- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

How the 25th Amendment to the Constitution Solved a 150-Year-Old Problem

One of the wonderful things about the Constitution of the United States is that it can be self-correcting. Article V outlines the process by which the Constitution can be amended. While many of the 27 amendments can be thought of as expansions of the Constitution (those extending the right to vote to women and to 18-year-olds, for example), there are others like the 25th that can be viewed as corrective measures addressing flaws in the original document.

This hub traces the problems that led to the passage of the 25th Amendment, which deals with presidential succession.

A Precedent, Yes, But a President? Maybe Not

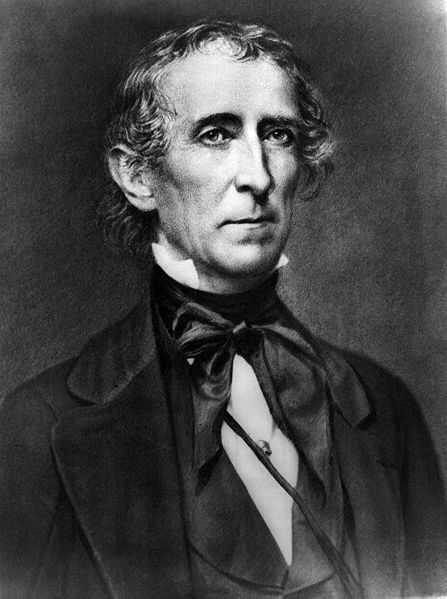

In April 1841, a month after President William Henry Harrison was inaugurated, he died. When his vice president, John Tyler, heard the news of Harrison's demise, he said he guessed that made him the president now.

Others said not so fast. They wanted to check the Constitution to be sure.

It turned out the Constitution was a bit murky on the subject of what would happen if the President should die while in office. Article 2, Section 1 stated that if a president died or was otherwise unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, "the same shall devolve on the Vice President."

But what exactly did that statement mean? Did "the same" indicate that just the powers and duties would devolve to the vice president? Or did it mean that the title, the fancy house, the pomp and circumstance -- basically the whole shooting match -- would devolve to him as well?

Tyler believed it was definitely the latter, and acted accordingly. He hurried to Washington from his home in Williamsburg, Virginia; took the oath of office (even though he believed his vice-preidential oath was sufficient); moved into the Executive Mansion; and started chairing Cabinet meetings. He refused to be addressed as Acting President, returning unopened any correspondence so designated. Going full-bore in this way, even though the Constitution didn't expressly give Tyler permission to do so, became known as the Tyler Precedent.

Tyler's move also created a vacancy in the vice president's office, which would last for the remainder of Harrison's term -- just a month shy of four years.

It was not the first time that America had been without a vice president. In 1812 George Clinton, vice president under James Madison, died. The chair remained empty until 1813, when Madison's second vice president, Elbridge Gerry, was sworn in. Then in 1814 Gerry died, leaving the seat empty once again. Madison was thus the only president to have the misfortune of having both of his vice presidents die on him.

In 1832, the Office of the Vice President also became vacant when Andrew Jackson's vice president, John C. Calhoun resigned to become a Senator. In that case, however, it was only a few months before the inauguration of Calhoun's successor, Martin Van Buren.

Is Anyone Sitting Here?

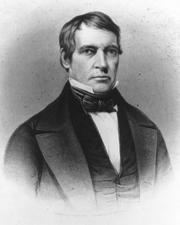

After John Tyler, the next vice president to jump into the presidential chair was Millard Fillmore, who stepped up when President Zachary Taylor died in 1850. Fillmore did not win his party's nomination, however, and the election of 1852 went to Democrat Franklin Pierce. Pierce's running mate, William Rufus Devane King, was in fact not a well man. Having gone to Cuba for health reasons, he ended up taking the oath in Havana rather than in Washington. King returned to the states, but shortly after that he died. Thus except for the two brief months that King served, there was no vice president at all from the middle of 1850 until March of 1857.

Between 1865 and 1901 three presidents were assassinated -- Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield, and William McKinley. In all three instances, the President was shot near the beginning of his term. Thus when Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt respectively ascended to the presidential chair, the vice president's seat remained empty for nearly four years. With Arthur, that could have been a problem. In 1882 he learned that he had Bright's Disease -- a potentially fatal illness. Had he died before completing Garfield's term, it would have been the first time the president pro tempore of the Senate would have had to fill in for the president. Fortunately, that did not happen.

The vice president's chair was unoccupied three other times between 1865 and 1901. In 1875, Ulysses S. Grant's second vice president, Henry Wilson died of a stroke -- his second in two years. In 1885, after serving less than a year, Thomas A. Hendricks, vice president under Grover Cleveland, passed away. And in 1899 McKinley's first vice president, Garret A. Hobart, also succumbed.

At Last a Remedy

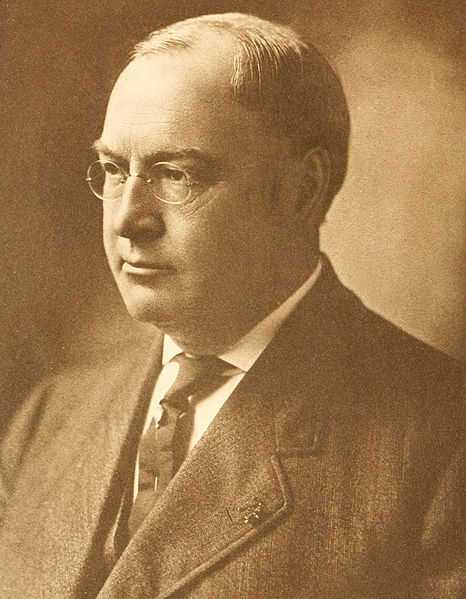

The vice presidential chair didn't sit empty nearly as often in the Twentieth Century as it had in the Nineteenth. Only once in the Twentieth Century did a vice president die while in office. That was James Schoolcraft Sherman, vice president under William Howard Taft. Sherman died at perhaps the worst possible time -- a week before the election of 1912, where Taft tried and failed to keep his job.

The next president after McKinley to die while in office was Warren G. Harding in 1923. Though some mystery surrounds his death, most historians believe he died of natural causes. He was replaced by vice president Calvin Coolidge. Twenty-two years later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died and was replaced by his third vice president, Harry S Truman. Truman's was another case where the vice presidential chair sat vacant for a relatively long time, as FDR had died only a few months into his fourth term.

If you've been counting, that makes a total of 15 vice presidential vacancies between 1812 and 1945.

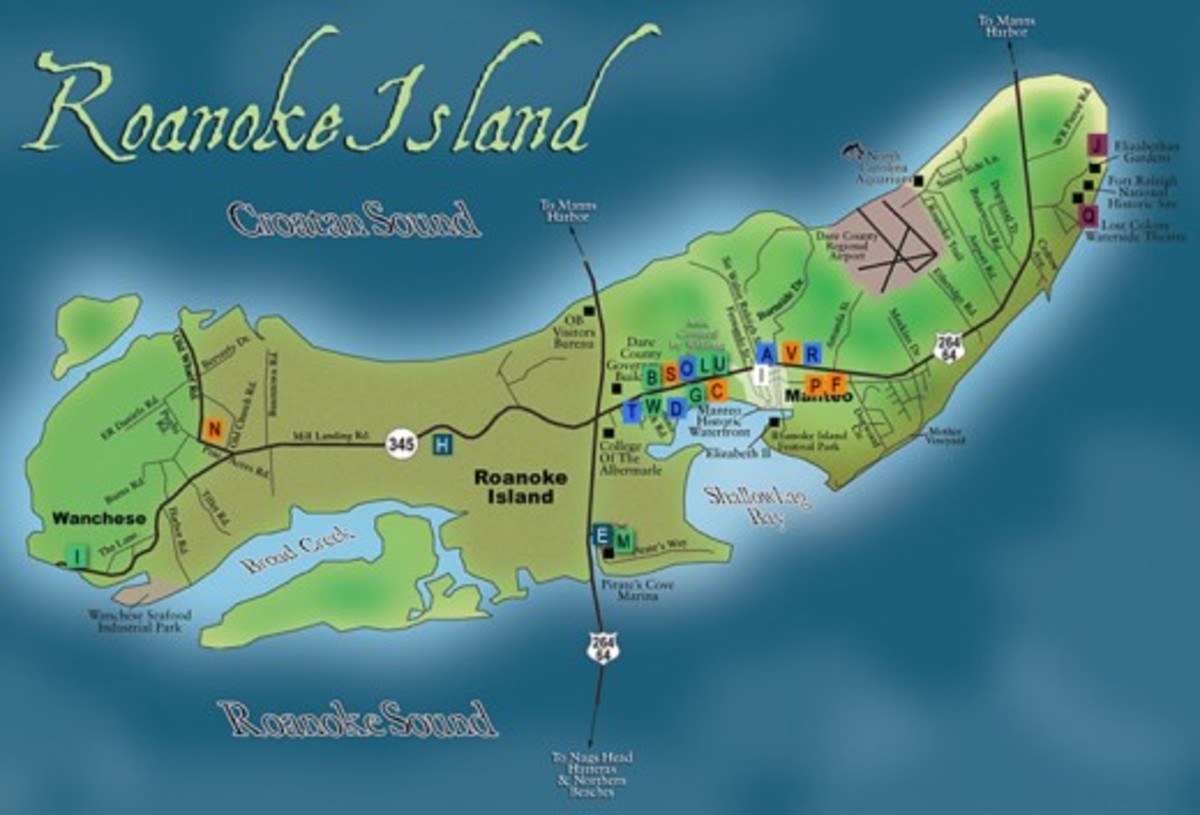

The assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963 marked the fourth time a President had been removed by the bullet. Lyndon B. Johnson ascended to the presidential chair, leaving the country once again without a vice president, for a little over a year. Though Kennedy's murder was not the only impetus for a Constitutional amendment regarding succession (a measure quite like it had been proposed prior to Kennedy's election), the assassination did help to crystallize the idea. What was to become the 25th Amendment passed Congress in July of 1965 and was ratified by the requisite number of states by February 1967.

At its heart, the 25th Amendment sides with John Tyler. Not merely the powers and the duties of the president but also the office devolves on the vice president. The amendment states clearly "The Vice President shall become President." But the amendment has two other important provisions as well. One is that if the vice president's chair becomes vacant for any reason, the president can nominate a new vice president subject to the consent of a majority of both houses of Congress. Also, the amendment allows for the possibility of the vice president becoming an acting president should the president become incapacitated for some reason, such as illness. The idea here is that once the president is well, he can resume his duties again. Prior to the 25th Amendment, if a president were to relinquish his duties and assign them to the vice president, there would be no legal way for him to get them back

It Works!

The 25th Amendment was put to the test in the mid-1970s during the administration of Richard Nixon. In 1973 Nixon's vice president Spiro Agnew resigned as a result of a criminal investigation. Under the provisions of the 25th Amendment, Nixon nominated Representative Gerald R. Ford of Michigan to replace Agnew. Ford was confirmed by both houses and sworn in as vice president in December 1973. In August 1974 Nixon also resigned and Ford stepped into the president's chair. To fill the new vacancy in the vice president's chair, Ford nominated former New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, who was sworn in as vice president on December 19, 1974. Thus from 1974 to 1977, neither the President nor the Vice President of the United States had been elected to either office.

A 150-year old problem had been solved. No longer would America be without a vice president for three-, four- or seven-year stretches. The Amendment process proved its worth.