My Creationist Unschooling Principles (Real Life Examples)

What Is Not Covered in This Article

The aim of this article is simply to give you an idea of how our family goes about educating ourselves, so you can better decide how you want to conduct your own family's education. I do not discuss the pros and cons of homeschooling. I do not discuss the way other people do things. I do not discuss the public or private schools.

I am a Bible-believing, God-fearing mother, and this shows in my philosophy. However, my family and I do not shut ourselves up away from the world. We have chosen to homeschool for practical and relationship reasons, not because of fear. I feel qualified to offer our experiences on the grounds that I was successfully home schooled K-12, have taught various subjects to a variety of children and adults since I was 16, and have always homeschooled my two children. My oldest is 17 as of November 2019.

Why I Wrote This

It is my hope that reading these snippets of our lives may inspire others who have been uncertain whether or not homeschooling is a good choice for them. I hope it will cause them to commit to homeschooling their children, and to be able to work out exactly what they want, and why. There are no hard and fast rules regarding the appropriate way to homeschool. Every family's needs are different, and homeschooling lends itself to most of these situations.

Don't be afraid to experiment, and don't be afraid to listen to and consider what your children need and want. The more individual interests you can work into your plan, the better off everyone will be. All of you will even have more energy for subjects you don't particularly want to do at all!

Fun and Games, yet Serious

My Homeschooling Philosophy in 7 Points

I wanted to homeschool my children since before I first conceived. I spent years considering and honing my philosophy.

Here is the result, after several years of practice.

I believe that:

- Children are not miniature adults, but they should be trained to become productive adults. This means practicing adult skills such as cooking, mechanics, woodworking, business practices, gracious communication methods, and courtesy. The object of any formal education is to teach a child to learn. If this is accomplished, he will be able to continue educating himself throughout his life.

- Children are capable of deep thoughts, and are capable of conversing with adults on intricate topics. Examples may be politics, philosophy, religion, history, human nature and behavior, and science. Even young children can usually be taught to think (somewhat) logically, and to express thoughts clearly.

- Learning cannot be effectively put into a schedule or confined to any set of rules. Traditional classroom teaching, while sometimes necessary, is not as effective as one-on-one instruction, and becomes evil when it causes deterioration of a child's Creator-endowed creativity and natural curiosity. When it serves to cause a child's soul to conform instead if to transform--when it ignores real life interests or crushes his spirit--it has become evil.

- Books, the internet, and other "education" aids are just that--aids. They are tools with which to make a concept more clear, to refine or recondition thought processes, and to introduce wider thoughts. They are never an end in themselves, and cannot be counted on to provide the necessary skills to make a child successful in life. Spontaneous conversation, the opportunity to work with one's hands, and a wide range of experiences and situations are essential to a well-rounded education. The opportunity to do real-life things such as: tear apart a motor, build a box kite or knick knack shelf, train a dog or horse, paint a mural, or wade in a pond full of scum and tadpoles, is essential to building confidence in young minds.

- If children will be expected to deal with a variety of people as adults, there is no better time to teach them than now. The best way to go about this is to deal with a variety of people in our daily lives, and let them observe, or be involved as is appropriate and relatively safe for them. They should be encouraged to learn to appreciate people of varying mindsets and from different walks of life, and can best do this by being shown how. They will learn skills such as apologizing in the same manner.

- Whatever I do, I can expect my children to do the same--especially gleaning from me any unsuitable behavior, words, or attitudes. More is caught than is taught. I therefore must be on my best behavior, and strive to make each thought worthy of the Scripture verse Philippians 4:8, which in essence means, Helpful to All Concerned.

- More than all this, I must model the Creator for my children, inviting Him to be the center of our home, and the standard by which we think and live. I must allow Him to speak and breathe through me. Therefore, if He says it, it goes. If He does it, it's the mark to hit. If He stays away from it, we run for all we're worth! We have chosen to take as our foundation the King James Version of Scripture (though others may be occasionally helpful), and are learning to wait patiently on the Word Himself to explain the hard parts. We can ignore the negative things negative people make Him out to be, and get to know Him for ourselves through His influence in every detail of our lives.

Philippians 4:8, KJV

Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.

Mind, Body, and Soul

"Doing" School vs. Learning

The following observations were first written in January 2009, and have been updated as needed:

By reading my Philosophy, you can readily see that we don't really "do" school. We arrange life so that we are constantly learning, whether it is intentional or haphazard. We surround ourselves with challenges, new subjects, and things to wonder about, and give each other a chance to share our discoveries. In this light, learning is not something that we do while we're waiting for life to happen--it is life.

I used to have people come up to me frequently to ask whether I'd started Billy in any workbooks yet, or what method I was using to teach him to read. The child was all of three years old when these questions began to be posed!

The answer, of course, was No--I was not using workbooks, and we used no "method" with our reading. Reading involves many types of processes and skills, and no one method covers them all, or provides a sound basis for understanding and applying what is read, even if the reading itself is fine. The same goes for almost any other subject.

Learning is a process, not an event.

Spontaneity in Learning

Learning is a process, not an event.

How My Children Learned to Work With Words

From the time my son was an infant, we sat down with books and we read, a few minutes here, a few there. (Billy was hyperactive.) I pointed out letters and words, we talked about pictures and colors and shapes and activities, and he absorbed, processing the information naturally and erratically, as most of us do.

Even before he could read or use language to clearly communicate, I read to him some of whatever I happened to be enjoying or studying myself. He heard poetry, history texts, novels, the Bible, how-to's, math problems related to construction, and cookbooks. He began to feel how the English language is formed long before he could speak or explain it.

He was also challenged to develop an interest in many subjects.

For the most part, I let him set his own pace, and pushed only when I knew he was deliberately stalling--which he tends to do with every new subject or concept. In this way, he advanced to spelling, penmanship, punctuation, and recognition of sentences and phrases, in approximately that order. Between his 4th and 7th years, we did quite a bit of dictation and copy-work, as well as reading aloud (both him to me and me to him).

My daughter was introduced to language in a similar fashion, except that she hit a snag which Billy didn't. She has dyslexic tendencies, with which I am very familiar, as it runs in my family. Secondly, she is a perfectionist. She claimed that she couldn't read until she was nearly eight, on account that she didn't know all the words she came across. It took her a while to accept the fact that this is true for everybody, and doesn't matter as long as she keeps expanding her vocabulary.

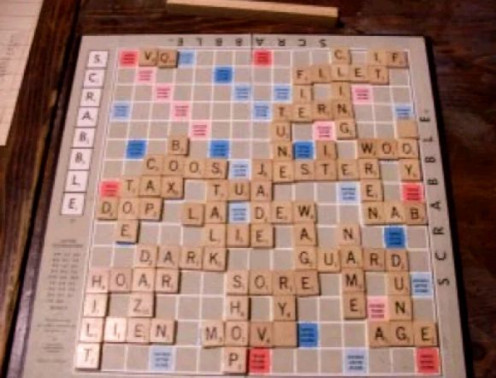

Both of my children enjoy reading, and read on a wide range of topics. They are not afraid to tackle tough topics or high-level writing. (If they pick something they're not ready for, the worst that happens is that they decide to try again later, and put the difficult book back on the shelf for a while.) They love words, and enjoy games like Scrabble, as well as plays on words (puns, connecting meanings in unusual ways, etc.). They also are constantly asking me about the origins of certain words, and are delighted to learn new foreign words, be they Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Chinese, or Spanish. They are learning to use information and word helps such as dictionaries (both standard and online), encyclopedias, and a Bible concordance.

They have both struggled with reading comprehension, and we have occasionally used drills or worksheets to increase their skills. Still, these have proven to be an exception to the rule of organic education.

Their favorite books while younger were invariably science related, and they both knew much about animals, minerals, astronomy, and building and fixing things. On our homestead, these are everyday topics.

Billy's First Scrabble Game

Mathematics

We have gone at mathematics in a similar fashion.

First, we counted--coins, crackers, apple slices, numbers on a tape measure. After a while, we progressed to counting without objects (abstractly), and just before Billy turned six, he could count to 100 without mistakes or major hesitations. Is this better than average? No. But the point is, he learned to count because he needed to--not because he had to. He wanted to be able to use his tape measure accurately to cut boards for birdhouses and other projects. He began to understand fractions because he needed to know how wrenches are labeled, and what the other lines on a tape measure mean.

Both my children took a long time to learn how a dollar breaks down into percents, and why, but once they were given the right to manage their own bits of money, and began to be paid for doing odd jobs for other people, this skill progressed fairly well.

Billy first acquiesced to simple mathematics (adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing), because of an agreement my husband made with him. He pays him for work well done, and docks him for work done shoddily. Everyone else Billy works for does the same. Billy has also had to pay for things he deliberately broke, and was sorrowed to see the coins in his bank dwindling. When he made the connection, he sat down and dumped out the remaining coins to answer the question, "How much do I have left? Is it enough for more caps for my cap gun?" Later, he progressed to calculating for engine parts and tools, and eventually started a small-engine repair business. His business and math skills are both fairly professional now.

Since the early grades, both children have struggled somewhat with math. Particularly for Tyger, it simply does not make sense. She'd rather care for our sheep or create artwork than do Algebra any day! Yet she perseveres, because that is part of life as well.

When Billy was 12, he decided he wanted to be a scientist of some sort. He immediately set his mind to learn all the math he could, so that he's ready for whatever comes next. He also worked regularly in woodworking, mechanics, and machining, and learned not to be so stubborn when he was faced with new concepts or setbacks. He gritted his teeth, got up to speed, and is stayed about a grade ahead of where "his class" is most of the time.

It has taken some experimentation to figure out what combination of workbooks, textbooks, tutoring, and online tutorials and lectures was right for him. Adjustments continue to be needed, but helping him find an incentive has been the biggest victory.

My daughter, 13 in November 2019, loves workbooks. She likes racing through the pages, telling me, "I got this much done!" She also needs the freedom to be able to skip ahead, try something above her level, then fall back and practice something more familiar. So she is always doing a combination of things she's learned to this point, solidifying how the different concepts dovetail. She still likes to be allowed to use objects (or fingers) with which to count, and has thus far weaned herself off this "crutch" in the easier stages while retaining it in less familiar territory. She is serious enough about so many things that I haven't stressed math a lot in the way of a ladder to climb, and she still has managed to keep a somewhat playful attitude toward it. I hope to be able to continue this.

She is slowly working through pre-Algebra, and is finding it both stressful and rewarding. She continues to supplement with easier material, and takes frequent breaks to color or draw, or to get active outdoors. I often tell her, "I don't care how it gets done, just so that it does!"

Fun With Money

Social Studies

From working with coins, Billy began to build a concept of history and government (combined with our emphasis on an upcoming presidential election). I explained to him who and what was on each United States coin, and what the symbols meant. I told him a few stories about Presidents Lincoln and Washington, to illustrate why they were considered such great men.

After a while, he could readily name them, and sometimes tell a story about them. By and by, he'll know a lot more, and will be able to make up his own mind about their characters. Of course, as a small child, he was still more interested in which coin was bigger than which, and how shiny they were, or whether they were older than his daddy.

In his pre-teen years, we took full advantage of what we call our "Picture Wall". This is a small wall in our dining room which is reserved for posting pictures having to do with anything we are currently studying. This might mean pictures of statesmen and other leaders (foreign and U.S.), scientists, philosophers, or authors; inventions and things to make (including foods); animals, plants, or scenes from nature; Bible verses and poetry; and special artwork. We change out the pictures whenever we feel we have gotten from them whatever we needed, and are ready to move on.

Our Picture Wall

Further Social Studies Resources

We also use songs in our studies, making a point of learning historical details from songs such as Johnny Horton's "Bismarck" (taken with a grain of salt because of unavoidable biases, naturally).

Sometimes we use books. When Billy was small, I came across a thin, but jam-packed little book called My America, which explains in nice pictures and photos the main points about the "Pilgrim's" coming to America, what the Constitution is, how to respect the American Flag, and how our Nation's Fathers designed our Government to work. Did Billy "get" it all the first time through? No, nor the second. But he found it interesting, and he got something out of it. It paved the way for a deeper understanding of democracy, integrity, and political and religious freedoms.

We also use novels, picture books, histories, and encyclopedias. When Billy was 13 and Tiger was 9, we read Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which I thought would probably be above the kids' level. But they loved it! They got a different view of France and the Middle Ages, which can be built upon as long as they live.

Likewise, we use videos and movies. The point in a movie isn't whether every detail is accurate (because most books aren't either). The point is whether it sparks an interest in a time, place, or event, or leads to a connection between my family and other people. In that sense, movies like "Braveheart", "The 300 [Spartans]", "Les Miserables", "Gods and Generals" (American Civil War), "Dead Poet's Society" (which has the theme of learning to think for yourself), and even Disney's portrayal of Pocahontas are valuable. We also sometimes enjoy documentaries, and Billy, particularly, is always looking up something on Youtube about how a thing is made, or who did what, or what sorts of weapons were used during WWII, or how to build a model of Henry Ford's first engine.

Billy has an ongoing interest in the U.S. presidents, and has memorized facts about many of them. He was given a jigsaw puzzle featuring them, and has put it together several times. We pay most attention to the characters and intentions of leaders in an effort to absorb what is really important, rather than getting stuck in the details of what they did or didn't accomplish. After all, politics are complicated, and full of unsavory facts, no matter what.

We regularly discuss current events, motives, morals, and consequences. We do this while we wash dishes, while we take breaks at work, while we clean, and while we live. This is what I meant in my Philosophy about schedules--I can't cram learning into a schedule, because our minds are always at work.

We discuss the ways in which other people live, how they think, what their beliefs seem to be, and how they dress and what they eat. We use a wall map or Google Earth to illustrate where they live. I'm not quite sure what my children's concepts are of Earth, or China, or Central America. The important thing is that they are developing such concepts; we can iron out the wrinkles later, and experience will continue to teach them the facts.

Johnny Horton, "The Bismarck"

Social Studies Goes Outdoors

What About Science?

Science is an every-day thing, just like eating and working. It varies with the seasons, and with what work is most necessary.

Science is finding out the many health benefits of a properly picked dandelion, and originating suitable recipes for the same. It is understanding why we don't drink municipal tap water.

It is understanding the idea behind a homeopathic remedy, or why certain people's electromagnetic fields influence electronics more readily than others.

It is catching tadpoles or beetles, and keeping salamanders in a terrarium, and making sow bugs comfortable in confinement to see how they live. It is watching a cicada emerge from its long underground life, and observing the transformation of its body from pale green and lavender to an olive green, then to an aged brown. It is holding a flower from which a wounded butterfly may sip. It is knowing that this butterfly is a Monarch, and how to tell it and its caterpillar apart from other species.

Science is knowing why the sun rises and sets (and being able to explain and illustrate this with your own movements). It is knowing what happens to gunpowder when the primer of a cartridge is struck. It is understanding why yeast makes wheat bread rise, and why we need baking soda for some other types of baking.

It is finding an unusual fungus, and determining why it only develops fruiting bodies on a single log or patch of soil.

It is surmising that there is gold in the private water well, and developing an automatic panning system to capture the particles.

Most of all, science is practical. It is understanding why we soak our beans in water and whey before we cook them, and why hard cheeses taste better for being aged. It is watching the conjunction of two planets and the moon, and recognizing that the Creator orchestrated this show . . . recognizing that He is a Father on whom we can lean. It is He who wrote the Laws of the Universe, and it is He who upholds the Creation with the Word of His power. Science is understanding that He is an orderly God, and that all which is not essentially orderly does not proceed from Him. It is finding the patterns shown throughout His Word, and understanding that all true knowledge and wisdom come from Him, and are a part of His being.

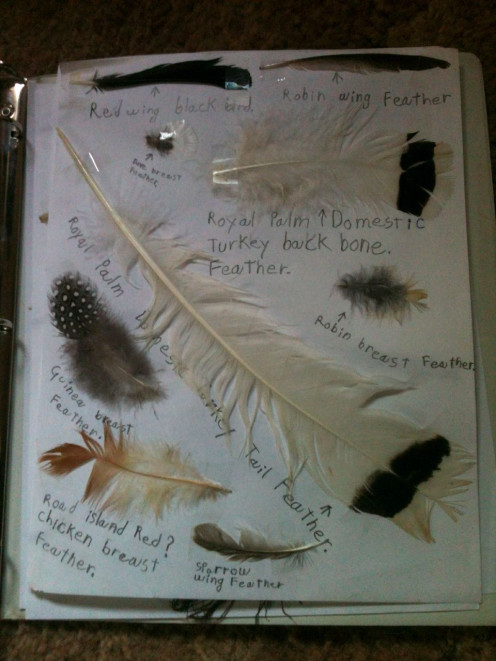

To explore these concepts, we use texts, videos, and other aids, but rely primarily on observation, as true scientists have always done. We are fortunate to live on a rural acreage where opportunities abound. We keep various kinds of poultry and livestock, and prefer to care for our yard organically so that insects and birds are quite at home. We make good use of animal identification sources, and log the animals we see, taking photographs when possible.

We take excursions to ponds or wet spots. We go tramping in the snow. We work and walk in all kinds of conditions and at varying times of day, and never lack for things to do. We welcome owls and game birds and songbirds; deer and mice and rabbits and skunks. We set up welcoming stations for bees and other pollinators, and plant flowers and grasses and trees. We listen to the coyotes singing of an evening. We stargaze when we check pregnant ewes in the wee hours of the morning.

During lambing season, we attend births, cuddle babies and soothe mothers, shelter and feed any orphans, and adopt the rejected. We doctor unwell or injured animals.

We study building design, and watch weather patterns before deciding where and how to build a new barn or shed.

We fix our own vehicles, process our own meat, make our own cheeses, and grow and preserve our own vegetables.

Billy, particularly, has learned much valuable chemistry as he develops his philosophy of engine repair and improvement. He listens intently to the stories and experiences of his elders, and learns from these tales certain things he must not do--especially involving anything that may go BANG!

We have no opportunities for engaging in biology labs such as dissecting frogs. But there is no need when the children already know how to butcher a lamb or chicken, and have observed one-celled creatures of their own accord. They have frankly done quite a bit of lab-type exploration on their own, using mice, insects, and birds. (Especially specimens which the cats killed and brought indoors!)

Teaching from a text on the subjects of sexual reproduction and behavior is fairly redundant when Tyger has long been involved in raising chickens and ducks, and regularly deals with the frustrations of testosterone-laden rams or protective mother sheep. She and Billy watch the habits of songbirds and dragonflies, of Jack rabbits and roosters and wild turkeys, and their peers.

Teaching about the habits of wildlife and especially of predators is equally redundant. They kids know first-hand about all the wildlife which may destroy pets or livestock, and have had experience dealing with many such predators. They know about the system a coyote employs to bring down a baby calf. They know about the habits and ranges of mountain lions. They have watched chicken hawks raid the nests of ring-neck pheasants, and seen the silent-flying great horned owls nab domestic chicks. They have learned the tracks of skunks and raccoons, and have learned the signs of a potentially rabid pest. They have learned to know the differences among the various kinds of dung they may encounter along the trails and paths, or among the trees of the windbreak.

Finally, the children both assess the sometimes unlikely things they see on movies or that they may hear from peers, and have a very good idea of what is possible, and what is just a story.

Science Is . . . Engine Repair and Maintenance

Science Is . . . Lamb-Sitting

Science Is . . .Building and Repair

Science Is . . . Nature, Wildlife, and Cooking

Physical Education

For us, there has been no need to deliberately focus on the building of strength or physical prowess. There is always some kind of physical work that needs doing.

Hauling and stacking bales of straw or alfalfa, or preparing a cement pad for a building is always good exercise. Putting on metal roofs, building post frame sheds, digging gardens, cleaning out a lambing barn or chicken house, and hauling water are constant realities.

For fun, both children ride bicycles, or climb ropes (hand over hand, mind you, and you can't use your feet, you cheater!).

They mow lawns and change tires. They haul and split firewood. They round up sheep. In a thousand ways they make constant use of their bodies.

So the secret of physical education is: work! Work at great things; work at small things. But move. Bend, twist, squat and leap. Scrub the floor. Paint a wall. Climb a ladder. Repair a window. Learn yoga. Learn nutrition. Take supplements. Eat liver. Plant tomatoes. Dig potatoes. Prune a fruit tree. Be adventurous.

Physical Exertion

Education vs. Learning

We don't "do" school because that's not how most people naturally learn. Maybe you can quote your times tables, or rattle off every (outdated) country in Africa, or list all the main leaders of your country. Wonderful. These are valuable things in themselves. But what do you like doing and remembering?

For my part, I'll continue to help my children like learning so that when they're "out of school", they still won't act like it. Because I don't sit them down to do busy work . . . because we sorted clothes and silverware and firewood instead of pictures made for the purpose . . . because we live as we learn, my children have learned a lot. They're on their way to being prepared for most anything they wish to undertake--mentally, if not immediately. Working with their hands, as well as their brains, has given them confidence and quick-acting minds. It's given them a will to succeed, and to make their own success.

Skills can be learned as they experience life. For those with determination, patience, and the will to innovate, there is always a way through.

Eight hours a day in a typical classroom can't provide the mindset necessary to finding this way. But a life lived deliberately, one day at a time, can.

I Went to the Woods . . .

. . . to Live Deliberately.

I have never let my schooling interfere with my education.

© 2019 Joilene Rasmussen