Pediatric Medical Home Financing Policy Recommendations for Florida by Brian Brijbag

Introduction

Established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the medical home model is an innovative ideal for providing comprehensive care for pediatric patients. This “patient-centered” healthcare delivery system seeks to improve the experience of care by increasing access, improving coordination amongst stakeholders and strengthening provider-patient partnerships while reducing costs associated with health services. The medical home incorporates the treatment and prevention of developmental, chronic and behavioral health issues while also addressing the varying basic services that form the fundamentals of pediatric services.

At the national and local level, the principles of a pediatric medical home have been established as a priority in health policy reform. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), within the goals of Healthy People 2010, stated, “all children with special health care needs will receive regular ongoing comprehensive care within a medical home” (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Yet public and private payers in Florida have hindered the full implementation of this program due to the lack of financial backing through an adequate payment structure that places value on pediatric medical homes.

Brian Brijbag Child Health Policy

Medical Home Essential Services

The medical home is a team-based approach to healthcare that is led by the adolescent’s primary physician. The definition of a “medical home” is intentionally flexible to allow for innovation within the standards set forth by governing bodies such as the AAP. It is widely understood that a medical home should essentially include:

- “Well Child Care” services for all adolescences. This includes screening for additional necessary services that may be required which fall within the expanded scope of a medical home. Routine visits should be monitored, and a scheduling plan developed with the family, to assure that the child maintains a consistent care plan. Finally, families found to have fallen behind on their routine care plan, including immunizations, should be contacted and followed-up with by staff.

- Chronic conditions must be managed across providers – This will include coordinating care among all pediatric sub-specialties, behavioral care providers and community-based support groups.

While providing many of the aspects that make-up the essential services of a pediatric medical home, providers are often offered little or no reimbursement for the care provided. Uncompensated services may include:

- Coordination with pediatric specialists, schools, community-based support groups

- Communication with the family including phone conversations and emails

- Navigating health insurance issues

- Completing the necessary forms for schools, social services, insurances or other providers

Medical Home in Current Policy

Residing within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Affordable Care Act (ACA) created the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010). It is here that models which promote innovated payments and services such as the medical home can be tested. This allows HHS to explore scenarios for medical home financing that moves from a fee-for-service reimbursement structure towards a comprehensive or salary payment model.

Additionally, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act develops incentives for providers to invest into electronic health records (EHR). Under Medicare and Medicaid, providers that can exhibit and attest for “meaningful use” of EHRs can receive financial benefits in the form of bonuses. The use of EHR in a pediatric medical home is a key component of care coordination.

Issues in Financing the Medical Home Concept

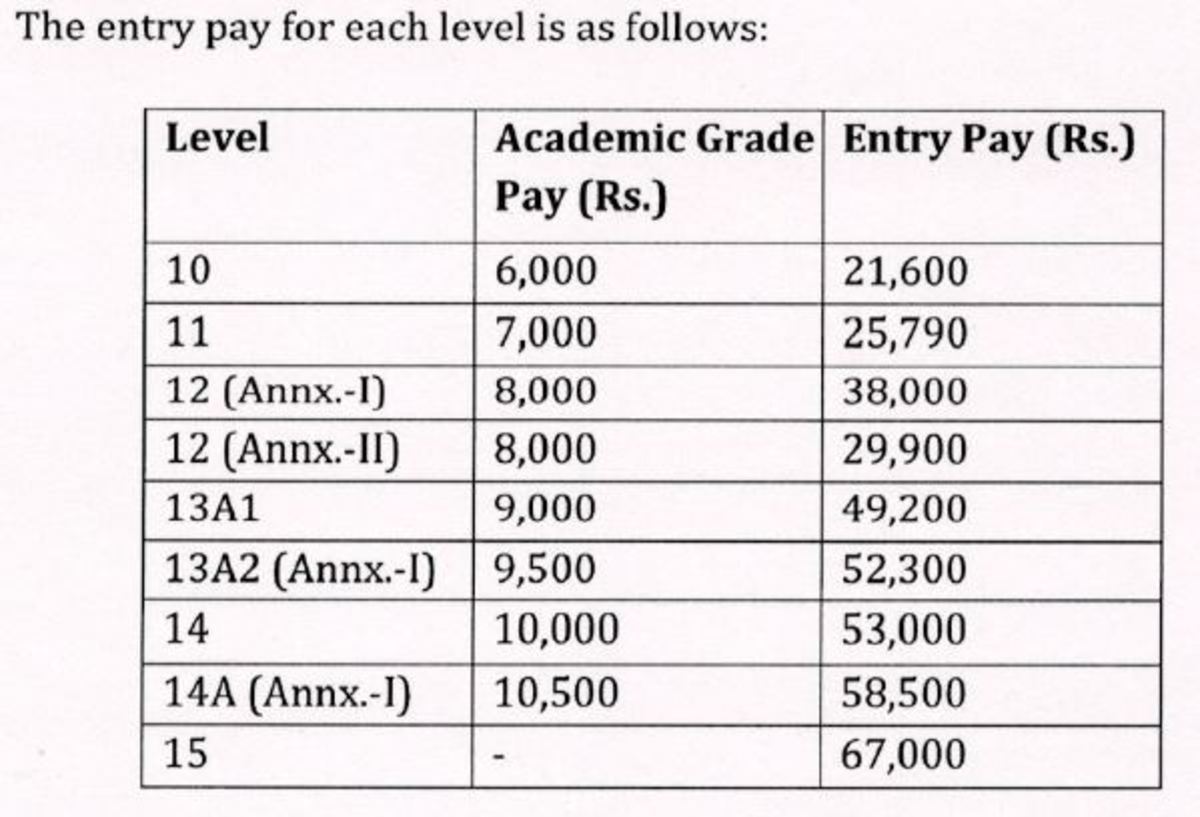

In her testimony before Congress, Dr. Judy Palfrey, then President of the AAP, stated that, “there is good evidence that appropriate payment of providers will result in children having better access to comprehensive health services in a medical home” (J. Palfrey, Congressional Testimony, June 11, 2009). The incentives to introduce and maintain a pediatric medical home must be realistic towards the level of practice redesign and care demanded by quality patient outcomes. The resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) fee-for-service payment structure places the pediatric physician at an economic detriment.

For example, using the average state Medicaid reimbursement figures, pediatric physicians are paid at a rate amounting to 72% of the Medicare rates of adult healthcare providers (Palfrey, 2009). It must be acknowledged that pediatric staffs do not complete 28% less work than their family practice counterparts. Nor do pediatric physicians enjoy expense discounts, such as office leases or medical supplies, which make up for the inequities in the payment structure. Medicaid payments, for similar services, must be equal to Medicare rates to correct the disparities and biases towards physicians whom primarily deal with children.

Why Finance Medical Home?

Through the medical home concept of managing pediatric care, the physician can access and coordinate the multiple services, both medical and non-medical, that are important to overall health. This coordination of care is “associated with improved levels of satisfaction, decreased hospital and emergency room use and lower costs” (Strickland, B., et al., 2004).

These lower costs are often associated with children who have special needs, yet current research has concluded that for children without special medical needs, the medical home is also “associated with improved health care utilization patterns, better parental assessment of child health and increased adherence with health-promoting behaviors” (Long, W.E., et al. 2012). This same study found that the decrease in unnecessary utilization by those children without special needs in a medical home, led to an overall health care savings (Long, W.E., et al. 2012).

Florida PCMH Demonstration Project

Proposed Medical Home Payment Structure

When examining the characteristics of the medical home, it demands a rethinking of current pediatric payment fee structure. I propose a model of medical home payment that incorporates the following:

- Encounter based – This component of the payment model would provide value to the services currently seen as ancillary and are uncompensated. Services such as phone calls, emails or form completion could be paid as a fee-per-encounter or as part of a larger enhanced capitation payment model.

- Care Coordination Fee – This aspect of the payment model would recognize, and compensate, the work of coordinating care within the medical home community. This fee could be paid as a monthly fee calculated per plan member while taking into account adjustments based upon the intricacies of the patient panel. This fee could be reevaluated annually to consider the alterations in the regional cost of living indexes.

- Performance based – Lastly, a fee based on evidenced-based patient measures could be earned as a monthly bonus centered on predetermined quantifiable goals.

This fee structure incentivizes and compensates the stakeholders in a medical home. At the same time it avoids one of the major pitfalls of traditional managed care where the primary care physician is the gatekeeper of services. The physician as “gatekeeper” often implies that the physician as the one that limits needed services in order to minimize utilization and decrease costs. The medical home, with the proposed fee structure, encourages the pediatric physician to act as a facilitator of appropriate care as opposed to a gatekeeper. This reinforces the ideal of pediatric physician as a partner in care through the establishment of a medical home.

Recommendations

- Payment reform must be enacted to incorporate a fee structure among all private and public payers that supports the complexity of the medical home.

- The center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation should earmark assets to create, test and implement different methodologies for payment within a medical home services delivery system.

- Recognizing the value and significance of the work done within the pediatric medical home, Medicaid reimbursement rates should reach parity with comparable Medicare payments for all pediatric services.

Conclusion

It is my opinion that the medical home model is an integral part of a population benefiting, comprehensive healthcare delivery system. The medical home has been proven to contribute to marked improvements in areas related to increased positive patient behaviors, coordination of care and cost-effectiveness. The proposed recommendations presented herein will go a long away to resolving current deficiencies in the payment system while ensuring that pediatricians can offer an all-inclusive medical home for all adolescence in the United States.

Further Reading

For supplementary literature on the concepts related in this paper, please consider the following publications:

Support for Recommendations

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2002 reaffirmed in 2008). Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Pediatrics, 110(1):184-186.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2012). The Medical Home for Children: Financing Principles. Prepared by the Committee on Child Health Financing.

Further Details on Issue

- Nelson, P. J. (2008). Medical home policy recommendations. Center of the American Experiment, 1-5.

- Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E & Taba S. (2004). History of the Medical Home Concept. Pediatrics, 113(5):1473-1478.

References

- Long, W.E., Bauchner, H., Sege, R.D., Cabral, H.J., & Garg, A. (2012). The Value of the Medical Home for Children Without Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics, 129(1):87.

- Palfrey, J. (2009). How Health Care Reform Can Benefit Children and Adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine, 09(1):1-3.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2010). Patient-Centered Medical Homes. Health Policy Brief. Health Affairs, 1-6.

- Strickland, B., et al. (2004). Access to the Medical Home: Results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 113(5):1485-1992.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (1999). Measuring Success for Healthy People 2010: National Agenda for Children with Special Health Care Needs. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. http:// www.mchb.hrsa.