Change in Higher Education -- Why is Tenure Disappearing in American Universities?

Recently after reading my hub about the process for promotion and tenure at the university where I work, one of our HubPages authors, Paul Kuehn, asked me a couple of questions. Here is my expanded response.

Paul's Comment --- I never realized that the [promotion and tenure] process was so detailed. When I went to college, I thought it was simply "publish or perish" to gain tenure. Is this process for getting promotion and tenure the same in other countries like England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand?

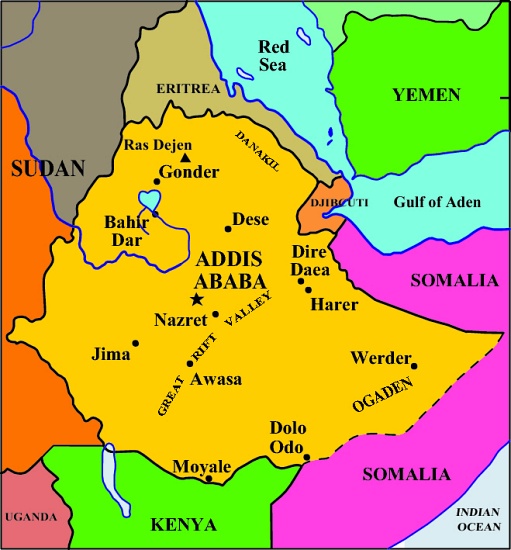

My Response --- It is definitely a lengthy, detailed, and strenuous process. I wish I could answer your question about England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, but unfortunately, I don't know anything at all about P&T processes in other countries. It may actually be quite different. Perhaps those of you on HP who have experience in those nations will address this question.

And I should qualify that the promotion and tenure process which I described applies to a particular small private university in the southeast and may not represent the average faculty experience. Large state and private universities do have "publish or perish" processes and policies. At those institutions, 75% of tenure is based on publications and 25% on teaching and service.

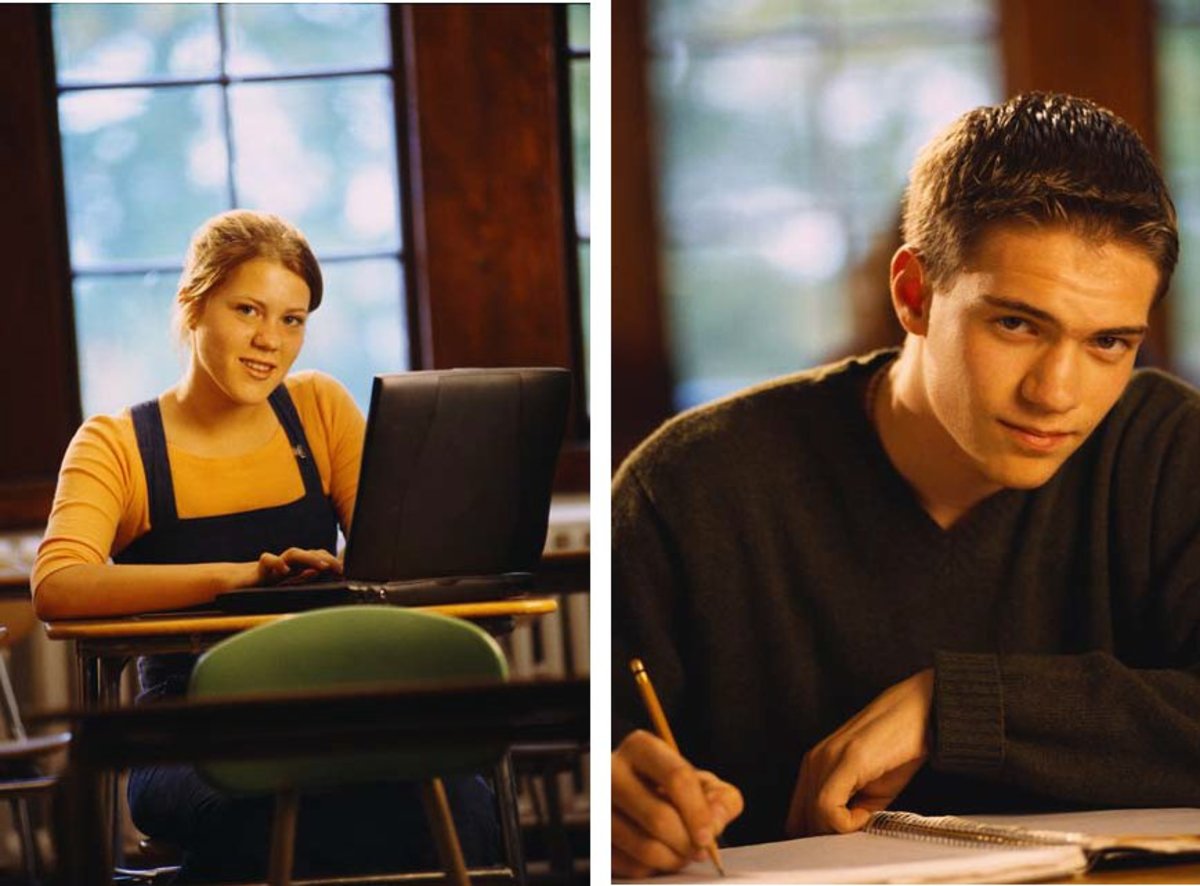

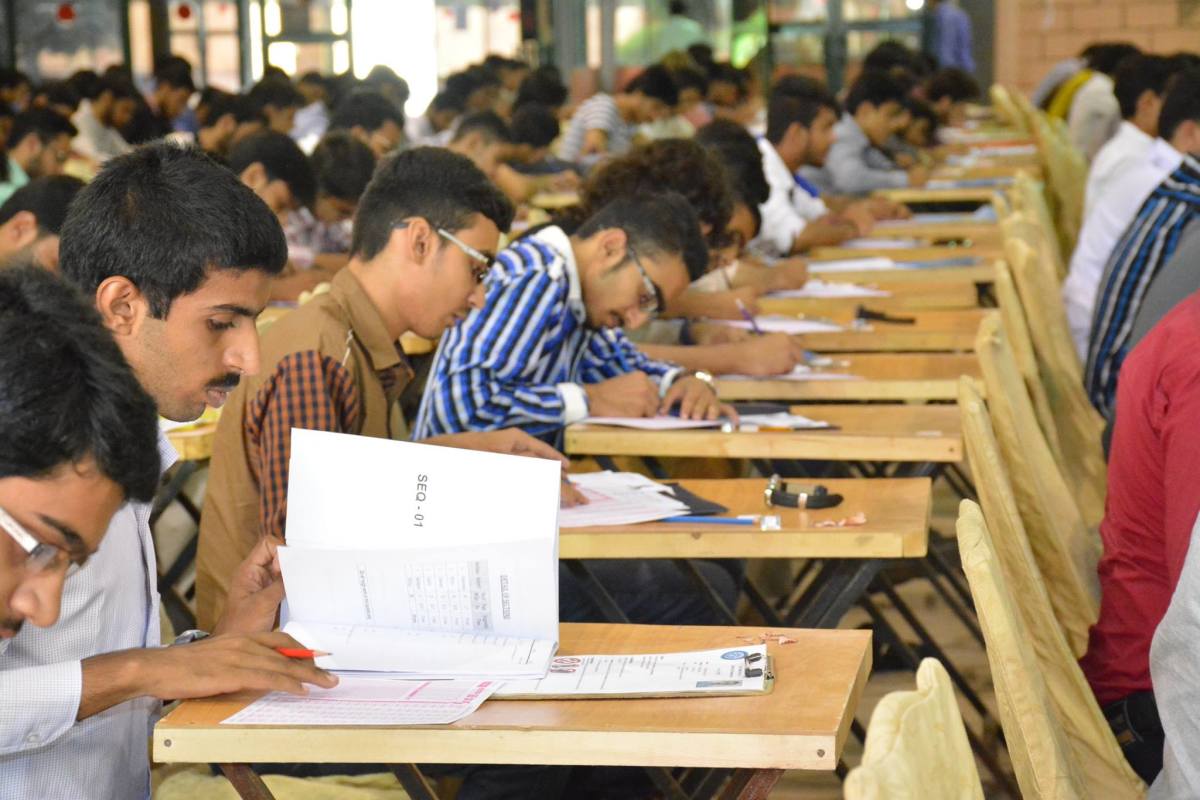

These “publish or perish universities are also institutions where some of your children are students in classes held in lecture halls with 100 to 400 seats. Tenure track faculty may teach one or two of these classes (graduate student assistants grade the exams and papers) and devote the rest of their time to research and publication, which they have to do if they want to retain their position. I would not want to go to college there and I would not send my children, but obviously, lots of people do.

The other extreme with respect to tenure can be found at medium to small sized state colleges and universities, both public and private, many of whom have been slowly eliminating tenure over the past thirty to forty years. There are two major reasons that I am familiar with which are often given for the shift away from tenure in higher education.

(A) There seems to be a lot of misunderstanding and resentment in the United States about what academics actually do, how much what we do is worth, and how much we are paid. I cannot tell you how many times I have heard someone say. Well, those who "can" do and those who "can't" teach. Or the number of times I have heard some ill-informed person pontificate publicly. Well, they teach five classes a semester, so they are in the classroom a whole 15 hours a week, and we pay them WHAT?

Yes, I stand in front of my students 15 hours a week and I meet with them 5-10 hours a week in my office, and I spend about five hours a week in academic meetings and writing various reports. And we can all add, so I get a fabulous salary (I did a hub about the common misconceptions about college faculty salaries) for working 25- 30 hours a week. (It is best to be amused by, rather than irritated by people who think like this. If they have never worked full-time for a college or university, they are speaking from outside the system and probably don’t know any better.)

Whether in or out of the office, faculty must also spend many hours a week devising the guidelines for and grading exams, reports, essays, research papers, group projects, and daily quizzes. Faculty read books, take detailed notes, prepare lectures for their classes; they design brand new courses occasionally and shepherd them through a lengthy academic approval process; most faculty serve as mentor to one or more student organizations; we organize on-campus conference, plan academic colloquia, locate and bring civic, academic, and religious speakers to campus; we work on our own research projects and present papers at local, state, and national conferences. A recent independent study found that American faculty on average work between 45 and 50 hours a week, obviously some only put in 40 hours and some (often tenure track) put in 55.

To return to reason (A), academics are well - respected in Europe, to a large extent they are disrespected in America. Some scholars believe this can be traced back to our early colonial history. We all study about America the great land of opportunity where hard-working business entrepreneurs could succeed, and indeed the colonies were and America still is that place. But as our text books tell us, in order to succeed the colonies had to break away from aristocratically-ruled England where only the aristocrats had access to higher education.

Throughout Europe the aristocratic upper class (who by and large inherited their property and wealth and were not capitalists) was the educated class and of course, both resentment and disdain developed in America for the spoiled, lazy, educated, inheritors of titles and lands. When our fore fathers chose to specifically eschew the use of titles, the die was unintentionally cast which would lead to distrust and derision for those who make their living by the life of the mind, as opposed to by honest common labor. There has been a continuing strain of anti-intellectual rhetoric in American politics and business. Richard Hofstadter, "Anti-Intellectualism in America" has been around for quite a while, but Hofstadter is a well-respected historian and he and others address this issue in great detail.

(B) Finances, everything comes back to money doesn't it? As state budgets have been squeezed and as educational funds for higher education from Washington have diminished (not necessarily as a discrete number of dollars, but as a percentage of budgets), colleges and universities have not surprisingly been desperately looking for ways to cut costs. Of course, as is true of most businesses, a major portion of any college or university budget is employee salaries and benefits. But you have to have professors and teachers in the classroom, don’t you? (distance and on-line learning is another whole topic and it has been written about on HP by both supporters and detractors)

True, but class sizes can be increased, if the structure of the building permits expansion of class-room size, and in many cases the buildings do. So, often this is a major area where university administrators and college presidents make cost reductions. Their desire to eliminate faculty may be stymied by the regulations which govern promotion and tenure, which are spelled out in detail in the Faculty Handbook, a document which is binding. Not being able to fire tenured faculty at will, based on their personal discretion poses a difficulty for some academic presidents. [Reason 1 -- Why academic administrators and Boards of Trustees may work to minimize or eliminate tenure.]

On the other hand, if administrators do not choose to increase class size (substantial academic research has demonstrated that large classes to not benefit students and often decrease learning and retention), they can change how they staff classes. Classes can be staffed with full-time (FT) faculty who receive both wages and benefits or with adjunct (PT) faculty who teach part-time, often at two or more locations, who only receive wages.

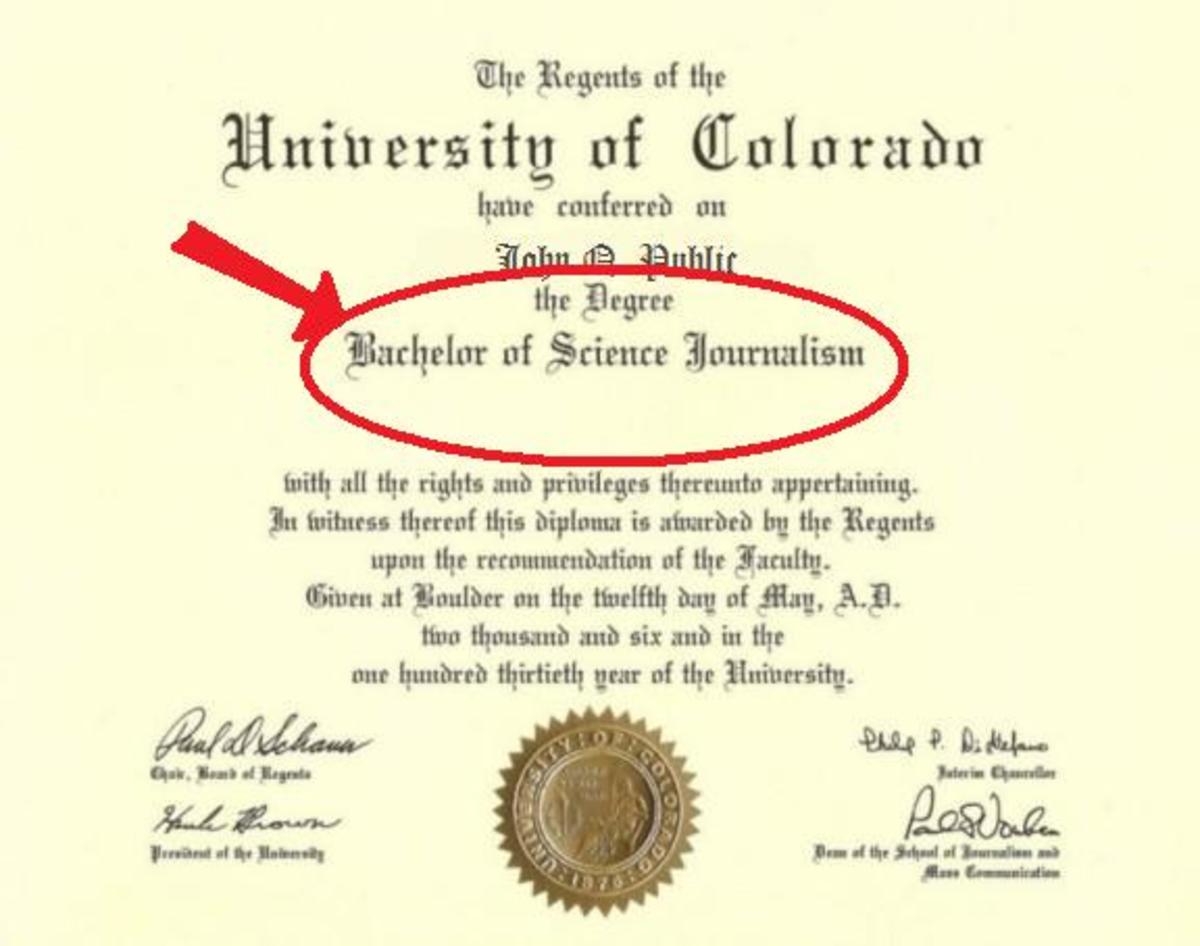

In the southeastern United States, adjunct faculty are generally paid 1500 to 2500 dollars per course. So, adjuncts teaching five classes per semester will make between 15 and 25 thousand a year. No benefits, no medical, no retirement, no contract – they are hired on a semester by semester basis - and they all have a Masters degree in their discipline and many of them have earned a PhD as well. [Reason 2 -- Why academic administrators and Boards of Trustees may work to minimize or eliminate tenure.]

The employment of large numbers of adjuncts to teach a class or two here and there at different colleges, is detrimental to both adjuncts and students for a whole host of reasons beyond the scope of this hub. Utilizing more adjunct instructors and fewer full-time professors does indeed save money, but to accomplish that goal university presidents often have to weaken or even dismantle the tenure process.

Tenure does protect faculty who have spent years at an institution and have remained productive at a very high level in the areas of Teaching and Advising, College and Community Service, and Research, Conference Presentation, and Publication. However, tenure also protects our students and insures that they receive a quality education from faculty who will be there to work with them semester after semester.

Much learning is based on continuity and building relationship, things that students cannot achieve with adjuncts who may be here today and gone tomorrow. I say this with the utmost respect and concern for adjunct instructors; they are not itinerant instructors by choice. Ninety-five percent of them hope to secure a permanent position somewhere. I have personally known many excellent and dedicated educators who were adjuncts rushing between two, three, even four locations to teach courses. Sometimes this sort of teaching schedule and regimen continues for many years. Some adjuncts never secure a full-time position.

I do not sympathize with adjunct faculty because I merely imagine their struggles, exhaustion, and frustration; for two years at the beginning of my career I was an adjunct instructor driving all over the metro Atlanta area to teach courses. By teaching thirteen – fourteen courses a year (8-10 is standard), I earned around twenty-three thousand a year and was able to take care of my three children. Adjunct teaching ought to be for the young, the strong, and preferably, the unattached.

Issues in Higher Education

- Are You Going to College? Get Great Recommendation ...

Completing applications for college and university is important Good recommendations from your teachers and professors can mean the difference between getting accepted by your last choice or your first choice institution. Where do you really want to - Why Do Professors Teach the Way They Do? How do I T...

How should we teach? Why do we teach? What should we focus on in high school and college? What skills do we consider important? What objectives do we have in mind as we prepare to go into the classroom? Money is not the answer, although it helps. The - Benefits of Working at a College or University

Employees consist of cleaners or custodians, maintenance workers, grounds keepers, public safety, office workers, professors and so on all the way up the food chain to the President or Dean. When visiting a College or University you will notice that - Full-Ride College and University Scholarships - Grea...

Few students can attend college without some sort of financial assistance. There are Pell grants, a variety of loan programs, and there are institutional scholarships, both need and merit based. But how much of the total cost of a college education s - Melbourne University Education in Australia.

Education in Australia-In recent weeks there has been considerable publicity here in Australia and more so in India about attacks on Indian students. Student attending Australian colleges in the State of Victoria have been subjected to various... - The University Promotion Process - How Professors Ea...

People outside of an academic setting often have questions and doubts about the meaning and utility of Tenure. And what is a university promotion process like? How and when do college faculty get promoted in rank? What is rank? The process leading to - Tips: Choosing the Right College or University For Y...

Making the leap from high school to college is one the most important transitions in one's life. There are many difficult decisions that lead to this next level. Just imagine, you have to decide what you plan to spend the next 30+ years offering... - Just How Filthy Rich Are Those Arrogant College and ...

The cost of a college education has been rising. What about the generous salaries earned by professors? Are their salaries unreasonable? What kind of salaries do other professionals with less education and training earn? So, what are some of the caus