Of Matrix and Blitzkrieg: How The Best Teachers Teach

SUMMARY: SOME WAYS ARE MORE EFFICIENT

Kids have to be in the classroom.

Why not make the experience as fun and productive as possible?

LET'S DO WHAT WORKS BEST

I’ll start by admitting that I’m not much interested in theories and ideologies. My mind is hopelessly pragmatic and empirical. I am fascinated by what works.

Modern educators don’t seem sufficiently interested in head-to-head comparative testing. Fifty teachers try Plan A, fifty teachers try Plan B, fifty teachers try Plan C. At the end of a month or a year, use the available tests to see which Plan works best. Is anybody doing this? Another problem is that some elite educators are deeply interested ONLY in theory and ideology, with the results that practical results are downplayed.

But let us suppose that a school is actually interested in teaching with maximum efficiency. What kind of techniques would the teachers at this school use?

MATRIX TEACHING

Generally, the best way to teach anything is to teach it in relation to something else. An atom spins like a top on its axis. As does a planet. Oh, I get it!

If Fact A and Fact B are presented as part of a cluster of related information, these facts will be more quickly understood and more easily retained in memory. This simple insight is the basis of what I call matrix teaching.

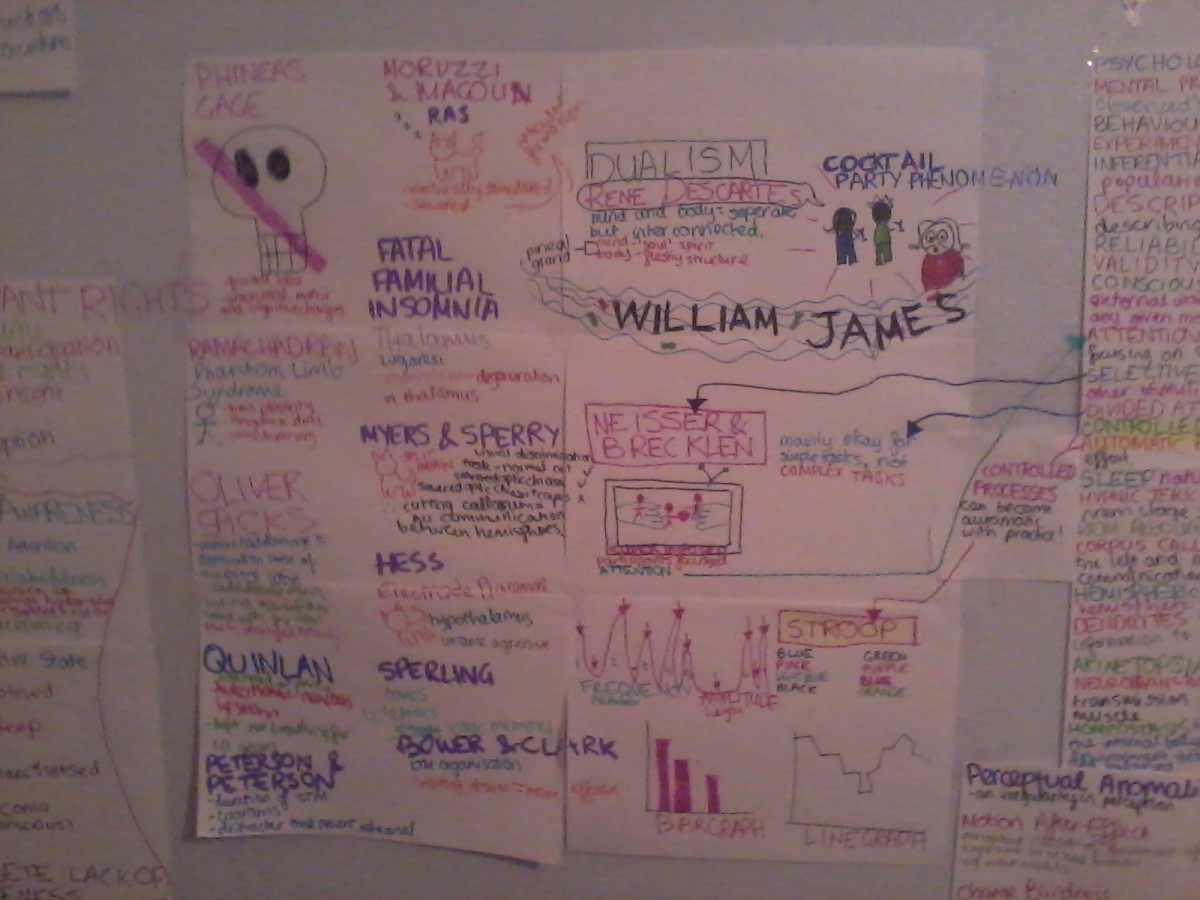

Parables, metaphors and analogies are obvious examples of matrices. Photographs, blueprints, circuits, maps, and models are as well. One thing is taught via some other thing. The more other things, the better!

Suppose you want to remember to make a phone call, and you tie a yellow ribbon around your finger. You have embedded that phone call in a simple 2-element matrix. As we know, mnemonic devices work. But note that in this example, the yellow ribbon is itself trivial; red would work as well and be just as trivial.

The triumph of matrix teaching occurs when aspects of geography are used to teach history, when science is intermixed with music, when poetry is an actor in political study...when the facts being taught are linked together into larger structures and, by artful design, students are able to learn the most in the shortest time.

Speaking of mnemonic devices, I was fascinated to find that students in England were told to invent sentences that would help them remember the nine planets in order from the sun (e.g., My Very Early Morning...). I love this! Astronomy meets creative writing meets vocabulary building meets spelling drill. That’s extreme matrix teaching!

MEMORY IS MASTERY

Progressive educators tirelessly campaign against “rote memorization.” Carried to the usual extremes, this attitude quickly becomes stupid and destructive. The ultimate formulation--“They can look it up”--is downright pernicious. As though somebody reading a newspaper or hearing TV news about a civil war in Spain is going to run to an encyclopedia to find out what a civil war is. And what Spain is!

Fortunately, more and more schools and teachers are waking to the truth: memory is mastery. Life’s so much simpler when we have a lot of vital information handy in our own personal database.

Unfortunately, even when modern educators decide they actually want to teach something, they invariably do this in the way that will be least efficient. They proceed in exactly the opposite way from that suggested by matrix teaching.

The strategy commonly used is to take some fairly simple matter and pulverize it into ever smaller pieces. And then to dawdle for a long time over each of these pieces, reducing the whole school experience to one of horrific tedium. At the end of this lengthy and disjointed process, the student is supposed to retain all the unstructured information and to somehow reassemble all the scattered bits and pieces into a coherent structure. Even the typical adult would have difficulty in deducing what that structure is supposed to be. The typical child doesn’t have a prayer.

If you wish to reflect upon a huge and hugely wasteful example of the counterproductive way to do things, consider the look-say method of teaching children how to read. Look-say throws away the matrix--i.e., phonetics--that links most English vocabulary. English is broken into thousands of mysterious little symbols or logos. The children are invited to rummage among these fragments. No true reading occurs. Nothing else is learned--for example, the beauty of poetry, the pleasure of a story, or facts from history. And this idiotic waste does not go on for weeks or months. But for years. (Keep in mind that schools traditionally taught all children to read by the end of the first grade.)

Matrix teaching--isn’t it obvious?--would use poetry, history and science to teach reading; and reading to teach poetry, history and science; and math and art to teach the others! The goal is to make school easier and more fun.

BLITZKRIEG

Dare I introduce warfare into such a genteel essay? The German concept of blitzkrieg warfare does provide an interesting analogy. The idea was to strike with maximum force at the enemy’s weakest point. In the matter of students, the weakest point is whatever they already know or whatever they would most like to know.

Blitzkrieg further demanded that the attack proceed as far as possible. Develop momentum and keep it moving. Then you come back and deal with the pockets of resistance. In the matter of students, you go beyond what the majority can handle and then you come back and attack what isn’t clear. Then you do it again, from a different direction and with a new matrix. And again.

Suppose the subject is teeth. At the least you would want to have a real tooth, an x-ray of a tooth, a big cross-sectional drawing of a tooth, and a skull with teeth in it. Isn’t each of these just more of the same? Not at all. Each item is part of a blitzkrieg, and a widening matrix. What else can we add? How about quotations from dentists about their most unusual cases and how they must learn to work in a mirror? How about stories from students about trips to the dentist? How about pictures of diseased teeth? How about some shiny dentures? And how about pictures of birds showing that they have beaks, not teeth? Is there a class of fourth graders that couldn’t absorb all of this in an hour? After all, they have teeth, they know a lot about their own teeth! That’s the weak point of the enemy line.

Then, the next day, you do it all over, but with different points of emphasis. Then you skip a week and come back and do it all again. Note that we’ve used up only three hours. At the end of this blitzkrieg, I predict, these young children would know more about dentistry than the average adult.

Finally, you don’t expect students to retain all of this. You hope they’ll retain a half or a third. And that’s what you test on. And almost everyone gets a good grade!

The genius of the blitzkrieg is what some might think is a sort of overkill. Not so. You can never know what image, what tidbit, what off-the-wall quote will be the one that pierces a particular child to the heart, and makes the whole matrix organize itself logically in the child’s mind. I still remember the day (I was about 12) when I saw an X-ray of an infant’s skull (possibly it was an embryo’s skull), and I saw with total astonishment the stacked array of perfect little teeth, already formed, waiting there in the bone. Somehow, the top row of teeth would actually navigate downward through solid bone and end up perfectly positioned in the mouth. I kept mumbling, “I can’t believe this...they are all there!” And for the rest of my life, when a dentist said that a tooth might move in some way, I said, “Yes, I get that part.”

Modern educators don’t believe in blitzkriegs. They like the teeny-tiny attack. They create very short lists of things an ordinary fourth grader should know. They hammer away, item by item, over hours and days, at this list. Everyone is bored. Nobody sees a bigger picture. The typical student ends up knowing only part of what was a short list to begin with. One thing is for sure: students can never know more than that. Mediocrity is engineered in.

(“Teeny-tiny” presumes that at least some teaching is taking place. Next came Constructivism, which forbids even that much. Of which more in a moment.)

GOLDEN RULE

To understand the best ways to teach anything, simply ask how you would like to be taught that subject.

It’s guaranteed: you do not want to wallow in a lot of unrelated details without first having a sense of what’s going on. You want the teacher to lay out the big picture, fill in lots of juicy details, and then explain what you just learned.

Another way to grasp the best ways to teach is to imagine how adults normally teach children, around the home or the campfire, whether now or thousand of years ago. Basically, adults will simply (and sincerely) tell the whole story, simplified perhaps but complete, and wait for the child to ask questions, which are promptly answered, and you go from there.

Many educators today won’t tell the whole story, only particles. And they won’t answer questions because they don’t want to impose their answers on the child. So that what might take 20 minutes if the adult is acting in good faith might take hours or days if the adult has been trained at non-teaching in a school for teachers.

As part of their belief in leveling and collectivism, progressive educators do not actually want to teach too much, because some students will move out in front of others. So the liberal paradigm seems to be to keep everyone churning sweatily in the same patch of gravel for as long as possible. Equal, yes. Equally ignorant.

PUTTING ON THE BLITZ

Suppose we want to teach children about the Grand Canyon. I’m guessing that modern educators could turn this into a dozen class units. I wouldn’t be surprised if they started at the beginning of time, when the land was flat and a trickle of water was beginning to form into what would be the Colorado River in another 200 million years. Hour by hour we would wend our weary way to the Grand Canyon as it is today. Anybody still awake?

But what is the optimal way? We take the kids to the edge and say, “Look at this!!!” If we’re not in Arizona, we do as close to this ideal as possible with films, photos, digital reconstructions, etc. “Total immersion” is the phrase Berlitz uses to describe its language instructions. We should totally immerse those kids in the Grand Canyon--that’s the optimum. Everybody loves looking at the Grand Canyon. The blitzkrieg is obvious: show them the thing. Don’t parcel it out, don’t mince around. No slow-motion strip tease. Just do it....Then we call their attention to this or that feature. We explore details. Always coming back to the big picture, which is the canyon itself.

PRIOR KNOWLEDGE AND THE FOLLY OF CONSTRUCTIVISM

One cute device they’ve come up with: students, we are solemnly assured, don’t need “a sage on a stage.” They need “a guide by their side.”

The students and this guide, according to Constructivism, are then supposed to reinvent and rediscover ten thousand years of mathematics, history, science, geography, etc. It’s quite silly.

Educators say this method is Socratic, which it ain’t. Socrates was exploring elusive moral questions--what is happiness, how should we live, that kind of thing. The fourth grade teacher is merely explaining how Columbus happened to discover America. Basic facts.

Constructivism says teachers can’t teach what they know. They must find out what each kid knows, and then build on this prior knowledge. Calculate how much time will be wasted as teachers discover the prior knowledge of each kid in the class. Visualize how the teacher’s focus and delivery will be fragmented, and how the classroom will be effectively divided into twenty micro-classrooms. Constructivism is in play throughout most subjects in most schools. It’s easy to see how this thing could shut down education altogether. I suspect that is its purpose.

Now imagine yourself, as an adult, going to a lecture on Japanese Art or Brazilian History and the lecturer refuses to tell you anything about the announced topic, instead demanding to know, “What do you think about X and Y?” These being the very things you came to the lecture to learn about! I predict you would be really, really irate. Students can’t know so clearly that they are being shortchanged. They are probably going to feel sullen and confused.

This “guide by their side” business is another pretext for teaching as little as possible. Prior knowledge is usually irrelevant. What we must be obsessed with is new knowledge.

EFFICIENCY AND ERGONOMICS

Let us suppose that you are interested in efficiency. Here are some examples of what matrix teaching suggests to me:

A) Classrooms must have, of course, a large map of the world and of the USA. Every story in the newspaper, every bit of history that is studied, every holiday, every scientific discovery is an occasion for the teacher to step to one of those maps and weave together the event, the place, the year, the people involved, and whatever broader truths can be worked into each matrix. Any teacher that isn’t touching both maps every day isn’t trying very hard.

B) Discussions of arithmetic and math are accompanied by numbers on the blackboard, objects on the desk, pictures on the computer, and whatever else a teacher can dream up in each case. Picture a three-ring circus where basically the same act is unfolding in each ring; so you see it over and over but with new details each second.

C) Mentioning a circus is not accidental. It’s vital that children have fun, that they smile and laugh, that they hardly know they are being educated.

D) It’s most efficient to teach vocabulary words in large, related groups. Verbs from sports. Words that come from French. Words that exhibit onomatopoeia. Words that are colors. Words that rhyme. Words that are commonly mispronounced. Words that start with X.

Words could be taught as part of popular songs, ad slogans, cereal boxes, signs near the school, labels on products used by the children. It’s all so obvious. But I’ll bet that many people will read this with amazement, and therein lies the great sadness.

Teaching roots of individual words is good, but common roots are much better. I still remember how excited I was when I first encountered (in a book) what must be one of the largest group of cognate words. They are all descended from the same Sanskrit root. Such a list--regal, rigid, correction, regulation, direction, Reginald, dirigible, rigor and about 25 more. The common denominator is an rg sound that in Sanskrit means straight, as in to plow a straight furrow. All the words pertain to strictness, rectitude and proper governance.

"3: Latin Lives On" on Improve-Education.org describes another surprising list that can be taught in one salvo--333 common words that are pure Latin-English.

E) Science/chemistry/biology/physics might best be taught, in the early years, as one big matrix--Things We Can Observe. Everything should be explained in relation to objects in the classroom, the kitchen, or the school yard, and in relation to the children’s lives and experiences. (See related video below.)

In sum, nothing is taught in a vacuum. Everything is taught as an aspect of something else, as part of a matrix.

IN CONCLUSION

Ultimate teaching is whatever works best, as revealed by all the standard tests, follow-up interviews, and comparisons between different class rooms and schools. At the moment we have too many people in this game who are not interested in what works. Indeed, they seem positively and ghoulishly fascinated by what clearly does not work. Ideology does that to people.

We need more kinds of schools and more competition--friendly competition that is sincerely aimed at finding the really clever way of teaching each subject. But must of all we need good faith, that is, total sincerity on the part of teachers and administrators.

THE WRITER

Bruce Deitrick Price is an author, artist, poet, and education reformer. He founded Improve-Education.org in 2005. He has always been fascinated by the challenge of finding the most enjoyable and efficient ways to organize classrooms. His sense of American public education is that the people in charge don't aim high and don't try to find the most efficient approaches. Price has hundreds of articles and videos on the web; and they can all be summed up in a few words: facts are fun and knowledge is power.