Mehmed Pasha: The Fabled "Spider In His Den"

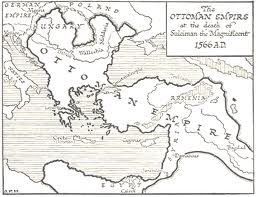

Contained within the pages of Khaled Fahmy’s All the Pasha’s Men is a direct rebuttal of a large majority of acknowledged Egyptian historiography, concentrating on the figure of Mehmed Pasha, the fabled “spider in his den”. Viewed by some academics, such as Afaf Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot, as the instigator of Egyptian nationalism, others, including Henry Herbert Dodwell, place more emphasis on his expansionist incentives. Fahmy furthers the arguments of the pro-expansionist scholars, dismisses the romanticized notion of nationalism, and places the development of early 19th century Egypt within an Ottoman context, portraying Mehmed Ali as an Ottoman reformer striving towards the creation of a “modern army” and correspondingly adapting aspects of society at the state and local level in order to realize his goals.

The unorthodox idea of placing Ali Pasha within the Ottoman context immediately contradicts the hopes of nationalist sympathizers. Contemporary sources as well as modern scholarship reveal that the culture, which the Pasha abided by, was modeled after the Ottoman tradition. The only contestation that the Egyptian governor ever exhibited against the imperial capital concerned the matter in which the empire was organized and ruled, perhaps giving credence to his expansionist goals. But, as Fahmy reveals, there was no true wish towards independence until the year 1838, two decades after the first reforms and the premier conscription of his new army. This fact in and of itself makes the suggestion of nationalism as the prime motivator for Mehmed Ali, a mute point.

While the humble hopes of nationalistic aspirations can be easily denied, the role of Ali Pasha as a modernizer cannot be as simply discredited. Influenced by European and Ottoman military organization and execution, the Pasha managed to reformulate the Egyptian army, making it a well-trained single unit that worked in complete unison, unlike the previous regiments, which relied upon personal strength and bravery above all else. The establishment of this modern corps then provided the stepping-stones towards a more progressive society, although not through direct intention, but rather through adaptation.

The meticulous attention placed upon creating a seemingly solid, organized, and infallible military as well as the stringent methods incurred in order to transform the Egyptian peasant into the ultimate warrior, transgressed the military realm and influenced a number of bureaucratic, economic, and social innovations. Textual devices including the census, roll-call, and training manual led to the increasing use of standardized state documents, i.e. inventories, that not only increased the efficiency in documenting material goods and funds, but also Egyptian citizenry.

Additionally, the need to educate and maintain the health of the soldier led to the founding of schools and hospitals throughout Egypt, while the necessity to provide clothing and arms for the drastically increased number of soldier allowed for the first industrialized factories and mass processing. While all this may seem to speak of modernization, Fahmy maintains that most of these innovations were simply the by-products of the militaristic administrative system being imposed upon the civilian bureaucracy. To accommodate his army, Mehmed Ali adapted his society.

The seemingly structured and impenetrable military, administration, and society of the Pasha were although plagued with problems. The primordial air imposed upon the governor by many French and British contemporary accounts show the prevalence of the living myth. But reality reveals instead that Mehmed Ali, achieved nothing without constant negotiation and reformulation. It is apparent that, far from delivering his subjects from foreign oppression, the Pasha instead structured a potentially modern, yet militaristically governed state, invoking the same overly disciplined and often times dehumanizing methods of control that were exerted upon the army, on his populace as well.

Nowhere within the text is Fahmy supportive of the idea of nationalism as having developed throughout this time. If nothing more, the forced conscription and constant surveillance of both the Pasha’s soldiers and common populace only heightened tensions between the ruler and the governed, and by no means was any individual of either group convinced of being part of a homogenized nation. It was therefore not by nationalism that Mehmed Ali was able to lay the foundation of the modern Egyptian state, but rather through manipulation and monopolization, both of which were methods invoked in order to help realize his ultimate goal of securing a hold on Egypt for his family. His personalistic ambitions, which speak harshly against his legacy as the father of nationalism and modernization, were albeit not as not without the constant interference of resistance and rebellion, which stood, perhaps, as the only socially unifying factor of this time.

Copyright Lilith Eden 2011. All Rights Reserved.