Memory and Amnesia

Traumatic memories can debilitate people. They reawaken sensations of past pain, and can cause actual physical pain. Powerful traumatic memories can invade one’s daily activities and impair one’s quality of life. Historically modern medicine has treated any disability to the fullest extent so that the patient has the highest quality of life possible. We should apply this approach to physical ailments, as well as mental ones. In an age where only will power and money can alter one’s appearance, why should we not alter the painfulness of our memories? Even though cosmetic surgery involves less imagination than memory modification, new medical techniques are making it possible to alter certain aspects of emotionally charged memories.

A study done by Professor Roger Pitman of Harvard Medical School on victims of post traumatic stress disorder showed that

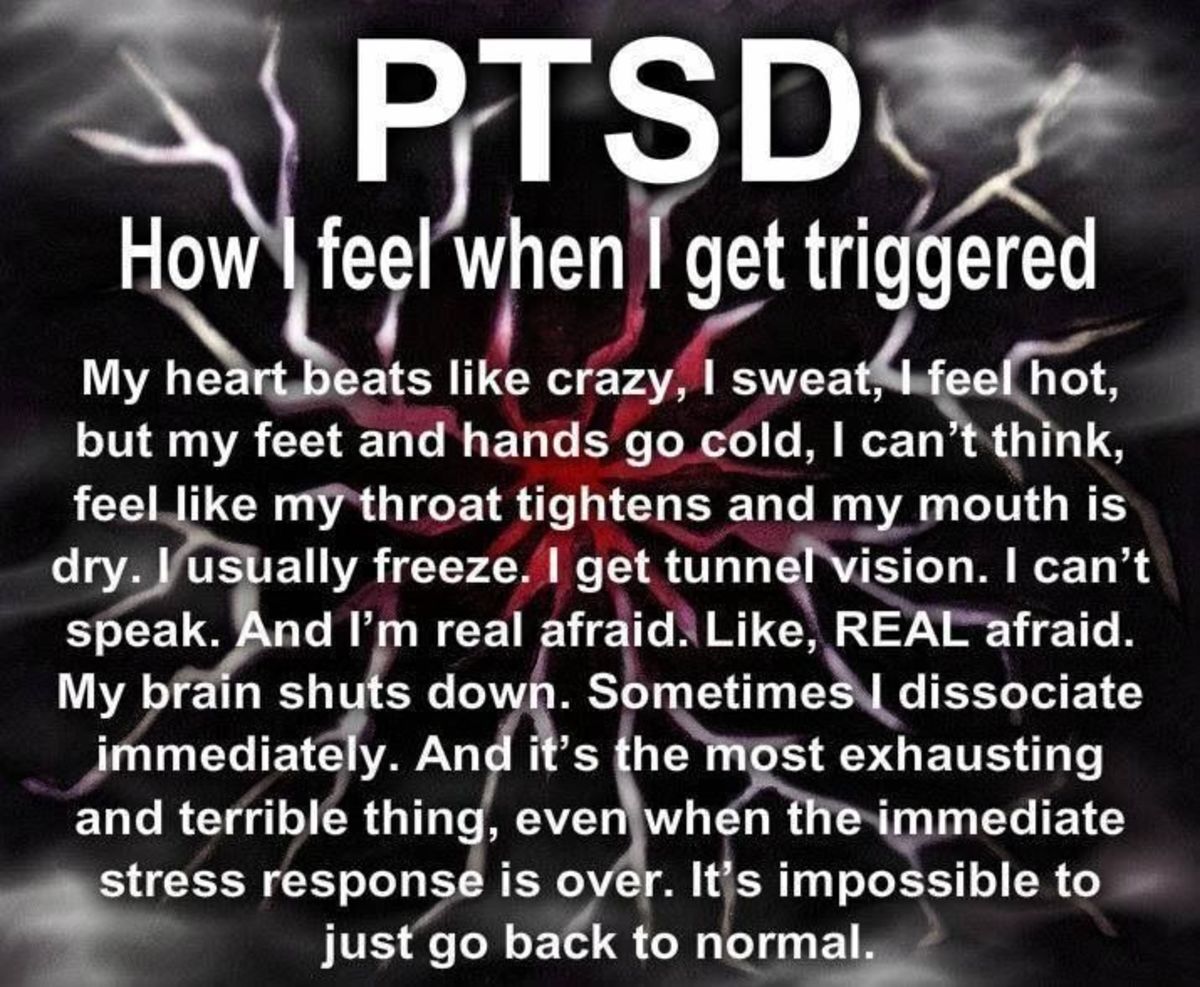

“When stress hormones like adrenaline and norepinephrine are elevated, new memories are consolidated more firmly, which is what makes the recollection of emotionally charged events so vivid, so tenacious, so strong. If these memories are especially bad, they take hold most relentlessly, and a result can be the debilitating flashbacks of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Henig 3

A recent New York Times article entitled “Quest to Forget” explains the process of giving certain stress hormone interfering drugs such as propranol to trauma victims directly after the time of the trauma. These kinds of drugs make it possible to prevent the most painful parts of a memory from taking hold. Propranol does not affect non-emotional memories and can not make the memory more difficult to recall. However it can possibly stop traumatic memories from becoming the kind of debilitating flashback memories that post traumatic stress victims suffer from.

For scientists who conduct research on post traumatic stress victims, memories of combat, rape, or terrorism, are worth forgetting. Eric Kandel, a professor of psychiatry and physiology at Columbia University even argues we must help soldiers back from war get through the mental injury that may have the may have sustained,

''Going through difficult experiences is what life is all about; it's not all honey and roses,'' he argues, ''But some experiences are different. When society asks a soldier to go through battle to protect our country, for instance, then society has a responsibility to help that soldier get through the aftermath of having seen the horrors of war.''

Henig 6

Kandel makes an important point, if we ask these soldiers to risk their lives to protect ours, isn’t it our responsibility to provide them with all modern medicine can provide to help them heal from the experience? And yet some scientists and mental health advocates would argue that in this case, we should let nature take its course rather than try to immediately alleviate someone’s suffering.

The new science of “therapeutic forgetting” raises some of the same questions as does Michael Gondry’s film “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” in which two ex-lovers try to erase their memories of each other. The film asks the question, if we have the power to erase painful memories, should we? Even though Propranol can not actually erase memories it seems to lead down a path where possibilities like that exist. In “Quest to Forget” Robin Marantz Henig quotes a study done by the President's Council on Bioethics entitled “''Beyond Therapy: Biotechnology and the Pursuit of Happiness”. The study concluded that retaining the strong emotions that come with powerful memories might have some value.

Changing the content of our memories or altering their emotional tonalities, however desirable to alleviate guilty or painful consciousness, could subtly reshape who we are,'' the council wrote in ''Beyond Therapy.'' ''Distress, anxiety and sorrow [are] appropriate reflections of the fragility of human life.'' If scientists found a drug that could dissociate our personal histories from our recollections of our histories, this could ''jeopardize . . . our ability to confront, responsibly and with dignity, the imperfections and limits of our lives and those of others.''

Henig 10

While memories do make us who we are and the teach us the “the ability to confront the imperfections and limits of our lives and those of others” the most traumatic memories can become inhibiting. If we do not try to treat them we sentence their sufferers to a life filled with fear and emotional pain. Take for instance patients of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder whose symptoms include borderline personality disorder, social and emotional handicaps, sleepproblems, irritability, anger, poor concentration, blackouts, and memory loss. Why should someone suffer all of those difficulties if there a possibility of minimizing some of them? The disadvantages far outweigh the benefits in the propranolol vs. memory debate. Professor Roger Pitman in his work for the National Institute of Mental Health argues that even if there’s only a twenty percent chance of reducing the effects of post traumatic stress disorder with propranolol it’s worth it. “Think of the amount of human suffering we could avoid”, he says.

However, a completely different moral dilemma arises when someone has actually lost their memory and believes they live in another place and time. Rose R. in Dr Oliver Sacks’s memoir Awakenings has this issue. Miss R., one of the Post-Encephalitic Parkinsonism patients that Dr. Sacks studies at Mt. Carmel Chronic Hospital, contracted sleeping sickness at age twenty-one and never recovered from her initial bout in 1926. Stuck in a trance-like state for three or four years, she eventually deteriorated physically until the left side of her body froze up and she stared having trouble walking, and exhibited other signs of Parkinsonism. When Dr. Sacks first meets her she suffers from a near constant state of oculogyric crisis, the inability to walk or talk, and completely dependence on full time nursing care.

“She sat upright and motionless in her wheelchair, with little or no spontaneous movement for hours on end. There was no spontaneous blinking, and her eyes stared straight ahead, seemingly indifferent to her environment but completely absorbed...Her face was completely masked and expressionless…Miss R. could not rise to her feet unaided…”

Sacks 77.

Dr. Sacks, continuing on his trial of the drug L-DOPA in post-encephalitic Parkinsonism patients, started her on L-DOPA in June of 1969 to spectacular effect.

Miss R. began to show immediate signs of improvement when first administered the drug. Through her course on L-DOPA Miss R. yo-yoed from tremendously good effects to extremely bad ones. Initially her condition seemed to improve greatly on L-DOPA with the ability to walk, talk, and rely on herself for more. However she soon she started to exhibit some negative signs such as depression, rigidity, and ticcing. She eventually hit some intense difficulties and Dr. Sacks felt compelled to lower the dose of L-DOPA. But the most fascinating part about Miss R’s case is her state during the initial administration of L-DOPA, when she was doing better than she had even been since 1926. During this time period she seemed to think that she was still living in 1926. While riding on the wave of benefits from L-DOPA she would sing songs from 1926 and make reference to ‘current’ figures from that time period. At the same time Miss R tried to avoid anything that would make her realize that she was deluded. Dr Sacks describes her condition in the following passage:

“Her memory is uncanny considering she is speaking of so long ago…She is completely engrossed in her memories of the twenties, and is doing her best not to notice anything later. I suppose one calls this “forced reminiscence” or “incontinent nostalgia”. But I also have a feeling that she feels her “past” as present, and that, perhaps it has never felt “past” for her. Is it possible that Miss R. has never, in fact, moved on from the ‘past’? Could she still be ‘in’ 1926, forty-three years later?

Sacks 83

For Miss R. her memories are what define her character and humanness, they are all she has left. Her identity completely intertwines itself with her memories of the twenties in which she describes leaving school, traveling in aeroplanes (new technology in these days) to cities around the country, and going to parties from which she “rolled home drunk”.

Dr Sacks comes up with a hypothesis as to why Miss .R might cling so strongly to the memories of her past. He thinks it’s possible that she has no idea of any other way to live. It was as if she was dropped through a vacuum from her twenties to her sixties, awakening (with the help of L-DOPA), to find that she just turned sixty-four. He explains this phenomenon as a “forced nostalgia”,

“…In her ‘nostalgic’ state she knew perfectly well that it was 1969 and that she was sixty-four years old, but felt that it was 1926 and that the was twenty-one; she adds that she can’t really imagine what it’s like being older than twenty-one, because she has never really experienced it. For most of the time however, there is ‘nothing, absolutely nothing, no thoughts at all’ in her head, as if she is forced to block off an intolerable and insoluble anachronism…”

Sacks 87

Whatever her mental state at the time, Dr. Sacks decides that since she seems happier and more active than she ever he should allow her to stay in 1926 and not try to shake her out of her fantasy.

Memories define our character and our humanness without them we are as lost as Miss R. before L-DOPA- emotionless, senseless, uncompassionate, and unknowing. However, some negative memories hold on so strongly that they can take over our lives and stop us from living them to the fullest. Even though memories make us who we are, and give us the ability to feel compassion, some memories, such as those harbored by combat veterans and trauma victims, are not worth remembering.

Works Cited

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Dir. Michel Gondry. Perf. Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet. Universal, 2004. DVD.

Henig, Robin M. "The Quest to Forget." The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. 4 Apr. 2004. Web. 18 Oct. 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/04/magazine/the-quest-to-forget.html>.

Sacks, Oliver W. Awakenings. New York: Vintage, 1999. Print.