- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

History Lessons: Chartism 1832 - 1948

The recent TV series Boardwalk Empire covers a period in time where women fought for the right to vote in the United States. It is is easy to forget that even in most democracies that most men didn't have the right to vote until relatively recently.

This article is the Chartist Movement in 19th century Britain which fought and protested for suffrage for the working classes.

The Great Reform Act 1832

Chartism began after the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832. The act was a mild reworking of the voting system, meaning that most men within the emerging middle class could vote. It also allowed growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds to be better represented in Parliament, and reduced the number of rotten boroughs where constituencies were so small that a wealthy man could easily buy his way into parliament. But many people were unhappy with the act, and concerned that it didn’t go far enough. Only one in ten men could vote and electoral districts were still uneven. Some had less than 300 electors, while Liverpool had over 11000.

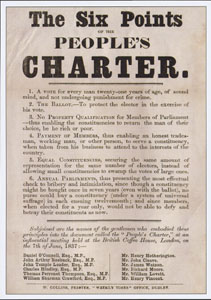

William Lovett, Henry Hetherington and others set up the London Working Men’s Association in 1836. The ideas of the group were a reaction to the Great Reform Act, as these working class men felt marginalised by the short reach of the bill. By 1838 the group had drawn up a manifesto of sorts, which they named The People’s Charter. This had six points relating to parliamentary reform:

- The first was a vote for every man over 21.

- The second was a secret ballot, so that people could vote without fear of reprisals from their landlords.

- Third, an end to property qualifications to become an MP, meaning anyone, rich or poor, could become an MP.

- The Fourth was payment of MPs, as no working class man could afford to become an MP without this measure.

- The fifth point was equal constituencies, in order to avoid misrepresentation.

- Finally, the Charter demanded annual Parliaments, which they believed would make bribery and intimidation by potential MPs almost impossible.

In a leap of spectacular imagination, the members of the London Working Men’s Association became known as the Chartists, and set about organising themselves in order to bring about real electoral reform as they saw it.

Petition and Protest

Their first major move was a petition to Parliament in 1839, based on the Charter. Over 1250000 people had signed the petition. Despite this, Parliament voted against hearing the petitioners’ views. This sparked violence in some areas, some from the more agitation inclined Chartists, and some from the authorities who were worried by Chartism. The worst of the violence was in Newport, where police opened fire on Chartists in a hotel, killing twenty-four and injuring a further forty.

The Chartist movement was initially non violent, and it’s demonstrations civilised. They occasionally caused disruption, but even then used words rather than violence to spread their message. However, Feargus O’Connor set up another Chartist group, the East London Democratic Association, which was more interested in using physical force than Lovett’s moral force approach. When O’Connor took control of the National Charter Association upon his release from prison for libel in 1841, many of the old leaders (including Lovett) left the movement, unwilling to be associated with violence.

By this time the ‘moral force’ Chartists, as typified by Lovett, were reduced to the role of observers, as the ‘physical force’ Chartists became the dominant group within the movement. Many of the original Chartists were imprisoned, leaving O’Connor and his ‘agitators’ to take control. Further petitions were presented to Parliament, but these had little effect. It was the final petition in 1948 which virtually ended Chartism as a credible movement. It contains less that two million signatures, rather than the 5 million claimed, and many of these were duplicates or forgeries, including the bold move of adding ‘Queen Victoria’ and ‘Duke of Wellington’.

Self improvement and literary tradition

The two sides to the Chartists were very important in terms of gaining both popularity and notoriety. Chartism’s moral objectives “strongly impressed conscientious minds among the ruling classes, while the threat of physical force which accompanied it compelled the attention of those who might otherwise have remained blind.” (House, 1941, 48)

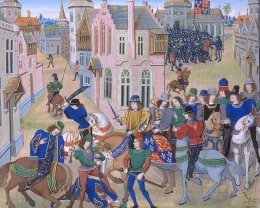

The Chartists certainly had much in common with other political movements of the time, and indeed of the past. In terms of ideals, the Chartists had similar motives to both Wat Tyler and his followers and the 17th century Levellers, demonstrating and campaigning for more power on behalf of the lower classes. The moralism and self-improvement ethic that seem to typify the mid-nineteenth century was clearly present within early Chartism and the other movements of the time.

The Chartists, in keeping with the self-improvement ethic, began to campaign for more access to places they considered to be of cultural importance in an attempt to lure their followers away from the public houses. However, this was slightly awkward, as many Chartist meetings were held in pubs, and Chartists could not afford to denounce those who provided their meeting places. The ‘physical force’ Chartists had few issues with such matters, but some ‘moral force’ Chartists wished for a teetotal movement. Lovett campaigned for the Sunday opening of museums, and stated, “the best remedy for drunkenness is to divert and inform the mind” (Lovett, quoted in Golby, Purdue, 1984: 93).

Chartists also attempted to create a literary tradition of their own, and, as well as spreading their political message, sought to attack and replace “the sort of popular literature which was written for the poor and which invariably consisted of tales about the better-off, where the labouring classes were very often represented as good-natured but comic” (Golby, Purdue, 1984: 93). This was a departure, as no other group had tried to improve the way in which the working classes were portrayed within literature.

Conclusions

As a reaction to the 1832 Reform Act, Chartism can be seen to break new political ground. Previous radical groups consisted of the working and middle classes “allied in their fight against the ‘old corruption’ of the landed aristocracy” (Huggett, 1978: 9). With the reform act giving suffrage to the middle-classes, the workers were left with only a few middle-class supporters, and so “had to continue their fight against the establishment by other means, the Chartist movement.” (Huggett, 1978: 9)

Chartism had much in common with other political groups, both in their essential ideals and their more esoteric intellectual pursuits. They shared a sense of morality and an urge to promote self-improvement with most groups, and despite a large female following made no attempt to seek votes for women. But there are two new political departures within the Chartist framework: With the middle-classes now able to vote, the working class had to work with little support from them for the first time, and they were one of the first groups to have the foresight to attempt to improve the way the working-classes were represented in print.

Sources

- Golby, J.M., Purdue, A.W. (1984) The Civilisation of the Crowd: Popular Culture in England 1750-1900, Stroud, Sutton. p. 86, 87, 93

- House, H. (1941) The Dickens World, London, Oxford University Press. p. 48, 106

- Huggett, F.E. (1978) Victorian England as seen by Punch, London, Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 9, 39, 40