Incentives and Rewards in Schooling

“Julie and Johnny need ‘extra help,’ so I guess that’s why their pride cards get more punches.” No one has come out and explained this to her, but this is the reason she deduces from the available information. She knows she’s “been good,” but that her card is half full.

Half Full or Half Empty

Children whose cups (or cards if you will) are naturally half full often suffer this ethical dilemma. When my daughter was in first grade, she attended a school that had an elaborate, school-wide character points system. Doing your work, obeying the rules, and helping others to remember the rules all equated to a punch. The card was housed in each child’s classroom. Once the card was filled, the child was allowed to proudly walk his or her card to the office to choose a prize from the principal’s chest of treasures. Trinkets which were much like those found in a dentist’s or doctor’s prize chest.

While the desire to learn is intrinsic, the desire to work or do one’s best is not always so intrinsic. There are legitimate reasons for using a spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down, but our intentions can sometimes get away from us. Extrinsic motivational strategies, when done sparingly and with careful intention, can infuse fun into character building or content acquisition, but the choices of when to use extrinsic motivation need to be carefully evaluated and monitored. When not done well, it can send unintended messages to the children its attempting to foster.

In my daughter’s case, two things began to occur. The first was that the classroom teacher, a truly kind-hearted teacher, attempted to give her students ample opportunities for earning reward. The difficulty came in managing those ample opportunities.

Time Management

Because the cards were housed in the primary classroom, the students’ teacher was solely responsible for physically punching the cards (unless she had a parent or high school volunteer come in to help with the task). Naturally, it would be a huge disruption for the teacher to continually stop what she was doing in order to punch the cards, so the solution the school had come up with was to move the cards along pocket charts. When a punch was earned, the child could move his or her card forward. When it reached the end of the chart, the teacher would give it the number of punches earned and return it to its starting position. An especially good day (or an especially disruptive day where the teacher might find him or herself needing to rely more heavily upon the system) might result in the teacher’s falling behind in punching. The problem is complicated more so when it’s a school-wide system and students can earn punches from other staff within the school. When they return to their homeroom, they’re supposed to be able to move their cards forward for punches earned outside the primary classroom.

Any teacher in that position might be tempted to excuse him or herself from falling behind with the self-reassurance: “It’s not really about the punches; it’s about the behavior.” However, the children have been blocked from making that kind of leap by the nature of the system itself. They have been given a goal (in this case, a coveted prize from the chest) and given a means of achieving the goal. The goal is now their focus—not the behaviors being rewarded. They are now only the means to the end.

Rewarding Rule-Breakers and Punishing the Good

The second pitfall to this kind of a reward system is its tempting uses for differentiation. As a classroom teacher, I readily used differentiation. I hung a sign in my room for student and parent understanding: In this classroom FAIR is not everyone getting the SAME, but rather what he or she needs to learn BEST. "Why doesn’t Johnny have the same homework I do?"

"Because I designed your homework for you—and Johnny’s for him. I want each of you to work on what you most need practice in."

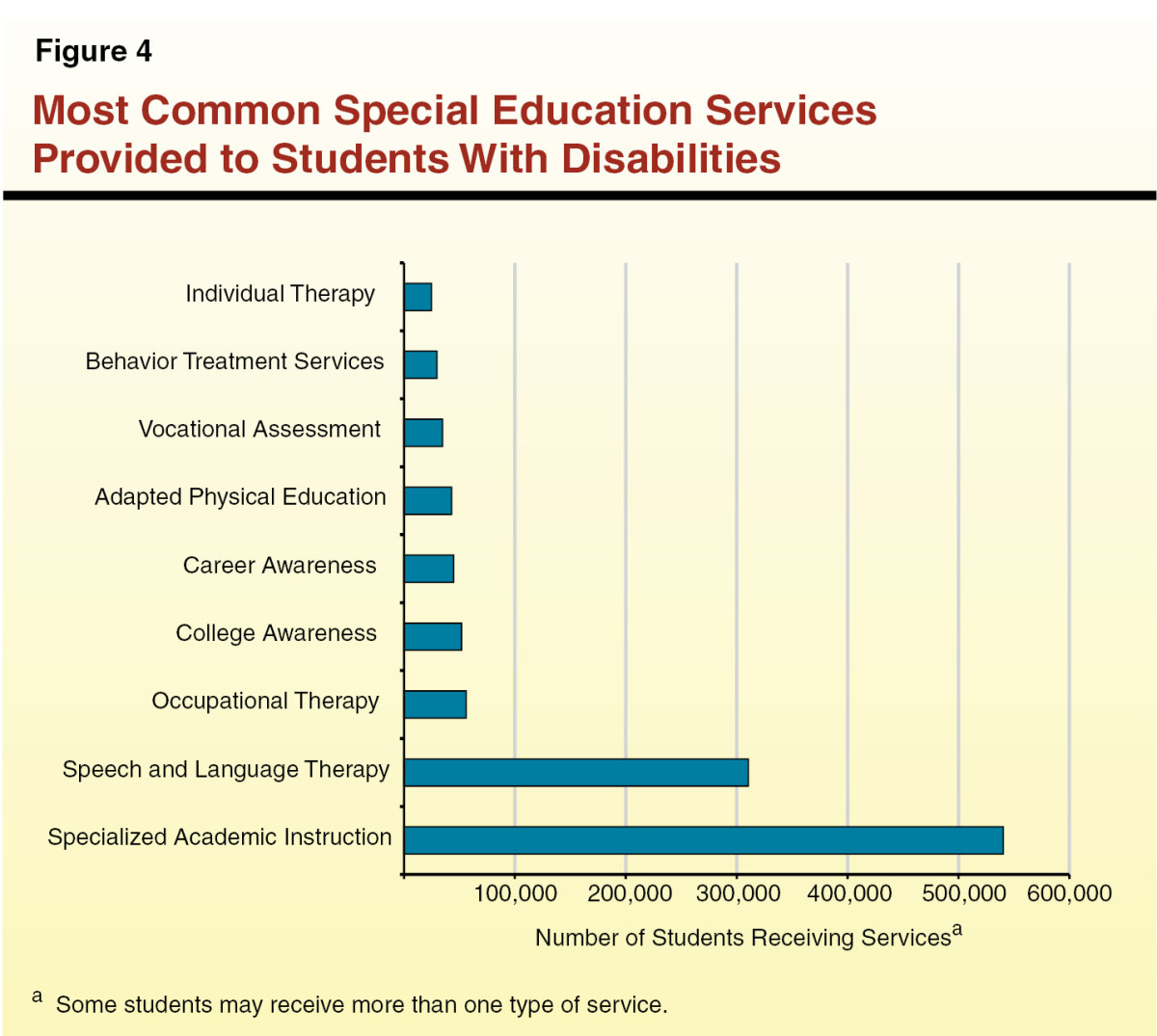

The idea of differentiation is to help kids understand the concept of equality—or what educators might call “inclusive excellence.” Every classroom is made up of twenty or so different students, each with his or her own strengths and weaknesses, skills and difficulties. Extrinsic motivators should never be used in combination with differentiation because it actually robs inclusive excellence of its moral basis. If the point of differentiation is to be attuned to each student on an individual level, the teacher necessarily has to create a culture of understanding around her methods so students come to understand that one person isn’t getting more or less (harder or easier) work—just different work. "You’ve mastered this skill, but you need work in X whereas Julie has mastered X but needs work in Y."

If you throw extrinsic motivation into the mix, the outcome is a de-motivation for those students who master their given tasks more easily or quickly than do the Julies or Johnnies. Now, instead of seeing Julie and Johnny as different but equal, the children who masters their skills with more ease come to see Julie and Johnny as “special needs.” Not different needs—but special. It is unreasonable of us as adults to expect any child to have a carrot dangled in front of his or her face and then watch us hold it just out of reach and hand it over to someone who, in the child’s young mind, doesn’t seem to be earning the reward. This is especially true (and especially dangerous) if Julie or Johnny has behavioral, as opposed to learning, needs. My daughter knew that she was more well-behaved than Johnny was—Johnny didn’t listen to the teacher; he talked back; he got into conflict with whoever sat next to him, etc. However, his character pride card was always being moved for the slightest good example of behavior while hers was stuck in position three needing to be punched, yet she was always listening, never talking back, never getting into conflict . . . .What child in that scenario wouldn't come to be less tolerant of Johnny's behavior rather than more empathetic toward it?

Brief Bio:

Jenn Gutiérrez holds an M.F.A in English and Writing. Previous work has appeared in journals such as The Texas Review, The Writer’s Journal, The Acentos Review, Antique Children, and Verdad Magazine. Her 2005 debut collection of poems titled Weightless is available through most online book outlets. She currently teaches composition at Pikes Peak Community College and is working on a doctoral degree in Curriculum & Instruction at the University of Denver.