- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Napoleon: The Italian Campaign- The Closing Stages

A Quick Recap

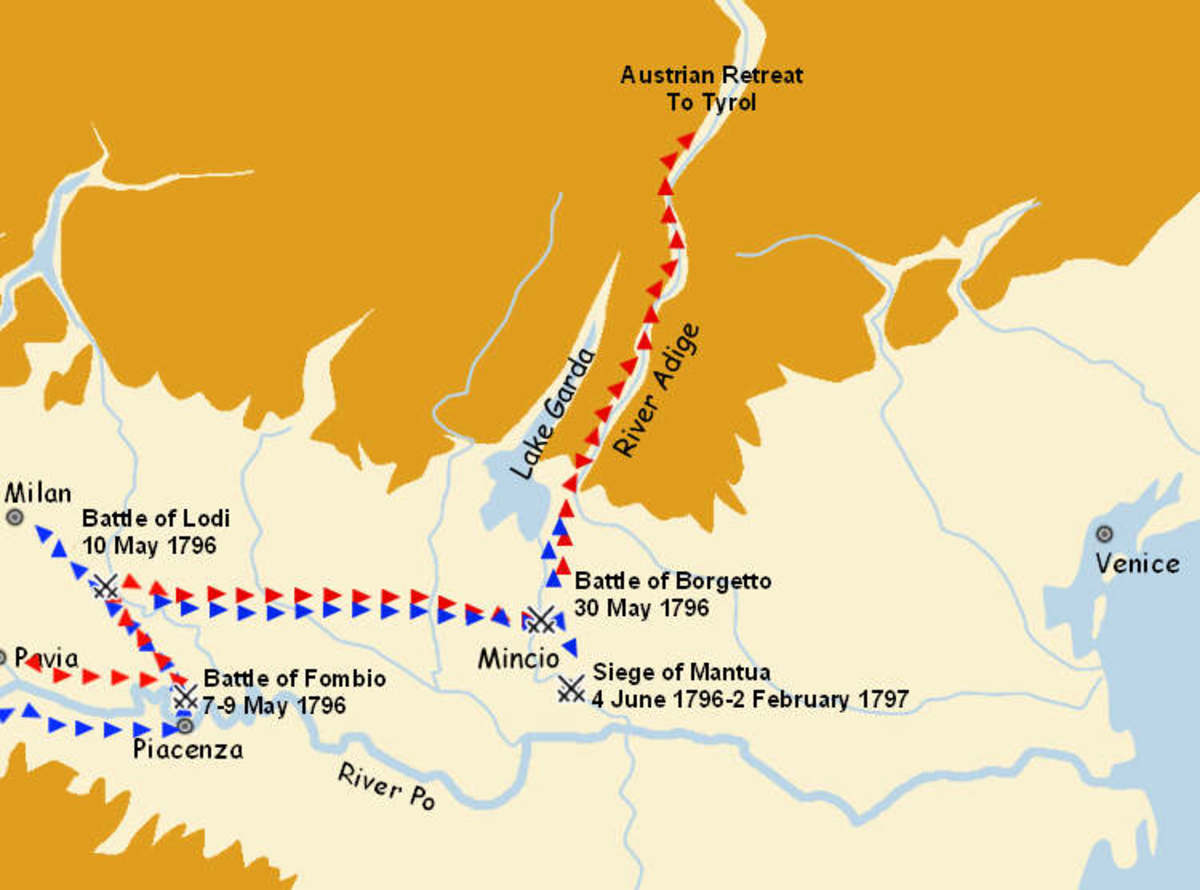

Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Italy in the name of the French Republic has gone swimmingly so far. After sweeping across the mountains of the north, he then proceeded to cross the Po Plains, advancing almost as quickly as the Austrians were retreating. In the process, the French have captured two iconic cities Milan and Verona. Bonaparte himself launched a scarcely believable invasion of the Papal States, and only the calls for peace from a desperate Pope prevented him from advancing any further.

Further north, one of Napoleon’s generals, Jean Serurier having won many battles, now finds himself before the seemingly unbreakable walls of Mantua. Despite, having to endure 12,000 exploding shells in under a month, the dogged Austrian defenders are refusing to yield, leaving Serurier and his force frustrated. Now, it seems that fortune is finally starting to smile on the Austrians; help is on the way.

The Battle of Lonato

Austria Fights Back

As July neared its end, a fresh, new Austrian army under the command of Field Marshal Wurmser marched towards the besieged city, hoping to provide relief for the increasingly desperate population. The army advanced in three columns, with Wurmser taking command of the central column himself, as they advanced confidently down the Adige Valley. The eastern column under General Szoboszio converged upon Verona, while the western column under General Quosdanovich headed down the Chiese Valley towards the city of Brescia, the idea being to threaten Napoleon’s complex lines of communication that ran back north towards Milan. To his surprise, Wurmser found that the road to Mantua was completely wide open, and took the opportunity to enter the city, much to the delight of the beleaguered natives, but something didn’t seem right, it all seemed too easy.

While Wurmser was marching through the streets of Mantua; Napoleon decided to swing his forces to the south of Lake Garda and engage Quosdanovich at Lonato, over the next forty eight hours, the Austrians were pushed back, losing control of Brescia, turning north east towards the Lake itself. Quosdanovich realised the implications of Bonaparte’s attack; he was gradually being cut off, and he needed to join up with Wurmser as soon as possible.

In early August, he once again engaged Napoleon at Lonato, but again the result wasn’t favourable. Furthermore, the failure to break through meant that Napoleon could turn about and pursue Wurmser’s column. It was only now, that Wurmser realised that he had been duped by Napoleon, into entering Mantua. Abandoning the city in haste, his column marched frantically to join up with Quosdanovich. On the 4th July, he found himself face to face with Napoleon’s army near the town at Castiglione, fearful of the reputation of the French columns; he formed his own in a defensive position just to the east of the town. Initially, at the start of the battle, he had the advantage, but still maintained a defensive position, as Napoleon ordered his men to carry out a series of attacks that would ultimately turn out to be a series of cleverly co-ordinated feints, to keep the Austrians in place until reinforcements arrived.

Eventually, Napoleon’s reinforcements arrived, turning the numerical disadvantage on its head, now he attacked for real, pushing the Austrians back towards the Mincio River. For Wurmser, it was a bitter blow, if he had been able to hold his position, then success would have still been in the realms of possibility, but now he found himself retreating back towards his homeland, allowing the French to re-establish the siege at Mantua.

Lake Garda

Napoleon's Enemy

Wurmser Tries Again

As August gave away to September, Wurmser was ordered to mount another attempt at lifting the siege at Mantua. This time, he decided to travel down the Brenta Valley and emerge onto the plains, just north of Vicenza. Once there, he joined up with another Austrian force, under the command of General Meszaros, the combined army would then strike at the French siege force from the east. Meanwhile, a force under General Davidovich was charged with protecting the area around Trento, but within a few days, the French smashed their way through his defensive line near Rovreto and punched another hole the following day near Calliano. Davidovich had no other option but to abandon Trento to the fate of the French.

Meanwhile, Napoleon was conducting his own offensive; his intention was to join forces with the French army of the Rhine, currently engaged with Austrian forces on the River Danube. He travelled up the Adige Valley, past Trento, before making a perilous crossing of the Alps, before finally joining up with the army of the Rhine to conduct an attack against the Austrian city of Innsbruck. However, his offensive was put on hold when he learnt of General Wurmser’s advance on Mantua. In an astonishing example of organisation and efficiency, he quickly redirected his army southwards, then eastwards to catch Wurmser.

Wurmser’s slow moving army was caught completely off guard and out of position by Napoleon’s army. In fact, he still had one division stuck in the mountains at Primolano, which gives you an idea of just how spread out his army was. Napoleon sent forth an advance guard to attack Quosdanovich at Primolano, and gained another victory. The day after, the 8th September, Napoleon embarked on another rapid march to attack Wurmser at Bassano and succeeded in splitting his army completely in two. Quosdanovich bade a hasty retreat eastwards towards Treviso, while Wurmser fled towards Vicenza.

Confident in achieving his goal of destroying Wurmser’s army, he pursued him all the way back towards Mantua, arriving outside the city walls with 12,000 men. Bonaparte and Wurmser fought a bloody pitched battle spanning forty eight hours, at its conclusion Wurmser was forced to retreat within the walls of Mantua itself.

The Battle of Arcole

Third Time Lucky?

General Wurmser, now trapped inside Mantua, was replaced as Commander in Chief by Field Marshal Alvinczy; overall he had 50,000 men at his disposal, just over half, belonging to Quosdanovich who were based at Friuli, right in the north east corner of the plains. The rest were based in Tyrol under Davidovich. By now, the toil of the campaign was beginning to take its toll, on even Napoleon’s men, as sickness and mounting casualties ravaged his army. In March, he had taken 37,000 into Italy, now he had just less than 28,000 men to throw against the Austrians.

Alvinczy commenced his campaign in early November by crossing the Paive River. Massena opted to pull back to Montebello via Vicenza in order to join up with Augereau, who was facing a huge numerical disadvantage. Despite, this state of affairs, Napoleon ordered Massena to attack the Austrians at the Brenta River, then he rejoined Augereau to launch another offensive at Citadella and Bassano, but this time their attacks proved fruitless, and they were forced to withdraw to San Martino, three miles east of Vicenza. Sensing an opportunity, Alvinczy advanced, liberating Vicenza on the 8th November and Montebello the next day.

The Austrians enjoyed further success when Davidovich was able to press his way down the Adige Valley. On the 2nd November, he was able to hold off a French attack at Lapis. Four days later, French general Vaubois was forced to fall back from Calliano and take refuge in Rivoli. From the French point of view, things were getting dangerous; the two Austrian armies were now very close to uniting. By the 11th November, they were just fifteen miles apart, indeed if Davidovich had sped up his advance down the Adige Valley, then he would have surely succeeded in joining up with his commander. But he proceeded a little too slowly, which gave Napoleon a valuable window of opportunity to strike against Alvinczy.

However, despite being handed the advantage, Napoleon came dangerously close to failure. On the 12th November, both Massena and Augereau attacked the Austrians at Caldiera and suffered a massive defeat. Even the usual upbeat Bonaparte was left sombre by the defeat and expressed his feelings in a letter sent to the French Directory. However, he was able to put misery to one side, for the sake of one more attack. Crucially the Austrians did have a chink in their armour; Alvinczy was moving westwards towards Verona, he had mountains to the right and the Adige Valley to the left. The only way he could retreat was down a narrow belt of dry ground at Villanova.

Napoleon launched his attack across the Adige Valley, near Ronco; the battle that ensued would take its name from the nearby village or Arcole. Bonaparte’s initial assault proved fruitless, and this allowed Alvinczy to pull most of his men out of a potential trap. However, two days later, the French claimed victory, forcing the Austrians to retreat eastwards.

For Napoleon it was a victory that couldn’t have come any sooner, because on the 17th November, Davidovich finally succeeded in forcing the French back towards Peschiera. If Davidovich had moved earlier, then Napoleon could well have found himself trapped between two armies. Napoleon took the forced decision to proceed westwards to assist Vaubois. For a while, in Davidovich’s case, there was a possibility that he might find himself trapped, but after fighting his way out of Castelnuovo, he managed to escape northwards. After Davidovich’s defeat, Alvinczy took the decision to retreat eastwards to recuperate and prepare himself and his army for perhaps the last chance to relieve the siege of Mantua.

The Adige Valley

Last Chance

Two months passed, allowing both sides to catch their breath, before Alvinczy launched another relief attempt. This time, he led the bulk of the Austrian army, 28,000 men down the Adige Valley, while another force under General Provera moved towards Verona and Legano from the east. This time there was no talk of combing forces, both Austrian forces were to operate independently, theoretically they should have both been strong enough to defeat the French on their respective fronts. Napoleon had less than 30,000 men, split into three divisions. Augereau covered Vicenza, Joubert and 10,000 men were based just north of Rivoli while Massena defended Verona.

The war had now moved into a second year, and sensing that it was now or never, the Austrians advanced on the 10th January, but met with instant problems, as one of Provera’s columns failed to capture Verona. However, on the 14th January his main force crossed the Adige and smashed its way through Augereau’s line, freeing him up to move towards Mantua. However, Provera’s success came to nought when Napoleon sensed that Alvinczy was the real danger and concentrated all of his forces on repulsing him, ordering them to station themselves at Rivoli. The little general himself, arrived just past midnight, with Massena and Rey arriving several hours later, this staggered arrival enabled Napoleon to throw reinforcements into battle whenever a crisis seemed likely.

He was further helped by the Austrian plan of attack, drawn up the previous day to annihilate Joubert’s isolated force. Alvinczy force attacked in three main columns, the idea was to attack the French along the Adige, as well as punch a hole in the centre, with an extra division deployed to try and outflank the French. Napoleon undid the complex plan, defeating each army column one after the other, forcing Alvinczy to call off the attack. The end result was catastrophic for the Austrians, more than 10,000 men lost, and a further 5000 captured by Joubert in the days that followed.

While Joubert pursued Alvinczy, Napoleon and Massena sped south to prevent Provera from relieving the siege. On the 16th January, Massena caught up with the Austrian general, who now found himself trapped between Massena’s army and Serurier’s force that still maintained their siege. With little alternative, Provera surrendered. The final defeat of Provera ended any chance of Mantua of being relieved, after waiting out another two weeks, Wurmser surrendered to Serurier at the beginning of February; finally the French had got their town.

Aftermath

With Mantua finally in French hands, Napoleon embarked on another invasion of the Papal States, moving down the east coast as far as Ancona, before the Pope once again called for peace. On the 19th February, Napoleon and the Pope agreed to the Treaty of Tolentino, the Papacy were forced to surrender Bologna, Ferrara and Ancona to the French.

Napoleon meanwhile embarked on a successful invasion of Austria, in fact he got so close to Vienna, that widespread panic gripped the city, with many people choosing to evacuate rather than witness the horror to come. Only an Armistice prevented Napoleon from advancing any further. Hostilities though did not cease until the 17th October 1797; the Treaty of Campo Fornio gave France Belgium and recognition of their rule over Lombardy and the rest of northern Italy. Peace prevailed, for now at least.

References

http://www.historynet.com/general-napoleon-bonapartes-italian-campaign.htm

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/campaign_napoleon_italy_1796.html#1

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/people_napoleon.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon_Bonaparte

Boycott-Brown, Martin,The Road to Rivoli, Cassell & Co, 2001

Chandler, D,The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillan, 1966

Dwyer, P, Napoleon- The Path to Power 1769-1799, Bloomsbury Books, 2008

Fiebeger, G. J,The Campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte of 1796–1797, US Military Academy Printing Office, 1911

Foreman, L & Phillips, E, Napoleon’s Lost Fleet, Discovery Books, 1999

Grant, R.G, Battle, Dorling Kindersley, 2010

Rothenberg, Gunther, The Napoleonic Wars, Cassell, 1999