The National Anthem, a country doctor, and the War of 1812

He was a country doctor, gentleman farmer, miller, and patriarch of the small county seat of Upper Marlboro, Maryland. Now the former Revolutionary war physician, Dr. William Beanes, once again found himself facing his British adversaries. At around 2PM on that August 22nd afternoon in 1814, a British invasion force was moving north toward Washington following it's landing at Benedict, Md. At 65, the elderly Beanes was the only resident still in town and he soon found himself hosting British Major General Robert Ross for the evening. Ross thought Beanes was friendly and the surroundings pleasant, but he had bigger matters on his mind.

Ross's first objective, the American fleet under Commodore Barney, had just been scuttled by the Americans on the nearby Patuxent River. Now his Army sat only 16 miles from the Capital. With his fleet 30 miles away and lacking local intelligence on the whereabouts of American forces, Ross was harboring doubts about the operation. By morning of the 23rd, though, British Rear Admiral George Cockburn joined him with reinforcements and artillery, and persuaded him to move on Washington.

By 2pm the British were again moving, now west toward the Capital. They met, fought, and dispersed the American force at Bladensburg, then moved into Washington where they occupied the city, burning numerous buildings including the Capital and the President's house. By 1 A.M. on the 26th, they were on the move once more, retracing their earlier route back to Benedict and the fleet, again by way of Upper Marlboro.

As the Army marched, many stragglers and deserters fanned out into the local countryside, looting and pillaging the homes and farms that surrounded the route. After the main army passed Upper Marlboro, local landowner and former Maryland Governor Robert Bowie enlisted the aid of Dr. Beanes and several other locals to do something about the marauders. They soon bagged six or seven of the British stragglers and locked them in the county jail, with one managing to escape. The fugitive was able to report back to Ross's forces and by the early hours of August 28, Dr. Beanes, Bowie, and 2 house guests, all roughly roused from their beds, were in the custody of a party of British horsemen. They were returned to the fleet where all except Beanes were quickly exchanged for the jailed British soldiers. Beanes was thrown into the brig of the flagship Tonnant on orders from General Ross, who seemed to have taken on a personal dislike of his former host.

Dr. Beanes was well connected and his friends immediately enlisted the services of politically connected Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key to negotiate his freedom. Key went to President Madison to request permission to visit the British fleet under a flag of truce in order to seek Beanes' release. Madison agreed and arranged for Key to be accompanied by the American prisoner of war agent, John Skinner, who was well known and trusted by the British. There were still British wounded in Washington and an offer was made by Skinner to forward their personal letters to the British fleet under the same flag of truce.

Key traveled to Baltimore, met up with Skinner and boarded a sloop owned by Benjamin and John Ferguson that was to be the flag of truce vessel. They were underway by Monday, September 5th, sailing out of the Baltimore harbor, past star-shaped Ft. McHenry, down the Patapsco river and into the Chesapeake Bay. They met up with the British troop convoy and were escorted down the Bay toward the main fleet, the packet of letters from the wounded British troops being sent ahead by dispatch boat. Rather than being anchored off Tangier Island as expected, the main fleet was encountered on the 7th, already fully underway northward. Skinner and Key were transferred to the Tonnant to negotiate Beanes' release. General Ross, having already read the prisoner letters detailing their good treatment by the Americans, was moved to release Dr. Beanes. The matter was quickly concluded.

Unfortunately for Key, Skinner, and Dr. Beanes, there had been a sudden shift in British strategy by Admiral Cochrane. Instead of leaving the Chesapeake for New England, the British fleet was now moving to attack Baltimore. Having seen and heard too much, the Americans and their sloop would remain with the fleet until the operation was over.

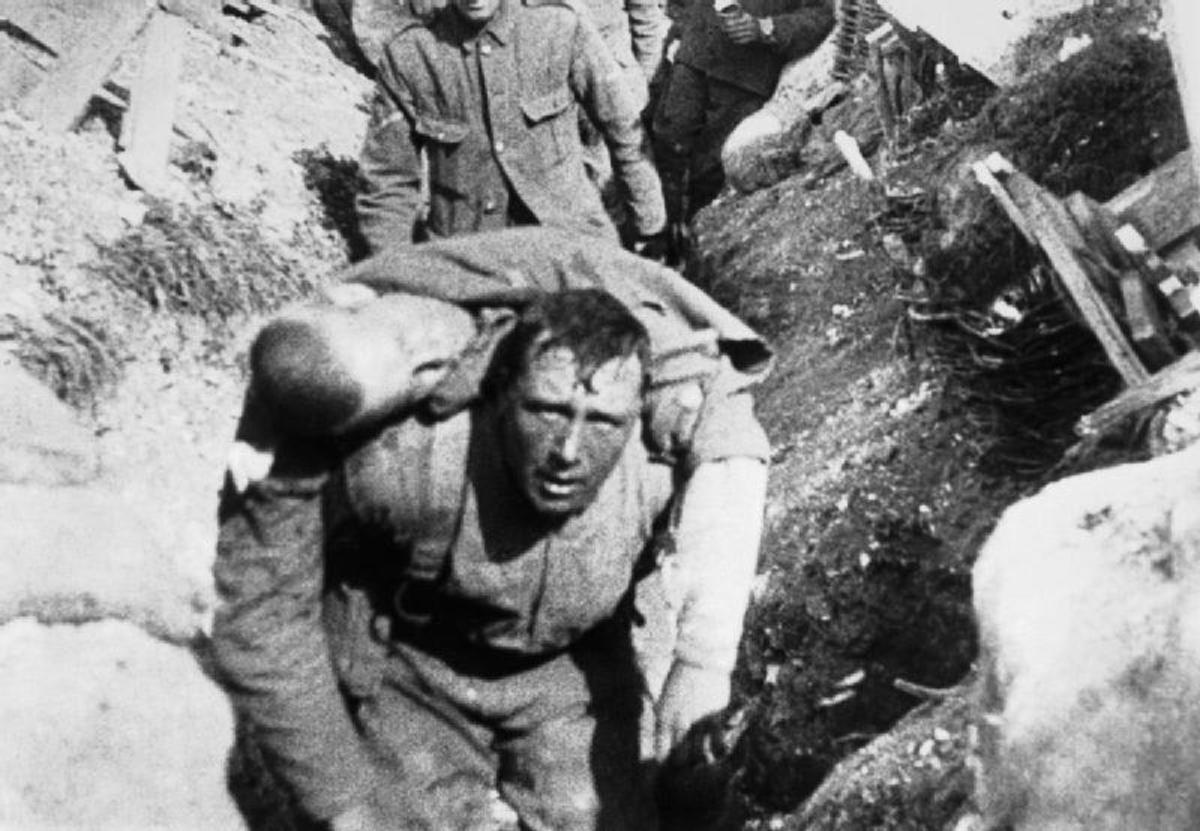

The fleet approached North Point, 12 miles below Baltimore on the 11th, and by 3AM on the 12th, British troops were disembarking. By 7AM they were moving toward Baltimore, anticipating a repeat of Washington. This time, the American troops, led now by Major General Sam Smith, were ready, and the defenses around the city had been well prepared to meet the enemy. The British advance proved costly as the regulars encountered the American militia. General Ross, leading the advance, was killed early in the afternoon, and by nightfall, the cost had risen to 300 British casualties. The following day the British troops made several probes of the strong American defensive positions, then returned to their camps. By 3AM on the 14th, they were on the march back to the transports.

Meanwhile, at dawn on the13th, the fleet opened its bombardment of Fort McHenry with mortars and rockets, a fierce barrage that was to continue for nearly 24 hours. From their sloop anchored with the British transports 8 miles below the fort, Key, Skinner, and Dr. Beanes watched the fuse arcs of thousands of 200 pound bombshells, Congreve rockets, and signal flares light up the stormy sky throughout the night as the fort was relentlessly pounded. Just before dawn, the display suddenly ended. Key anxiously scanned the horizon with his glass, and by first dawn, was able to glimpse the 40x32 foot American flag defiantly waving over the ramparts. On the back of a letter, Key, a poet at heart, began to write down the epic phrases that would become our national anthem, "The Star Spangled Banner".

The small town country doctor had indeed influenced the future of our great nation.