Mastery of Learning: Ease Your Educational Journey

A couple of evenings ago, I was conversing with a newly acquainted entrepreneur and software developer. When he described his work routine to me, he talked about how he would often work on a big piece of code without a solution coming up. He told me about how he would then leave his computer and just go into a blank state of doing nothing in particular and even drifting off to sleep. As his consciousness slowly vanes, the solutions for how he should manage a certain function or write a piece of code pops into his head, and he goes back to work mode again.

Learning what I have learned, I immediately recognized what he was talking about: the modes of thinking. In this piece, I’m going to share with you the most useful facts, techniques, tips and tricks I learned via the LHTL course.

Learning and studying is conventionally defined in a very one dimensional manner. It is thought of as reading a lot of books, and having a lot of information on hand in your memory. However, in order to be an effective learner in any field, you need to keep an open mind to different types of information input, and know how to use your brain most effectively. Your brain is an amazing machine, but like any other machine, it won’t reach its full power or potential if you don’t know how to utilize it properly. You can think of this article as a starter’s guide to your brain. Let us begin.

Know your modes

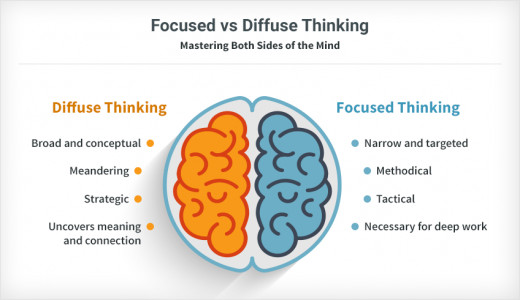

Do you sometimes find yourself daydreaming during a particularly boring lecture? Or perhaps find a solution to a particularly hard problem after a workout session? These are the miracles of your different thinking modes at work. The first of the two modes is focused mode, which is activated when you’re actively engaged in doing a particular task or solving a certain problem. In this mode, the brain searches through familiar thought patterns in order to find the solution that is required. The second mode is known as diffused mode and it turns on when you’re in a more relaxed state of mind. In this mode, the thought patterns are activated in a random order, hence this mode is more applicable while doing creative work or coming up with solutions to novel problems. As you learn, you need both these modes in order to learn new concepts and practice problems in order to cement your learned knowledge.

Procrastination and The Pomodoro

We all have experienced it: that one assignment we don’t want to tackle, or that chore you don’t want to do. Do you know that when we don’t want to do something, we actually feel physical pain? This is because the pain receptors in our brain are activated when we face an unpleasant task. In order to avoid this pain, we turn our attention to more pleasant tasks. This is how procrastination works.

To understand how we procrastinate, we also need to understand habits, and the mechanism through which they are formed. Habits have four components. The cue is a certain sensory, physical or mental signal: it could be something you see or hear, or even something you feel in reaction to an external event. The routine is the core habit that you actuate in response to the cue, and the reward is the positive reinforcement of feeling good that you experience after the routine. These three parts are under-laid by belief, either misplaced or miscalculated.

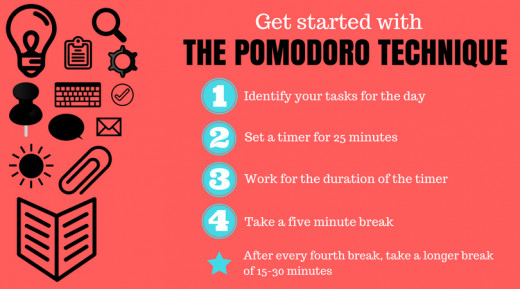

In order to counter procrastination, you need to exert some willpower to change your reaction to the cue. You also need to focus on the process, and not the product. Divide the final goal into smaller processes, and you can more easily focus on achieving them instead of being daunted by the prospect of achieving the final product. A common method to utilize is the Pomodoro technique: set a 25 minute timer, remove all distractions and work for 25 minutes straight. At the end of the timer, set a small reward for yourself such as some mindless browsing or a little snack. As you get proficient in this technique you can alter the timings to your liking. Don’t increase the duration too much though: you don’t want to let distractions and emotions get the better of you and dissolve your mood to achieve targets.

Memory and Chunking

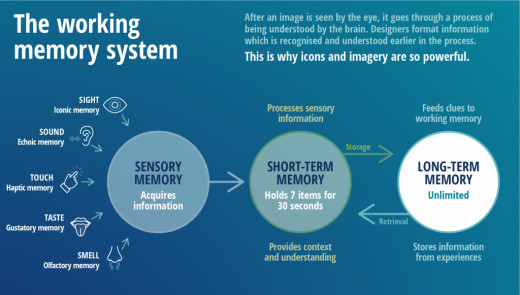

Our brain has two types of memory. Working memory or short term memory is like a whiteboard or a computer RAM module, where currently processing information is stored. This information fades or disappears quickly as it gets replaced with new information when you switch tasks. This is why you also need long term memory: this is similar to a filing room or a computer hard drive where you store your memories. Memories stored here don’t get erased easily. However, they do get re-consolidated, which simply means that they are slightly altered (or more aptly, compressed) as you continue to retrieve them.

Since a considerable part of your brain is dedicated to visual and spatial memory, you can increase your memory power by mapping ideas to visual cues, and make them even more memorable with vivid and funny colors, smells and textures. The memory palace technique is one such method, whereby you take a list of unrelated items or ideas, and then place them in different parts of your “palace”. Your memory palace could be anywhere from your home to a library or a favorite park. Next time you go out shopping, try this method and see how many items you can remember. You might be amazed!

Research shows that our brain has four slots in the working memory. This is analogous to running four threads in a computer RAM: you can run up to four parallel thought processes. In order to form coherent thoughts from the content you absorb and learn, it needs to undergo chunking. This is what gives meaning to the content, and places the content in relation to everything else you know. Going along with our filing room analogy, chunking is what decides where to file the different pieces of new information you receive through learning. For academics, you need to fulfill three prerequisites for chunking: complete focus on the content, proper understanding of the material and regular practice. A common example of chunking is memorizing a phone number: you learn the number in threes or fours, you probably find yourself closing your eyes to focus, and you keep repeating the number to yourself until you can write it down or store it in your phone.

More good learning habits

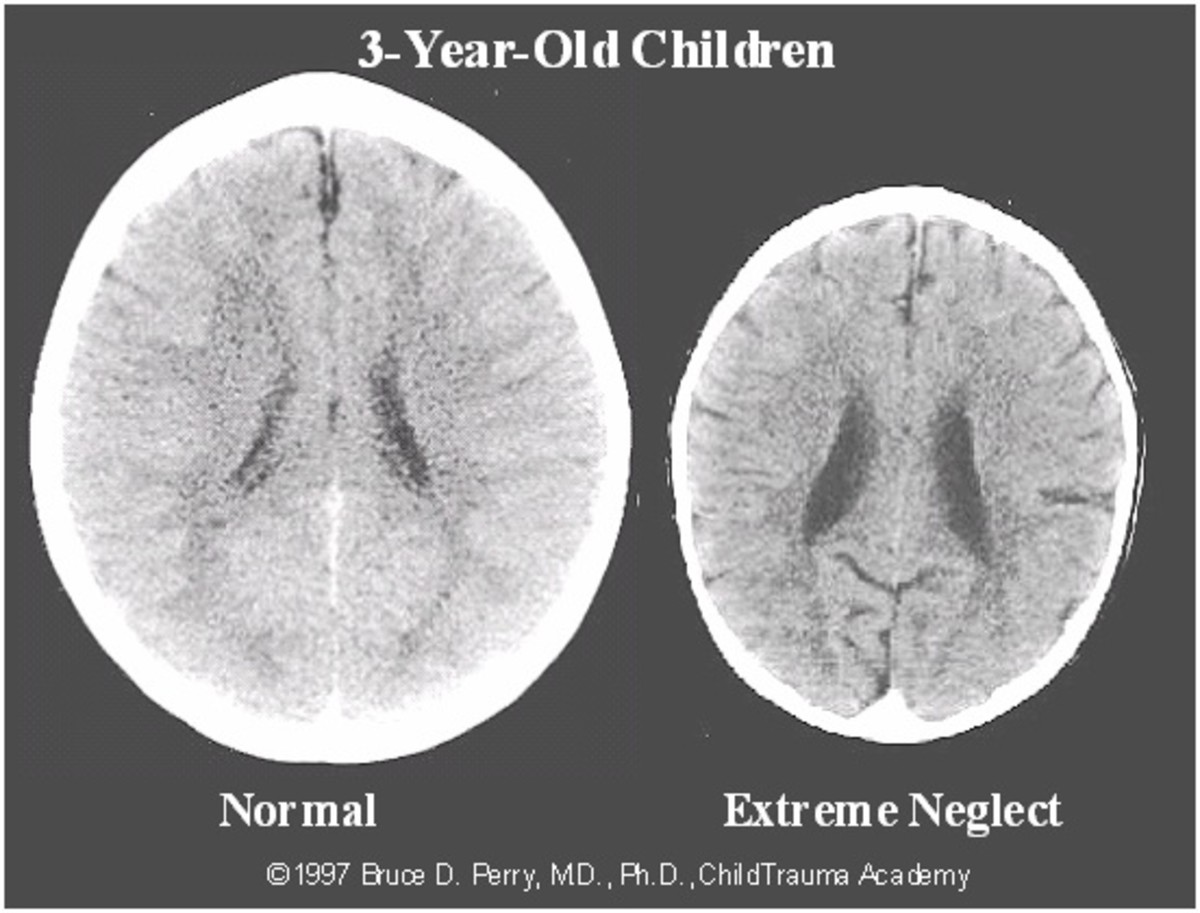

There are a lot of things we can further do to improve our learning capabilities in any field. Sleep is one of the most important factors among them. During sleep, neurotoxins in the brain are cleared, and the neural connections that you form during waking hours are cemented and strengthened. So if you’re staying the night before exams, reconsider: the excess toxins may cause your brain to malfunction, and cause choking during your paper. Environmental stimuli and exercise also contribute to neural growth which helps you learn better. This is why you shouldn’t simply be focused on poring over books. Take time out of your day and set up workout schedules. Sports and exercise play a more important role in learning and brain health than some of us might think!

Illusions of competence are also a problem while learning. Cramming everything up in one go is definitely not the right way to go: your brain needs time to strengthen the neural pathways of the new information you learn. Too much information overloads the brain, hence the memories aren’t properly cemented in your memory, and you forget what you learned in a matter of days. This is why you need to practice spaced repetition: stretch out your learning over a number of days or weeks, and give enough time for relaxation in between. Remember, proper learning requires both focused and diffused modes!

Eat your frogs first: work on the hardest tasks earlier in the day and tick off the most difficult topics or subjects. Recalling what you learned and testing yourself frequently are very effective, as opposed to continuous mindless reading and excessive highlighting. Engaging in group discussions also helps you learn more efficiently. Don’t multitask: this requires context switching, which reduces the efficiency of what you’re doing. Remember, intensity beats extensiveness.

Mix it up when you’re learning: practice different types of problems in one session so you know how they relate. Practice the harder problems instead working on the easy ones you already know, which causes you to think you have mastered the material when you really haven’t. Choose environments that offer less stimuli that would trigger bad habits, such as a quiet corner of the library. Conversely, you can also learn in various environments, so your memories are independent of environmental cues. Did you know that if you always study in the bedroom, it might be harder for you to recall what you learned in the living room, or even the exam hall? So switch it up: study in different environments.

***

If you’re anything like me, you should be feeling some amount of regret for not having come across this knowledge sooner. There’s no need to worry though. However young or old you may be, these learning tips are applicable not only for academics: these ideas and concepts can be applied in all walks of life, even in carpentry or sports. Keep on applying what you learned, and soon you too will be a master in all fields you set your sights on. Happy learning!