Influence of Seventeenth-Century Indian Politics on Painting

Introduction

Before the advent of the Mughal invasion, the sons of kings (Rajputs) who were Hindus, established kingdoms in western parts of India, later dubbed ‘the place of kings’ or Rajasthan. The kings initially resisted the domination of the Mughals to preserve the classical Hindu culture. However, they inevitably adopted many of the invaders’ fashions and customs. One of the customs and trends, which was also politically promoted, is the delicate and naturalistic finish of Mughal painting. Artists from both sides mixed artistic styles in creating paintings of various categories such as portraits, historical paintings, and architecture. Hence, the urge to know the extent of the role played by politics in revolutionizing painting in Rajasthan during the seventeenth century informs the writing of this essay. Owing to the emergence of Mughal-Rajput painting after Mughals invaded Rajasthan, it is true that political events are both, directly and indirectly responsible for the development of paintings during the seventeenth century in Rajasthan.

Influence of Mughal Rule on Paintings

Created by the invasion of Rajasthan by Mughal was the Mughal-Rajput painting relationship. During the period, political activities and personalities of the male leaders of Rajput courts solely determined painting developments.[1] Local schools in Central India and Rajasthan incorporated elements of the Mughal painting style during the seventeenth century in varying degrees. Linked both politically and economically with the Mughal rule were the courts of Bikaner, Jaipur, Kishangarh, and Bundi, which participated in combining Mughal and Rajasthani features with assurance and ease. However, some of the Mewar painters of the era whose royal patrons failed to subjugate to the Mughal leadership did not wholly adopt the Mughal style of painting.

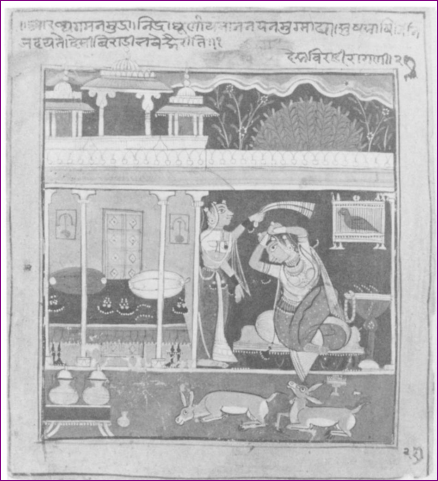

Appendix one and two are examples of Mewar’s early seventeenth-century paintings. They have identical features that render their identification easier such as their angular forms, bright colors, and two-dimensional layout. Both paintings represent the earliest set of pieces painted in the Mewar seventeenth-century painting. The painters used postures and figures to communicate the central meaning of the paintings that mainly revolved around the illustration of literary and religious texts.[2] Some of the traits like less bold and dramatic eyes, less emphatic gestures, and softer figures exhibited by the paintings relate to Mughal tastes. Hence, they are evidence of the Mughal-Rajput relationship.

Akbar, the third Mughal Empire of India launched the largest painting workshop in the land in a bid to promote art. Seventeenth-century paintings during the Akbar period reflect the political and cultural environment in which they were commissioned and produced. Some of the creation of this atelier included portraits of powerful religious, cultural, and political leaders across north India.[3] The portraits influenced the very regime that politically enhanced their development by shaping Mughal military and political policies. According to Akbar’s belief, the images provided significant information concerning people’s governing abilities, personalities, and loyalties. An exploitation of such traits could lead to political profit.

The Mughal’s dynasty, atelier, produced the most conspicuous paintings in terms of color, style, and matter in the seventeenth century. According to some scholars, such pronounced elements were due to the political support by the empire and cultural association of the Bika Rathores.[4] As a result, the Mughal influence resulted in informed choices by the Bikaner painters evidenced in their mastery of both Rajasthani and Mughal painting styles. Besides, the art of Shah Jahan’s court heavily influenced the Bikaner painting atelier during Karan Singh’s regime (1632-1669). Several paintings blended both the Mughal and Rajasthani idioms in a single piece while one of the styles dominated in some of the artworks. Marga or Rajasthani paintings dominated in courtly, religious, and literary subjects whereas Mughal stood out in historical paintings and portraits. Similar to the influence of Shah Jahan’s court art was the prolonged presence of the Rajasthani nobles in the Deccan, initially as warriors and later as governors during the late seventeenth-century politically impacted on painting. Their association and power made the immigration of Deccani artists like Bikaner and Kota in Rajasthan kingdoms possible, as artists accompanied them during their visits.

[1] Kossak, Steven M. 2013. Indian court painting, 16th-19th century. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art). 17-18

[2] Ibid. 18.

[3] Topsfield, Andrew. 2014. In the realm of gods and kings. (Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd). 228.

[4] BelliBose, Melia. 2015. Royal umbrellas of stone: memory, politics, and public identity in Rajput funerary art. (Leiden: Brill). 217.

Representation of Architecture in Paintings as Influenced by Politics

Before Mughals dominance over Rajasthan, Western Indian paintings gave little concern to architectural representation. The rulers after invasion demanded court painters to include paintings showing architectural surroundings in their work. For instance, architectural paintings created explicitly with the aim of amusing the king had illustrations of specific incidents that take place around the palace or paintings capturing a festive celebration.[1] In the long-run, artists developed affection to integrate architecture in paintings. Ragamala series of paintings serve as an example of artwork with architectural painting.

[1] Topsfield, Andrew. 2014. In the realm of gods and kings. (Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd). 228.

Conclusion

The Rajasthani painting of the seventeenth-century was an assimilation of a politically compelled artistic influence as well as the influences offered by traditions. As a result, a new mode of painting with compositions and themes that portrayed the lives of the people emerged. In essence, the divine favor of the elderly, the passions of common youths, and the transgressions of a simple village woman found a place in the artwork. The new painting mode was not limited to the geographical areas of Rajasthan; the modes also spread to Uttar and central India. An increased artistic pursuit during the era also encouraged the development of more sub-schools.

Bibliography

BelliBose, Melia. 2015. Royal umbrellas of stone: memory, politics, and public identity in Rajput funerary art. Leiden: Brill.

Kossak, Steven M. 2013. Indian court painting, 16th-19th century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Topsfield, Andrew. 2014. In the realm of gods and kings. Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd.

Appendices