- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Military History

History of The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle

As the first true American made firearm, the Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle has helped define the United States of America.

This flintlock rifle used European type weapons as a base and then people began to innovate and craft them to suite their needs. The person, culture, and area the weapon was used all changed, but never at the cost of its artistic craftsmanship.

The Creation of The Longrifle

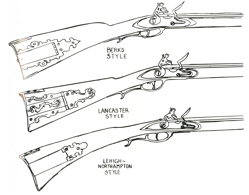

The Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle was originally built in Pennsylvania. The primarily German inhabitants settling along the Susquehanna River, Delaware River, and everywhere in-between, brought with them their traditions as they migrated up these rivers and away from Philadelphia. Well, as it turns out, one of their greatest and most prized traditions happened to be crafting firearms.

The "Pennsylvania-Dutch", as they are now commonly referred to today, brought with them the German made Jäeger. This rifle was the basis, along with the stock architecture of a Brown Bess, for the American made Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle (Heckert and Vaughn). However, many non-Quaker English and Scotch-Irish settled the same area and helped develop this firearm.

The English and Scotch-Irish contributed to the development of this rifle by pushing further and further into the previously unknown area. These frontiersmen needed reliable and accurate firearms as they moved North and East away from city life in Philadelphia.

These diverse cultural groups converged at places such as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Gunsmiths, riflemen, and artisans exchanged ideas, shed knowledge, and learned new skills which evolved into this unique style of rifle (Heckert and Vaughn).

Containing as many as 44 to 52 pieces (depending on the lock, trigger, etc.) made the crafting of these firearms slow and dependent on an abundance of raw materials (Heckert and Vaughn).

Pennsylvania-Dutch

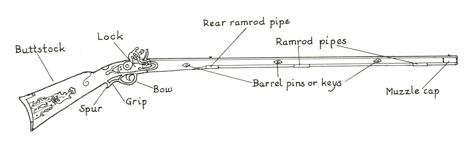

The Parts

The regions abundance of iron ore, limestone, lead, and ample hardwood for stocks provided everything the frontiersmen needed to create the Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle.

These rifles did go through three distinct phases: 1720-1770 (transition period), 1770-1835 and 1835-1860 (Heckert and Vaughn). Many of the rifles from the transition period had thick buttstocks and a general contour comparable to the German made Jäeger (Heckert and Vaughn). Also of importance to the frontiersmen was Native American trade. During the transitional period (prior to 1755) many of the Lancaster made rifles were supplied to local tribes (Heckert and Vaughn).

Barrel

The Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle could have been fitted with two different barrels: rifled and smoothbore.

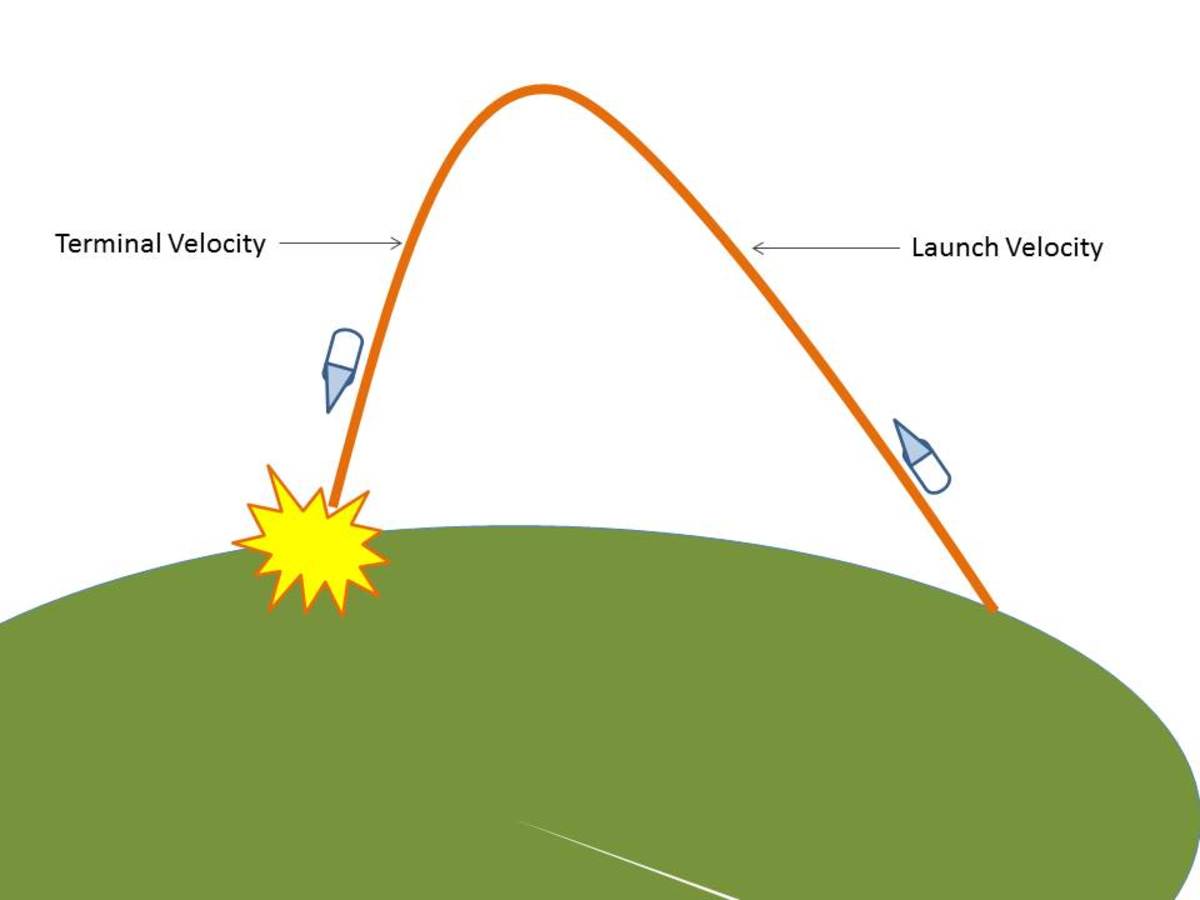

The rifled variation to the firearm would have had an octagonal barrel (Grinslade) with grooves on the inside. Early rifling gunsmiths perfected a method of rifling that reduced the average bore size which resulted in improved economy, increased velocity, longer maximum range, and convenience in a sense that more ammunition could be carried for the same weight (Heckert and Vaughn).

Rifled barrels were made with a number of style of grooves. The most common configuration was seven square grooves with a depth of approximately .010" cut from breech to muzzle (Heckert and Vaughn). Rifling grooves were cut out by steel toothed rifling bits inlaid into an iron rod that was pinned to the spiral guide of a rifling machine (Heckert and Vaughn).

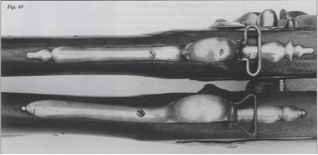

The fowler (smooth bore variation) would have had a thinner barrel wall, octagonal-to-round shaped barrel, and no rifling (Grinslade).

There was no prescribed length of barrel and discretion was left to the craftsmen if a length was not already specified by the person placing the order. Typically, the barrels would be longer than that of most European made weapons.

Lock

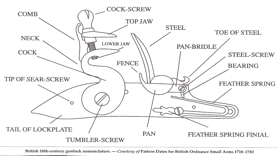

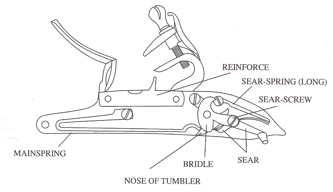

The most complex part of the firearm, the lock, consists of approximately 26 working pieces. Stamps left on this portion of the weapon identify its origins which can be traced back to the locksmith.

Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle locks were made completely from scratch, if they had not been purchased through trade from England (Heckert and Vaughn). Forged from iron with nothing more than a hammer and anvil the first parts crafted were the lock-plate and cock, with all other parts made to fit these two (Heckert and Vaughn).

The process of lock making was very complex and time consuming and not many frontiersmen were capable of the task. This forced many of them to purchase locks in Lancaster brought over from Birmingham, England (Heckert and Vaughn). In Kaufman's book, The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle, he provides a list of names of lock makers, locations, and years(s) they produced them.

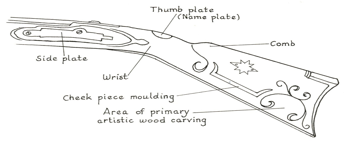

Butt/Butt Plate

The overall butt end of the weapon allowed craftsmen to add on their artistic signature. Various attributes, height and width of the butt/butt plate and length of butt tang, show a degree of personalization (or lack thereof) from weapon-to-weapon and allow for someone to identify the type of person carrying and crafting the firearm.

Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifles typically had a butt that was flat on its underside (trigger side) that extended from the toe, the back (if the barrel is viewed as the front), to the trigger guard (Grinslade). The butt typically had a cheek piece, a patch box, and a butt plate, with the tang squared off and faceted to the stock.

Like other portions of the weapon, the fowler and rifled variations had different butts/butt plates. the cheek piece on the rifle often had a silver "Star of Bethlehem" or a so-called "Hunter's Star" for luck (Heckert and Vaughn). The fowler typically had no patch box, no cheek piece, and the tang of the butt plate extended into a rounded tip (Grinslade).

The patch box was used to hold pieces of leather or cloth in tandem with ammunition (see ammunition below). These American made rifles had a hinged brass patch box with the brass providing yet another medium for creative expression from the craftsmen (Heckert and Vaughn). Since these weapons were custom made, the patch boxes were made to the needs of the individual. The opening mechanism could be located on the top of the butt, on the toe plate, at the bottom of the stock when held in a firing position, or on the side near the lid (Heckert and Vaughn).

Trigger/Trigger Guard

While serving as the part of the gun that starts the process of shooting a projectile out of the barrel, the trigger/trigger guard was also a place for the person crafting the weapon to use some artistic flair and add a "signature" to their work.

As with the barrel, the trigger guards for the fowler and rifle were different. Similar to the Brown Bess Pattern 1730, the Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle fowler variation had a rounded bow shape trigger guard (Grinslade). The rifled variation also had a rounded bow trigger guard, but with a grip rail (Grinslade). From what I can imagine, the rifled variations grip bar helped with accuracy. Both trigger guards were made of brass (Heckert and Vaughn).

As far as I know in regard to the triggers, they were both the same. The triggers started out in the standard British or European style. However, in the later part of the transitional period the double-set ("hair") trigger was developed (Heckert and Vaughn). The "hair" trigger increased accuracy, which would have been more optimal for the rifled Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle. Minimal pressure was needed to squeeze the double-set trigger meaning less muscle movement was required allowing for more accuracy (Heckert and Vaughn).

Ammunition

The primary type of ammunition used in the Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle was patch and ball. However, in the smooth bore variation of the weapon this would have been pointless as accuracy was not the primary objective. Thus, a standard musket ball, buck shot, or combination of the two would have been utilized.

Patch and ball is rather self explanatory. A ball was literally wrapped in a piece of greased cloth or thin piece of leather and pushed down the barrel. The ball being wrapped in cloth or leather prevented gas from escaping the barrel from the smaller caliber ball used in the rifles. Also, this prevented the ball from bouncing around the barrel. This dramatically increased the accuracy of the rifles. They were accurate up to 200 yards (Heckert and Vaughn).

As with many of the other parts of the weapon, the ammunition was custom made to fit the needs of the frontiersmen. Gunsmiths often had to create custom molds to create a caliber ball to fit properly into the barrel of the rifle. The more popular calibers were .4" to .6" (Heckert and Vaughn).

Conclusion

From the time these weapons started being produced to today, they exemplify the vast cultural stirring pot that helped make and define the United States of America.

People from all around the world helped in creating and improving this weapon. The original, the German made Jäeger, was expanded to fit the needs of the frontiersmen using the weapon. The different barrels and artistic embellishment reflected the individual behind the firearm and defined not only how it was used, but beliefs of the person using it.

Its extraordinary accuracy proved vital in the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War. This weapon set the ton for all other weapons in the department of accuracy and it helped the British and then the United States of America win wars. Without this weapon, history could have been different from what it is today. Good or bad, that is for you to decide.

This weapon is a prized possession of any gun collector and a true piece of American history.

© hockey8mn, 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Sources

Ahearn, B. 2005. Flintlock Muskets in the American Revolution and other Colonial Wars. Andrew Mowbray Publishers, Lincoln, RI.

Bailey, D. 2009. Small Arms of the British Forces in America: 1664-1815. Mowbray Publishers, Woonsocket, RI.

Ginslade, T. 2005. Flintlock Fowlers: The First Guns Made in America. Scurlock Publishing Co., Texarkana, TX.

Heckert, W. and Vaughn, D. 1993. The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle: A Lancaster Legend. Science Press, Ephrata, PA.

Kauffman, H. 1960. The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle. Bonanza Books, New York.