How to Write a Syllabus

Welcome to my world, please take out a #2 pencil.

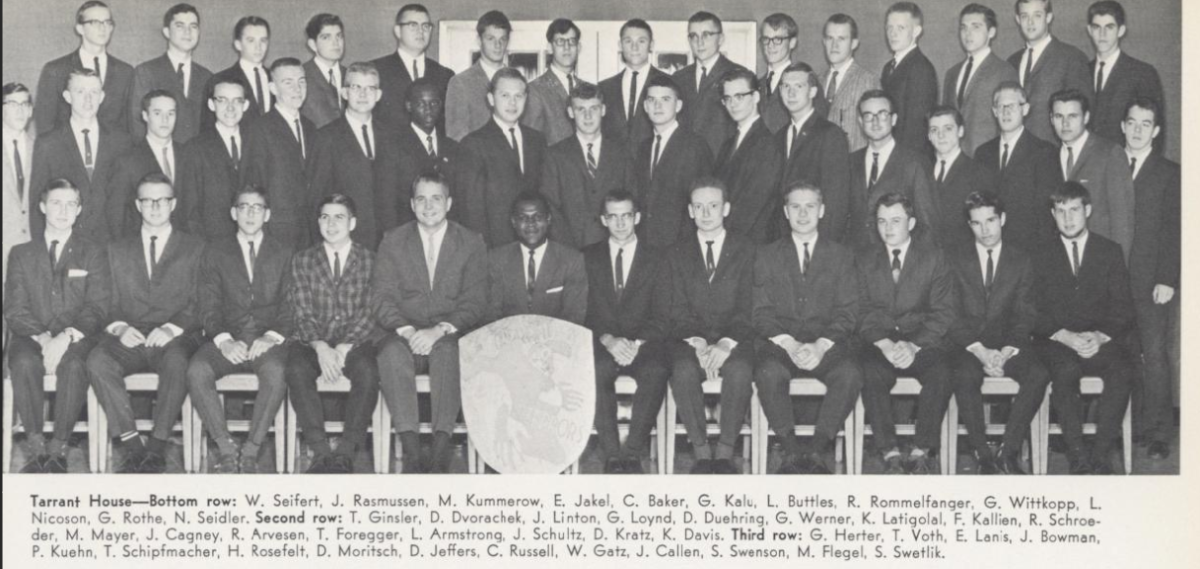

As a college professor, I am often asked "How in the world did you become a college professor?" It is my considered opinion that the smart people already had real jobs. Regardless of how I got here, somehow I am now responsible for composing syllabi for the courses they make me teach.

The word syllabus is Latin for "document that will never be read." It contains a broad overview of how a specific class will proceed. We college teachers work long and hard each semester to polish and refine our syllabi to meet the needs of modern students. It makes us feel better and it kills a little time between faculty meetings.

What's supposed to be in it?

A typical syllabus typically begins with identifying information. A quick scan at the top of the first page should reveal course title/number, section, meeting time, location, and semester. This crucial information allows students to understand precisely what they will be ignoring.

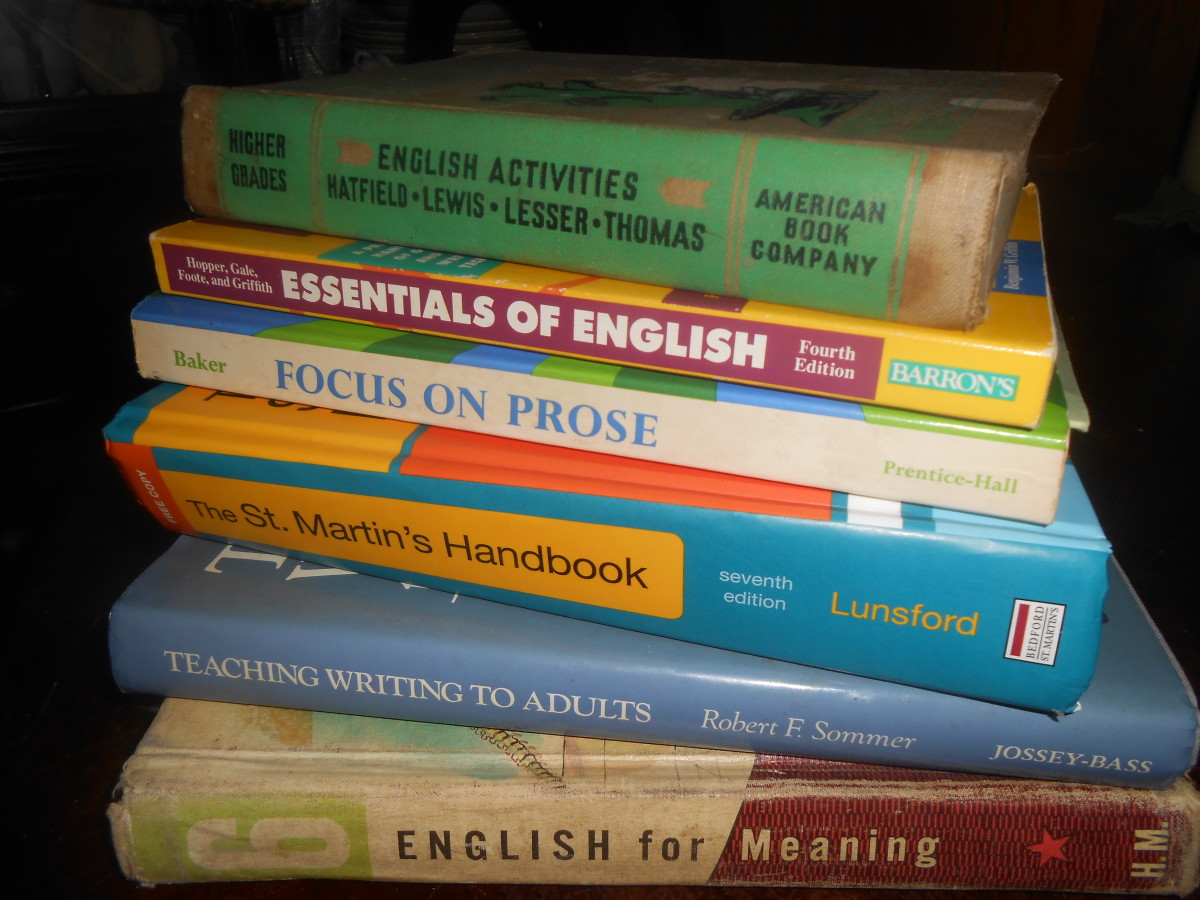

Following that should be book information. Most college courses require textbooks that effectively double the cost of tuition: it is therefore crucial to define the proper version and edition of the expected book. Federal law now requires colleges to publish book information before the semester begins. Students may then obtain copies from alternate sources. It's a really good thing when the syllabus actually matches what the college is publishing. I find that including a picture of the book cover, as well as the ISBN, greatly aids students in their search to locate online copies.

SLOs

SLOs, or Student Learning Outcomes, are the foundation of the course. Each SLO represents a skill or talent that the student should acquire during the semester. A comprehensive set of well-written SLOs shines like a jewel and should be prominently displayed in a syllabus. Hordes of educators working in concert with experienced and caring administrators struggle mightily to compose these bits of wisdom defining precisely what will be generally covered in the course. Sometimes we follow them.

Grading Policy

Most institutions of higher learning insist that professors assign grades, much to the consternation of students. It is wise to clearly define how grades will be calculated before assignments are assigned. Students appreciate the opportunity to look back upon a semester of heartache and realize that they earned a 59% in the course because they never turned in any homework. It's nice to see everything laid out in black and white.

Withdrawal Policy

Pragmatism dictates that a syllabus clearly explains what to do in the event of catastrophic failure. We want everyone to get a trophy, but sometimes a chronic lack of attendance gets in the way. Students need to know how to bail out.

Withdrawing from a class has become complicated, surprisingly, with the advent of socially-funded higher education. A student borrowing tuition money from the government must navigate a carefully constructed bureaucracy: if they simply stop showing up, they might actually have to pay back their loans.

Reading Schedule

As previously noted, textbooks play a prominent role in college courses. They consume valuable resources such as financial aid and space in the backpack. Many college professors attempt to integrate the textbook into the course by assigning reading. We enumerate the Reading Schedule in the syllabus so each student may achieve maximum benefit from the material in the book.

We understand that students benefit from reading the book before they come to class. We prefer not to stand in front of the assembled masses and read from the textbook. It's our job to embellish and clarify what they already read.

During class, we may relate a real-world anecdote paralleling the assigned reading. I personally enjoy discussing current events that dovetail with what the students read before they came to class.

Whoop, there it is.

Thank you for reading. You are now ready for the final exam.