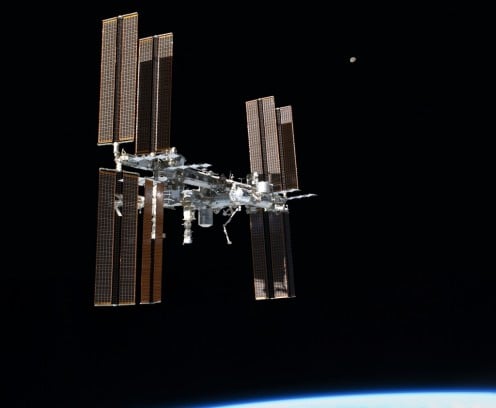

Invaders Are Eating the International Space Station (ISS)

Hungry Bugs

The International Space Station, parts of which have been orbiting the Earth since 1998, is being eaten by microbes that have stowed away on equipment and inside human crews. When the first crew members arrived in 2000, a stew of hardy microbes awaited their arrival-- and greeted the new microbes the humans brought with them.

The longer they are in the station, the more likely they are to evolve and become aggressive. They've already gone through the “selection” of cleansing on Earth and are exposed for long periods of time to cosmic radiation. The worst have eaten-- or corroded-- holes in metal panel covers, chewed through seals and wiring insulation, leaving bare leads-- even glass is being eroded by the tiny invaders.

MIR

“We had these problems on the old MIR space station, now we have them on the ISS. The micro flora is attacking the station. These organisms corrode metals and polymers and can cause equipment to fail,” said Anatoly Grigoryev, the vice-president of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Ultimately, MIR failed because of age and damage caused by microbes. The ISS is funded for operation until 2020 and could operate until 2028. The contamination gets worse as it ages.

They're Everywhere

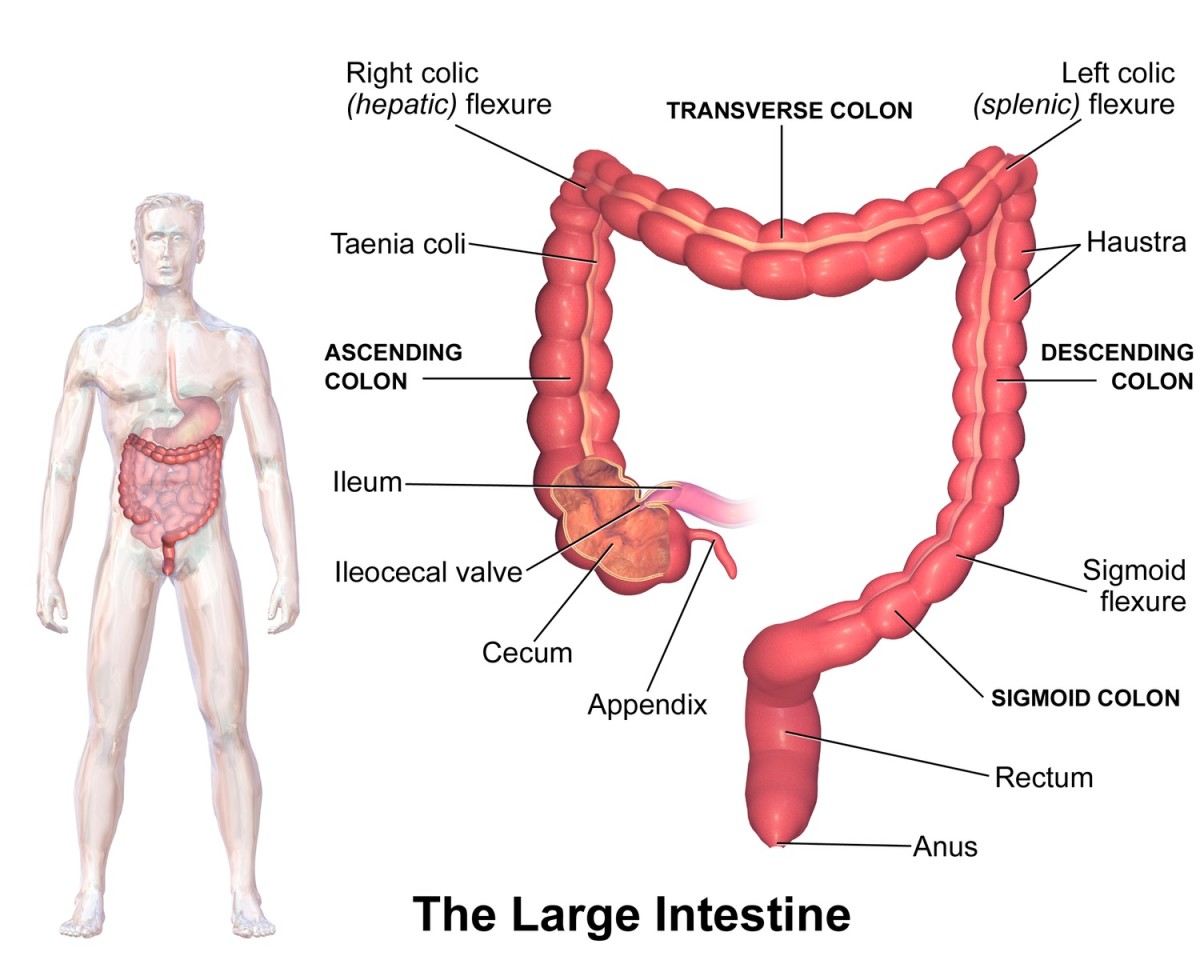

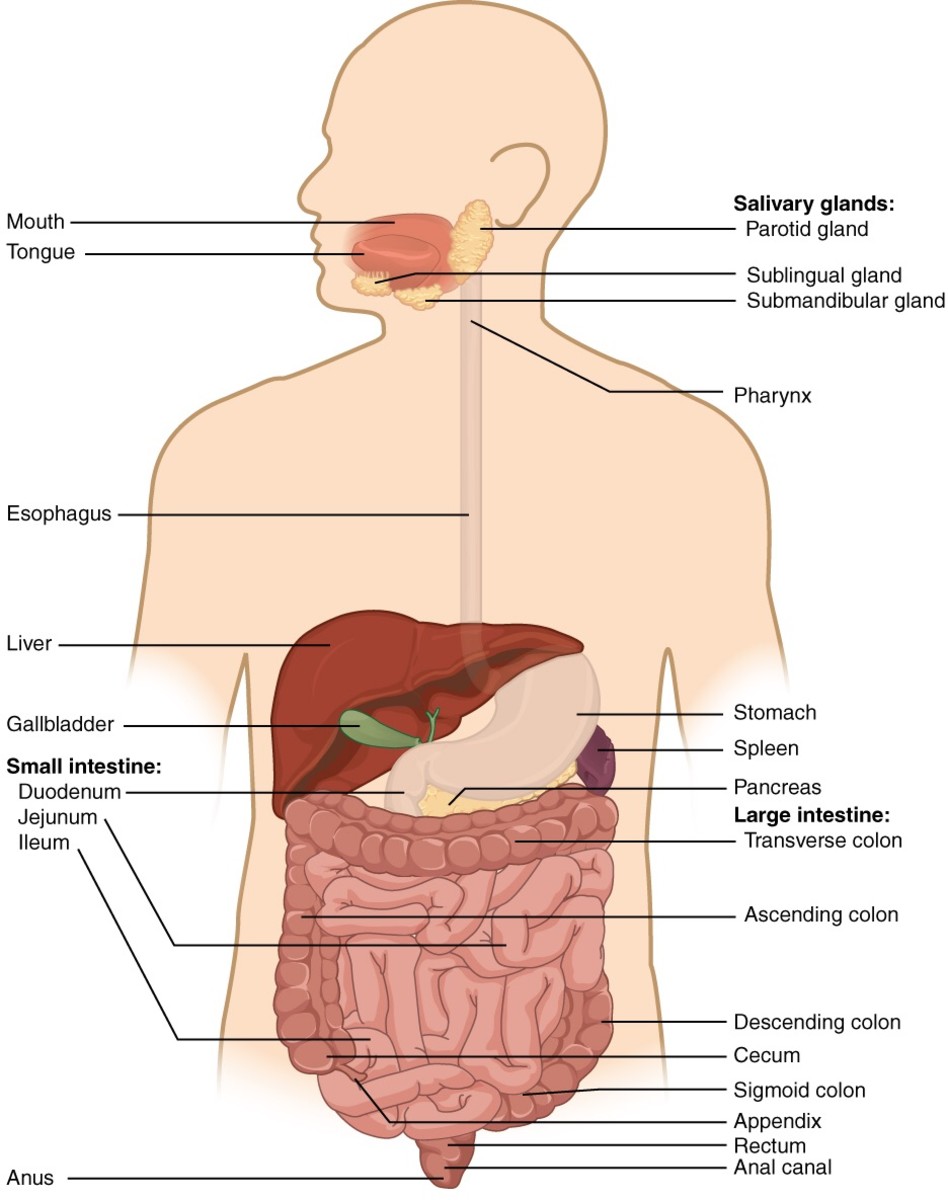

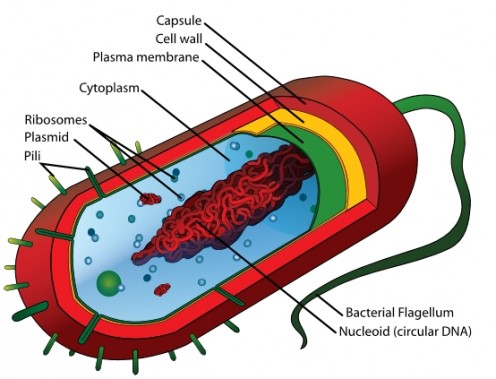

Microbes-- bacteria, fungi and viruses-- are, of course, everywhere, from the deepest, hottest sulfur vents miles below the ocean's surface to, now, outer space. Some microbes kill us, some keep us alive, but most are harmless. Without the beneficial microbes, we couldn't digest our food, produce vitamins and would be exposed to harmful bacteria if the good ones didn't crowd them out. We can't get away from microbes.

It's not like space station components are slapped together in a garage by greasy mechanics who don't wash their hands after defecating. Strict procedures are followed in quarantined areas and equipment is coated with anti-microbial chemicals to prevent microbes from hitching a ride on equipment, or, more correctly, to reduce the number of hitchhikers, and each crew member's health is strictly monitored. Still, nobody expects to achieve 100% sterility.

In the meantime, specially treated tissues are used by the crew to swab the surfaces in the ISS modules to keep the contamination under control. Unfortunately, there are many hard-to-reach places where wiping down isn't possible. Plans are in the works to send up a powerful anti-bacterial UV lamp soon; also, a special extinguisher designed for use behind the panel covers is undergoing tests.

We Don't Need No Stinkin' Space Ship

Experiments have shown just how hardy microbes are. In one test, small chunks of limestone from the cliffs of Beer, a small English village on the south coast, were collected and sent up to the station. The fragments, containing bacteria inside as well as on the surface, were placed outside the space station. The bacteria were constantly exposed to the vacuum of space, harsh ultraviolet light, radiation and extreme temperature fluctuations. After more than 550 days in space, many were still alive. Their progeny are thriving at the Open University in Milton Keynes.

What About Diseases?

Then there's the question of the effect mutated microbes might have on humans themselves. “Uncontrolled multiplication of bacteria can cause infectious diseases among the crew,” said Grigoryev. Nor is it clear what might happen when these microbes ride back to the surface of the Earth in their human hosts or returning equipment.

This is not to say the ISS is doomed or that humanity will be wiped out, but the microbe problem is not something that scientists are ignoring or taking lightly. In space, nothing can be taken lightly.