Iain McGilchrist's The Master and His Emissary

Modern Madness Explained

A review of Iain McGilchrist's The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (544 pages, Yale University Press; October 30, 2009)

If you and I were to enter into a conversation about the state of affairs and I were to proclaim (as I often do) that ‘the whole world has gone insane’, you would probably nod your head in agreement, taking my statement to be metaphorical.

If however I were to insist on the literal truth of what I was saying, you would likely back away, and begin to wonder about my own mental health.

But if psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist is to be believed, to characterize the modern human world—as presented by most any current event in the news—as ‘insane’ or (to use a slightly less loaded term) ‘unbalanced’ is to make a fairly literal diagnosis of our collective mental health.

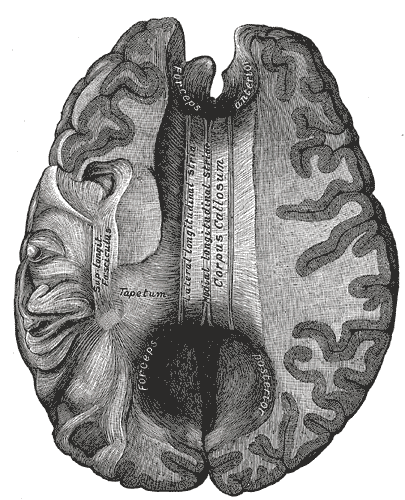

McGilchrist makes a compelling case in his book The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. The subject of the book is the nature of human consciousness—as revealed through psychology and psychiatry, as well as philosophy, art, and history—in relation to the anatomy of the human brain, whose cerebral cortex consists of two separate bilateral hemispheres that communicate with one another via a tract of nerves called the corpus callosum. The title comes from a parable related at the end of the Introduction, which serves to metaphorically frame the book’s thesis (p. 14):

“There is a story in Nietzsche that goes something like this. There was once a wise spiritual master, who was the ruler of a small but prosperous domain, and who was known for his selfless devotion to his people. As his people flourished and grew in number, the bounds of this small domain spread; and with it the need to trust implicitly the emissaries he sent to ensure the safety of its ever more distant parts. It was not just that it was impossible for him personally to order all that needed to be dealt with: as he wisely saw, he needed to keep his distance from, and remain ignorant of, such concerns. And so he nurtured and trained carefully his emissaries, in order that they could be trusted. Eventually, however, his cleverest and most ambitious vizier, the one he most trusted to do his work, began to see himself as the master, and used his position to advance his own wealth and influence. He saw his master’s temperance and forbearance as weakness, not wisdom, and on his missions on the master’s behalf, adopted his mantle as his own—the emissary became contemptuous of his master. And so it came about that the master was usurped, the people were duped, the domain became a tyranny; and eventually it collapsed in ruins.

“The meaning of this story is as old as humanity, and resonates far from the sphere of political history. I believe, in fact, that it helps us understand something taking place inside ourselves, inside our very brains, and played out in the cultural history of the West, particularly over the last 500 years or so. Why I believe so forms the subject of this book. I hold that, like the Master and his emissary in the story, though the cerebral hemispheres should co-operate, they have for some time been in a state of conflict. The subsequent battles between them are recorded in the history of philosophy, and played out in the seismic shifts that characterise the history of Western culture. At present the domain—our civilization—finds itself in the hands of the vizier, who, however gifted, is effectively an ambitious regional bureaucrat with his own interests at heart. Meanwhile the Master, the one whose wisdom gave the people peace and security, is led away in chains. The Master is betrayed by his emissary.”

The wise Master in McGilchrist’s account is the right cerebral hemisphere, while the usurping emissary the left.

The Master and his Emissary is, in a way, a mirror image of Julian Jaynes's masterpiece The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and is just as engaging, and as remarkable in its breadth of scholarship and insight into the nature of subjective human experience.

Like Jaynes, McGilchrist seeks to understand how experience relates to the fact that the bilateral (left and right) hemispheres of the brain are not symmetric, but rather structurally and functionally differentiated (which is true not only for humans, but also for other vertebrates, including birds). Both authors cover much of the same empirical territory, reviewing myriad case studies of subjects and patients with lesions or deficits in one hemisphere or the other, as well as Roger Sperry’s Nobel-prize winning research with split-brained patients (who had had the corpus callosum surgically severed as treatment for epilepsy) showing that the two hemispheres work independently in parallel. The upshot of all this is that, as Sperry himself noted, the two halves of the human brain have quite different and somewhat opposing ways of attending to, and hence consciously experiencing, the world.

Whereas the left hemisphere is specialized for attention focused on completing the task ‘at hand’, and hence that which is well-defined, certain, and explicit, the right hemisphere is widely vigilant, attending to the ever-changing gestalt (‘big picture’) and the ‘other’, and hence that which is vague, uncertain, and implicit. The well-known localization of linguistic facility to the left hemisphere makes sense given the latter’s propensity for focused manipulation and control. But the right hemisphere also understands language, and is in fact the seat of poetry, and accordingly, our ability to create and use metaphor as a way of relating to the world. The left hemisphere, in contrast, tends to use and interpret language literally. In general, it can be said that our experience of the world is created in (or by) the right hemisphere, and becomes routinized in (or by) the left hemisphere. Thus, words that are initially coined as metaphors (e.g., the word ‘comprehend’) are interpreted in increasingly literal ways as they become routinized (turned into cliché) in the left hemisphere, eventually losing their implicit metaphorical connotations.

Where McGilchrist parts ways with Jaynes is in the interpretation of how this played into the evolutionary development of human consciousness. Whereas Jaynes views consciousness as having emerged via the increased integration of the hemispheres (‘breakdown of the bicameral mind’), McGilchrist argues that the opposite actually occurred: i.e., consciousness developed via an increased functional separation (a dis-integration) of the hemispheres, which imposed a useful distance between immediate (right hemispheric) and linguistically represented (left hemispheric) experience. Accordingly, McGilchrist has a different take on schizophrenia, which Jaynes saw as a throwback to the mentality of our ‘bicameral-minded’ ancestors. The problem with that idea is that schizophrenia is a relatively modern disorder that has actually been increasing in prevalence over the past two centuries, and may not even have existed before the eighteenth century. Moreover, it is a complex disorder that involves much more than auditory hallucinations (which McGilchrist grants may well have been experienced by the ancients), and it is difficult to imagine that it would allow for coherent social functioning—even, as Jaynes proposed, in a culture built around those hallucinations.

Following the line of argument articulated by Louis A. Sass in Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature, and Thought, McGilchrist holds that schizophrenia is not a regression to a less rational, more emotional state (as traditionally held), but rather a form of hyper-rational consciousness (or hyperconsciousness) produced by an imbalance toward the distancing (and ultimately alienating) left-brain mode of attention, which has been growing increasingly dominant over the past three centuries. On the heels of the Enlightenment, this trend was greatly accelerated by the Industrial Revolution, a product of the left-brain mode of attention that established a positive feedback loop favoring the latter’s runaway ascendancy. From this perspective then, the increasing prevalence of schizophrenia (and of other modern psychological disorders that manifest a strong imbalance toward the left hemisphere, such as autism) can be interpreted as a symptom of a general developmental trend entraining the consciousness of civilized humanity as a whole.

This of course is not a good thing. The focused, reductionist/literalist mode of attention favored by the left hemisphere is not conducive to breaking out of habitual ways of being—quite the opposite in fact. Its tunnel vision is good for discerning and communicating the technical details of specific problems, but not for perceiving, much less appreciating, either the context that produced those problems, or the unintended consequences of the short-term solutions it devises to address them. Without the more ‘pessimistic’ vigilance of the right hemisphere to keep it in check, the cocksure ‘can do’ attitude of the left hemisphere encourages an overly optimistic outlook that engenders hubris. McGilchrist thus concludes Part 1 (p. 237):

“So if I am right, that the story of the Western world is one of increasing left-hemisphere domination, we would not expect insight to be the key note. Instead we would expect a sort of insouciant optimism, the sleepwalker whistling a happy tune as he ambles towards the abyss.”

It is important to emphasize, as does McGilchrist throughout his book, that the two hemispheres function together as an integrated whole—they are both needed for human survival and mental health. But because of their anatomical and functional differentiation, they are not equivalent or redundant. And that being the case, it is important that we understand what each hemisphere is functionally specialized for. Although all generalizations, including those made in the book, have exceptions (which McGilchrist acknowledges), the evidence indicates that the right hemisphere is specialized for presentation, and the left hemisphere for re-presentation, of experience. The right hemisphere is therefore primary, the font of intuition (and music, which McGilchrist argues is the precursor to language), which is then secondarily broken down and analyzed (rationalized) by the linguistically facile left hemisphere.

The problem is that these different ways of attending to the world are to some extent oppositional, and often to come into conflict. And there is a troubling developmental tendency, especially pronounced in modern times, for the ‘rational’ mindset of the left hemisphere to become disparaging and even contemptuous of the ‘intuitive’ mindset of the right. As a result the ‘emissary’ comes to think it knows better than its ‘Master’, to the detriment of all. McGilchrist builds the case for these claims in ‘Part 1: The Divided Brain’, by way of six chapters: “Asymmetry and the Brain”; “What do the Two Hemispheres ‘Do’?”; “Language, Truth and Music”; “The Nature of the Two Worlds”, “The Primacy of the Right Hemisphere”, and “The Triumph of the Left Hemispere”.

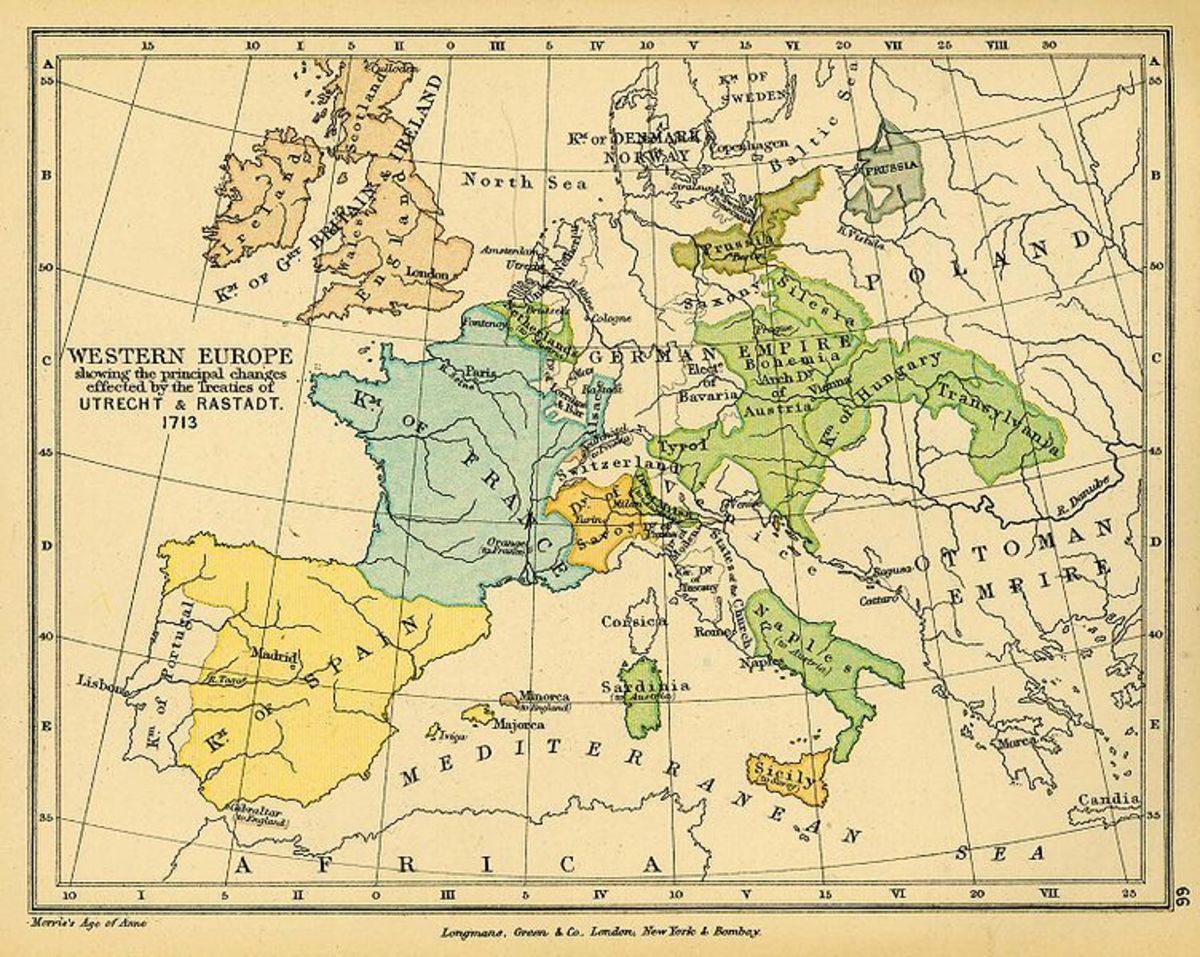

In ‘Part 2: How the Brain has Shaped our World’ he reviews, through another six chapters beginning with “Imitation and the Evolution of Culture”, the evolution of Western culture as manifested in art and philosophy in “The Ancient World” (Greece and Rome), “The Renaissance and the Reformation”, “The Enlightenment”, “Romanticism and the Industrial Revolution”, and finally “The Modern and Post-modern Worlds”. The take-home message is that cultural movements throughout history have see-sawed between right and left hemispheric modes of consciousness. Furthermore, each historical period can be seen as a developmental trajectory wherein the relatively unconstrained phenomenological perspective favored by the right hemisphere, which seeks understanding of the ‘other’ via imitation (as in the Renaissance imitation of classical Greek and Roman art), progressively gives way to the more rule-bound analytic perspective favored by the left hemisphere. Thus, for example, in ancient Greece poetry and tragedy gave way to philosophy; in the Middle Ages the Renaissance gave way to the Reformation; in the Enlightenment reason gave way to rationalization; in the nineteenth century Romanticism gave way to the Industrial Revolution. In each of these developments what began as a new (or renewed) way of looking at and relating to the world, of appreciating and empathetically embracing its intrinsic ambiguity and ‘otherness’ through art and metaphor, devolved into familiarized, literal interpretations much less tolerant of uncertainty and contradictions. Typically, the end of each period came with social collapse (e.g. the fall of Rome, or the French Revolution), arguably as a direct result of left hemisphere ascendancy.

A central idea developed in Part 2 is that during those periods of Western history in which artistic expression is generally considered to have ‘peaked’ (e.g the Renaissance), the cultural milieu favored the hemispheres working together in balance. According to McGilchrist this manifests aesthetically as a sort of ‘semi-transparency’, wherein the art works not merely to draw attention to itself, but more importantly to draw its audience into the ‘betweeness’ (what I would call intersubjectivity) that we each must negotiate in order to relate to (empathize with) the world. Initially and ultimately this is the job of the right hemisphere, which however needs the left hemisphere to get it done—to do the negotiating.

For it is the left hemisphere that, by linguistically manipulating the experience, interposes a working ‘space’ between subject and object, ‘self’ and ‘other’. But it only does so secondarily, by working with what it is given by the right. Furthermore, relating to the world requires that the left hemisphere give its rational ‘re-presentation’ of experience back to the right for reasoned action. In other words reason (Greek nous or noos)—which originates intuitively in the right hemisphere—informs rationality (logos), which arises linguistically in the left hemisphere—which then returns to again inform reason within the right. Thus (p.p. 330-331):

“The value of rationality, as well as whatever premises it may start from, has to be intuited: neither can be derived from rationality itself. All rationality can do is to provide internal consistency once the system is up and running. Deriving deeper premises only further postpones the ultimate question, and leads into an infinite regress; in the end one is back to an act of intuitive faith governed by reason (nous). Logos represents, as indeed the left hemisphere does, a closed system which cannot reach outside itself to whatever it is that exists apart from itself. According to Plato, nous (reason as opposed to rationality) is characterised by intuition, and according to Aristotle it is nous that grasps the first principles through induction. So the primacy of reason (right hemisphere) is due to the fact that rationality (left hemisphere) is founded on it. Once again the right hemisphere is prior to the left.

“Kant is commonly held to have reversed these priorities. At first sight this would appear to be the case, since for him Verstand (rationality) plays a constitutive role, and is therefore primary, while Vernunft (reason) plays a regulatory one, once Verstand has done its work. Rationality, according to this formulation, comes first, and reason then operates on what rationality yields, to decide how to use and interpret the products of rationality. However, I do not think that Kant’s formulation embodies a reversal as much as an extension. There was something missing from the earlier classical picture that reason is the ground of rationality, namely the necessity for rationality to return the fruits of its operations to reason again. Reason is indeed required to give the intuitive, inductive foundation to rationality, but rationality needs in turn to submit its workings to the judgement of reason at the end (Kant’s regulatory role). Thus it is not that A (reason) → B (rationality), but that A (reason) → B (rationality) → A (reason) again. This mirrors the process that I have suggested enables the hemispheres to work co-operatively: the right hemisphere delivers something to the left hemisphere, which the left hemisphere then unfolds and gives back to the right hemisphere in an enhanced form. The classical, pre-Kantian, position focussed on the first part of the process: A (reason) → B (rationality), thus reason is the ground for rationality. My reading of Kant is that it was his perception of the importance of the second part of this tripartite arrangement, namely that B (rationality) → A (reason), the products of rationality must be subject to reason, that led him to what is perceived as a reversal, though it is better seen as an extension of the original formulation.”

“Reason depends on seeing things in context, a right-hemispere faculty, whereas rationality is typically left-hemisphere in that it is context-independent, and exemplifies the interchangeability that results from abstraction and categorisation. Any purely rational sequence could in theory be abstracted from the context of an individual mind and ‘inserted’ in another mind as it stands; because it is rule-based, it could be taught in the narrow sense of that word, whereas reason cannot in this sense be taught, but has to grow out of each individual’s experience, and is incarnated in that person with all their feelings, beliefs, values, and judgements. Rationality can be an important part of reason, but only part. Reason is about holding sometimes incompatable elements in balance, a right-hemisphere capacity which had been highly prized among the humanist scholars of the Renaissance. Rationality imposes an ‘either/or’ on life which is far from reasonable.”

And this is why philosophy brings us to the doorstep of madness—as perhaps epitomized by that quintessential Enlightenment philosopher, Rene Descartes, whose dualistic proclamations about a disembodied mind (with its ‘all-seeing’ eye in the theater of thought) that gets trapped in a rather alien and altogether mechanical body sounds almost schizophrenic. The trap of philosophy—and of science unconstrained by humanity—is the trap of the left hemisphere thinking it knows best. And so the Enlightenment, the ripened fruit of Western philosophy, devolved into the madness of the French Revolution, which ironically enough resulted in the literal disembodiment of many a head. The other political product of the Enlightenment, the American Revolution did not ultimately fare much better, as the egalitarian ideals of its founding fathers devolved into (p. 346)

“the large-scale, rootless, mechanical force of capitalism, a left-hemisphere product of the Enlightenment. What de Toqueville presciently saw was that the lack of what I would see as right-hemispere values incorporated in the fabric of society would lead in time to a process in which we became, despite ourselves, subject to bureaucracy and servitude to the State: ‘It will be a society which tries to keep its citizens in “perpetual childhood”; it will seek to preserve their happiness, but it chooses to be the sole agent and only arbiter of that happiness.’ Society will, he says, develop a new kind of servitude which ‘covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate…it does not tyrannise but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupifies a people, till each nation is reduced to be nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which government is the shepard.’”

The Romantics at the turn of the 19th century strove to bring things back into balance with their art, which had a renewed depth and appreciation for nature. But the Industrial Revolution was already underway, and the danger it presented was already becoming apparent, as shown by Mary Shelley’s all-too-prescient novel Frankenstein. Mechanized industry, a product of the left hemisphere, greatly magnifies the latter’s power. And at the same time, it fosters the creation of an insular environment that gives the strong illusion of freedom from the natural world, which makes it seem that the superior attitude of the left hemisphere is warranted. As noted above, the result of all this is a positive feedback loop that engenders the runaway ascendency of the left hemisphere.

And this is what gave rise to modern madness (as manifested in myriad ways, for example in the impenetrability of so much modern art) and post-modernism. Post-modernism is often thought of as the antithesis of modernism, but in reality it is nothing more than what must naturally happen when modern philosophers go one step further to peer behind the curtain, only to find that there is nothing there—the entire edifice of modernism is but a ‘hall of mirrors’. We enter that hall when left hemisphere mentality becomes enamored of itself and conemptuous of that of the right, and as a result we become disconnected from reality. We need the right hemisphere—its way of perceiving, intuiting, empathizing, and indeed, of being—to stay grounded in the real world.

If you’ve read this far you no doubt get that I really enjoyed this book. While reading it I had the rare pleasure of having the pieces of a puzzle that I had collected over the years fall into place. McGilchrist, like any great thinker, ‘stands on the shoulders of giants’, whom he cites in an extensive list of references. The latter include Lakoff and Johnson, who have written of the embodiment of mind and the central importance of metaphor as a linguistic device for relating to the world. And on this particular point I think it is worth returning once more to briefly consider how McGilchrist’s thesis relates to that of Jaynes, who also discussed the importance of metaphor in the development of human consciousness.

As noted above, McGilchrist, while sympathetic to much of Jaynes’s theory, disagrees on fundamental issues such as the nature of schizophrenia and how the relationship between the hemispheres changed over the course of human history. It thus bears asking: can the two theories be reconciled?

I think they can. I tend to agree with McGilchrist that schizophrenia is most likely a modern malady rather than a throwback to a more primitive condition. But Jaynes did not claim that the ancients were schizophrenic, only that their experience of realistic hallucinations (interpreted as ‘gods’) was similar to that of modern schizophrenics. The key point, with which I think McGilchrist agrees, was that for the ancients these hallucinations originated as poetic directives in the right hemisphere that were received (literally ‘heard’) in the auditory center of the left. At that stage of human development the right hemisphere was clearly ‘in charge’, and this might be attributable to the left hemisphere having been relatively underdeveloped compared to today.

So what Jaynes refers to as a ‘breakdown’ might better be referred to as a ‘shift in the balance’ of the bicameral mind, as the left hemisphere came (via development, according to Jaynes, of metaphorical language) into ascendency, resulting in ‘silencing’ of the divine voices emanating from the right. We still have a bicameral mind—it’s just that the balance of power has shifted dramatically from one chamber to the other, from the right hemisphere to the left.

Of course, and unbalanced mind is not healthy, whether it be unbalanced toward the right hemisphere (as in the ancients who attended to the voices of hallucinated ‘gods’) or toward the left (as in modern times since the Enlightenment). Health entails balance. Unfortunately, balance—a ‘metastable’ state of poise between alternative ‘attractors’ or ‘wells of potential’—is by nature difficult to maintain indefinitely. Sooner or later events conspire to tip the balance one way or the other, inducing the development of one or another alternative ways of being.

And this brings me to the root reason I resonated so strongly with McGilchrist’s thesis. He argues that the left hemisphere re-presents explicitly what the right presents implicitly. This echoes my own conception of development (derived from Charles Sanders Peirce, via Stan Salthe and others) as being a trajectory of change that makes the implicit explicit, transforming that which is vague (or metaphorical) into that which is definite (or literal). As I discussed in an earlier hub, this is expressed in the specification hierarchy, which decomposes into the basic dichotomy {generic{specific}}, or alternatively (and perhaps better), {general{particular}}, {implicit{explicit}} or {vague{definite}}. This form be can mapped to {(Possible){(Actual)}}, or {(wave){(particle)}}, which develop over time by {(Initiation) → {(Positive Feedback)}} or {(Incipience) → {(Maintenance)}} (the parentheses are used to indicate a developmental process or condition inhering at each level of the binary hierarchy). So, McGilchrist’s thesis regarding the relationship between right and left hemispheres is essentially that they constitute a mental system wherein development of subjective experience is initiated by the right and culminated by the left.

And this then is why it makes sense that historically, in the evolutionary development of humanity, the balance shifted progressively from right hemisphere dominance (as experienced by the ancients) to left hemisphere dominance (as we experience): it is a natural developmental progression. By nature development has only two possible resolutions: metamorphosis (a trajectory of implicit → explicit → implicit) or extinction (implicit → explicit → extinct). Although both types of progression occur, the latter is more common, and perhaps in our case more likely. On the other hand, the ultimate resolution of development—either by metamorphosis into a new implicit (immature) trajectory (a system adopting a new way of being), or by extinction—is inherently unpredictable, and therein rests our hope for the future. Of course, this is not something that the left hemisphere finds easy to ‘grasp’.

McGilchrist’s thesis can also be related to that of neurobiologist Terrence Deacon, who argues that mind emerges from matter by way of asymmetric juxtapositioning of orthogonally opposed orthograde (spontaneously occurring) tendencies. The human brain, in its asymmetric bilateral anatomy, can be viewed as a developmental engine for accomplishing just that.

In the end, I do have one (relatively minor) criticism of The Master and his Emissary, and that is that there is a very real danger of ‘reading’ one’s prejudices into the divided brain model, by segregating what you like and dislike between hemispheres. Perhaps McGilchrist does this—the picture he paints of the left hemisphere is not very flattering, and it seems to be the vessel of all that he sees wrong with modern humanity. Moreover, the model is no doubt an oversimplification, as McGilchrist himself acknowledges, and as all models ultimately are. But this danger stems directly from the danger of taking models too literally (a proclivity of the left hemisphere), which can be avoided simply by granting metaphor the respect that it is due. Metaphorical interpretations, often disparaged as being ‘squishy’ or ‘unrealistic’ by modern Western culture, implicitly acknowledge that all of our thoughts and ideas are mere models. Literal interpretations—whether they be religious or scientific—lose site of this fundamental reality, and as a result, disconnect us from the world. When this happens insanity ensues.

And so McGilchrist concludes (p.p. 461-462):

“The divided nature of our reality has been a consistent observation since humanity has been sufficiently self-conscious to reflect on it.... When one puts that together with the fact that the brain is divided into two relatively independent chunks which just happen broadly to mirror the very dichotomies that are being pointed to—alienation versus engagement, abstraction versus incarnation, the categorical versus the unique, the general versus the particular, the part versus the whole, and so on—it seems like a metaphor that might have some literal truth. But if it turns out to be 'just' a metpahor, I will be content. I have a high regard for metaphor. It is how we come to understand the world.”