- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Hired Guns: The Early Arizona Peace Officer As Agent of the Existing Power Structure

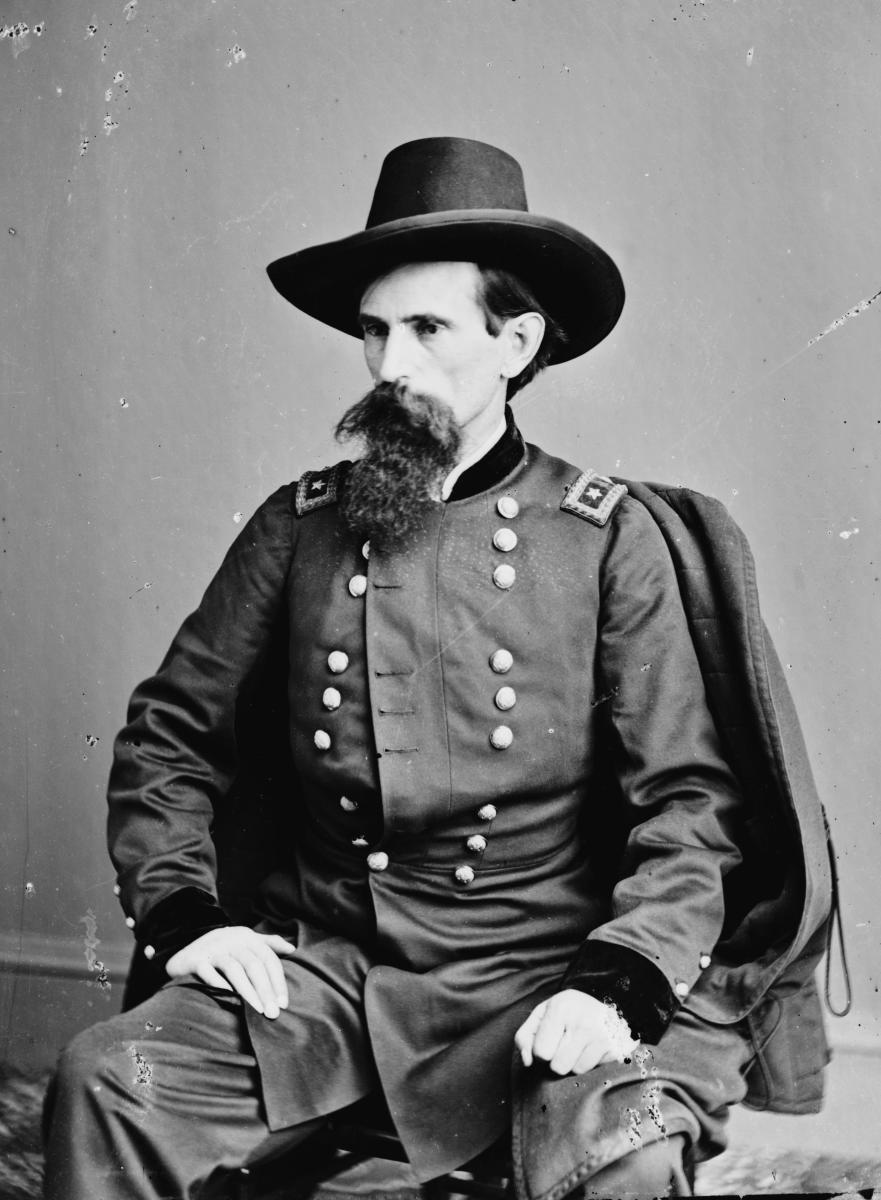

Meet Arizona Ranger Captain, Harry Wheeler

In many ways, Harry Wheeler exemplified the western peace officer romanticized by books and film. He was perhaps more stereotypical than typical of his profession: a courageous veteran gunfighter, he was a skillful marksman. An Arizona Ranger who rose from the ranks to be captain, he was later elected sheriff of the rugged, violent Cochise County. He endured scandal while in office, served in the United States Cavalry, and died a drifter. And, during his tenure behind a badge, he sometimes engaged in controversial and unethical activity that supported the commercial interests of the community's existing power structure rather than honoring the law or protecting the rights and safety of the public. Law enforcement officials frequently served as reliable servants of interest groups, be they the Church of Latter-Day Saints, the mining companies, the railroads, the cattle outfits, or the white upper classes. Harry Wheeler's special relationship was with the mining companies that dominated southern Arizona.

Bisbee, Cochise County, Arizona

Sheriff Wheeler and the Bisbee Deportation

By July, 1917, Henry Cornwall Wheeler had already served several years as Sheriff in the desert county in the state's south-eastern corner. His career had been distinguished by honor and talent and, for a man in his early 40's, he'd had many impressive achievements. He was known to be a just and honest man. Yet his actions in what became known as "The Bisbee Deportation" tainted his reputation and resulted in his eventual indictment (although not conviction).

Bisbee, a mining town in the Mule Mountains, struggled with racial tension as did most western towns. Bordering Mexico, and occupying land that had belonged to Mexico prior to the 1854 Gadsden Purchase, Bisbee had a large Mexican population. In 1917, the mine workers engaged in a large-scale strike. The conditions precipitating the strike (and the Deportation) were convoluted, involving ethnic alliances, unsafe mining conditions, differential wages, support for the country's entrance in World War I, and the presence of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Union. It is a gross oversimplification to say that striking miners were the cause of the deportation; however, the strike doubtless served as the flint to ignite the social tinderbox that was Bisbee.

In the heat of mid-July, with the assistance of 275 deputized citizens, Wheeler forced approximately 1,187 people onto filthy cattle cars at the railroad station. The detainees, who were IWW agitators ("Wobblies") and workers at the Copper Queen Mine, were primarily Mexican immigrants. The illegally-imprisoned miners were taken about a hundred miles away into New Mexico and freed. Fortunately, the United States Army came to their rescue -- and to Wheeler's, in a way. It was through the Army that Wheeler left Bisbee but months after the Deportation. Highly patriotic, he re-enlistsed and attempted to serve in World War I. However, prior to seeing combat he was recalled from France to Arizona to answer charges resulting from the Deportation in court.

As a side note, Wheeler's support of the war has been suspected as a possible motive for his vendetta against the strikers; he viewed them as keeping copper from the war effort.

Arizona Rangers to the Rescue -- of the Owner of a Mexican Mine, That Is.

The small company of men known as the Arizona Rangers had, during Wheeler's earlier service with them, also been used for political purposes on many occasions. In 1906, Rangers crossed the border to assist Colonel William Greene, an American owner of a large mine in La Cananea, Sonora. In a situation that foreshadowed today's las maquiladoras, Greene exploited the cheap, easily oppressed Mexican laborers at his Cananea Consolidated Copper Company. When the miners rioted, Greene requested the assistance of the Rangers. While serving as Arizona peace officers, the responding force (comprised of Arizona Rangers, under the command of Captain Tom Rynning, and two Bisbee constables) was sworn in as officers in the Rurales, a Mexican law-enforcement force. The swift, sure response to the strike included the execution of many Mexican strike-leaders. Their bodies were lined up, arms crossed over their chests, for other miners to see.

Arizona Rangers Arresting Foreign Anarchists

Rangers responded to an even more overtly political border situation in September of the same year, and this time at the behest of Arizona Governor Kibbey -- the same Governor who questioned the Rangers' actions in Mexico in La Cananea. In Douglas, Rangers arrested Mexican citizens plotting revolutionary activities against Mexico's president Porfirio Diaz. The next day, Rangers arrested more revolutionaries in Patagonia and the now-ghost-town Mowry. The arrest of foreign anarchists (not guilty of crimes against the United States government) certainly seems to be outside the scope of an American civilian law enforcement officer.

Lawmen on Both Sides of the Law

The role of the peace officer as an agent for the commercially or socially powerful was a common one, although Wheeler's Bisbee story is unique in its magnitude. In Arizona, as both a territory and a new state, the lines separating vigilantes, professional law enforcement, mercenaries and hired thugs for commercial enterprises were often smudged and indistinct. Men moved easily between careers as criminals and careers as peace officers, their reputations often enhanced, rather than tarnished, by their colorful and violent histories. Today, minor criminal offenses of any nature can forever preclude a candidate's career in law enforcement; in the late 19th and early 20th century, serious (and repeat) felonies were of little consequence to future or current peace officers. No POST (Peace Officer Standards and Training) Board exited; no background checks were performed; no special training or certification was required of most law enforcement officers. Then, as now, the profession required flexibility, courage, and specific physical skills and abilities.

The Western Peace Officer: Support of the Status Quo

The existing power structure has historically had an enforcement branch of varying degrees of formality to maintain the status quo and keep the labor force in its place. Arizona followed a long Anglo-Saxon tradition of using armed men to keep the working class and minorities subdued. Old systems of approved vigilantism -- such as the responsibility of European villagers to raise the "hue and cry" to track down and apprehend criminals or those who disturbed the peace -- evolved into the office of the sheriff, a position of significant standing in the community. In the territories, vigilantes stepped in where legitimate law enforcement was unavailable, or where the citizen believed it was ineffective or unresponsive to their wishes.

Sheriffs vs. Mob Mentality

The county sheriff has the responsibility of maintaining detention facilities (jails). As custodians of prisoners, sheriffs were directly exposed to the threat of lynch mobs. The manner the sheriffs handled the threat varied. Some sheriffs passively complied with the wishes of the mob by leaving the jail unattended, occasionally even taking other, uninvolved detainees to a safer place. Others made a token stand against the mob, then relinquished the doomed prisoner they were charged with safeguarding. Sheriffs who took this duty seriously transported the prisoner to safer ground, or hid them locally until the threat subsided; and some, distinguished by their courage and honor, stood against the mob. Some deputies, incensed at their sheriff's unwillingness to defend his prisoners, resigned in disgust. More than fifty people were lynched by mobs in territorial Arizona.

Descriptions of lynching often cite the presence and involvement of "upstanding citizens" and powerful members of society at these events. I suspect the sheriffs who failed to protect their prisoners were influenced to some degree by the endorsement of the town's leaders and businessmen. Standing passively by or, as in some instances, leaving town when rumblings of a mob plot became known, supports the argument that sheriffs were often more interested in supporting the power structure of the community rather than maintaining order, enforcing the law, and keeping the peace. A strike by a largely-Hispanic labor force was dealt with severely and violently; a mob overtaking a county facility, intent on murder and clearly disrupting the peace, was all-too-often allowed to reach its cruel conclusion.

Mob activity occasionally included the duly-appointed peace officer himself. In the 1904 Clifton-Morenci orphan abduction, sworn deputies actively participated in removing the children from the homes of their would-be adopters. The children were placed in the homes of the towns' ruling class, the wealthy whites. The deputies' involvement clearly served to protect the existing social structure and effectively maintained the segregation and exclusion of the minority labor class.

Private Police: Pinkertons and Other Investigators

Differing from vigilantism but nonetheless providing a means of protecting the big interest groups were various corps of quasi-law-enforcement officers such as the Pinkertons and other private detectives. Former and future duly-appointed law enforcement officers slipped in and out of these private police forces with regularity. In addition to funding campaigns of local sheriffs, railroads, mining firms and cattlemen's associations hired forces of their own. The infamous Tom Horn, a sometime-deputy, range detective and Pinkerton man, was well known to be a paid assassin of various firms and individuals. Often the "foreman" of a cattle outfit was responsible primarily for apprehending and / or killing rustlers. Burt Mossman, the first captain of the Arizona Rangers, was a veteran Hash Knife superintendent. Commodore Perry Owens (Commodore being his first name, not a title), for three years the sheriff of Apache County, later served as detective for the Santa Fe Railroad.

The Pinkertons were a highly-effective protective force, but used highly-illegal methods of investigation and apprehension to obtain this effectiveness. They served as strikebreakers and violent henchmen for large and powerful firms. Pinkertons, like other private police, often worked cooperatively with appointed peace officers. Private detectives were better paid than were appointed peace officers (although sheriffs themselves often made a substantial income). The money necessary to pay for range protection and asset security was plainly only within reach of the interest groups and powerful commercial firms.

So threatening did private detectives and their methods become to the working class that many states, Arizona among them, enacted legislation to prevent companies from bringing in armed forces to prevent "domestic violence" (not to be confused with today's definition of domestic violence) or for the suppression of labor unrest.

Politics, Politics, Politics.

Historian and author Richard Frank Prassel, in his outstanding book "The Western Peace Officer," sums it up well: "A key element to interpreting county law enforcement in the West, and one which cannot be underestimated, constitutes a continuing plague to proper police work -- politics. Despite misleading appearances, peace officers seldom embody true social power instead, they normally represent the interests of community wealth and authority." Then, as now, elected officials were prone to pandering to influential individuals and interest groups.

Certainly a significant factor contributing to the fealty sheriffs such as Harry Wheeler gave to the most powerful citizens and businesses is the political nature of the position itself. Then as now, sheriffs were elected officials in the West, and as such constantly aware of the need to please their powerful supporters. Adding to this was the short term of office (initially one, then increased to two years) then in place for sheriffs. Re-election was inevitably always in mind. The position of sheriff itself was a common springboard for future political success, and many of Arizona's highest offices have been held by former sheriffs.

Commercial enterprises financed candidates' campaigns and encouraged employees to vote for the preferred candidates, who were often known to belong to the railroads, mining companies, or cattle outfits. As public sentiment turned against the businesses, savvy politicians campaigned by coming out against the appropriate enterprise; Yavapai County's famed Buckey O'Neill, for example, ran an "anti-establishment" campaign in which he promised to hold railroad and mining companies accountable.

Other components of the judicial system enhanced the power that interest groups had, as well. A judge who acquits a defendant based on preferential treatment (or, conversely, convicts on same) not only impacts the individual defendant, but the decisions of law enforcement officers and their governing policies. Departments today will not submit certain cases based on the charging policies of the county attorney's office, despite the substance to the case itself; most certainly, similar factors played into line-level application of the law throughout the history of the state.

Pawns of the Powerful

Common themes surface in the discussion of old Arizona law enforcement as the agents of the power structure: affiliation with private police forces; alliances with industry; racism; vigilantism. The power groups of early Arizona -- big industry, politicians, cattle barons, influential and affluent citizens, the dominant ethnic class, and mobs -- placed undue influence and administrative and financial control on the community's law enforcement system. Harry Wheeler, who by some accounts was a broken and dishonored man when he died in Bisbee in 1925, felt the burden of that influence. Many individuals in the lower social strata -- miners and Mexican laborers, for starters -- bore the burden of law enforcement's service as the pawns of the powerful.

Copyright © 2014 MJ Miller

All rights reserved. No part of this article (including photographs) may, in whole or in part, be reproduced without the express permission of the author. Links to this page, however, may be freely shared. Thank you for pinning, sharing, liking, +1'ing, forwarding and otherwise helping me grow my readership. Most of all, thanks for reading!