- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

Conquest - 18: Domesday Backcloth - Marriage En Outremer, Outsiders' Mix With English

Integration was the aim - whet nurses, servants and household staff were usually English, Norman offspring learned their tongue from an early age

Marriage between the incomers...

Normans, Franks, Flemings, Bretons and the indigenous population was more common than surviving sources would have us believe.

At the lower levels of society mixed marriages were unlikely to be recorded at all, especially clerical marriages (priests or other church men to English women), frowned on by the Church hierarchy. Priests were meant to be celibate from the time Lanfranc was made Archbishop of Canterbury. English church men were given an ultimatum, to repudiate their families or leave the Church. Many repudiated their families in order not to have to surrender status, even parish priests.

The marriage of Odelerius of Orleans was recorded by his son Orderic, a gifted historian who wrote down the names of his father and brothers, although not of his English mother (!) Henry of Huntingdon was a secular chronicler who referred to the wives of clerics. Most are described as concubines or by euphemisms. Marriages to English women were not only entered into by lower clerics. Rannulf Flambard, Bishop of Durham from AD1099-1128 had many children by Aelfgifu, who came from the same burgess family of Huntingdon which brought forth the hermit nun Christina of Markyate (Christina was a name brought to England in mid-11th Century when Eadward the Confessor's cousin, Eadward 'the Exile' brought his family from Hungary after many years away. His youngest child was named Christina). Rannulf Flambard later arranged Aelfgifu's marriage to a worthy from Huntingdon and often stayed at their house on journeys to and from the north. He took care to provide for his sons and nephews, and his descendants were still to be found holding land in the 13th Century.

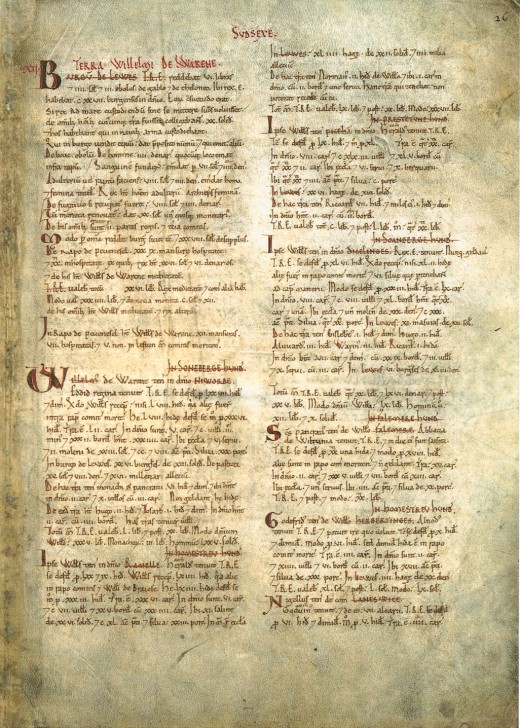

Orderic Vitalis, a Norman chronicler who spent his early boyhood in Shrewsbury observed mixed marriages in an urban context, stating that in the 1070's English and Norman lived peaceably as neighbours in boroughs and cities, also intermarrying. His words are borne out by Domesday*, wherein Frankish settlers are recorded as living at Southampton, Wallingford, Hereford and Shrewsbury, and at Cambridge. An update made around AD1100 to Domesday accounts of Gloucester and Winchcombe distinguishes between burgesses living in inherited tenements and those who recently bought their homes - at Gloucester a number of the latter were Frankish. The description in Exon, or Little Domesday of the new quarter of Norwich is headed 'Franci de Norwic' (Frankishmen - or Frenchmen - of Norwich). The new borough was founded by Earl Ralph II and the king and originally housed thirty-six burgesses on the king's land alone, and another eighty-three on the lands of other lords besides an unoccupied 'messuage' (a dwelling-house with outbuildings and land). A church founded by Earl Ralph also stood here, At Nottingham and Northampton there were also new quarters, the former including houses built for Hugh fitzBaldric, sheriff of York. After the rebellion in AD1069 most of the riverside dwellings York close to the sites of the castles were destroyed. The Normans had tried to clear a swathe around their wooden castles, so that the rebels could not use them as cover to attack them from. The fire could not be contained and destroyed much of the cathdral church of St Peter (now known as the 'Minster').

New blood?

It is not out of the question that Normans and their Breton or Flemish allies who came with Duke - later King - William should seek to marry English women. After all, there would have been a shortage of their own womenfolk to choose from, and their lords would have first pick of indigenous women or brought their own wives. On the other hand after the various battles between 1066 and 1071, England had seen many men slain in the shield wall and elsewhere, and many who were dispossessed left these shores for the east - see the Hub-page in the VIKING series on the Varangian Guard - to fight the Normans in the Mediterranean.

Norman blood was not altogether new to England, after all. Their cousins from Denmark and Norway had already settled in the east (Danelaw) and North and mingled with the Anglian women in neighbouring communities. Many English women preferred the Danes because they washed more often, and combed their hair. Now these Normans with strains of Gallo-Norse blood in their veins introduced a new aspect of breeding with their taste for cider and wine, their shorter hair etc., and although their mothers may have frowned on the incomers many lonely abandoned or widowed women would have welcomed the change... 'Any port in a storm'.

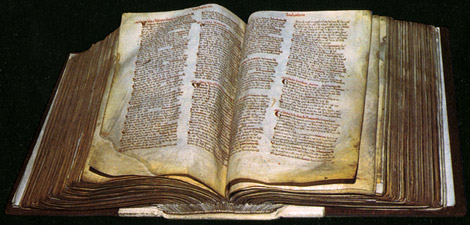

The original was set out in Latin. This translation lifts the lid on the possessions of William's lords and those of his indigenous nobles - the few that still lived - to show who owned what and where, who owned it before (with the exception of Harold himself). There were two main books, 'Exon Domesday' covered the West Country - formerly Wessex - broken up into smaller shires and Church holdings. Where a Norman lord's territories seemed 'bunched together', he might be relieved of some here and given more there. William had a fear of lords gaining power at his expense, as had happened in Normandy before his majority. His Norman barons had it their own way at home, here things would be different

Domesday - Demesde, the book of the (king's) domain

Domesday Backcloth

A classic misunderstanding: Down through the centuries the term 'Domesday' has been linked with 'Doomsday'. In many respects the link is understandable, as it often led to higher taxation. The term is 'Demesde', to do with all property including that held by church or secular landlords. Even the new Norman/Frankish/Breton lords were not immune to taxation levied as a result of its findings.

Why was 'Domesday' initiated at all? William I was informed of an invasion planned in AD1085 by Svein Estrithsson's second son Knut II, 'the Holy',who wanted to revive the Danish claim to the throne of England. On the levels of taxation he was due on property, the funds fell short of what were needed to raise an army and fleet to turn the Danes back. There were two sets of books, Domesday itself encompassed much of the kingdom, Exon Domesday incorporated the west country. As Durham was traditionally Church land it was omitted. Difficulties met in the wild north led to the lands north of the Tyne being left out, although it was considered the yield from these lands and much of those between the Tees and the Humber would have yielded insufficient funds due to them having been harried in AD1069/71 and were still largely barren in 1086. As it turned out Knut was prevented from joining his invasion fleet due to threat of attack from the south. Led by his brother Olaf a rebellion of Danish leaders was initiated because they felt his invasion to be a lost cause. He was pursued by the rebels and murdered in the cathedral of Odense. The books are on archive at the Public Records Office at Kew in Surrey, near Richmond

Next - 17: Naming Heirs

© 2011 Alan R Lancaster