Media Literacy is Not a Checklist

Media literacy education right now

A media literacy study by Breakstone et al. (2019) asked 3,446 high school students whether a given website was a reliable source on global warming. The results were sobering: 96% of students failed to even consider the site’s ties to the fossil fuel industry. Despite a reminder to use search engines, students relied mostly on the site’s aesthetics, tone, and About page!

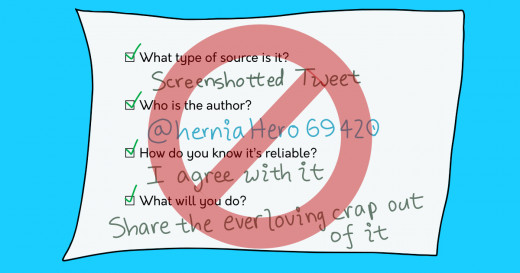

Many of these students learned the same source-vetting I did (Breakstone et al., 2019, p. 27). I was taught the “CRAP detection” model to evaluate a source’s credibility (“CRAP” stands for “currency, relevance, authority, purpose”). We weren’t supposed to use Wikipedia, but Britannica was fair game. Journal articles were the gold standard. Newspapers and books were pretty good. Websites, films, social media, and TV were not.

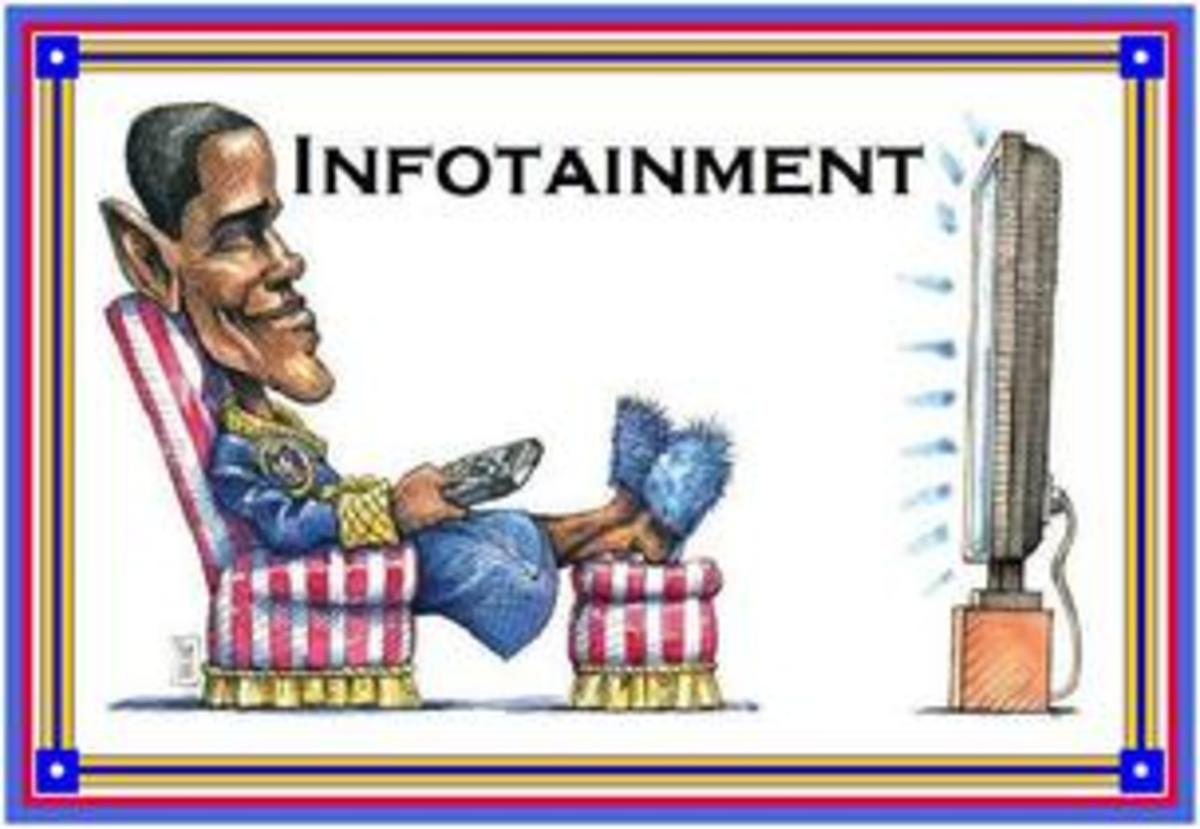

The Breakstone study shows that this “checklist” is not doing its job. Lines between different types of media are blurring. Newspapers are available on the Web, Twitter, and databases (The Washington Post doesn’t even have a paper edition outside DC). Low-quality and predatory academic journals masquerade as legitimate ones. Films, TV, and YouTube videos vary widely in quality and genre. Corporations are setting up think tanks and astroturf websites. Since the rise of The Daily Show, even comedy and journalism are beginning to merge.

We need to get students to think about more than just the “credibility” of individual sources. In this article, I will explore three dimensions beyond the text itself that students need to consider:

-

themselves,

-

the information landscape, and

-

their audience (if sharing or writing about the information).

We’ll dive into each of these one by one. When talking about students, I’ll use the second-person “you” so the phrasing isn’t awkward. (This information may also be helpful for you, the reader!)

1. Yourself

Many of us forget that we’re emotionally and mentally responding to content as we read it. Some of these responses are intended by the author; others are not.

Emotions

How are you feeling as you read the content, and why?

Sometimes the content itself makes you feel something – such as the intense anger many of us felt watching George Floyd’s death. Other times, how you’re feeling before reading affects your perception of the content. Once I learned about George Floyd, for instance, many news stories about COVID-19 didn’t capture my attention.

Many guides to media literacy suggest you downplay your emotions. I don’t: I think emotions are often telling you something important (Lorde, 2007). However, only your rational brain can track down where your feelings are coming from. Pausing to understand this will help you properly account for your emotions as you evaluate what the source has to offer.

Goals

Next, consider why you were looking for something in the first place. Maybe you were doing research for a paper. Maybe you Googled a question that arose in dinner-table conversation. Or maybe you were just scrolling through your Twitter feed looking for entertainment.

In each case, you had a purpose: research, curiosity, entertainment, or something else. Whatever it is, it’s important to restrict your attention to things that meet your purpose. Beware of “shiny object syndrome”!

Ask yourself whether this source looks like a wholesome way of accomplishing that goal. Maybe there’s a more reliable source out there, or a more wholesome form of entertainment (e.g. exercising).

Sites like Google and Facebook also promote content based on how much engagement (clicks, likes, shares) it garners. Be sparing with your clicks; when you click on something, it’s more likely to be seen by others.

Thoughts and beliefs

Next, consider what you already think about the topic being presented. How might this affect your take?

We often talk about biased sources, but rarely about biased readers. Our pre-existing viewpoints affect how we perceive the information presented. For example, readers are more likely to rate information that challenges their beliefs as biased. The effect is even greater when they know the news outlet’s name (Knight Foundation, 2018)!

2. Information landscape

Knowing the information landscape is probably the most valuable part of media literacy. If you deeply understand the topic at hand (on more than one side), you don’t have to rely on someone else’s word. You can evaluate their claims on the merits.

The broader conversation

Any good historian will tell you that, to really “get” a text, you need to put it in context. What are other people saying about the same subject matter? Marlene Scardamalia (2002) put this as, “To understand an idea is to understand the ideas that surround it, including those that stand in contrast to it.”

Academic scholars understand this principle very well – they work in a field where all links between their work and others’ must be explicitly visible. Other content is not so well-labelled, which is why a quick Web search can do wonders for fact checking.

Background knowledge

Background knowledge is probably the most important determinant of whether you really understand a text. For example, it is impossible to read Integrals and Operators by Segal and Kunze without having taken calculus (and several math courses beyond).

Not all background knowledge is so specialized, however. Even just being caught up with the news allows you to put current events in proper context. Consider how an uninformed person might react hearing that corporations received $500 billion from the CARES Act. That’s different from an informed person who also knows that individuals received $604 billion (or knows to look up that number). The latter might still be upset about the first number, but at least they understand the context a little better.

3. Your audience

This section only applies if you’re thinking about sharing an article or write about it for, say, a research paper. But with share buttons and camera phones so ubiquitous, a private viewing can quickly be turned public. (Incidentally, please share this piece!)

Thus, it’s important that you think about the needs and standards of your audience. I personally believe we have a duty to combat the spread of misinformation whenever possible. We should also consider the dangers of elevating low-quality or misleading statements without proper context. The infamous Pizzagate conspiracy theory began with the spread of a false news story on social media. It led to a man attacking a pizza joint with an AR-15 (LaFrance, 2020). Even today, Pizzagate lives on as the QAnon movement (LaFrance, 2020).

If you are someone in a position of authority – such as a researcher, journalist, or teacher – then quality research is even more crucial. Politicians and CEOs (or future politicians and CEOs) may base their decisions on your words.

Conclusion

Thanks to the free market and Internet, the start-up costs of publishing information are very low. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – it’s what allowed you to read this blog, for example. But the sheer amount of information available makes it that much harder for our students to be conscious consumers of information.

I hope I convinced you that the old ways of teaching media literacy are outdated. It’s still important to look at the source material’s credentials. But as it becomes cheaper for low-quality sources to dress themselves up, we need to steer students away from quick-and-dirty checklists. Far better to slow down, take a deep breath, and do the hard work of finding truth.

References

Adams, P. and Romais, M. (2020). Understanding Bias: A Nuanced Approach to a Vital News Literacy Topic [Webinar]. In May News Literacy Webinar Series. News Literacy Project, Chicago, IL. youtu.be/ReNDL-hn-SE

Anderson, W.T. Jr. and Cunningham, W.H. (1972). The Socially Conscious Consumer. Journal of Marketing 36(3) 23-31. doi.org/10.2307/1251036

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., & Saavedra, A. (2019). Students’ Civic Online Reasoning: A National Portrait. Report, Stanford History Education Group and Gibson Consulting. purl.stanford.edu/gf151tb4868

Knight Foundation (2018). An Online Experimental Platform to Assess Trust in the Media. Report, Gallup and the Knight Foundation. knightfoundation.org/reports/an-online-experimental-platform-to-assess-trust-in-the-media

LaFrance, A. (2020 June). The Prophecies of Q. The Atlantic. www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/qanon-nothing-can-stop-what-is-coming/610567

Lorde, A. (2007). The Uses of the Erotic. In Sister Outsider. Crossing Press Feminist Series 53-59. Ten Speed Press, New York, NY. www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/198292/sister-outsider-by-audre-lorde

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective Cognitive Responsibility for the Advancement of Knowledge. In Liberal Education in a Knowledge Society (B. Smith, ed.) 67-98. Open Court Publishing, Chicago, IL. ikit.org/fulltext/2002CollectiveCog.pdf

© 2020 Noah G