- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Horseshoe Curve

St. Louis may have the arch and the name, but in the late 18th and early 19th centuries Pittsburgh was truly the gateway to the West. Located on the Ohio River, once goods reached Pittsburgh there was an all-water route to New Orleans and all intermediate points. However, there was a major obstacle between the ports on the east coast and Pittsburgh: the Appalachians. While not as formidable an impediment as the Rockies, they sweep from Newfoundland to Alabama and form a massive mountainous barrier whose highest peak is 6,685 feet above sea level. The effort to transport goods and people from the ports of New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore resulted in two of the greatest technological advancements of their day. Baltimore had a natural advantage due to its inland location in comparison to the other two. New York and Pennsylvania were driven to develop the Erie Canal and the Horseshoe Curve in an effort to overcome this advantage.

Main Line of Public Works

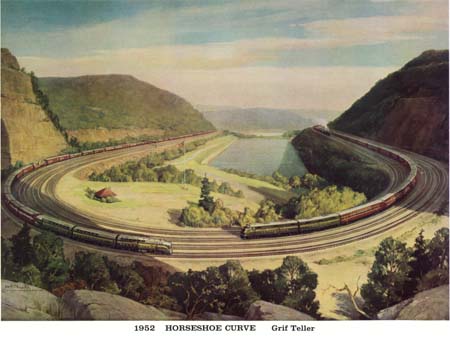

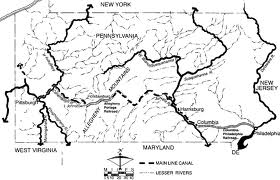

Covered for the most part by virgin woodland the trip across Colonial Pennsylvania took a month on horseback and then later was a 23-day trip by freight wagon traveling old Native American trails. In 1834 the time was cut to four and a half days with the opening of the Main Line of Public Works.

The Main Line of Public Works was a railroad and canal system that moved goods from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. The system consisted of five principal sections:

- Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad: 82 miles from Philadelphia to Columbia, LancasterCounty;

- Eastern Division Canal: 43 miles from Columbia to Duncan’s Island at the mouth of the Juniata River (just north of Harrisburg);

- Juanita Division Canal: 127 miles from Duncan’s Island to Hollidaysburg;

- Allegheny Portage Railroad: 36 miles from Hollidaysburg to Johnstown; and,

- Western Division Canal: 103 miles from Johnstown to Pittsburgh.

Allegheny Portage Railroad

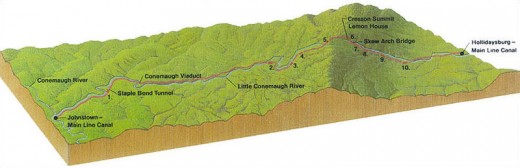

Approximately 36 miles long, the Allegheny Portage Railroad was a series of ten inclines that connected the two canal systems on either side of the Appalachians and played a major role in opening up the interior of the United States to settlement and commerce. Constructed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania the railroad was designed to compete with the Erie Canal, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The railroad used ten inclined planes, five on either side of the summit of the Allegheny Ridge. Going east from Johnstown the vertical ascent was 1,172 feet and west from Hollidaysburg was 1,399 feet. Where the sections were level the barges were drawn by horses and the route included a 900 foot tunnel and a viaduct over the Little Conemaugh River. Typically it took six to seven hours to travel from Hollidaysburg to Johnstown.

Competition with the B&O Railroad

The B&O Railroad was Maryland’s answer to the competition with Pennsylvania and New York. It was a competition to get goods and people transported from their ports into the interior of the country. The B&O had been chartered to build a railroad from Baltimore to the Ohio River and by 1842 had reached Cumberland, Maryland which is about as far west as Altoona. Philadelphia realized they had to find a faster way to get to Pittsburgh if they were going to compete with the B&O.

The Pennsylvania Railroad

In response to the threat from the B&O, Governor Francis R. Shunk signed a bill into law to build a Philadelphia to Pittsburgh railroad. On April 13, 1846 the Pennsylvania Railroad came into being. It was decided by the engineers that the best way to get from one end of Pennsylvania to the other was to go right through the middle and, along the way, they would be able to utilize the Juanita River Valley.

By 1852 the Pennsylvania Railroad was in two segments, the eastern line that ran from Philadelphia to Altoona and the western line that ran from Pittsburgh to Johnstown. In between the segments was the arduous inclined plane system of the Allegheny Portage Railroad which still had to be used to traverse the mountains. The chief engineer of the PRR, John Edgar Thomson, was under pressure to complete the railroad because the B&O was getting closer to completing its own line. He made the decision that the only way to fix the problem presented by the existing system was to by-pass it altogether. He decided to connect the eastern and western segments of the railroad creating a seamless all-rail route from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh.

The PRR had cut a tunnel through the mountain 150 feet below the top of the 1,261 foot high peak. The tunnel was completed without a great deal of difficulty but the problem lay in the steepness of the mountain. For a train to get into the tunnel it would have to gain several feet of altitude very quickly. To accomplish this feet with an inclined plane system would require four or five engine crews per train as well as helper locomotives to push the train up to and through the tunnel. Safety brakes would prevent some accidents but not all. Forgetting about the loss of life and property for the moment, an accident would tie up the tunnel for days if not weeks. Thomson had to come up with something; what he came up with was revolutionary.

Gradient and Curve

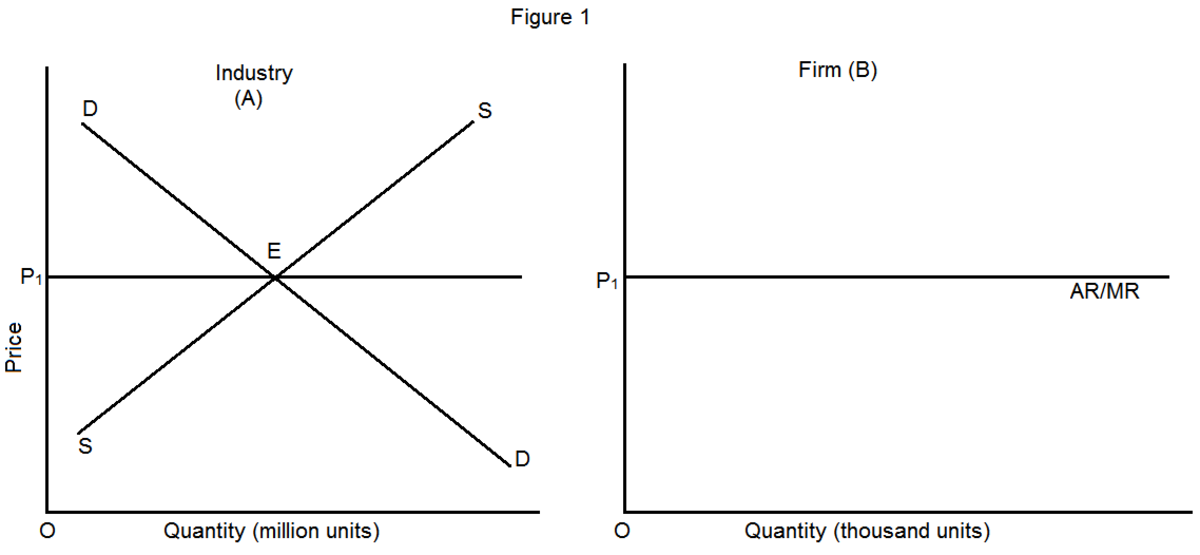

Trains use less energy, speeds are higher, and the wear and tear on equipment is less when railroads are built on straight, level lines. Obviously, land rises and falls, obstacles must be avoided, and the straight, level grade is more the exception than the rule. The basis of any railroad is the track; the basis of any track is the amount of gradient and curve.

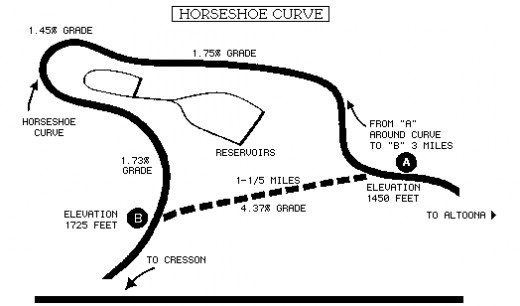

Both gradient and curve are expressed in terms of 100 feet of horizontal distance. If a track rises one foot in elevation over 100 feet of distance it is said to have a grade of 1 percent; if it was to rise two and a half feet it would have a grade of 2.5 percent. On main lines grades are generally 1 percent or less and grades steeper than 2.2 percent are rare. Today, the steepest grade on a main-line in the United States is 3.3 percent in New Mexico.

The impact of grade is significant. A given locomotive can only haul 50% of the tonnage on a .25 percent grade that it can on level track. Grade is much like the weakest link in a chain; a train can only haul as much from point A to point B that it can haul over the steepest segment of grade. One way to compensate for the gradient penalty is the use of helper locomotives to push the train up the grade or, conversely, to help brake the train descending the grade. When helpers aren’t available the train can be cut into two or even three sections to make the climb. All of this takes time and expense, both of which are enemies when competing to move goods over great distances.

Curvature is expressed by the number of degrees traversed by 100 feet of track. Curves of 1 or 2 degrees are the most common on mainline tracks. The sharpest curve a four-axle diesel can take when pulling a train is about 20 degrees. Generally speaking mountainous territory dictates curves of 5 to 10 degrees. The wear on wheels is significant with curves, specifically the flanges. The degree of curve doesn’t matter, all curves wear the flange the same, thus the great desire for tracks to run arrow-straight whenever possible.

Thomson’s Solution

The design Thomson came up with was to gradually raise the grade of the track over distance rather than trying to “climb” the mountain. In order to do this he doubled back on the track, in effect creating a loop, allowing the track to gradually ascend. Instead of the 8 to 10 percent grade of the inclined planes previously utilized, Thomson’s new track would have a maximum 1.8 percent grade.

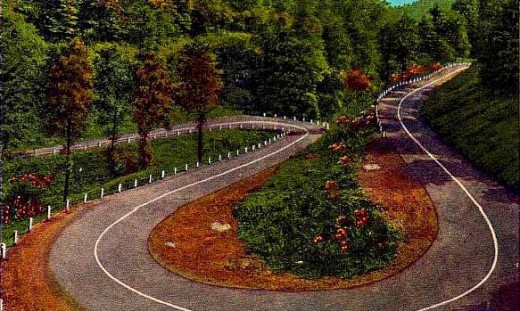

In its final form Horseshoe Curve was 1,800 feet across and a half-mile long with the west side being 122 feet higher than the east side. Trains traveling east to west would ascending and those traveling west to east would be descending.

The Horseshoe Curve represents what imagination, perseverance, and vision can accomplish. Opened on February 15, 1854, the Horseshoe Curve with its curving, steadily climbing track has never been improved upon. When it opened travel time was reduced to 15 hours between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and the fare was reduced from $9.50 to $8.00 for a one-way ticket. In addition to its capacity for transporting goods, passengers could now be transported from one end of the state to the other without having to change trains.

In the 1900s the PRR was the leader of America’s railroads, mostly due to the Horseshoe Curve. It was the largest, wealthiest, and single most powerful railroad in the United States carrying 10% of all freight traffic in America and 20% of all passenger traffic.

As we moved further into the 20th century the railroad would begin to lose ground to trucking and the interstate highway system. However, the railroad and specifically the Horseshoe Curve were still important enough to the United States that in June 1942 highly-trained Nazi saboteurs were smuggled into the country by submarine to destroy infrastructure. Prominent among their targets was the Horseshoe Curve. By 1954, the centennial of the Curve, 25,500 freight trains and 2 million passengers a year traveled up and around the mountains.

Today

The last half of the 20th century saw the decline of railroads. The PRR was merged with the New York Central to form Penn Central which resulted in, at the time it occurred, the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. Out of the ashes of the Penn Central Congress created Amtrak and Conrail, both of whom exist today. There are a limited number of trains that use the Horseshoe Curve but it remains active and an important part of America’s commerce.