His Truth Is Marching on: John Brown

Introduction

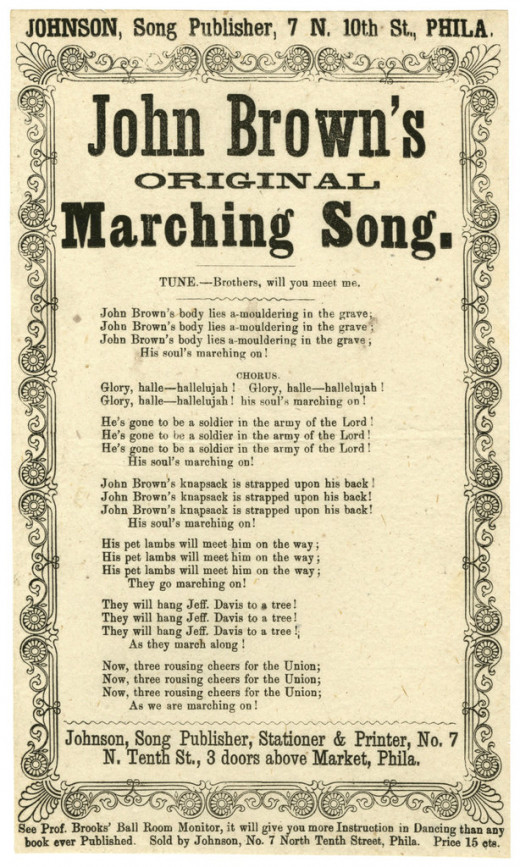

At eight o' clock A.M., October 16, 1859, fifty-nine year old John Brown and eighteen of his twenty-one followers started on their way from the Kennedy farmhouse in Virginia, where Brown had been staying throughout the summer and fall, to Harper's Ferry, with the general intentions of provoking an uprising of slaves and other oppressed southerners to defeat all opposing forces and abolish slavery; first in Virginia, followed by North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, and eventually in every state where slavery was legal. Brown anticipated that his army would not be met with any major resistance by opposing forces until it had grown large enough to suppress any opposition it was faced with. Three men were left behind to move the supplies Brown had accumulated, which included one hundred and ninety-eight Sharps rifles and nine hundred and fifty pikes, to another location where they could arm the slaves and others who they felt would surely join the fight.

Brown's band met no resistance upon entering the town and quickly seized the United States armory, arsenal, and rifle works; three strategic points he had planned well in advance to take possession of. Taking possession of these points put several million dollars' worth of arms and munitions into Brown's hands. It also gave him his first hostages of the raid, for he took as prisoners the watchmen who had been put in charge of guarding these buildings.

The next step by Brown's crew was to begin rounding up hostages from outside of town, and begin informing the slaves they had been liberated. Brown had made preparations in advance for this step. He had sent John Cook, one of his most trustworthy followers, to investigate the plantations in the surrounding area several months before he planned to raid the town. Cook provided him with information regarding the plantation owners, and their slaves, so that Brown would know exactly which plantations to seize first. Six of his men were sent out of town to begin taking plantation owners as prisoners and informing the slaves they were free. Lewis Washington was the first plantation owner to be taken prisoner; his carriage, wagon, horses, and four of his slaves, were taken from his plantation by Brown's crew to help support the raid. John Allstadt, and his son were the next to be taken from their beds as prisoners. Six of Allstadt's slaves were taken to the arsenal, handed pikes by Brown's men, and ordered to guard Allstadt and Washington. Between thirty and forty townsmen, mostly employees at the arsenal, were also taken as hostages by Brown's crew.

Everything, thus far, had gone just as Brown had planned. Unfortunately for Brown, around five o' clock A.M., the following day, a foolish mistake was made by some of his men. The Baltimore Express, which was passing through Harper's Ferry, was stopped by several of his followers, who eventually allowed it to push on, leaving passengers suspicious that a raid was occurring. Carrying news to nearby towns about the raid they suspected, it wasn't long after this incident that Brown and his men were surrounded by angry farmers carrying firearms. Trapped in the engine house of the arsenal, along with their hostages and the slaves they had taken from plantations, all Brown and his crew could do at that point was hope for a truce. Despite a couple of attempts by Brown to negotiate with his enemies, no agreement was ever reached. By October 18, a group of marines entered Harper's Ferry with orders from President Buchanan to suppress the raid. Despite sever resistance by Brown and his men, the marines were able to break down the door of the engine house and end the invasion, as they had been ordered to do.

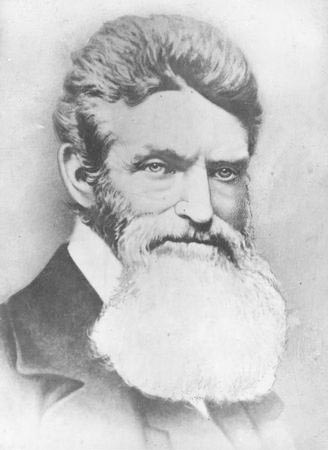

Less than two days after it had started Brown's desperate attempt to end slavery had been utterly defeated. Ten of his crew had been killed or fatally injured, five were taken prisoners, and the rest had escaped, some temporarily, and some for good. As for Brown, severely wounded after being struck with a dress sword by one of the marines, he was arrested and sent to jail, and on November 1, 1859, after a lengthy trial, he was executed for treason.

This invasion Brown led at Harper's Ferry has caused a great deal of controversy amongst scholars and historians. Ambiguities concerning Brown's competence at the time of the invasion, uncertainties concerning his true motives, and contradicting testimony by Brown and other involved parties before and after the invasion are among the reasons why many authors have had distinctive views concerning this event.

One of the biggest issues concerning this event that many historians of the past have had opposing views on was whether or not Brown was insane at the time he invaded Harper's Ferry. A number of historians, such as James Schoular and Allen Nevins, believed evidence suggesting Brown was mentally incompetent, at least in issues involving slavery, was sufficient enough to conclude that insanity played a major role in Brown's invasion? Historians, like Schoular, who have supported this claim, havepointed to evidence from Brown's trial that suggested his incompetence, and hardships he suffered throughout his life which could easily have driven the man insane; especially hardships he suffered during his involvement in the Kansas crisis during the mid-1850's.

There have also been a number of historians who have rejected the insanity explanation, claiming evidence did not support such a conclusion. For example, C. Vann Woodward argued in, "John Brown's Private War," that many Americans during Brown's time suffered hardships similar to those suffered by Brown, and that evidence from Brown's trial suggesting he was insane was unreliable and had been distorted by politicians. Furthermore, he argued that the records suggesting Brown's insanity during his trial were from parties that could easily have mistaken insanity for a number of other diseases. He supported this argument with evidence suggesting that at the time Brown led the invasion at Harper's Ferry, there was not an adequate enough understanding of mental diseases for anyone to have concluded he was insane.

Stephen B. Oates, in his elaborate biography on Brown, To Purge This Land With Blood, also argued that Brown was not insane. Like Vann Woodward, Oates also considered the records from Brown's trial suggesting Brown's insanity as unreliable. He argued that because these records were mostly based on here-say, and were not based on real clinical evidence, there was no way they could have been considered reliable evidence suggesting Brown was insane. Furthermore, he stated that the authors who have considered Brown insane, have ignored the sympathy Brown felt for the suffering of the slaves.

Another issue concerning the invasion at Harper's Ferry that has left many historians in disagreement involved the distance Brown was planning to go. A number of historians, mostly from before 1950, such as Oswald Garrison, believed Brown planned to only make a sudden raid at Harper's Ferry from which he hoped to immediately retreat into the mountains. Villard believed Brown's intentions were not to provoke a massive slave uprising in Harper's Ferry, starting a chain reaction of uprisings in every southern state, ultimately ending with the abolition of slavery, as most subsequent historians believed. Rather, he felt Brown was fed up with the traditional peaceful means that were being attempted to end slavery, and wanted only to set a precedent of forceful means for ending slavery, hoping anti-slavery forces would follow his precedent and begin fighting slavery using violence, as opposed to peace. Furthermore, Villard believed Brown could not have planned a massive slave uprising, because if he had, he would not have chosen Harper's Ferry as the place to invade, since Harper's Ferry, claimed Villard, did not have an abundance of slaves or abolitionists.

Most recent historians; however, such as Allen Nevins, have rejected this claim, saying Brown did plan a full-scale uprising in Harper's Ferry. Nevins, in his article, "John Brown at Harper's Ferry," was the first historian to develop a very convincing argument suggesting that it certainly was a full-scale uprising that Brown had intended through his invasion. In providing a detailed description of the two days during which Brown held Harper's Ferry, he believed that the evidence regarding these two days clearly suggested that Brown was planning an insurrection. For example, he was convinced that evidence regarding the raid revealed that Brown was not planning to retreat from Harper's Ferry; thus, claimed Nevins, he must have been planning to win a victory there and move on to another location.

Although, several historians, such as Barrie Stavis, have disagreed with Nevins's argument that Brown was not planning to retreat from Harper's Ferry, ever since Nevins's article was published in 1950, it had been common for authors to agree with him that Brown certainly was planning a full-scale insurrection, for far to much evidence available today, such as letters, interviews, and testimony, implies that Brown was planning nothing less than the complete abolition of slavery through his raid.

One other major issue that has led to conflicting views amongst historians involved Brown's true motives for his invasion at Harper's Ferry. In this area, many authors have shown their true biases concerning their views on this event. For example, Hills Peebles Wilson in, John Brown, Soldier of Fortune: A Critique, claimed that Brown was motivated with the hopes of gaining money and fame through his achievements in abolishing slavery. He claimed that the Harper's Ferry invasion was just a desperate attempt by Brown to gain fortunes. Several subsequent historians, such as Oates, believed that Wilson, and several other authors who had similar views as Wilson, were biased in their research, for, claimed Oates, they failed to review portions of evidence refuting the claim that Brown was a criminal. Not being a criminal, argued Oates, repudiates the possibility that Brown invaded Harper's Ferry only to get rich.

Other arguments by historians regarding Brown's motives included Villard's claim, that it was Brown's strong devotion to Christianity that motivated him to consider such an invasion. According to Villard, Brown truly believed he was on a mission from God to end slavery, and was prepared to resort to any means necessary to accomplish this mission." Still other historians, such as Benjamin Quarles, have claimed that it was more Brown's true devotion to ending slavery that motivated him to attempt such an invasion. Quarles emphasized Brown's long commitment to the abolition of slavery and his long period of maintaining close relations with African-Americans. He also argued that Brown resorted to arms, because to him, slavery was itself a species of warfare.

Based on the evidence regarding Brown's life, I'm convinced that Quarles was accurate in arguing that Brown's long commitment to the abolition of slavery was his main motive for invading Harper's Ferry. However, evidence other that that indicating Brown's close relations with African-Americans has led me to this conclusion. For example, evidence revealing Brown's characteristics suggests that it was possible, given the right characteristics and environmental background, for an antebellum white northerner, like Brown, to be so devoted to ending slavery that he would engage in a dangerous and, to some extents, desperate attempt, such as the Harper's Ferry invasion, to coerce the emancipation of the slaves. Also, evidence suggesting he was not insane; nor was he a thief interested in fame and fortune, suggests that his desire to liberate the slaves was the only reasonable motive he could have had for leading the raid.

In this work, I will also attempt to prove that Brown had been contemplating a plan to free the slaves for a longer portion of his life than had been suggested by most previous authors. Throughout many experiences in his life, such as surveying land in Virginia in 1840, and fighting to keep Kansas a free state in the mid-1850's, his desire to liberate the slaves was on his mind; thus, when it came time for him to enforce his plan to end slavery, it had evolved into a rather intelligent plot, which could very well have succeeded had it not been suppressed by opposing forces sooner than he had anticipated. This long period of time during which his plan evolved, to me, clearly reflected his true desire to liberate the slaves, for it suggests he was not insane; nor was he thief. Rather, as Quarles argued, it suggests that his only motive in invading Harper's Ferry was to witness an institution he considered evil and immoral become abolished.

Chapter One: Was He a Dedicated Enough Abolitionist to Invade Harper's Ferry Only for the Purpose of Freeing Slaves?

If any Euro-American from the Antebellum north was capable of developing a plan to abolish the institution of slavery by invading a region in the south and following through with it entirely, it was John Brown. Brown developed all the characteristics one would need to be capable of planning and pursuing such a plot, only for the purpose of seeing slavery become abolished. Characteristics such as an extreme opposition to the oppression enslaved blacks were subject too, the belief in equality between blacks and whites, the belief that slavery was a sin against God, the willingness to give his life in pursuit of ending slavery, and the devotion to always follow through with his plans, no matter how unlikely it was they would succeed, all made it possible for a white man from the north to invade a region in the south in the hopes of abolishing slavery without any other motive other than the desire to suppress an institution he felt was evil and immoral. Developing characteristics such as these sent Brown well on his way to becoming the first white northerner to experiment with violent means in attempt to abolish slavery.

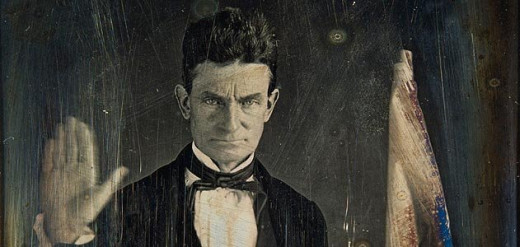

Being taught to oppose slavery was one characteristic that contributed to Brown's motives to invade Harper's Ferry. Like most other northerners, Brown learned to oppose slavery early in life. He was born in 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut, to a family with a history of being "firmly opposed to slavery."' His father, Owen, "ran a station in the underground- railroad" and had a secret place right on his premises "for hiding runaway slaves as they were passed from station to station northward to freedom. "Being the child of a man so opposed to slavery, Brown himself began learning to oppose slavery while he was still very young, mostly by listening to the lectures of his father. Through his father's lectures, Brown, his sister Anna, and the other children from the Brown family learned "not to hate Negroes but to be kind to them and oppose their enslavement as a sin against God."

Brown's piety also contributed to the motives that drove him to invade Harper's Ferry. Piety was a characteristic he also developed at a young age. His parents made an oath, shortly before he was born, to teach their children to be firm in their Calvinist religion. By following through with their oath, Brown was taught to read the Bible, to attend church regularly, and above all, to obey God's commandments.

By heeding the teachings of his parents, Brown became very pious going into his adulthood. Frequent prayers, intensive studies of the Bible, and resembling Christ through his actions, were among the ways he expressed this characteristic.

Frequent praying was one way he expressed his piety. During the 1820's, when he was miming a tannery in Randolph, one of his employers confirmed how important Brown considered praying. He stated that Brown required everyone to pray and read verses from the Bible every day prior to breakfast and dinner. About thirty years later, according to James Redpath, who had spent an evening with Brown and his men in Kansas in 1856, Brown still considered praying before meals important. Redpath stated that Brown ensured his men were all united in prayer every morning and evening before and after meals were served?

Another way he expressed his piety was by resembling Christ through his actions. One of the ways he resembled Christ was by allowing himself to suffer so that the sins of other individuals could be forgiven, the same way Christ suffered so that the sins of his children could be forgiven. A good example in which Brown resembled Christ in this manner was illustrated by his son, John Brown, Jr. John Brown, Jr. wrote that as a child, it was customary for him to receive whippings after committing a sin. On one occasion, however, after he had committed a sin, his father handled it in a whole different manner. "We went into the upper finishing room," he recalled, "and after a long and tearful talk over my faults, father stripped off his shirt, and, seating himself on a block, gave me the whip and bade me lay it on' to his bare back. I dared not refuse to obey, but at first I did not strike hard. 'Harder!' he said; 'harder, harder!' until he received the balance of the account." He further stated that it was not until later that he realized his father had been consciously assuming the mantle of Christ."

Finally, Brown expressed his piety through intensive studies of the Bible. Studying the Bible allowed him eventually to become so familiar with the scriptures that he could quote any passage he wanted; especially passages from the Old Testament. According to testimony from his neighbors when he lived in Randolph, Pennsylvania, during his early twenties, he frequently quoted the Old Testament "from one end to the other" while in conversation. He also used his knowledge of the Bible as a guiding force through his life. Some of his neighbors from Randolph testified that his belief that one's life should reflect the Scriptures was so extreme that he only formed ties with neighbors who also lived according to the Bible; and he looked at neighbors whom he felt did not support the Bible with extreme suspicion.

Brown's religious values were important characteristics in explaining his motives for invading Harper's Ferry simply because, according to him, God opposed slavery. Unlike religious slaveholders, who felt the Bible provided evidence suggesting God supported slavery, Brown's interpretation of the Bible convinced him that God was opposed to the enslavement of individuals. He made this belief very clear in many letters he wrote and conversations he had with others throughout his life. For example, in a letter to F.B. Sanborn, one of his main abolitionist connections, in 1858, in regards to his "ultimate plot," he wrote that "A good cause is sure to be safe in the hands of an all-good, all-wise, and all-powerful Director and Father." Since he was referring to his plan to abolish slavery, this statement revealed how convinced he was that God opposed slavery, the same way he did.

It's important to note, however, that unlike what some scholars, such as J.C. Furnas, have claimed, Brown did not feel that because he had the support from God, he could be successful in any plan of invasion, regardless to how reasonable it was. He felt God supported his plan, but not to an extent where he believed God would make his plan succeed in the same manner he helped Moses succeed in freeing the Hebrews. Rather, as will be explained in chapter four, he was reasonable enough to develop a plan that stood a chance of succeeding, regardless of whether or not it was supported by a Higher Power.

The courage to engage in life-threatening events was a third characteristic Brown possessed that helps clarify how it was possible for a white northerner to consider invading a region of the south in the hopes of abolishing slavery. For anyone to consider engaging in an invasion as dangerous as the one Brown led in Harper's Ferry, they would have to possess an enormous amount of bravery and, according to evidence, bravery was something Brown did not fall short on. According to Charles Griffing, who helped construct the Ohio underground rail road in the 1840's, "no one would brave greater perils or incur more risks to lead a black man from slavery to freedom than he." He also stated that if Brown had to, he would have laid "down his life to help fugitives, because death for a good cause" to Brown "was glorious." In this statement, Griffing not only considered Brown the most courageous abolitionist he'd ever met, but also claimed that Brown was willing to sacrifice his life to help enslaved blacks to freedom.

Griffing was not the only person who considered Brown as courageous when it came to freeing slaves. Other people who had known Brown, such as his recruits in Kansas and prisoners he had taken during his raid at Harper's Ferry, made similar statements as Griffing's regarding Brown's devotion as an abolitionist. For example, John Dangerfield, who was taken prisoner by Brown during the Harper's Ferry raid, stated, shortly following the raid, that Brown was "as brave a man could be," believing it his duty to free the slaves, "even if in doing so he lost his own life." He also stated that he had "never seen any man display more courage and fortitude than John Brown showed under the trying circumstances in which he was placed."

Statements such as these made by Griffing and Dangerfield indicate that Brown undoubtedly had courage enough to follow through with a plan in which he stood a chance of dying, like he did in his plan to invade Harper's Ferry. Especially the statement made by Dangerfield; for if anyone could have been trusted to give accurate testimony regarding Brown's character, it would have been one of Brown's prisoners during the raid. Being a man who had no known experiences with Brown, other than his experience as Brown's prisoner, Dangerfield could have had no reason to dramatize his perception of Brown's courage.

Brown's piety and his opposition towards slavery were the two characteristics that would later become his ultimate motives for invading Harper's Ferry; and his courage allowed him to follow through with such a plan. However, being pious, courageous, and opposed to slavery alone, certainly cannot explain in full why he did what he did; for millions of other northerners during his days were undoubtedly pious, courageous, and opposed to slavery as well. There was one other characteristic he developed while he was still young that made him peculiar from most other northerners, and was the key, I think, in explaining how it was possible for a white antebellum northerner to consider developing a plan such as the one Brown developed to raid Harper's Ferry. This characteristic was his devotion to always follow through with his plans.

In a letter describing his childhood, written in 1858, Brown explained why following through with the plans he made was so important to him. He stated that, as a child, he realized that by enforcing his plans, he could "secure admission to the company of the more intelligent; & better portion of every community." This, being important to Brown, motivated him to always follow through with his plans. In the last paragraph of this letter, speaking in the third person, he also stated:

I wish you to have some definite plan. Many seem to have none; & others never stick to any that they do form. This was not the case with John. He followed up with tenacity whatever he set about so long as it answered his general purpose: & hence he rarely failed in some good degree to effect the things he undertook.

In this statement, Brown revealed that his devotion to follow through with his plans was not something he possessed temporarily during his childhood, after he decided it was important to stick to the plans he made. Rather, it was a characteristic that remained with him throughout his entire life. In reviewing the many plans Brown formed throughout his life, it becomes obvious that this certainly was the case; for only in situations in which certain factors out of his control prevented it, he was always able to enforce the plans he developed.

Some examples of plans he developed and followed through with during his life included his plan to quit drinking. At the age of twenty-nine, Brown began to realize that liquor was gaining control over his life. Therefore, he decided to give up drinking, and from that year on, he never again touched alcohol. Another plan he developed and followed through with was his plan to open his own office to grade wool. This was a plan he developed while involved in the wool business during the 1840's. After becoming convinced that wool buyers had formed a conspiracy to keep wool prices deliberately low, Brown stuck to a plan he had developed to open a new office in which he would be in charge of grading the wool, thereby ensuring fair prices for wool distributors. One other plan I will mention that he developed and followed through with was his plan to quit the wool business and move to North Elba, New York. This plan he developed after taking interest in a section of land in North Elba upon which freed and fugitive slaves were given the opportunity to become farmers. Brown stuck to the decision he had made to relocate his family there, despite the problems he was having at that time selling off his wool at his business in Springfield.

The provisions of his plan to invade Harper's Ferry were even followed through with by Brown with accuracy. For example, the part his plan that specified that no lives were to be taken except in cases of self-defense was never modified; not even during the raid when he was in a position to benefit by threatening the lives of his hostages. As early as 1847, about the time when his plan to invade a region in the south was beginning to evolve, he made this provision of his plan clear in a conversation he had with Frederick Douglass. Eleven years later, according to the testimony of Richard Realf, who was acquainted with Brown during the last three years of Brown's life, Brown specified in a speech in Canada that no slaveholders were to be killed except in cases of self-defense. Two years after that, according to one of Brown's followers, John Cook, on the day before Brown and his recruits invaded Harper's Ferry, he commanded his recruits not to "take the life of anyone if' it could possibly be avoided. But if it was "necessary to take a life in order to save" their own, "then make sure work of it." Finally, after Brown was captured, a Baltimore report claimed that Brown stated he could have killed whom he chose, "but had no desire to kill any person, and would not have killed a man had they not tried to kill him first."

This evidence is further proof that Brown was not exaggerating when he stated in his letter describing his childhood that he always stuck to his plans, for it indicates that he not only maintained this provision of his Harper's Ferry plan from 1847, when he first revealed it to Douglass, until 1859, when the invasion took place, but also maintained it when he was in position to take the lives of his hostages in Harper's Ferry. Had he at least considered taking the lives of his hostages, he may have stood a better chance of negotiating a deal with his enemies. He also could have retaliated for his two sons, (Watson and Oliver Brown), who were unjustly shot and killed at Harper's Ferry after approaching their enemies with a white flag in hopes of a truce. Yet, because he was devoted to maintain his plans, he did not even consider threatening the lives of his hostages.

Unfortunately for Brown; however, his ability to always stick to his plans did not always work to his advantage. There were some cases when he followed through with a plan, even when it was obvious the plan would fail. Perhaps the best example occurred in 1848, when he was preparing to sell the last of his wool in the business he had been running for several years, and move to North Elba, New York. Although he had been offered fair prices by some of his American customers, he was determined to follow through with a plan he had formed earlier to sell his wool over seas in Europe. When one of his associates, Aaron Erickson, learned that Brown was intending on selling his wool over seas, he was appalled. He wondered how Brown could not have known that wool was selling for much cheaper prices in Europe than in America. Despite attempts by Erickson and others to dissuade Brown from going to Europe, Brown followed through with his plan, and in doing so, suffered a severe financial blow.

It is important to note, however, that unlike what some scholars, like John Garraty, have claimed, Brown certainly was not a failure in everything he attempted. Garraty, and others, have argued that the failure of the Harper's Ferry plan was no big surprise, since Brown failed in nearly every plan he developed. To support this argument, they have normally emphasized Brown's fifteen business failures in four different states. What they fail to mention, however, is that while Brown was suffering from numerous business failures, millions of other Americans were suffering from business failures as well due to the panic of 1837. The panic, which lasted from 1837 until 1843, caused manufacturing and farming to "slide into a depression" forcing large numbers "of even the most cautious and calculating investors into bankruptcy." Brown was just one of many Americans trying to succeed in business who became a victim of its effects.

Prior to the panic, however, Brown seemed to find a great deal of success in business. From the time he moved away from his father's home in 1820, all the way through the 1830's, while he was working in the tannery and surveying businesses, he found nothing but success in his life. When he lived in Hudson, for example, during the late 1820's and throughout most of the 1830's, he accumulated numerous employees working under him, bought a large home, was able to open the town's first school, and participated in a variety of other projects to build up his community. It wasn't until the late 1830's, when the panic was at its peek, that he began to become faced with the possibility of failing in his business attempts.

Moreover, Brown succeeded in many other tasks he attempted, not involving business, after the panic was over. For example, he was successful in leading a group of free-soilers to victory against a pro-slavery force in the Battle of Black Jack, which occurred during the summer of 1856 in Kansas. He was also successful a couple of years later in convincing the members of the secret six that he was worthy of receiving financial support. As one of the former secret six members, Samuel G. Howe stated, following Brown's trial, money and living accommodations were provided to Brown after his involvement in Kansas because of his personal worth. This was quite an accomplishment for Brown considering he was not even acquainted with Howe until after he left Kansas in 1857.

Evidence about Brown's life such as this suggests that it would be inaccurate to say he was a total failure. Although, his devotion to always follow through with his plans occasionally got him into trouble, such as in the wool selling case, his failures were not so excessive as to consider him a complete failure in life, for he enjoyed a great deal of success during his life as well.

Since Brown was a man devoted to enforcing his plans, even when they stood a good chance of failing, it becomes more clear how it was possible for a white northerner to consider invading the south, for all Brown would have needed was a plan, and it would have been nearly certain that he would have followed though with it. So the next question would be when and why did he begin to contemplate a plan to free the slaves. Was it during the mid-1850's when he was involved in Kansas? Was it during the 1840's when he was failing in the wool business? I hold that it was much earlier. After reviewing evidence regarding Brown's life, I am convinced he began contemplating a plan to free the slaves in 1812, when he was only twelve years old.

At twelve, Brown made an oath to fight an eternal war with slavery; therefore, being a man devoted to following through with his plans, it was an oath he was determined to maintain. Brown made this oath during the War of 1812 during which he stayed for a short period of time with a U.S. Marshal who happened to own a slave. He stated in his letter describing his childhood that, although he himself was treated well, the slave, whom he regarded at the time as his equal, was "badly clothed, poorly fed; & lodged in cold weather; & beaten before his eyes with Iron Shovels." Upon witnessing how oppressed the young Negro boy was, Brown stated he became a "most determined abolitionist" and swore "eternal war with slavery."

After he made his oath, being a man devoted to enforcing his plans, he often did what he could to help free the slaves from their oppression. Although it wasn't until the mid-1840's when he decided that only by invading the south could he free all the enslaved blacks, he still made frequent attempts to free small numbers of slaves throughout the years following the oath he made in 1812; all while hoping that he would someday develop a reasonable plan to abolish slavery entirely.

One way he helped free slaves was by assisting them to freedom. Brown began assisting slaves to refuges such as Canada quite early in his life. During his early twenties, while working in a tanner in Hudson, Ohio, he assisted at least one slave to Canada, and "made it clear, to anybody who was interested, that he would shelter any other runaways from Kentucky or Virginia who came knocking at his door." Brown was so determined to help assist fugitive slaves to freedom, he added a secret addition to the large barn he had built when he moved to Randolph, Pa. in 1825 for hiding runaway slaves. Later in his life, he even began working with Charles Griffing and Marius Robinson, two nineteenth century abolitionists prominent for their work in the underground-railroad, helping to free five or six Negroes every night through the extensive Ohio Underground Railroad.

Being a pious abolitionist, devoted to ending slavery throughout most of his life; even if it meant dying, and ambitious to follow through with every plan he developed, regardless to how reasonable they were, Brown was well on his way to becoming the first white northerner to attempt to end slavery by invading a region in the south, for no other purpose other than to see an institution he considered immoral crumble. However, there's still the question of why he chose violent means for ending slavery, as opposed to peaceful means, which were by far the most popular during his time. There's also the question of why his plan only called for a small number of men, rather than a large force, which would have stood a much better chance of defeating the opposing forces he was faced with at Harper's Ferry. An attempt to answer these questions will be made in the following chapter.

Chapter Two: On His Own in the War Against Slavery

After he became devoted to liberating the slaves up until about the late 1830's, Brown was, for the most part, open-minded to some of the popular ideas for abolishing slavery that existed in the north, (all of which involving peaceful means to end slavery). For example, he supported William Lloyd Garrison's idea to overthrow slavery "by setting public sentiment against" it "through means of press and pulpit," after he first reviewed the Liberator in 1833. He also, at first, supported some of the ideas of the American Colonization Society, which wanted to take freed slaves, give them schooling, and send them to Africa. He expressed his support for its ideas when, in 1834, he told his son, Frederick that he was considering starting a school for freed blacks; hoping to educate them so that they could become prepared to fight the war against slavery.

By the late 1830's, however, he began to deviate away from the more popular ideas, deciding that only through violence could slavery be abolished; a very unpopular idea in the north during his time. What accounts for this change of beliefs he went through? Although, very little evidence exists describing in detail why his ideas about ending slavery changed, evidence does exist suggesting that he developed a change in consciousness during the 1830's, which ultimately led him to become a strict non-conformist in his attempts to abolish slavery. Becoming a non-conformist could explain why he decided that slavery could only be abolished using violent means, for as a nonconformist, he was no longer interested in the more popular methods that existed in the north.

The two most fundamental factors, I think, which accounted for this change in consciousness by Brown that led him to become a non-conformist were his increased lack of trust in the government, which occurred during the late 1820's, and the opinion he developed that most other white northerners were prejudiced against blacks and cowards when it came to fighting for abolition.

His increased lack of trust in the government was one of the reasons he became a strict non-conformist in his quest to end slavery. There were undoubtedly many reasons why Brown developed a distrust in the government, but the two reasons I think contributed the most to it were the elections of Masons to the government during the late 1820's, and the belief he developed that the government supported slavery.

His belief that the government supported slavery began to develop when he was a young adult, after witnessing slaveholders, such as Andrew Jackson, get elected as Presidents. Although, from his young adult years when this belief he held about the government developed, to the day of his death, the government, on average, consisted of just a few more southerners than northerners, he was convinced the entire government favored slavery and the oppression of blacks throughout these years. He made this sentiment quite clear in occasional letters and conversations. For example, in a letter he wrote to Frederick Douglas in 1854, he stated, in regards to the slavery issue, that the legislatures had always voted for the "most abominably wicked and unjust laws."

In reviewing the decisions made by the government prior to Brown's death, there is little wonder why he clung to such a belief. Especially the decisions made during the last ten years of his life; such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and the Dred Scott decision of 1857; all decisions that favored slavery.

The election of Masons to the legislative and executive branches was another important reason why he began to distrust the government. Brown opposed the Masonic Lodge with extreme hostility. He considered it a secret order that sanctioned murder and harbored slaveholders. Thus, when Masons, such as Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson were elected to the government during the late 1820's, he was outraged. Everywhere he went he denounced the lodge "in the hottest kind of language." Finally, in 1830, after he was almost lynched by a Pro-Mason crowd, he began keeping his opinion about the Masonic Lodge more to himself. Nevertheless, the damage had already been done: his distrust in the government increased.

Brown expressed his distrust in the government frequently following the late 1820's when it increased. For example, he stated in 1856 that a politician was someone you could not trust, for "even if he had convictions, he was always ready to sacrifice his principles for his advantage." He also stated, during his speech in Canada in 1857, that all the laws enforced by America's government "are false, to the words spirit, and intention, of the constitution of the United States, and the Declaration of Independence." Statements like these reveal just how intense his distrust in the government had become just prior to his invasion at Harper's Ferry.

It is also important; however, to note that it was not just the Democrats he was referring to in these statements. Brown made it quite clear in several different letters and conversations that he had no trust in the politicians from the Free State party, as well as those from other parties, such as the Whigs. His distrust in the government was so excessive, he never voted in an election after the year of 1830.

The distrust Brown developed in the government contributed to the change in consciousness he developed during the 1830's, leading him to become a strict non-conformist for a couple of reasons. First, the peaceful approach to ending slavery, which was by far the most popular at that time, most commonly involved appealing to the government. And second, he obviously felt that without the support from the government officials that represented the north, it would be difficult to gain support for his ideas to end slavery from the people of the north in general.

It is important; however, to note that Brown was not dissatisfied with the United States Constitution. Rather, believing that our forefathers who drafted it were opposed to slavery, he gave it one hundred percent of his support. It was only because he felt the politicians of his time were not behaving in the manner our fore-fathers would have intended them to by supporting slavery that he placed no trust in the government. He made this quite clear in article 46 of the provisional constitution he drafted a couple of years preceding his raid, where it was specified that in freeing the slaves, he only wanted to amend the forefather's constitution. He was not seeking a revolution.

The other main reason Brown became a non-conformist in his attempts to end slavery involved the belief he developed that most other white northerners were prejudiced against blacks and cowards when it came to fighting for the abolition of slavery. Various incidents he experienced throughout his life contributed to his development of this belief, which eventually became so strong that he stereotyped nearly every white northerner as a prejudiced coward. One such incident that perhaps contributed the most to the development of his belief that most northern whites were prejudiced occurred at a revival meeting he attended in Cleveland in 1838. As described by John Brown, Jr. "a number of freed colored persons and some fugitive slaves" were present at the meeting, but were given seats by themselves, in a poor place for seeing the ministers or singers. Brown noticed this, and "called attention to the fact that, in seating the colored portion of the audience, a discrimination had been made. He then invited the colored people to occupy his slip."

Rather than being impressed and influenced by Brown's deed, as a truly devoted abolitionist undoubtedly would have, the audience and church deacons responded in a negative way. As John Brown, Jr., stated, they were struck, "like a bomb shell" that Brown had pointed out something wrong in the practices of the church. "The following day the deacons called on Brown to" criticize "him for what he had done. But Brown defied them all." Brown was later cut off from the church for the bold move he had performed, which disgusted him so much, he never became a member of another church after that date.

Upon witnessing how prejudiced people who considered themselves opposed to slavery could be, Brown not only decided to go his own way as a Christian, but also became more convinced that it was pointless for him to cooperate with other northerners in his quest to end slavery. He had always, to an extent, been quite independent in the actions he engaged in to help abolish slavery. However, after this event in Cleveland, "he never joined an antislavery society or other organized abolitionist group" again. He did, of course, continue helping to free slaves by engaging in actions such as assisting enslaved blacks to freedom. However, from 1839 until the time of his death, he engaged in these actions either by himself, or with the help of a small group of individuals in whom he perceived similar attitudes towards slavery as himself Between his distrust in the government, and his perception of other northerners, he evidently felt it would be a waste of his time to participate in the more popular methods that were being used in attempt to abolish slavery at that time.

The last reason why Brown became a non-conformist in his attempts to end slavery was the belief he developed that most white northerners were cowards when it came to fighting for the abolition of slavery. He made this belief quite clear in a conversation between him and Dr. Martin R. Delany, who had interacted with Brown on several occasions during the 1850's, when, in revealing certain segments of his plan to raid Harper's Ferry, he stated that slavery had made cowards of all the northern states. He also stated, in regards to the fight to end slavery, that no effect could be obtained from such people. In this statement, Brown revealed his belief that a coward cannot make a difference; thus, since the majority of the north, through his eyes, were cowards, non-conformity was the only route he could take if he wanted to make any progress in freeing the slaves.

Brown, in fact, became so obsessed with being independent in his quest to end slavery that during the last few years of his life, he was even reluctant to inform some of his most trustworthy allies, (the members of the secret six), of his plan to invade a region in the south. Instead, he made it clear to them that any aid they provided him with was for the defense of Kansas. Most of the secret six members were unaware of Brown's plan, even on the day Brown invaded Harper's Ferry. They were aware that Brown was planning to enforce some sort of plot in attempt to abolish slavery entirely, but they were completely unaware of what his plan involved. I think, not informing the secret six members of his plan to invade Harper's Ferry clearly reflected his attitude as a non-conformist.

The last point I'll make on this issue is that Brown's desire to be independent in his attempts to end slavery was the reason, I think, he was reluctant to admit he had to borrow money and supplies to finance his plan to invade Harper's Ferry. In an interview that took place after the raid, when asked by a reporter where he received the rifles and pikes, Brown replied, "My own money. I did not receive aid from any man." Yet other sources seem to reveal that Brown received at least some of the weapons used at the raid from sources other than himself, such as the Massachusetts Kansas Aid Committee, (MKAC), a committee that had formed for the purpose of aiding abolitionists in Kansas. Samual G. Howe, a former member of the MKAC, for one, implied in the testimony he gave during a trial subsequent to Brown's execution that two-hundred rifles used by Brown's party at the raid were supplied by the Massachusetts Kansas Aid Committee. E. Copie, who accompanied Brown during the raid, also stated that the rifles used at the raid "were furnished by the Massachusetts Aid Society."

The testimony from both these men seem to indicate that Brown was lying when he told the reporter that he had received no aid to finance the weapons used at the raid. However, it could certainly be argued that Brown lied to the reporter about receiving the weapons to avoid revealing the identities of the parties that had supported his raid, such as the MKAC. However, I don't believe this was the case; at least not to a great extent. Keeping the identities of the parties that supported him anonymous may have been part of the reason he lied about the weapons, but considering how much he desired to remain independent in his quest to end slavery, I'm convinced he lied mostly because he was unwilling to admit he was dependent on others for aid. I simply could not imagine Brown confessing to such dependence.

The ties he made with the secret six members were, however, a necessary step in following through with his plan. As a nonconformist, Brown hoped to fund his plan on his own, but after all attempts to earn the money he needed failed, he knew he would be faced with appealing to others for aid, something he was not particularly looking forward to doing. Yet, being dedicated to following through with his plans, he swallowed his pride and did it. This was one of the reasons he got involved in the crisis in Kansas. As will be explained in chapter four, he got involved in Kansas so he could build a reputation as a devoted abolitionist so that people he knew were well financed and would be willing to fund his plan would come to his aid. But, as stated above, as an independent abolitionist, begging for money, as he considered it, was not something he was very fond of doing. For example, just prior to Harper's Ferry, in a couple of letters to his abolitionist allies, Brown expressed defiance for having to reduce to making requests for money. In one letter to Theodore Parker in 1858, in which Brown was requesting $500, he stated, he hoped it would be "the last time" he would "be driven to harass a friend in such a way." Also, in a letter written about the same time and for the same reason to Thomas Higginson, Brown stated he hoped it would be his "last effort in the begging line."

Becoming a non-conformist in his attempts to end slavery could easily have been part of the reason he decided to use violence, rather than peace, in his pursuits for abolition, for by turning against the majority of the north, along with their ideas to end slavery, using violence was basically the only other option he had left. His belief that violence was the best means to end slavery, following his change of consciousness, was made quite clear in a conversation he had with Frederick Douglass in 1847, in which he stated that only through violence could slavery be abolished. This statement suggests that by 1847, he had become truly convinced that violence was the only way to abolish slavery.

Becoming a non-conformist in his quest to end slavery could also be a possible explanation for why his plan to invade Harper's Ferry only called for a small group of men, rather than a large force, which would have stood a better chance of winning a victory in the south. Since he was reluctant to cooperate with the vast majority of white northerners, he was certainly not prepared to let them join him in what he hoped to be the greatest victory of his life. Moreover, because he felt the majority of northerners were cowards, he undoubtedly believed they would not have been of any assistance to him had he invited them to follow him in his ultimate plan to end slavery. It's my opinion that the small number of men his plan called for clearly reflects how much of a non-conformist he had become in his attempts to end slavery at the time his plan evolved. The issue of why he believed he could win a victory against slavery with such a small group of men will be given more attention in chapter four.

Chapter Three: Was He a Thief?

It's been argued by some historians that Brown was a criminal throughout most of his life, and his raid at Harper's Ferry reflected his criminal instincts; for his incentive there, they claimed, was nothing more than the fortunes he felt he could earn. Hill Peebles Wilson was one of these historians. He argued in, John Brown, Soldier of Fortune: A Critique, that the raid Brown led at Harper's Ferry was desperate attempt by Brown to restore the fortunes he had lost in his business failures earlier in his life. He supported this argument by providing evidence suggesting that "the years of Brown's life were a constant, persistent, strenuous struggle to get money," and that Brown cared nothing about the "means that should be employed in the getting of it." This evidence consisted mostly of accounts of robberies Brown engaged in, such as the steeling of horses belonging to pro-slavery men in Kansas.

James Malin, who also argued in, John Brown and the Legend of Fifty-six, that Brown's invasion at Harper's Ferry was an attempt to get rich, was even more critical towards Brown than Wilson, saying Brown was not a great villain as Wilson portrayed him, but an insignificant frontier crook and petty horse thief Furthermore, he argued that Brown had no interest at all in the free-soil cause in Kansas, and that it was a myth that he was interested in liberating the slaves. According to him, the Harper's Ferry invasion was not the only attempt by Brown to make money. He claimed that Brown also had his appetite for fortunes on his mind in every other plan he enforced during his adult years. Like Wilson, Malin also emphasized the horse robberies he claimed Brown participated in while in Kansas as evidence supporting him argument.

Although these arguments made by Malin and Wilson appear rather convincing and were supported by a great deal of evidence, other evidence they seem to have ignored suggesting Brown was not a criminal, contradicts what they said about him.

For example, the evidence provided in the first chapter indicating how religious Brown was throughout his life suggests he would not have been the type of man to engage in the criminal activities he was accused of engaging in by Malin and Wilson. Being the devoted Christian he was, robbery would have been strictly against his religion.

Also, although evidence does reveal that Brown occasionally participated in looting stores and steeling horses while he was in Kansas during the mid-1850's, other evidence not mentioned by Malin and Wilson suggests Brown did not keep any of the profits he had made from these robberies. For example, according to testimony from witnesses, in 1856, Brown and some of his followers participated in looting a shop owned by Joab Bernard in the city of Black Jack, Kansas, helping themselves to between $3,000 and $4,000 worth of supplies and a few horses and cows, after winning a battle fought earlier in Black Jack against pro-slavery forces. This particular incident was used as support for the theses of both Wilson and Malin's monographs. However, what was not mentioned by Wilson or Malin was that Brown kept none of the plunder taken from Bernard's shop for his own personal gain. Rather, he used the money and stolen supplies for the continuation of the struggle in Kansas. This fact refutes the claims made by Wilson and Malin, for if Brown truly had been a criminal, he certainly would have kept at least a portion of the loot from Bernard's shop for his own personal gain.

To me, authors who have claimed that fame and fortune were the motives that drove Brown to invade Harper's Ferry were biased in their research for the simple fact that they found it too difficult to believe that a Euro-American would go through all the trouble of planning and enforcing an invasion in the south only to satisfy his desire to end slavery. I do not; however, share this outlook. As the facts from the first chapter of this work suggest, given the right characteristics and environmental background, it certainly was possible for an antebellum white northerner to be so determined to end slavery, that he'd devote a vast portion of his life to developing a plan to abolish it entirely. Brown was that man. He was not a thief, or a madman, (as the next chapter will explain); rather, he was just a white northerner with a burning desire to see slavery become abolished. This was the only reason he invaded Harper's Ferry.

Chapter Four: Was it a Crazy Plan Thought up by a Madman?

One other big issue involving the raid Brown led at Harper's Ferry that has probably caused the most controversy amongst historians and scholars of the past is whether or not Brown was insane when he invaded Harper's Ferry. To most of the earliest historians who published literature about John Brown, such as James Schoular and Allen Nevins, there was little doubt Brown lacked sanity, at least in issues involving slavery, at the time he invaded Harper's Ferry. Even in some of the most recent literature about John Brown the insanity explanation for the Harper's Ferry raid has been used. For example, in an article from 1996 by J.C. Fumas, it was argued that the members of the secret six who helped fund Brown's plan should have perceived Brown as a mental case rather than provide him with money and supplies to enforce a plan that they knew little about. In another recent article by Geoffrey C. Ward, Brown was considered a madman for enforcing a raid that was considered by Ward as crazy and irrational.

In reviewing the facts regarding John Brown's raid, it becomes quite clear, for a couple of reasons, why so many scholars and historians have concluded that Brown was insane, at least in issues involving slavery, at the time he led the Harper's Ferry raid. First, in literature containing the statistics that were involved with the raid, it seems apparent that Brown and his followers had no chance of succeeding. Saying Brown was insane; therefore, was the easiest way for them to explain an assault by eighteen men against a federal arsenal and the state of Virginia. And second, there is plenty of evidence from Brown's trial supporting their argument that Brown was insane at the time of his raid, including testimony and depositions from certain people who knew him and affidavits submitted to the trial by Brown's attorney. One example of a deposition from Brown's trial that provided support to the argument that Brown was insane at the time of the raid came from E.N. Sill, who had known both Brown and Brown's father. Sill stated that he thought it was unsafe for Brown to be "commissioned with such a matter" as he was in Kansas, and that he had no confidence in Brown's judgment in matters appertaining to slavery. It was from this testimony by Sill that Allen Nevins based his argument that "on all subjects but one slavery and the possibility of ending it by sudden stroke which would provoke a broadening wave of uprisings as a rock thrown into a pond sends forth widening ripples" Brown was sane.

Other evidence from Brown's trial used by some historians to support their argument that Brown was insane at the time of the raid included the affidavits submitted to the judge and jury by Brown's attorney, George Hoyt. These affidavits, (nineteen in all), were from "Brown's friends and acquaintances" and all purported to demonstrate Brown's instability. Some of the people they addressed included Brown's maternal grandmother, his sister, his brother Salmon, his first wife Dianthe, his son Frederick, and many of his uncles, aunts, and cousins. In some of them, like his grandmother's, it was confirmed that the individual addressed was mentally ill. Others contained testimony from friends and family who believed Brown, himself, was mentally incompetent.

Some historians, such as James Schoular and Allen Nevins, took this evidence at face value. Others, on the contrary, such as Stephen B. Oates, considered this evidence, and other evidence from Brown's trial supporting the insanity explanation, unreliable. Oates emphasized the fact that much of the affidavits were heresay, and that they were not based on objective clinical evidence gathered by doctors who wanted to establish Brown's sanity. Furthermore, he argued that the insanity explanation appealed to political leaders; for "moderates from both the north and south, seeking to preserve the Union, needed an argument to soften the divisive impact of Harper's Ferry." Oates made clear in his biography his belief that Brown was sane, and that historians who dismiss him as an insane man, "ignore the tremendous sympathy he felt for the suffering of the black man."

I agree with Oates that Brown was not insane at the time he led the invasion at Harper's Ferry for a couple of reasons in addition to the one's asserted in Oates's biography. First, most historians, such as Schoular, who have used insanity to explain Brown's raid believe that Brown's insanity originated sometime between 1856 and 1857, during his involvement in the Kansas crisis. This was a reasonable time to say he became insane for a couple of reasons. First, it was a time when Brown suffered numerous hardships, like the loss of his son, Frederick Brown, and the loss of the city of Lawrence, where many abolitionists like Brown had made their dwellings. And second, it was during Brown's involvement in Kansas when he engaged in the famous Pottawatomie massacre, in which he helped take the lives of five pro-slavery men. In Schoular's narrative it was specified that around the time of these massacres Brown became insane. He stated that Brown's "mind had been strangely unstrung by the murderous scenes in Kansas in which he had borne a part."

Other evidence, however, seems to refute these claims made by Schoular and others by suggesting that Brown had developed a plan very similar to the one he actually enforced in Harper's Ferry, before he even became involved in the crisis in Kansas. For example, Richard Realf, who had been the Secretary of State of Brown's proposed government, (which he created at a convention he held in Chathan, Canada on May 10, 1858), testified in 1860 that Brown had stated to him in December of 1857 that he had been contemplating a plan to liberate all the slaves in the south for twenty or thirty years. He did not say whether or not Brown's plan to free the slaves involved an insurrection throughout all that time, but he did mention that Brown stated, later in a speech at his constitutional convention in Chatham, Canada that "he only went to Kansas in order to gain the footing for the furtherance" of the insurrection of slaves he was planning in the south.

This indicates that, although Brown may not have been planning a full scale insurrection throughout the 20 or 30 years he claimed to have been contemplating a plot to free the slaves, he did begin planning a full-scale insurrection before he became involved in Kansas; thus, according to this evidence, to say it was a change in his mental behavior that developed in Kansas that caused him to begin planning a full scale insurrection would be inaccurate.

In the biography by Frederick Douglass, who had become well acquainted with Brown during the 1840's and 1850's, it was also implied that Brown became involved in Kansas mostly just to gain the support he needed to pursue an even greater plot he had been contemplating. Douglass, referring to a visit he had with Brown in 1847, stated that:

Captain Brown, notwithstanding his rigid economy, was poor, and was unable to arm and equip men for the dangerous life he had mapped out. So work lingered till after the Kansas trouble was over. This left him with arms and men, for the men who had been with him in Kansas, believed in him, and would follow him in any humane but dangerous enterprise he might undertake.

This passage in Douglass's biography suggests that Brown had already decided to pursue a plan to free the slaves that involved the use of arms at the time of his visit with Douglass in 1847, but was unable to pursue it because of his lack of men and finances; thus, he became involved in Kansas to build a reputation as a devoted abolitionist so that men would follow him and people would financially support the more ultimate plot he was planning to free the slaves.

In regards to the plan Brown discussed with Douglass in 1847, Douglass stated that it involved twenty to twenty-five armed men, all of whom would help free slaves, and would use the mountains of Virginia and Maryland as a place where they could easily defend themselves against opposing soldiers or slaveholders. This suggests that the plan Brown revealed to Douglass in 1847 was remarkably similar to the one he actually followed through with twelve years latter. Although it may not have involved a complete slave insurrection at that time, as it would later, it certainly involved a small number of men that Brown knew would be risking the possibility of being faced with a large opposing force.

It was this portion of Brown's plan that undoubtedly convinced many scholars and historians to consider insanity as the only reasonable explanation for the raid Brown led at Harper's Ferry. How else could they explain how Brown would consider invading a region in the south with such a small army? Yet, if Brown was planning to provoke a full scale insurrection in the south with an army of only between 20 and 25 men before he even became involved in Kansas, then it could not have been insanity, which many authors claim evolved during his involvement in the crisis in Kasas, that enabled him to follow through with such a plot.

So the next question would be, it he was not insane, what possibly could have convinced him that he stood a chance of winning a victory in Harper's Ferry with such a small group of men? Part of the reason, I believe, was explained in chapter one: he was determined to follow through with every plan he developed, regardless to how irrational they were. As explained in chapter two, because he had become such a non-conformist in his attempts to end slavery, a small group of men, (which ended up consisting mostly of his sons and freed and fugitive slaves), was all he felt he could rely on in pursuing his ultimate plot to end slavery; thus, determined to follow through with every plan he developed, he went ahead and invaded Harper's Ferry, despite how small his army was.

The other part of the reason is far more elaborate, and somewhat ambiguous; yet, evidence still suggests that it could easily have been a fact. This was that Brown had become familiar enough with the area surrounding Harper's Ferry and the consciousness of the people, both black and white, who lived in the surrounding area to believe he actually stood a chance of defeating the opposing forces he knew he would be faced with when he entered Harper's Ferry.

By using the area surrounding Harper's Ferry, Brown's army easily could have defended themselves against a large opposing force. Bathe Stavis provided a good description of Brown's chances of winning a victory against the south by utilizing this area in his monograph, John Brown: The Sword and the Word. He said that the mountain wilderness of the Alleghenies, (which was only a three hour journey on foot from Harper's Ferry), was filled with caves, deep ravines, and natural fortresses, which would have allowed ten men, using guerrilla warfare, "to hold off a hundred." Had Brown been familiar with this fact; therefore, it certainly would have increased his hopes of winning a victory against the south. But was he aware of this fact? Before this question can be answered, one other point needs to be made.

Stavis also provided a good description of Brown's chances of provoking an uprising: not of slaves, but of the white men who operated small farms in the outskirts of Harper's Ferry. According to him, these farmers, (who were known as hillbillies, crackers, and poor whites), had been oppressed for more than fifty years prior to the Civil War by large plantation owners who manipulated politics in Virginia to favor their own economic interests. Being subject to severe class division, as well as ethnic division, for most of these small farmers were Scotch-Irish, rather than English, like most of the plantation owners, many of these small farmers, argued Stavis, would have been more than willing to engage in battle against their fellow southerners who owned plantations.

One good example of an account, which occurred just a few years following Brown's execution, in which these small southern farmers actually did conspire against their fellow southerners, was towards the end of the Civil War. According to James Henretta in, America's History, conspirators against the confederacy known as Unionists, who "aided northern troops and sometimes even enlisted in the Union army," increased intensely towards the end of the war in regions such as the Appalachian Mountains. Since a vast portion of the Appalachians are located in West Virginia, and since this incident occurred only a few years after Brown's raid, this evidence strongly supports Stavis's argument that the small farmers of Virginia were prepared to conspire against their fellow southerners at the time Brown invaded Harper's Ferry. Had Brown been familiar with this fact, it would have increased his expectations for a victory in the south. However, the question again comes up of whether or not he was familiar with this fact. According to evidence regarding Brown's life, an article from his provisional constitution, and testimony from witnesses to his raid, I'm convinced that he was familiar with the facts regarding the small farmers in Virginia, as well as the area surrounding Harper's Ferry, long before he led his invasion.

In an article by Boyd Stutler called, "John Brown and the Oberlin Lands," an account was mentioned in which Brown interacted with numerous small farmers and investigated vast amounts of land in West Virginia in 1840, nineteen years prior to his raid. According to Stutler, in 1840 Brown was hired by Oberlin College in West Virginia as an agent of their college, and was authorized "to enter upon, explore, and occupy" the College's property. Brown; therefore, traveled to West Virginia and spent April and May of 1840 surveying the College's property "which lay in a fertile region just south of the Ohio River and some eighty miles west of the Allegheny and Appalachian Mountains." While surveying this land, according to Stutler, Brown investigated the culture and farming methods of the people in the area. He then returned to his home in Ohio, and due to new opportunities in the wool business, he resigned from his job as an agent for the College.

Brown easily could have taken advantage of this opportunity to learn if the surrounding land was suitable for fighting opposing forces, and if the people in the area were willing to support an uprising intended to abolish slavery. However, neither Stutler, or Oates, (who also mentioned this account in his biography), believed Brown used this opportunity for this reason. In contrary to Oates and Stutler, I hold, for a couple of reasons, that Brown did use this opportunity to estimate his chances of provoking a massive uprising and defeating any opposing forces he may have been faced with; not particularly to liberate all the slaves at the time he did the surveying, but at least to coerce the emancipation of some of them.

First, since Brown already could have been considering some sort of invasion against the south at the time he did the surveying in Virginia, he could easily have taken advantage of his time spent there to estimate his chances of winning a battle against the south. As the evidence mentioned in chapter two suggests, by the late 1830's he had already decided that only through violence could slavery be abolished; thus, because he was determined to help abolish slavery ever since he was twelve years old, he undoubtedly would have perceived his experience surveying in Virginia as a perfect opportunity to become more knowledgeable with the land and society he had to work with.

Second, evidence exists suggesting Brown did take advantage of the knowledge he gained while in Virginia in 1840 to guide him through his plan to end slavery by invading the south. For example, during his 1847 visit with Frederick Douglass, he explained how easy it would be for him to defend an army against opposing forces using the caves and ravines in the Alleghenies. This suggests that somehow he had become familiar with the Alleghenies, and hoped to utilize his knowledge about them for engaging in battle.

Other evidence also suggests Brown was considering inviting small farmers from Virginia to join him and his followers in a raid against the south. In article I of the provisional constitution he drafted in 1858, he mentioned that anyone from the oppressed races of the south were welcome to join the proposed government he developed in Chatham, Canada. Being a strict non-conformist, unwilling to cooperate with most people who were even opposed to slavery, it seems rather strange that he would allow people from the south to join his proposed government, unless he was already aware that they would join him in an uprising to end slavery.

He also considered the people he referred to in this article as "oppressed races." Since the small farmers of Virginia were certainly oppressed, and mostly came from different races than the plantation owners who had oppressed them, he easily could have been referring to the same small farmers whose land he surveyed in 1840. Therefore, since 1840 was the only known time in which he was in Virginia, other than the short time he stayed there in 1859, prior to his raid, it could easily have been the case that he utilized his experience in Virginia in 1840 to discover whether or not the small farmers there would support him in an uprising. In discovering that they would support him, his confidence that he could defeat any opposing force he was faced with when he did enforce an uprising in the south by gradually increasing the size of his army, would have vastly increased. Undoubtedly, it was only because his raid was suppressed much quicker than he expected that such an uprising never actually did occur.

In regards to the slaves from the surrounding area of Harper's Ferry, it is also possible that he utilized his time in Virginia in 1840 to discover whether or not they would support an uprising to end slavery as well, for, despite the myth that no slaves came to his aid as he had expected they would, evidence suggests that a couple of slaves did come to aid during the short period of time in which he held Harper's Ferry. For example, in an interview with John Allstadt, (a slaveholder who was taken prisoner by Brown's crew on the first day of the raid), it was stated that all the slaves that were taken from Allstadt's farm by Brown's crew were returned to his plantation after the raid was suppressed, except for one. The slave that was not returned, said Allstadt, was taken to a jail in Charlestown, Virginia, and died shortly after from a cause he was unsure of. This testimony from Allstadt suggests that the slave that died in jail had supported Brown's raid. Although it was not specifically stated that this slave came to Brown's aid, it would have been very unlikely that a slave who had expressed opposition to Brown's raid would have been tossed in jail and possibly executed.

In an interview with Lewis Washington, who also was taken prisoner by Brown's crew, a possible account of another slave that supported Brown's raid was revealed. According to Washington, as he was taken prisoner, a slave named Hayward, from a neighboring plantation, owned by a plantation owner named Dr. Fuller, heard the commotion and willingly got into a wagon Brown's crew had been using to hall weapons. Washington further stated that after he was released, following the suppression of Brown's raid, he was informed that Hayward had been drowned. This testimony suggests that Hayward also came to Brown's aid, for, like the slave who perished in jail, the southerners undoubtedly would not have taken the life of a slave who opposed Brown's raid, and it's even more unlikely that Brown's crew was responsible for taking this slave's life.

Since this evidence suggests that it was possible the slaves were beginning to support Brown's raid shortly before Brown and his followers were crushed by opposing forces, it's also possible that Brown became aware of the fact that the slaves around Harper's Ferry were willing to support an uprising to end slavery when he was surveying land in Virginia in 1840. Being aware of this fact, like being aware that the small farmers would support his raid and the land around Harper's Ferry was suitable for defending an army against opposing forces, would have increased his confidence of winning a victory against the slaveholders from the south.

So if it's true Brown was aware that a successful uprising would certainly have been possible by invading Harper's Ferry, then it would be foolish to accuse him of being insane; for in reality, his plan would have been a rather intelligent plot, that failed only because his raid was suppressed much sooner than he had anticipated.

Brown was not insane, nor was his plan a crazy plot. Although, it was a rather desperate attempt to end slavery, according to the evidence from this chapter, it still stood a fair chance of succeeding. Being a sane man, whose greatest desire in life was to see slavery abolished and who felt he had very little support from anyone else for his ideas; however, it was undoubtedly the best attempt he could possibly have made to abolish an institution he considered evil and immoral.

Bibliography

I. Primary Sources:

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Hartford, Connecticut: Park Publishing Co., 1881. (Autobiography).

Fairchild, James Harris. Underground Railroad. Cleveland, 1895. (Eye-witness account).

Fogelson, Robert M. and Robenstien, Richard E. Invasion at Harper's Ferry. New York Arno Press & the New York Times, 1969. (Articles of Provisional Constitution and testimony).

Hinton, Richard J. John Brown and His Men. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1894. (Letters and testimony).

"Pate's Version of the Battle of Blacks Jack." New York Tribune. June 17, 1856.

"Report of Commissioners of Kansas Territory." U.S. House Committee Reports. III. 36th Congress, 2"d session, 1861. (Testimony).

Sanborn, Franklin B. The Life and Letters of John Brown. Boston: Robert Brothers, 1891. (Letters, Testimony, and eye-witness accounts).

Stavis, Barrie. John Brown: The Sword and the Word. Canbury, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1970. (Letters).

"The Insurrection at Harper's Ferry." (October 18, 1859). http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/jbrown/news.vs/vsbrown4.gif (Newspaper article about the raid).

Warch, Richard and Fanton, Jonathon F. John Brown. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1973. (Letters, testimony, documented interviews, portiom of other Autobiographies).

II. Secondary Sources:

Periodicals

Furnas, J.C. "Virucrats on the Loose." The American Scholar. (1996), pp. 310-312.

Park, Edward. "John Brown's Picture." Smithsonian. (1996), p. 19-20.

Stutler, Boyd B. "John Brown and the Oberlin Lands." West Virginia History, XII (April 1951), pp. 189-199.

Sutler, David B. "Abraham Lincoln and John Brown-A Parallel." Civil War Hisory. Vol. VIII (September, 1962), p. 296-299.

Ward, Geoffrey. "Terror, Practical or Impractical?" American Heritage. Vol. 46 (September 1995), pp. 14-15.

Books

Davidson, James West and Lytle, Mark Hamilton. "The Madness of John Brown." After the Fact: The Act of Historical Detection. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc., (1992), pp. 122-148.

Henretta, James, "et. al." America's History to 1877. Worth Publishers, Inc., 1993.

Malin, James. John Brown and the Legend of Fifty-Six. Philadelphia, 1942.

Nevins, Allan. The Emergence of Lincoln. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1950.