become in the years leading up to the Revolution. He also wanted the nation to stay primarily a land of independent farmers, not a country of merchants and shopkeepers. In his mind, only a nation of landowners could stay a true republic. When people no longer own land, they will eventually be controlled by someone else. Jefferson the plantation owner – and, ironically enough, the slave owner – was more concerned about liberty and the rights of the everyday American than about disorder and anarchy.

When the French Revolution broke out, Jefferson predictably had a different reaction than Hamilton. He openly rejoiced that the land he had lived in for years was going through the same process as the United States, with freedom and liberty on the march around the world. Even when things started to turn ugly and bloody, Jefferson continued to insist for years that things were not as bad as some were reporting and that liberty would ultimately prevail. Eventually, he was forced to admit that things had not turned out as he had hoped. But even when France was taken over by Napoleon and was fighting virtually everyone in Europe, Jefferson tended to favor France over Great Britain. Hamilton, on the other hand, tended to see the British as the proper role model.

With these two men, who disagreed about almost everything, working in the same administration, it was not long before conflict arose. As a general rule, Washington supported Hamilton as his Treasury Secretary implemented his financial program. Hamilton was also an almost superhuman work machine intricately involved in virtually every aspect of setting up the new government. Through proxies, the increasingly resentful and horrified Jefferson attacked Hamilton in the press, claiming he was a man driven by ambition who planned to move the United States toward monarchy. He also personally voiced his concerns directly to Washington on many occasions and tried to get the President to get rid of Hamilton. Ultimately, a frustrated Jefferson would be the one who resigned near the end of Washington's first term. He would then continue to work behind the scenes leading the opposition to the Federalists, and he would eventually step up to become the nation's third president.

Hamilton, who had never been a person who would shy away from a fight or tolerate attacks on his honor and integrity, attacked back (often using surnames) in newspapers sympathetic to his point of view. Even after he resigned his post in early 1795, Hamilton continued to take on all opponents and immerse himself into the political debates of the day. Partisan politics was being born, with the Hamiltonians eventually taking the label of Federalists and the Jeffersonians generally referred to as Republicans. From the start, the partisan attacks on both sides could be as exaggerated, personal, and vicious as anything found on the internet today. In those days, newspapers did not even pretend to be objective.

It is tempting to look back at men like Hamilton, Jefferson, and other prominent leaders of the era as typical politicians driven by their ambition and their egos. For people today, the issues that they were arguing about might not seem like that big of a deal, and when it came down to governing, the policies of President Jefferson were not all that different from those of Washington or (the Federalist) John Adams. Much of the financial program created by Hamilton stayed intact when his opponents Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe each served two terms in office.

Although some of the intense divisions of the time can be written off as typical partisan politics, it is important to not downplay the profound aspirations and fears that helped explain the level of intensity. For good reason, people were afraid that this brand new nation, this noble republican experiment in a world dominated by dictators, might not survive. They had visions of what they thought this new nation should be, and they believed that people on the other side had a flawed vision that threatened to drag the whole thing down. And no matter what direction the nation might take in those early days, they knew that it would be extremely difficult for people of the future to slow the momentum and take the country down a new path. For every decision those early leaders made, the stakes seemed extremely high.

Of course, the nation didn't fall apart. Instead, it ultimately grew and thrived. It is hard to say exactly why the country managed to hold together. The Constitution created a far more functional central government than the Articles of Confederation. As even his opponents had to admit (grudgingly), Hamilton's financial program seemed to put the country on a more stable footing. But the early United States may have also benefited from luck. Europe was at war for much of the first twenty-five years or so of American history, which kept many powerful nations distracted as the United States was taking its first baby steps. Conflict in Europe also created the opportunity to acquire a huge amount of land when Napoleon offered the entire Louisiana territory to the United States in 1803. Without the wars in Europe, Napoleon would have never taken the land from Spain and would not have needed the money to keep financing these wars.

Fortunately, the United States was wise enough to not take sides officially in the European conflict, much to the chagrin of France who had helped out during the American Revolution. Unfortunately, neither the French nor the British respected American neutrality, with both interfering with American ships that were attempting to trade with both sides. The British engaged in this practice more, which was the main factor in the United States' eventual decision to go to war with the British (once again) in the War of 1812. But this war proved to be another case of the United States benefiting from years of European conflict. Because the British were at first distracted by its continuing fight with Napoleon and were worn down by years of conflict, the United States was able to fight the British (more or less) to a draw. And at this point in history, a draw for the United States was basically a victory. If nothing else, this war proved that the United States had some capacity to put up a fight, and it was another step toward the United States becoming a little bit more of a union rather than just a collection of states.

The War of 1812 also had another impact on the United States. It essentially ended what was left of the original two party system. Federalists (centered in New England), who had been the weaker party for a while, decided to come out in opposition to the war. But then the war ended fairly well for the United States with victories at Baltimore and New Orleans, so many Americans viewed Federalist opposition to this now popular war as stupidity, cowardice, or even treason. The Federalist Party was now dead, and the next 15 years were known as the "Era of Good Feelings" because two-party partisan politics seemed to have gone away. Then Andrew Jackson came along, and his supporters began calling themselves Democrats - although, ironically enough, he was carrying on the Jeffersonian Republican tradition - and his opponents became known as the Whig Party. Although the Founding Fathers had not been big fans of political parties, the two party system seems to be an inevitable feature of the American political process.

Hamilton, the original Federalist, had left the scene many years before. Never able to walk away from a fight or a challenge to his honor, he got himself killed in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804. Jefferson, on the other hand, served two terms as president and lived to see the 50th birthday of the United States. On the surface, it seems that Jefferson's Republicans won as they dominated the elections for three decades. But in the battle of ideas, a strong case can be made that Hamilton won. His vision of a strong national government and an industrial economy, after all, clearly won out over the long haul.

While Hamilton would likely be happier than Jefferson with how the nation has turned out, I imagine that both men would have been pleasantly surprised that the United States is getting close to its 250th birthday. The United States did not only manage to hold together. It has long been a military and economic powerhouse. Although so many things about the United States today would be completely foreign to them, the nasty partisan politics of modern America would seem quite familiar. If anything, they might even conclude that the attacks have toned town a bit, and the stakes in this political competition are not as high, as in the days when the country was just getting off the ground. Having lasted now for almost a quarter of a millennium, most Americans cannot imagine a world without the United States in it.

Hamilton would also be happy that he is currently a Broadway star, and a whole generation of young people is being brought up to think he was a hero. This current adulation of Hamilton, however, might not last. At other times in our past, particularly during bad economic times when people were angry at big businesses or banks, Jefferson was viewed as the more heroic figure. Jefferson's many statements about protecting liberty also tend to make better memes on the internet than the more pragmatic writings of Hamilton. The fact that Jefferson was a slave owner and Hamilton was strongly anti-slavery has not stopped many Americans throughout our history from viewing Jefferson as the nobler fighter for freedom and democracy.

I suppose that their rivalry has never entirely ended. We still argue about the proper role of the federal government, tax policies, and the type of economy we should be. Some people even think that our answers to these basic political questions could determine whether the United States continues to thrive or goes into decline. But unlike Hamilton and Jefferson's day, the people who truly believe that the nation's survival is at stake are on the political fringes. When politicians today claim that the other party is going to destroy America, I think they know that they are just using fear to get votes. While Hamilton and Jefferson also knew how to manipulate public opinion, they actually believed for good reason that our survival was at stake.