One hundred years of discoveries: Troy

Almost three thousand years ago Homer, a blind epic poet, was writing one of the most fascinating stories ever told, stories about heroes, fortresses with impenetrable walls, adventurous journeys of great kings and warriors, fantastic creatures, the most beautiful woman in the world and eventually, the ten years war that she will cause. It was a time when the Gods were messing around with humans destinies at their own will.

The dream

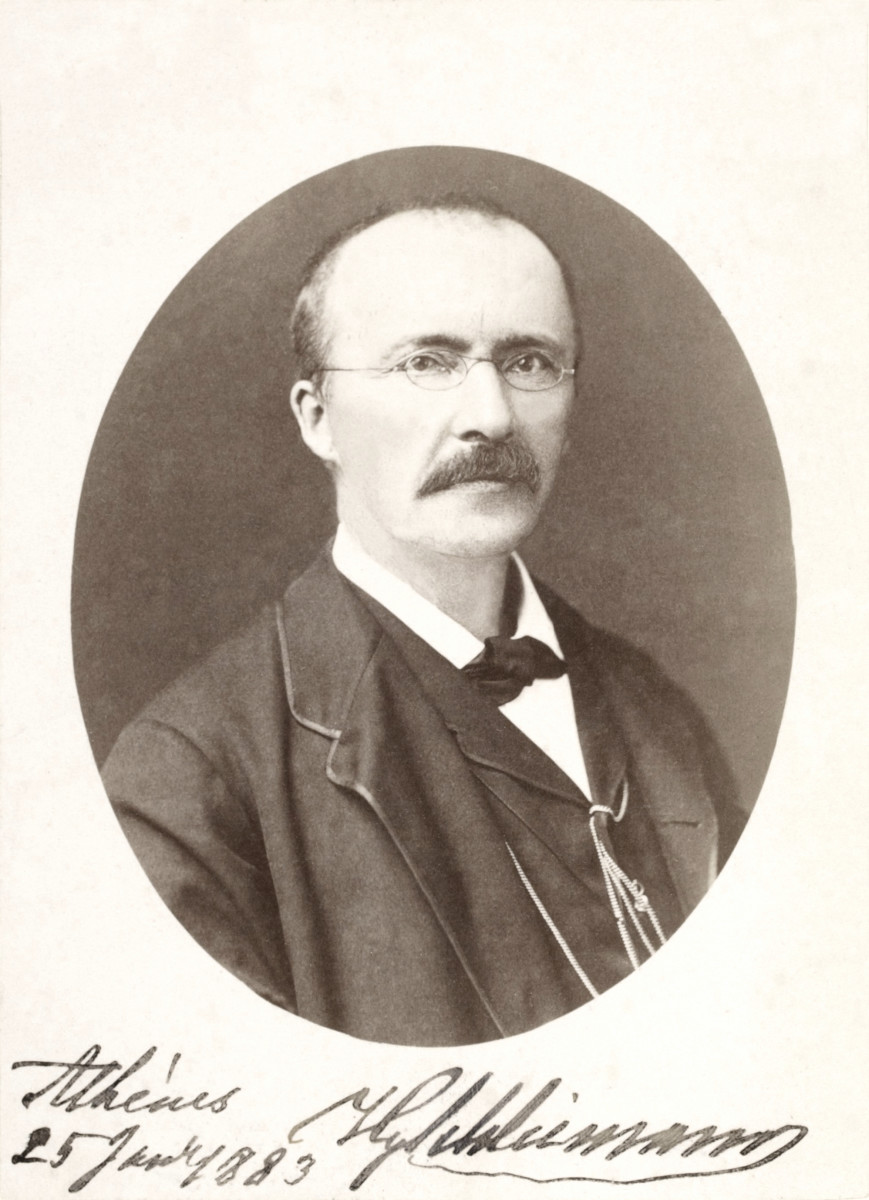

For almost two thousand years, Troy (or Ilion) was just another legend. However, this legend captured the ten years old Heinrich Schliemann’s attention when he received a picture book from his father for Christmas. The book was picturing the siege of Troy and Odysseus’ ten years trip back to his homeland, Ithaca. He became fascinated by these stories, and soon young Heinrich began to ask himself how could the fortress with the most fortified walls in history vanish? From that moment on, finding Troy became his lifetime dream.

Surprisingly, he did not follow archeology, but at his forties he was able to speak fluently several languages, including (ancient and modern Greek), which helped him to attend profitable jobs. At 45 years old he decides he has enough funds to begin the search for Troy.

The quest

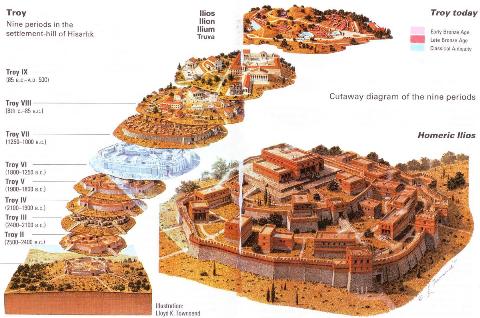

Following clues in Homer’s Iliad, he is able to accurately identify Troy on a hill in ancient Anatolia (named Hisarlik in modern northwestern Turkey). It is said that one day he was so tired that he fell asleep on the wet grass, during a rain. He found massive walls, a gate large enough so two chariots could enter the fortress at once (exactly the way Homer tells us in Iliad) and finally, he finds what he thought it was the jewelry worn by Helen, a great quantity of gold and jewels that he later manages to pass out of the country. Fortunately (or unfortunately for him) the discoveries do not end here. When dealing with ancient structures, there is one significant problem: almost every civilization that lived in that place constantly modified it, building over the older structures. In his conviction that the homeric Troy would be found in the earliest layers, he demolished many interesting structures from later eras, including all of the house walls from Troy II. In addition, the deeper he was digging, the less probable was that the treasure he found was Helen’s. In the years that came, he refined his search, and after his death in the late 19th century, others continued his work.

It is now known that there are nine layers of ruins of Troy with various subdivisions and that the Homeric Troy corresponds to a layer somewhere between the sixth and the seventh (Homer lived during Troy VIII era). However, the search was not over, not even close. Few other problems needed to be solved.

1. Mycenae

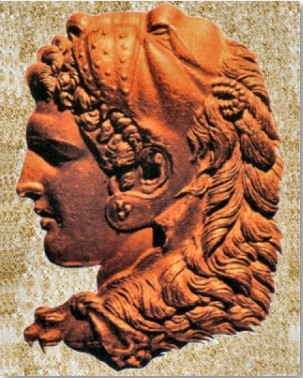

If Troy was real, so must be Mycenae. Schliemann’s second target was Agamemnon’s great kingdom of Mycenae, which he found in ancient Peloponnese in modern Greek territory. Unlike Troy, Mycenae revealed to him in its entire beauty: the lions guarding the gate, the ruins of the palace, the tombs and the treasures inside them was more than even he was expecting. The tombs belonged to important people of those ages, most probably kings and queens. This mask belongs to a late Bronze Age king.

Schliemann’s imagination was very agile. He believed – or wanted to believe – that the golden face was portraying King Agamemnon himself. Some say that Schliemann actually took it to a local blacksmith and sculpted its mustache.

2. Too small for a ten years war

The ancient city on the hill of Hisarlik was too small to bear a ten years war against one of the greatest military powers of that time, the Achaeans lead by Agamemnon, king of Mycenae. In the late nineties Manfred Korfmann continued excavations along the coast of the Aegean Sea at the Bay of Troy, finding possible evidence of military conflicts in arrowheads found in layers dating back in early 12th century B.C. In 2003, Korfmann came back to Troy to continue his study, this time helped by a magnetic imaging survey of the fields below the fort. What he found was what he hoped for: a large area of later ruins (Greek and Roman) beneath the ground. He later was able to excavate a ditch surrounding a vast area around the fort and successfully dated the remains found in it in the late Bronze Age, and it is believed that once served as outer defenses against chariots for a much larger city.

3. The Trojan War

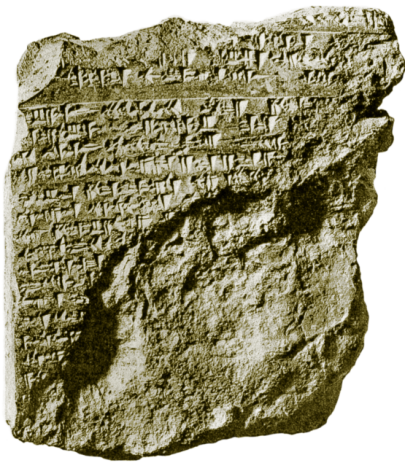

Although Troy and Mycenae were real, there was no evidence that this Troy was besieged by Achaeans. The evidence came this time from the Hittites who occupied a vast territory from Troy towards east. The Hittites wrote of a city in ancient Anatolia near the Aegean Sea, named Wilusa, and only recently the evidence that Wilusa and Troy are the same location has been found when Korfmann and his archeological team excavated a water tunnel at Troy (initially thought to be roman), which is mentioned in one of the Hittites’ inscriptions regarding Wilusa. The tunnel has been dated in 2,600 B.C.

The Hittites also wrote about Alaksandus, king of Wilusa, now identified with Prince Alexandros or Paris, of Troy, and even that Wilusa witnessed a confrontation between two leaders of armies, which can be associated with the battle between Hector and Achilles or Menelaus and Paris.

An unnamed Hittite king wrote a letter to the king of the Ahhiyawa, treating him as an equal and implying that Miletus (Millawanda) was controlled by the Ahhiyawa, and also referring to an earlier "Wilusa episode" involving hostility on the part of the Ahhiyawa. This people have been identified with the Homeric Greeks (Achaeans).

Studies made at the archeological site of Mycenae shown that the late Bronze Age was a period characterized by fortune, luxury. The problem that Mycenae was facing was the lack of natural resources, and this forced the Achaeans to search for luxury somewhere else. On the other hand, Troy was strategically situated at about 6.5 kilometers from both the Aegean Sea and the Dardanelles and it is believed that it was controlling the whole trading routes in the area. Several large ditches (now partially) connecting the Aegean Sea and the city of Troy are suspected to be artificial, so in the Troy’s age of glory those ditches were meant to facilitate trading ships bringing goods directly into the city.

Troy was a carved target, therefore major conflicts with the Achaeans are very likely to have happen, however we’ll probably never know if Helen was the reason of the Trojan War or not, nor if there has been a Trojan horse that the Achaeans tricked the Trojans with.

Additional info

Schliemann's fascination did not know limits

In the second half of his life, Schliemann divorced his former wife and married a seventeen years old Greek girl, Sophie. The first thing he did after finding the Troy’s treasure was taking a picture of his wife wearing what it was supposed to be Helen of Troy’s jewelry. Later on he succeeded slipping them out of the country and selling them to a museum in Belgium. The treasure still remains a subject of dispute between Turkey, Germany, Greece and Belgium although its authenticity is more or less contested.

Alexander the Great

Unlike Troy VIII, which was a small Greek city, Troy IX was the city of Ilium, ruled by the Greeks and later by the Romans. Alexander the Great held athletic games there in the 300s B.C. to honor Achilles, from whom he believed himself to be descended. In the same period he actually visited Achilles' tomb which was supposed to be buried under a small hill somewhere between Troy and the Aegean shore, never identified by now. The city lasted until the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great in the 300s A.D.

Odysseus' Ithaca

After unveiling Mycenae, Schliemann continued his quest in modern Ithaca to find Odysseus’ palace and all the other places mentioned by Homer in the Odyssey. He thought he did, but recent studies lead by Robert Bittlestone shown that Odysseus’ Ithaca could be in fact the Paliky peninsula situated in the western Cephalonia, where he pretends he identified many (if not all) locations mentioned in Odyssey. One of Strabo's texts also sustains Bittlestone's theory. He writes about Ithaca that "in its narrowest side it forms an isthmus so low-lying that it is often submerged from sea to sea". At this moment, this research is still in progress.

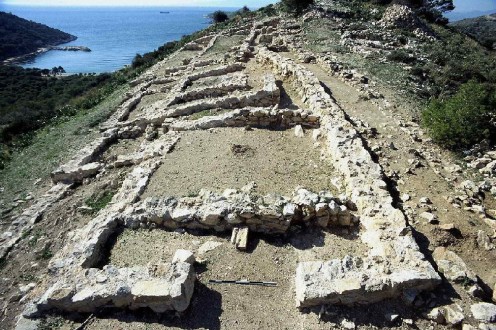

The palace of king Ajax the Great

Greek archaeologists say they have unearthed the remains of a 13th Century B.C. palace linked to the legendary warrior-king Ajax. The ruins, situated on the western Salamis, show that the palace had four stories and at least thirty three rooms. Ajax the Great is one of the heroes who fought in the Trojan War, next to Achilles, Odysseus, Menelaus and many others.