Learning from the Japanese-American Internment Camps

Principle over Fear and Prejudice

The United States has always been blessed by geography. With large oceans to both the east and west, Americans through much of our history have felt safe from the outside world. Sure, the United States was involved in conflicts much of the time. In the 19th century, this usually involved fights with Native Americans, but only people who lived near the Western frontier line felt directly threatened. And when the United States adopted a more aggressive foreign policy beginning in the late 1800s, the fights were always somewhere else. The United States has not engaged a foreign power in the continental United States since the War of 1812.

This isolation from conflict is one of the reasons why Pearl Harbor was such a shock to the system. Sure, this was a quick air raid 3,000 miles away from the West Coast, but for Americans used to wars that were always somewhere else, it felt far too close to home. As the Japanese then proceeded to capture territory all over the Pacific, it was not unreasonable to think that the West Coast was under threat. For the first time since the Indian Wars, civilians on the American mainland might find themselves in a war zone.

The story of what came next on the West Coast has become more widely known than when I was a child. I did not learn about the Japanese-American "internment" camps - although I prefer the term prison camps - until I was in college. Although the United States did not officially admit any wrongdoing until 1988, it's clear that the country in general was not proud of this particular episode during World War 2. Understandably, people preferred to remember the heroic efforts necessary to defeat the Japanese and the Nazis. We did not want to admit that in a war where democracy and freedom defeated tyranny and racism, the United States put people into prison simply because of their ethnic identity. A country that played an important part in stopping the German death camps had its own concentration camps during the war.

This may sound harsh. Yes, Manzanar was not Auschwitz. Japanese-Americans were held in camps for about three years and then released. They were not being massacred in gas chambers. Most Americans, however, would like to think that the United States is more than just "better than Nazis." The United States is supposed to be a place where rule of law applies equally to all. It's supposed to be a land guided by the principles in the Bill of Rights, a place with due process and where people are innocent until proven guilty. But if you were Japanese-American during World War 2, the United States adopted the "better to be safe than sorry" principle. Since Americans did not know which Japanese-Americans might be disloyal and were a threat to commit acts of espionage or sabotage, President Roosevelt, by executive order, decided to lock 110,000 people up: men, women, children, the elderly, whether citizen or non-citizen.

It is fairly easy to uphold noble legal principles when a country is relatively safe and prosperous. Americans have been content throughout their history to emphasize freedom over security because most of the time, they have not felt threatened from the outside. But then, at the first sign of possible attack or invasion, the Bill of Rights was thrown out the window. It makes one wonder how much Americans have every really believed in those noble principles in the first place.

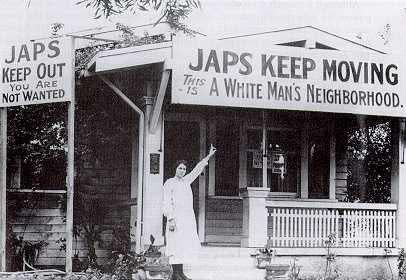

It is tempting to look back at the internment camps as an anomaly. During this time of unusual stress and fear, the government (and much of the country in general) overreacted. Eventually, the federal government acknowledged that it had done wrong, and hopefully, a similar mistake will not be made again. The problem with this argument is that the internment camps were not particularly unusual or surprising. Ever since significant numbers of Japanese-Americans had begun arriving to the West Coast in the late 19th century, they had faced various forms of prejudice and discrimination: job discrimination and bad work conditions; segregation; restrictions on their ability to immigrate into the country, own land, or become naturalized citizens; and the types of stereotyping and general hostility faced by ethnic minorities throughout American history. Since they represented a small percentage of the overall population, and they were seen by the majority as foreign outsiders rather than "real Americans", Japanese-Americans were especially vulnerable when a country where the majority of them had never lived went to war with the United States.

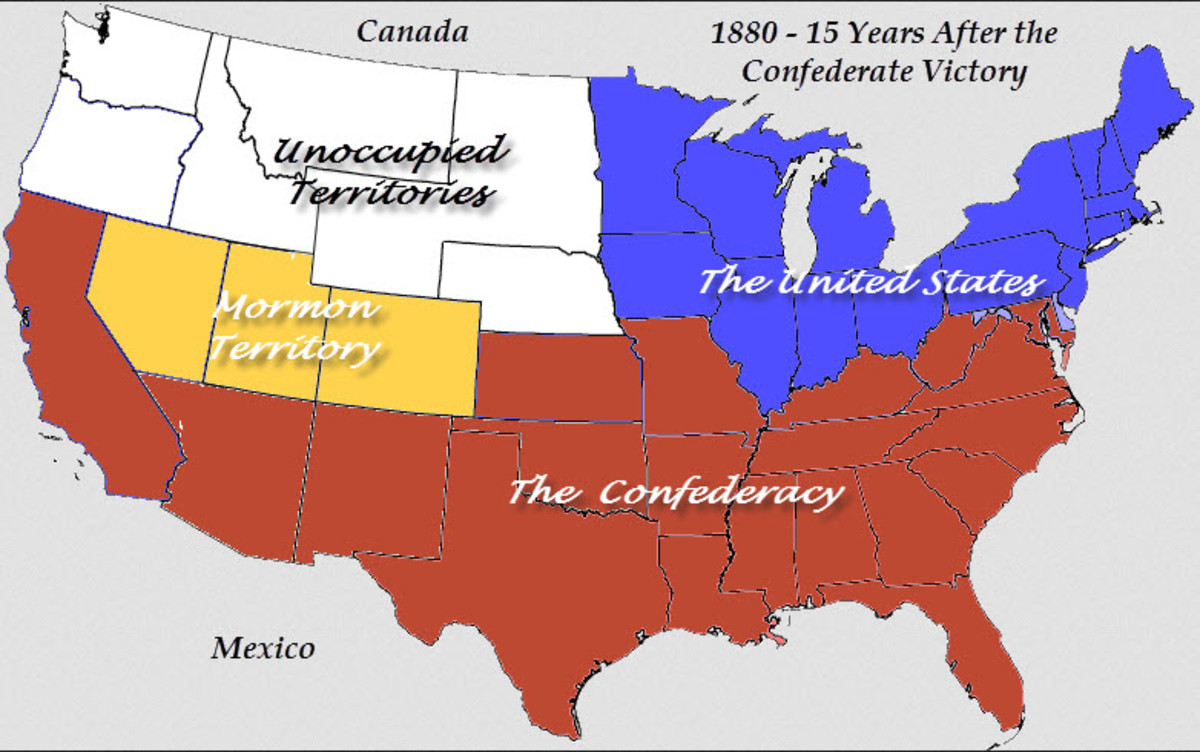

Some would argue that the internment camps were not a product of racism. Sure, they may have been a mistake, but they were the result of an overzealous desire to be safe. But if this was primarily about safety, then why weren't people of German or Italian descent rounded up (in any significant numbers) too? And how can anyone possibly believe that there was no correlation between the racist laws of the early 20th century and the specific targeting of Japanese-Americans during the war. The simple truth is that the Bill of Rights has never applied equally to all Americans. When the nation was founded, equal rights only applied to white males, and in many states, white males with property. Women were second class citizens, slaves had no rights whatsoever, and Native Americans and (eventually) Mexican-Americans were seen as obstacles to be pushed out of the way. With racial attitudes having improved little by the early 1940s, the internment camps were not an anomaly. If anything, they were the norm. World War 2 merely brought these racist attitudes even more to the surface, and many Americans were happy to support "internment" so that they could confiscate some of the land, homes, or businesses of those (often annoyingly successful) "outsiders." When Japanese-Americans were eventually released, many had to start their lives over.

Fortunately, things have improved since the civil rights movements of the 1960s. Today, people of various Asian backgrounds are often seen as a "model minority," as people who have become on average wealthier than the white majority through a combination of education and hard work. Still, I have been telling my classes for years to be on the lookout for a backlash against Asian-Americans, largely because of this unprecedented level of success. As Jewish people have known for centuries, it can be dangerous to be a successful minority.

As with all ethnic minorities in the United States, there is a long history of prejudice against people of all Asian backgrounds. Some of this lingering prejudice may be bubbling to the surface right now, with the United States attempting to bring under control the corona virus, a disease that originated in China. With tensions building, so are the number of Asian-Americans complaining about hostility, both subtle and overt, being directed toward them from both the government and the general population. Needless to say, prejudice of any kind is disturbing, a fact that is hopefully not lost on all of us. It can be tempting to jump on the bandwagon when another group is being criticized. But if a climate of prejudice and racism is tolerated, then it might be your ethnic, racial, sexual identity, or religious group that is targeted the next time.

I'd like to think that if I were living in California during World War 2, I would have stood up and said that it was wrong to lock up Japanese-Americans. It is almost impossible, however, for me to put myself in the shoes of people living in those times. Would I have rallied around the flag, given in to fear, and/or been influenced by the racial prejudice all around me? Would I have opposed internment but been too scared to say anything about it? Would I have put myself at risk and opposed a policy that had no direct impact on (and might even benefit) me? We are not living right now through anything remotely comparable to World War 2. But this could be a time when those of us not facing hostility at the moment will stand up and be kind to all of our neighbors and call out any racism or prejudice when we see it. In recent years, prejudice against various groups has been bubbling up to the surface once again. Let's not let fear and prejudice get the better of us and lead us back to the mistakes made by our ancestors. Let's have the courage to stand by the Bill of Rights even when we are scared.