- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Marine Biology»

- Marine Life

International Court Harpoons Japanese Whaling

Following months of legal hearings regarding Japan's whaling program, The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague has finally ruled in Australia's favor by banning Japanese whaling boats from operating in the Antarctic.

The case was first brought to the ICJ in May 2010 by the Australian government, then led by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, seeking an order from the United Nations-backed court to end Japan's whale hunt. Japan's government had defended its whaling program by claiming that it was in the name of scientific research, though Australian officials argued that this was just a guise to carry out commercial whaling.

Hearings began in June 2013, where Australia argued that Japan's research program had killed more than 10,000 whales; had no relevance to marine conservation; and was a clear violation to international law. Japan's counter argument claimed that there were cultural reasons behind their whale program and that research findings were providing information on whale stocks, with the goal of re-examining the ban on commercial whaling in the future.

On March 31, presiding ICJ Judge Peter Tomka said the court had come to its decision with 12 out of 16 votes ordering Japan to end its whaling activities in the antarctic and withdraw all scientific permits.

"In light of the fact the JARPA II (Japan's whale research program in Antarctica) has been going on since 2005, and has involved the killing of about 3,600 minke whales, the scientific output to date appears limited," Judge Tomka said. "Japan shall revoke any existent authorisation, permit or licence granted in relation to JARPA II and refrain from granting any further permits in pursuance to the program."

Japan's government has stated that it "regrets and is deeply disappointed by the decision" but they will abide to the court's decision as "a state that respects the rule of law, the order of international law and as a responsible member of the global community".

However anti-whaling group, Sea Shepherd, have reported that Japan is planning to return to whaling in Antarctica with a newly designed research program in 2015-2016.

This hub explores the history of the current whaling controversy, with a specific focus on Japan, but also giving some attention to other whaling countries.

Whaling in International Law

By 1925 the League of Nations recognized that whaling stocks were exhausted and that due to the migratory nature of whales there was need for an international effort to regulate whaling activities. In 1930 the Bureau of International Whaling Statistics was set up in order to keep track of catches. In 1931 the Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was signed by 22 members, but excluded the involvement of some of the leading whaling nations, like Germany and Japan.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling that was signed into action on December 2 1946 in Washington. Its purpose was to avoid over-exploitation and depletion of whaling stocks. Originally there were fifteen signatories for the treaty: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, South Africa, The Soviet Union, The United Kingdom and The United States. Today the committee has grown to 88 members states.

One of the IWC's first achievements was the introduction of a quota system known as the blue whale unit. A unit was based on the relative oil yield of each individual whale species with one blue whale unit being equal to 2 fin whales, 2.5 humpback whales an 6 sei whales. The program was ineffective in preventing the exploitation of whaling stocks and the quota system was discontinued in 1972.

Moratorium

According to Greenpeace due to over-exploitation of whaling stocks by 1970, the total number of blue whales fell to less than 6,000, the quantity of humpbacks followed a similar downturn while the amount of Pacific gray, sei and sperm whales had been halved.

In 1972, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) passed a resolution to institute a ten-year moratorium on commercial whaling, with 52 members in favor and zero opposed. There were also 12 countries that abstained, including Japan who stated that though they were somewhat in favor of a moratorium, it was a decision that should be left to the IWC on the basis of all available scientific information.

Following the UNHCE resolution, there was much discussion among IWC member to enforce something similar and many attempts to achieve this objective. However these proposals never gained enough support from IWC members.

In 1982 the Commission was able to introduce a pause to commercial whaling declaring that "catch limits for the killing for commercial purposes of whales from all stocks for the 1986 coastal and the 1985/86 pelagic seasons and thereafter shall be zero".

Whaling Nations

Though this moratorium is still in place today, at least 47,677 fin, humpback, sei, minke, sperm, gray, bryde's, and bowhead whales were killed by IWC members from 1985-2012 for aboriginal subsistence, scientific research and commercial endeavors. IWC members that have hunted whales since the worldwide ban include: Norway, Japan, Iceland, Denmark (Greenland), South Korea, Russia, USA (Alaska) and St Vincent and the Grenadines.

South Korea has not officially practiced whaling since 1986, though whale products are legally sold in and consumed in the country if whales are inadvertently or accidentally caught by fisherman. Greenpeace says that Korea and Japan have the highest levels of by-catch anywhere in the world, with an average of 80 whales being caught in South Korea every year. Being responsible for 33% of whale by-product worldwide has allowed for a whale meat market to thrive in South Korea.

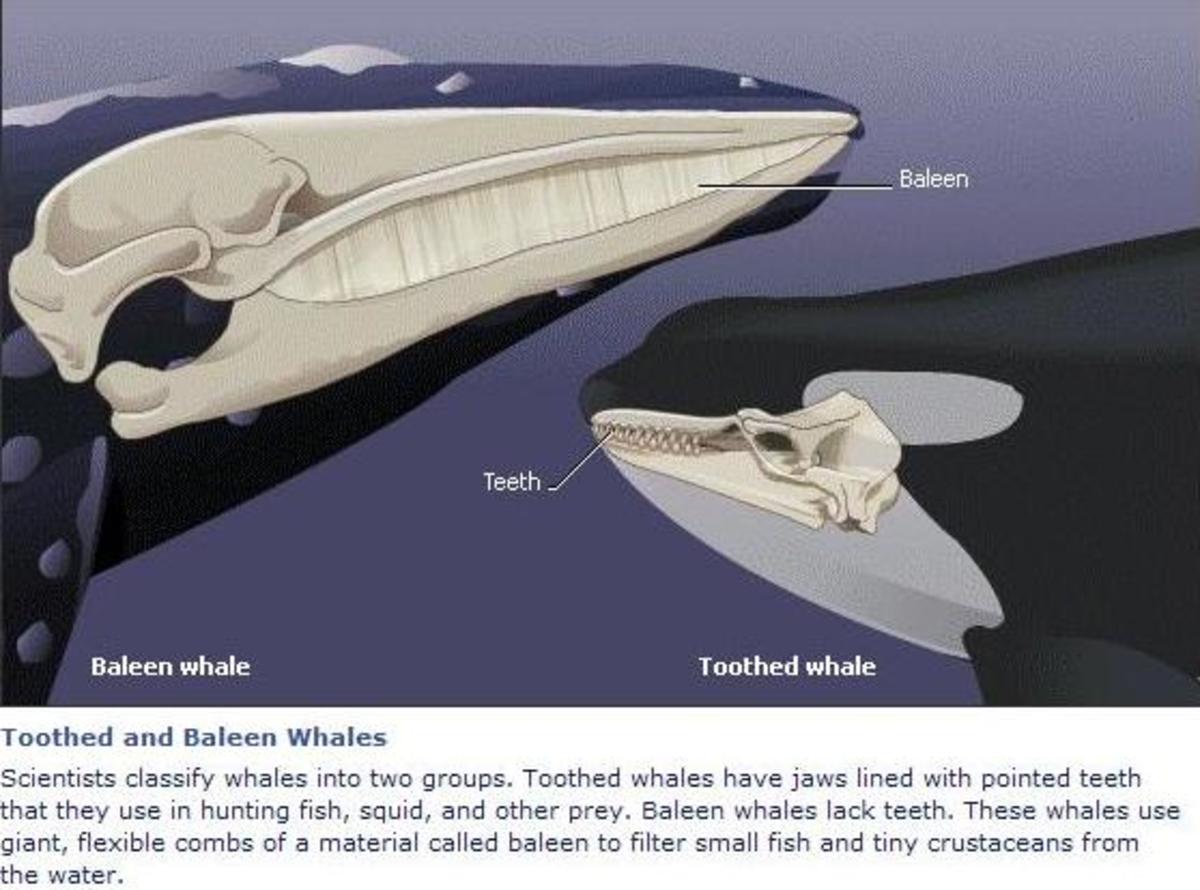

Whaling by non-members of the IWC include Canada, Indonesia and the Faroe Islands (an archipelago and autonomous region of Denmark). Canada, whose Inuit population hunts beluga, bowhead, narwhal and pilot whales, had become a member of the IWC in 1949, but let in 1982 due to a disagreement on the moratorium. Indonesia is known to hunt around 15-20 whales a year, most often sperm and toothed whales. The Faroe Islands have kept records of catch limits since 1584, with an annual average catch of 800 whales, with large fluctuations on a yearly basis, e.g. annual catches ranged from 1,572 in 1992 to zero in 2008. On average they capture around 1% of the estimated pilot whale stock.

Japan is the only whaling country that has a program which operates outside of its own territorial and economic boundaries, extending to the Antarctic and North Pacific Oceans.

Subsistence

Despite the worldwide ban on commercial whaling IWC allows whaling for aboriginal subsistence, setting permits for this practice. Since the whaling moratorium came into effect in the 1985/1986 season, at least 9,393 whales have been killed under the aboriginal subsistence clause with Denmark responsible for 48% of this number, followed by the USA, Russia and St. Vincent & the Grenadines.

In 2002/2003, as well as in previous years, Japan requested that the IWC grant an annual catch quota of 50 minke whales for aboriginal subsistence of the coastal communities, where whaling was fairly ingrained in their culture, economy and tradition for centuries. Japan failed to gain the necessary support from IWC members, so their request was not adopted.

Special Permits

The IWC also allows for "special permits" to be issued for "‘essential’ and ‘critical research’. The permits are not regulated by the IWC, but instead each nation sets its own quota. Since the 1985/1986 moratorium, 15,563 whales have been killed under these scientific permits, by Japan, Iceland and Norway, though South Korea had also killed 69 Minke whales in 1986. The majority of whales caught under special permits have been Minke Whales (13,509).

In Japan the Institute of Cetacean Research, which was established in the 1990s, issues these scientific permits, though many environmental groups have accused the organisation of merely permitting commercial whaling under the cover of scientific research. According to the IWC, Japan is responsible for nearly 95% of the total number of whales killed for scientific purposes. Though the whales are officially caught for research, the animals' meat find its way to the marketplace for public consumption.

Commercial Whaling

From 1985 - 2012 the number of whales killed for commercial reason in objection or reservation to the IWC moratorium was as high as 22,721. Norway makes up nearly 47% of this number followed by Iceland, Japan as well as the former USSR.

Norway, Iceland and Russia have either raised an objection or reservation (where countries remain a member to a treaty without being committed to any binding legal obligations) to the global moratorium, and therefore are not bound by it. However these countries are still required to submit all information on catches to the IWC.

The moratorium is binding on all other IWC members. This includes Japan, who despite withdrawing their initial objection to the ban in 1986 still went on to hunt and capture more than 5,500 Sperm, Bryde's and Minke whales commercially before finally abandoning commercial whaling after the 1987/88 Antarctic Season.

Russia has also objected to the worldwide ban, though they have not practiced commercial whaling since the 1987 Antarctic Season.

Norway and Iceland carry out commercial whaling within their Exclusive Economic Zones, mainly capturing North Atlantic common minke whales, though Iceland also hunts fin whales.

International Trade of Whale Products

Norway, Japan and Iceland are members The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 1973) but raised reservations on the prohibition to trade whale products. These countries are therefore legally allowed to trade whale products among themselves and other non-member countries to the CITES treaty. Iceland in particular has been singled for trading vast quantities of whale meat to Belarus and Latvia. Japan has alsobeen accused of secretly selling whale meat to South Korea and The United States, which would constitute a violation of the CITES treaty.

Lifting the Ban

Throughout the years there have been many arguments made in favor of lifting the global ban, and several attempts have been made to achieve it. Environmental Groups have accused Japan of trying to end the moratorium since the early 1990s by "vote consolidation operations", which involves recruiting members into the IWC (around 23 states by 2007) that would vote is favor for commercial whaling .e.g. St Lucia; St Vincent and the Grenadines; Grenada; Dominica; Antigua; Barbuda; and St Kitts and Nevis.

A few of the arguments in favor for lifting the ban claim that:

- The IWC Scientific Committee and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have estimated that the populations of many species of whale have recovered significantly by 1990 and that their numbers are sufficiently abundant to resume whaling at sustainable levels.

- The moratorium is unnecessary as major whaling nations are current members of the IWC, and this international body can adequately regulate whaling activities and ensure that stocks do not deplete.

- Though proposals to remove the global ban have been voted down each year by a majority of anti-whaling nations, the number of pro-whaling states continues to grow, ensuring that the moratorium will inevitably be overturned at an upcoming Annual Meeting,

Most recently and significantly in 2010 a proposal was brought before an IWC conference in Morocco to introduce a quota system for Japan, Norway and Iceland. The proposal would have permitted Japan to hunt commercially 400 minke whales for five years, and then 200 minke whales for the following five years. This would have been a significant decrease from its current annual yield of 850 minke and 50 fin and humpback whales a year.

The proposal for a quota system was not implemented,due to not receiving the required number of votes in favor. Australia, which was staunchly opposed to the proposal, described it as an attempt for "legitimizing commercial whaling, with concessions to whaling nations compromising the long-term goals to end whaling".

What Whales are Used For

Whale products can be broken down into a number of categories with various uses. Human applications for whale products include whale oil which has been used in cooking, crayons, detergent, dynamite, ice cream, lamp oil, linoleum, lipstick, lubricant, margarine, paint, polish, shampoo and soap.

In a single year 3 million barrels of oil could be produced from killing 29,400 blue whales. While there were many alternative sources of fuel for lamps and indoor lighting, in the 19th century the use of whale oil began to diminish in favor of kerosene derived from crude oil and vegetable oil.

The special filter known as a baleen, a comb-like structure that is attached to the creature's jaw allowing it to filter its food from the sea water, has also been used in a number of products, such as brushes, corsets, fishing lines and fans. Additionally whale tissues have been used in fertilizers, photographic film, jello, surgical thread, tennis racquets, shoes and sweets. The actual whale meat is known for its inclusion in the diets of humans, dogs and other animal feed.

Consumption of Whale in Japan

History

Despite Japan's current reputation as one of the world's leading whaling nations, prior to 1945 the country was a fairly small-time player in the whaling scene. Japan commenced whaling in the 12th century, utilizing hand thrown harpoons (a method known as tukitori-ho) as they mainly stuck around the coast with a minor whaling presence on the high seas. Japan generally practiced "passive whaling", taking whales that were either dead or injured. In the 16th century more active hunting programs were launched and in 1675 the country started using the net method (amitori-ho), contributing to a rapid expansion of whaling.

Whale meat was used in Japanese society as a form or payment. Several Shinto and Buddhist ceremonies and rites were also based on whaling activities. As a sign of respect to the killed whales there is reportedly a whale graveyard located in the Koganji Buddhist Temple in Nagato City and a service is held once a year in the temple to pray for their souls of the whales.

In 1934 Japan expanded its whaling efforts to Antarctica and harvested the whale meat to keep its citizens fed during and after World War II, with Japan's remaining agriculture and industry were insufficient to feed its population in the post-war period. With major concern on how the country would sustain its population, the U.S encouraged Japan to avoid starvation by increasing its whaling operations. By 1947 whale meat made up nearly half of all animal protein consumed in the country.

The 1954 School Lunch Act promoted the inclusion of whale meat in school lunches across the country, the first time that its consumption became nationwide. While this dietary inclusion disappeared from schools after the moratorium on commercial whaling in the 1980s, in 2005 whale meat began making a comeback at public elementary and junior high schools nationwide. In a 2010 poll, around 5,355 out of 29,600 (or 18%) schools stated that they had served whale in their lunches at least once in fiscal 2009 through March 2010.

Japan's Defense for Its Whaling Programs

In the face of criticism worldwide Japan steadfast and unwavering defense for its whaling programs is based on several beliefs, which include:

- Japan's tradition of eating whale meat for thousands of years, which has led many Japanese to believe that they have a somewhat distinct and unique whale eating culture.

- Whales are usually considered a type of fish in Japan, rather than a mammal, therefore resulting in Japanese holding a lesser appreciation appreciation or belief in whales' right than other countries.

- Japanese resentment to what is perceived as Western interference in their indigenous practices, including that foreign criticism is a form of racism with an intolerance to cuisine from non-white societies.

- Some whale species are abundant and actually risk destroying the marine ecosystem by depleting fish stocks. Therefore reducing their numbers helps the ecosystem.

- Whaling is no more barbaric than the Western countries butchering of livestock for consumption, while wasting substantial amounts of the animal meat.

- In Japan's small coastal whaling communities many whalers descend from generations of whalers, who are expected to continue their family occupational tradition as a sign of respect to their ancestors. A failure to achieve this expectation is considered a disgrace and a source of deep shame

Public Opinion

A number of polls have been taken over the years to get an idea of Japanese sentiment towards whaling. Though all of these questionnaires have identified differing trends and opinions on Japanese whaling, they clearly indicate that public support for whale meat is hardly unanimous.

- In a 1992 questionnaire involving across six countries, a difference in opinion was identified between the populations of whaling and non-whaling nations. In Australia, which prides itself in being "one of strongest anti-whaling countries", 64% of people said that they could not imagine killing anything as smart as whales, compared to 21% in Japan. Around 21% of Australians said that they had no problem with whaling as long as its properly regulated; while 64% of Japanese held the same view.

- A 2006 Gallup Poll found that 95 percent of 1,047 respondents said that they rarely ate whale meat, had not eaten whale meat in a long time or not eaten it at all. The poll found 90% of those who supported commercial whaling claimed that it was a traditional aspect of Japanese culture. Males aged 40 to 59 are the most likely to enjoy a platter of whale meat, possibly seeing it as a sentimental favorite from their childhood in the years following World War II. In comparison most of the younger age groups had never eaten whale meat, were against commercial whaling and disagreed that the practice was an important aspect of Japanese culture.

- Another 2008 Greenpeace questionnaire found that 31 percent of respondents were in favor of commercial whaling; 25 percent were against it; and 44 neither supported or rejected the practice. In contrast in 2006, 35 percent in favor; 26 percent were against; and 39 percent had no opinion.

- In another 2008 poll by newspaper Asahi Shimbun 56% percent of respondents supported eating whale meat while just 26% opposed it.

- A 2009 review conducted by the University of Tasmania and involving Japanese youth aged 15 to 26, found that males were accepting of pro-whaling rhetoric and consumption of whale meat and this support grew as they got older. Female respondents were generally against pro-whaling rhetoric, with younger women having a higher degree of disapproval than older females. However older women had a greater opposition to consumption of whale meat.

- A poll conducted by Nippon Research in October 2012 found that 54.7% of Japanese citizens were indifferent to whaling; 27% said that they support whaling, though only 11% strongly support it; 89% said that they hadn't bought any whale meat in the last 12 months; 85 percent expressed opposition to the use of billions of taxpayer yen to build a new factory ship (currently Japan only has one research whaler factory ship, the MV Nisshin Maru).

Whale Meat Supplies

In 2011 Japan's stockpile of whale meat reached a record high of more than 6,000 tonnes. In 2013 whale meat consumption fell to around 2% of its peak of 226,000 tonnes in 1962, when it was the country's major source of protein.

The government has reportedly spent three billion to four billion yen (US$30 million to $40 million) a year into the the national whaling operation, despite the falling demand for whale products. According to the International Fund of Animal Welfare "whaling is an unprofitable business that can survive only with substantial subsidies and one that caters to an increasingly shrinking and ageing market".

To help increase sales of whale meat the Institute of Cetacean Research distributed 7,000 brochures in 2013 to promote consumption of whale products among Japan's younger generation. As of late March 2014, more than 2,300 pounds minke whale meat has been stored in freezers, with a lack of buyers nearly doubling over 10 years. Despite this lack of demand for additional meat, Japan is committed to catching another 1,300 whales per year.

Public Opinion of Whaling in Iceland, Norway and Denmark and Other Countries

In December 2013 Iceland Government issued new whaling quotas, allowing 229 minke whales and 154 fin whales to be harpooned each year for the next five years. This decision took place just months after a national Gallup poll commissioned by The International Fund for Animal Welfare found that just 3% of Icelanders had bought whale meat six times or more within the previous 12 months. The poll also revealed that up to 75% of the sample size (1,450 people) never bought the meat. This view was greater among women and youths aged 18-24 years old, with 82% and 86% never touching whale meat.

In a 2009 opinion poll one in three Norwegians said that they believed the government should begin phasing out whaling; 21% said that it was acceptable that hunted whales may take anywhere between several minutes to over an hour to die; and just 7% advised that they eat whale meat on a regular basis while one in five said that they've never eaten it at all.

Greenland and the Faroe Islands, both autonomous regions of the Kingdom of Denmark, both undertake whaling as part of the IWC aboriginal subsistence clause. According to a 2012 WSPA opinion poll only 5% of the Danish population are in favor of commercial whaling and 72% wanted the Federal Government to oppose international efforts to legitimize the practice.

Scientific Research from Whaling

JARPA I & II

The Japanese Whale Research Program under Special Permit in the Antarctic (JARPA) ran from 1987 to 2005 and had four main objectives:

- estimation of biological parameters to improve the stock management of the Southern Hemisphere minke whale;

- elucidate the role of whales in the Antarctic marine ecosystem;

- elucidation of the effect of environmental change on cetaceans; and

- elucidation of the stock structure of Southern Hemisphere minke whales to improve stock management

The Japanese Whale Research Program under Special Permit in the Antarctic II (JARPA II) was launched in 2005 with the aim to:

- to monitor the Antarctic ecosystem (whale abundance trends and biological parameters; krill abundance and the feeding ecology of whales effects of contaminants on cetaceans; cetacean habitat);

- modeling competition among whale species and future management objectives (constructing a model of competition among whale species; new management objectives including the restoration of the cetacean ecosystem);

- elucidation of temporal and spatial changes in stock structure; and

- improving the management procedure for Antarctic minke whale stocks.

An IWC accomplishment involved the establishment of whale sanctuaries in the Indian Ocean in 1979 and the Southern Ocean in 1994, where whales are safe from commercial poachers. The creation of the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary was rejected by Japan, who exploit the "scientific research" loophole to carry out JARPA and JARPA II activities at this location.

The greatest criticism for JARPA programs and Japan's North Pacific whaling schemes known as JARPN I & II, is the killing of such a large number of whales, without properly considering the use of non-lethal means to achieve the same research goals. Suggested non-lethal methods include sighting seeings from a ship or aircraft; DNA analyses based on biopsies; biochemical analysis; and satellite tagging.

Al Jazeera Reports on IWC's Proposed Third Whale Sanctuary (to the annoyance of Japan)

The Institute of Cetacean Research has claimed that Japanese whalers utilize a mix of lethal and nonlethal methodologies, though latter methods are not possible when internal organs are required. The ICR also noted that when a large number of samples are required to achieve statistically meaningful results, nonlethal methods are "impractical, cost ineffective and prohibitively expensive". Lethal methods also have the added benefit of recovering the cost of research by selling the whale byproducts.

According to Marc Mangel, Research Professor of Mathematical Biology at University of California Santa Cruz and Director of the Center for Stock Assessment Research, there are a range of other criticism on JARPA I & II, including:

- overly broad and poor definition of research objectives that allow almost any activity to take place.

- the majority of the work regarding JARPA and JARPA II is published outside the standard peer-review process, and therefore is disconnected from the self-correcting scientific community.

- most of the work that has been published in standard peer-reviewed literature refers to topics that have nothing to do with the set objectives of the JARPA programs, such as the physiology and biochemistry of reproduction in whales.

- the objectives of JARPA II demonstrate confusion between ecological monitoring and management on one hand; and field work and scientific confusion on the other.

- there is no record that Japanese researchers have given sufficient attention in avoiding unintended and negative consequences as a result of JARPA II's design.

- researchers insistence that lethal take of whales is necessary, blurs the line between scientific exploration and resource exploitation.

- no demonstration has been given of how the fieldwork undertaken in JARPA and JARPA II will contribute to the analysis of Maximum Sustainable Yield.

- the potential of JARPA II to contribute to the understanding of conservation and management whales of whales is very low.

Whaling Wars & Clashes at Sea

For decades conservationists have attempted to stop Japanese whaling vessels from achieving a full harvest. So of course there was much celebration between environmental groups following the ruling by the ICJ.

Over the years Japanese whalers have often clashed in the ocean with activists from Sea Shepherd, who have taken a far more aggressive approach than Greenpeace and other conservation groups. Their tactics involve hurling tubs of rotten butter (or butyric acid) at Japanese whaling ships; boarding boats; throwing flash grenades; firing water cannons; covering target vessel deck's with methocel, which becomes ultra slippery if mixed with water; projecting vegetables at specific targets with a giant long range spud gun; disabling boats' propellers with ship foulers; and utilizing long range acoustic devices (LRADs) to disrupt hearing and electrical equipment.

The Founder of Sea Shepherd, Paul Watson, told the Sydney Morning Herald that the decision of the ICJ calling for an end to Japan's whaling in the Antarctic justified the group's often controversial actions when engaging Japanese whalers.

''I am so pleased that after a decade of anti-whaling campaigns in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean, we won't have to go there again,'' he said. ''We feel vindicated. This has always been an illegal whale hunt.''

News report on a clash between Japanese Whalers and Sea Shepherd; and Australia's ability to stop Japanese whaling in Antarctica

How are Whales Killed?

For millenia humans have adapted their methods in hunting and killing whales, with constraints including available vessels, methods of vessel propulsion, distance from safe harbor, and availability of industrial technology.

Though the first organised whale hunt occurred in 700AD, the earliest known record of hunting, capturing and kill whales dates back to 6.000 BC in South Korea, where carved drawings were found depicting Stone Age people hunting whales with boats and spears. Through out the centuries other whaling tools include:

- nets

- spear guns, which were first created in 1731, but became more popular in the 19th century;

- lances, that were thrust into the whale's vital organs;

- darting or Pierce guns, created in the U.S in 1865 to fire harpoons, lances and explosive lances into whales with greater accuracy than shoulder guns;

- exploding harpoon cannons that were created by Svend Foyn in the 1840s and ushered in the modern whaling age;

- swivel guns;

- Greener guns, a bow-mounted, swiveling harpoon cannon created in 1837;

- cold grenade (non-explosive) harpoons, made with empty grenade casings;

- bomb lances, which were first used around the mid-19th century and were filled with explosives that would explode soon after entering the body of the whale;

- shoulder guns, that were used in the 19th century to fire bomb lances and were known for their lack of accuracy;

- various caliber rifles (often used as a backup weapon in case harpoons don't kill the whale instantaneously);

- electric lances (once used in Japan as a back up weapon when explosive harpoons damaged much of the whale's tissue but didn't strike vital organs. It involved shooting electricity through the whale's body);

- whaling crossbows; and

- black powder.

Indonesian fishermen harpoon a whale

Penthrite Grenades

Today the more popular instrument used to kill a whale is penthrite explosive grenades, which are often accompanied by secondary weapons, such as large caliber rifles. They were first adopted by Norway in 1983-1986 as a replacement of cold grenade harpoons, which were seen as cruel by prolonging the suffering of the target. Killing the whale faster also decreases the "struck-and-lost" rate, where the whale escapes after being shot. Testing of penthrite equipped harpoons in the mid-1980s on 259 minke whale, showed that they were instantly lethal 45% of the time, with the median time till death being 72 seconds.

Japan uses 50mm or 75mm harpoons charged with different quantities of penthrite explosives depending on the type operation and species of whale (ranges from 30-60 grams of penthrite). A secondary back up weapon is sometimes used, which can include another shot with a cold or explosive harpoon or a large calibre rifle. Boats are equipped with sonar equipment and two winches to haul whales on board.

Whale Drives

A totally different method used in the Faroe Island during their hunts for long finned pilot whales involves the use of boats to drive whales into shallow water or to beach themselves (the hunt is known as Faroese grindadráp). Instruments used include loose stones (leysakast) and stones tied to a rope (fastakast) that are thrown into the ocean to frighten the whale to swim in the desired direction; spears (hvalvakn); hooks (soknarongul); knives (knivur); and hand-held harpoons (skutil).

When the whale has beached or pulled close to the boat with the use of the hook, a whaling knife (grindaknívur) is used to put the whale to death by cutting deeply into the whale's flesh, slicing the creatures spinal marrow and forcing it to convulse so fiercely that it severs its own spinal cord. The animal dies in around 30 seconds.