The Significance of American Borders as Barriers and Passageways

Which is more significant to American history - Border Breach or Border Enforcement?

The nineteenth century saw the creation of physical borders in North America between what became the United States, Mexico, and Canada. Legal immigration, and subsequent enforcement of its borders, in the United States was successful depending on the definition of success. Legal immigrants from the late nineteenth century to modern America experience prejudice, discrimination, exclusion, and exploitation even after going through the proper channels to becoming a citizen. However, to say that enforcement of borders was more significant than their breach is inaccurate. Border enforcement tells only one side of the complex saga in which geographical features such as international borders became a question of belonging and power rather than one of simple land ownership. Native Americans who breached the Canadian/American border helped to establish its physicality. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Mexico and the United States benefited culturally and economically from those that contravened the U.S./Mexican border illegally to seek better opportunities for themselves. Borders in America serve as both passageway and barrier with immigration being paramount to its creation, sustainability, and existence as detailed in Metis and the Medicine Line, “Three Western Places,” Impossible Subjects, and This Love is Not for Cowards. Native Americans, immigrants, foreign nations, and Americans alike all played crucial roles in the enforcement and breach of borders since the nineteenth century in dividing and traversing not only land, but governments, cultures, and economies to create definitive modern nations.

The Metis, Fur Trade, and the 49th Parallel

The story of the creation, enforcement, and breach of the Canadian-American border unfolded for America in its Plains region affecting the Metis people. Metis people were migratory buffalo hunters of mixed indigenous and European heritage living along the forty-ninth parallel who befuddled the governments of the United States and Canada as to how to classify their race and nationality and which nation was just in their exploitation and exclusion.[1] Nineteenth century categorizations of race did not allow individuals to select categories beyond Indian and white. Mixed-heritage Metis proved problematic as they were neither Indian nor white but both – allowing Canadian and American governments to use race classification in the most beneficial manner to politics without fixed racial criteria.[2] Metis experience as nomadic tribespeople, along with their mixed cultural heritage, afforded them a foothold in both Canada and America and made them perfect subjects of exploitation for the creation of an official divisional border.

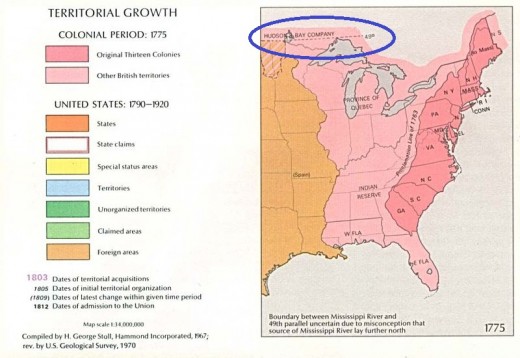

Before the physical survey of the forty-ninth parallel in 1873, Metis travel across the U.S.-Canadian border provided broader economic opportunities, diverse political alliances, and stronger cultural ties for the Metis. Demand for buffalo skins dominated the borderland region in the mid-nineteenth century. Independent Metis hunters and traders crossed the border into America to acquire buffalo skins for sale to the highest bidder, Canadian or American, that would otherwise be sold to the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) in Canada and bound for London.[3] Independent Metis traders used the border to capitalize on their unique position to make themselves attractive commodities to both nations. Metis traders successfully dismantled the HBC fur trade monopoly by diversifying the sources which they traded to, including American traders, which widened the Metis’ sphere of economic and political influence among the nations of America and Canada.[4] While in America hunting buffalo for their hide, Metis lived among their indigenous kin and often married Native American women. This deepened their heritage claims to America offering them somewhat of an anchor, albeit a shaky one, to both nations.

The enforcement of the U.S.-Canadian border highlighted American and Canadian prejudicial attitudes towards race. A reservation established in Montana for the Assiniboine, named Fort Assiniboine, served as a borderland trade and kinship hub for Metis and other people of indigenous heritage north of the border such as the Cree, Blood, and Blackfoot tribes.[5] Native migrant tribesmen traded goods such as liquor and ammunition and often married Assiniboine women to gain heritage claims in the U.S. while continuing to move between Canada and America. In August of 1881, pressures from fear of Indian aggression mounted. Ranchers feared foreign tribal hunting parties would use violence towards people and livestock to gain access to buffalo hunting lands, and, as a result, Agent Wyman Lincoln issued an injunction for the army to remove all trespassers from the reservation, including those that were white.[6] The injunction was carried out in October of 1881 by Lt. Robert Bates who issued a warning that all “…Crees, Bloods, Blackfeet, Salteaux Indians and Half Breeds now on the Gros Ventres and Assiniboine Reservation, or that have or may cross the Boundary Line,” were to vacate within five days or be forcibly removed by the military with no mention of mandatory vacancy to whites.[7] Enforcement of the border through racial injunctions and military force was a significant show of U.S. governmental power and their perspective that the border existed as a barrier to keep those exhibiting “otherness” out of America.

The North-West commission sanctioned an official land survey of the forty-ninth parallel. Canada and America worked together to devise a plan to complete the survey as peacefully as possible while enforcing the power of their nations. To accomplish this feat, the U.S. offered the U.S. 7th Calvary to accompany surveyors while Canada used their powers of persuasion to avoid violence with nearby Lakota and Dakota nations.[8] During the survey of the U.S.-Canadian border in 1873, British-Canadian officials manipulated the Metis into the borders creation by allowing them to continue to live near, and cross, the forty-ninth parallel provided they worked as diplomatic emissaries with Lakota and Dakota indigenous populations and as guides of the land.[9] The Metis, Canada, and America benefitted from symbiotic relations to Metis hunting and trading. America and Canada completed their land survey devoid of any major incident with the Lakota and Dakota nations, defined the forty-ninth parallel as the border, and gained income via international trade. The Metis remained in their borderland communities with unlimited access to buffalo and established trade and smuggling networks with Europeans and Native Americans.[10] Use of the U.S. military in conjunction with the Canadian allowance of the Metis to inhabit borderlands, and freely cross back and forth between nations, shows that enforcement and breach of the border equally significant as both barrier and passageway.

- Michael Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line: Creating a Border and Dividing a People, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 6.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 183-225.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 43.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 51.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 144-145, 149.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 145-149.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 149.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 92-95.

- Hogue, Metis and the Medicine Line, 97-100, 228-229.

The Bracero Program, Xenophobia, and The Mexican-American Border

America provided the hope of unimaginable economic and social opportunity for foreign immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century. Sadly, fear of “otherness” limited the number of immigrants that legally crossed international borders. Americans expressed their xenophobic attitudes in society and, more formally, through their immigration policies. A series of immigration policies passed in the early twentieth century raised borders in America higher and higher by excluding more types of people including those in Asian countries from ever being eligible for citizenship. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 was the ultimate declaration of non-white, non-European immigrant exclusion and use of the border as a barrier. The immigration policy “…restricted immigration to 155,000 a year, established temporary quotas based on 2 percent of the foreign-born population in 1890…excluded from immigration all persons ineligible for citizenship, a euphemism for Japanese exclusion.”[1] The Act not only excluded the majority of people from non-European countries but also placed no restriction on immigration from countries in the Western Hemisphere which the U.S. needed for an agricultural labor force and amiable foreign relations, particularly Mexico and Canada.[2] Proponents of tough immigration policies included social Darwinists and Eugenicists from all walks of life who sought to eliminate social ills, such as poverty, believed to be a prominent disease among non-white, non-European foreigners. Japan took great offense to the policy that it retaliated against the U.S. by imposing a one-hundred percent tariff on goods from America and felt that the policy guaranteed their disenfranchisement and social subordination within the U.S.[3] The strict immigration policies imposed and enforced on Asiatic and European nations at the turn of the century were significant barriers to cultural, political, and economic growth and stability.

Immigration policies concerning the Western Hemisphere seemed almost non-existent when compared to the restrictions placed on Asiatic and European countries. Mexicans escaped official government restriction on immigration during the 1920’s and 30’s and their ability to gain citizenship despite their “non-whiteness.” due to America’s necessity for agricultural labor in the southwest and beneficial foreign relations with Canada.[4] Mexicans suffered from racialized alienization in the U.S. despite their classification as “white” in terms of citizenship eligibility. Deemed unfair to impose restrictions on Mexico and not Canada, the U.S. found a loophole by which to restrict Mexican immigration in 1929. The State Department decided to use unofficial administrative means and the number of visas issued to Mexican immigrants in 1930 dropped by seventy-six percent.[5] The decline in visa approval did not see a decline in Mexican entry. Illegal immigrants, both Mexican and European, migrated across the U.S.-Mexican border at “unofficial points and avoided inspection” as Mexico remained the most heavily flooded pathway for illegal European immigration.[6] Breach of the Mexican border in the 1920’s and beyond provided cheap labor to southwestern farmers. Government officials in the 1950’s, like Senator Pat McCarron, supported illegal to legal immigrant labor because “a farmer can get a wetback and he does not have to go through the red tape…The agricultural people, the farmers…want this help…They cannot get along without it.”[7] In this way, breach of the border was a passageway to American farmers to gain cheap labor for agricultural business which shaped the U.S. economy.

Necessity for cheap migrant labor spurred the Mexican-American bracero contract labor program beginning in 1942 until 1964. Agribusiness exploded into a mass industry and company farms sought to increase workers and decrease costs. The bracero program brought, on average, two-hundred thousand workers across the border each year.[8] Employed by agribusiness industries, braceros agreed to be contract laborers devoid of U.S. military obligation in exchange for guaranteed work, wages, repatriation, transportation, housing, and food.[9] Employers often did not abide by the rules of the contract undercutting wages with little to no repercussion while migrant workers who broke their contract became illegal immigrants. Braceros benefited from the program, and the border as a passageway, because, despite being subject to underpayment, the wages made in the U.S. outweighed income opportunities in Mexico with many regarding the program as an avenue by which to “make a lot of money.”[10] Though the wages were better in the U.S. than in rural Mexico, migrant workers endured harsh working conditions and struggled to truly help their families back home.[11] The enforcement of the bracero labor program policy created a bureaucratic barrier to Mexican workers in gaining citizenship and permanent residency but also served as a passageway to better wages than their country offered.

- Mae Ngai, Impossible Subject: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004), 23.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 23.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 49.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 50.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 55.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 55, 66.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 255.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 139.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 139-140.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 141-142.

- Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 141-142.

Criminal activity, corruption, and cultural customs have influenced borders since the nineteenth century serving as a significant circumstance of border barricade and pathway.

— AllorahPros and Cons of Enforcement and Breach

Border enforcement served as divisional barriers both within and outside of the bureaucratic sphere. Relationships between immigrants, natives, and nationals served as cultural glue in borderland regions. Diplomatic relations and economic trade depended upon the solidity of cross-cultural relationships. In the early and mid-nineteenth century California belonged to Mexico and its population consisted of Mexicans, Native Americans, and U.S. western expansionists. Native Mexican officials, such as General Mariano Vellejo who served as the commandant for all northern California and as a rancho holder and alcalde of Sonoma and Petaluma, viewed their position as one of great responsibility in diplomacy between imperial and native nations, keeping the peace among those in their region, and providing for their native and immigrant agricultural labor force.[1] Vellejo employed tact and diplomacy in all his relationships. By participating in cultural activities from dinners with foreign emissaries to christenings of his workers’ children, passageway to facilitate better trade agreements and acquire stable trading partners and agricultural workers developed organically.[2] By contrast, seedy U.S. migrant trader John Sutter experienced the border as a barrier due to his poor relationships. Sutter imposed self-centered relationships upon Mexicans, European trade partners, and Native American agricultural workers. Sutter forced anchorage in California through enslavement of native workers, forced marriages between Europeans and Native American women, stealing of horses for trade income, and sowing deceptive lies to officials about his trade relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).[3] By all accounts, Sutter swindled his way into the borderland community with falsifications of his economic importance. Because of Sutter’s behaviors within and outside of California, Vellejo sided with a visiting HBC official, Sir George Simpson, when Sutter demanded that hunting by the HBC stop immediately.[4] Vellejo not only continued to allow HBC to hunt the land, he provided the hunting parties with rations each season much to Sutter’s disgust.[5] Participation in cultural customs, diplomacy, and morality opened the border for Mariano Vellejo while criminal activity, deceit, poor moral character barricaded economic opportunities across the California border for John Sutter.

Criminal activity, corruption, and cultural customs have influenced borders since the nineteenth century serving as a significant circumstance of border barricade and pathway. In the U.S.-Mexico borderland region of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, drug cartel activity and non-existent law enforcement plagued Mexico. In 2007, the Ciudad Juarez, the Juarez Cartel, better known by local inhabitants as La Linea, controlled everything from politicians, to law enforcement, to sports teams.[6] The rampant cartel violence, corruption, and control keeps the people of Cuidad Juarez oppressed and unable to seek a better existence in the U.S. and impossibility for most of the population. La Linea pays the drug czar and the Chihuahua state attorney to turn their heads to illegal activity.[7] The local cartel even influenced The Indios, a local soccer team and symbol of hope for residents. The color of the Indios uniforms, maroon, and violent occurrences, like the murder of a rival player who caused the Indios to lose a game, serve as consistent reminders of La Linea’s presence.[8] In fact, La Linea itself means “the line” to impress upon its citizens that stepping out of line is not an option.[9] La Linea created fortifications to dissuade its occupants from leaving while also using the border as a funnel for their illegal drug trade, a paramount source of income for the Mexican government.[10] Unlike California in the early to mid-twentieth century, criminal activity, corruption, and relationships provided high walls of border enforcement and narrow passageways for those looking to escape.

- Ann Hyde, “Three Western Places: Regional Communities and Vesinidad,” in Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West 1800-1860 (New York: Ecco, 2012), 190-191.

- Hyde, “Three Western Places,” 190-195.

- Hyde, “Three Western Places,” 184-195.

- Hyde, “Three Western Places,” 194.

- Hyde, “Three Western Places,” 194.

- Robert Andrew Powell, This Love Is Not for Cowards: Salvation and Soccer in Ciudad Juarez (New York, NY: Bloombury USA, 2012), 7, 57.

- Powell, This Love is Not for Cowards, 57.

- Powell, This Love is Not for Cowards, 50. 57.

- Powell, This Love is Not for Cowards, 57.

- Powell, This Love is Not for Cowards, 173.

The infamous Trump wall - good idea or big mistake?

Barriers and Passageways Make Borderlands History Relevant

Metis buffalo hunters and tradesmen’s mixed cultural heritage afforded them the experiences of racial discrimination and advantageous political power at differing times along the forty-ninth parallel. Xenophobic attitudes in America produced enforced immigration policies like the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 that completely barred those from Asiatic countries from legal entry. Breach of the U.S. border for Mexicans and Europeans provided an avenue by which to attempt to make their lives better than what the existing possibilities within their own countries. The Bracero program melded the ideas of enforcement and breach by offering labor opportunities to rural Mexicans. Cultural customs and relationships dictate the borderland region experience as barrier or passageway. Criminal activity influences the ease or difficulty with which relations can across borderlines. Since the nineteenth century, international borders continuously provide examples of their enforcement and breach significant as both barrier and passageway. Borderland regions facilitate the enforcement and breach of government policy, cross-cultural economic gain, and cross-cultural practices aimed at anchoring the populous to one or both sides of the border. It is in these ways that both the breach and the enforcement of borders from the nineteenth century forward are significant in the history of borderlands.

Bibliography

Hogue, Michael. Metis and the Medicine Line. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Hyde, Ann. “Three Western Places: Regional Communities and Vesinidad.” In Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West 1800-1860, 640. New York: Ecco, 2012.

Ngai, Mae. Impossible Subject: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Powell, Robert Andrew. This Love Is Not for Cowards: Salvation and Soccer in Ciudad Juarez. New York, NY: Bloombury USA, 2012.

© 2018 Allorah