Pericles

Pericles was an Athenian statesman. Born in Athens, Greece, about 495 B.C. Born into the highest Athenian society, his father, Xanthippus, was a famous general, and his mother was a member of the powerful family of the Alcmaeonidae. His military education was supplemented by the tutoring of several distinguished men, including Damon and Anaxagoras. Their teachings reputedly rid Pericles' mind of common superstitions and opened it to democratic ideas.

Soon after Pericles entered the political life of Athens, he became the principal lieutenant of Ephialtes, leader of the democratic group that was struggling against the Areopagus. With the exile of Cimon, the aristocratic party leader, power passed to the democrats and then to Pericles, who assumed leadership of the party in 461 B.C. The next 30 years proved to be an almost unbroken period of Pericles' rule over the destiny of Athens. As dominant member of the board of generals (strategoi), he was the most powerful man in Athens. However, he was most influential as leader of the assembly, where his logic and eloquent oratory convinced the Athenians of the soundness of his policies.

Policies

Domestically, Pericles made important advances in the democratic machinery of Athens. Much of the power of the Areopagus was taken away and given to the bodies in which the common people had a voice. He instituted payment for serving in public office. Previously, people who were too poor to stop work to serve could not afford the financial burden. The basics of Athenian democracy were imposed upon the governments of the city-states that became part of the Athenian Empire.

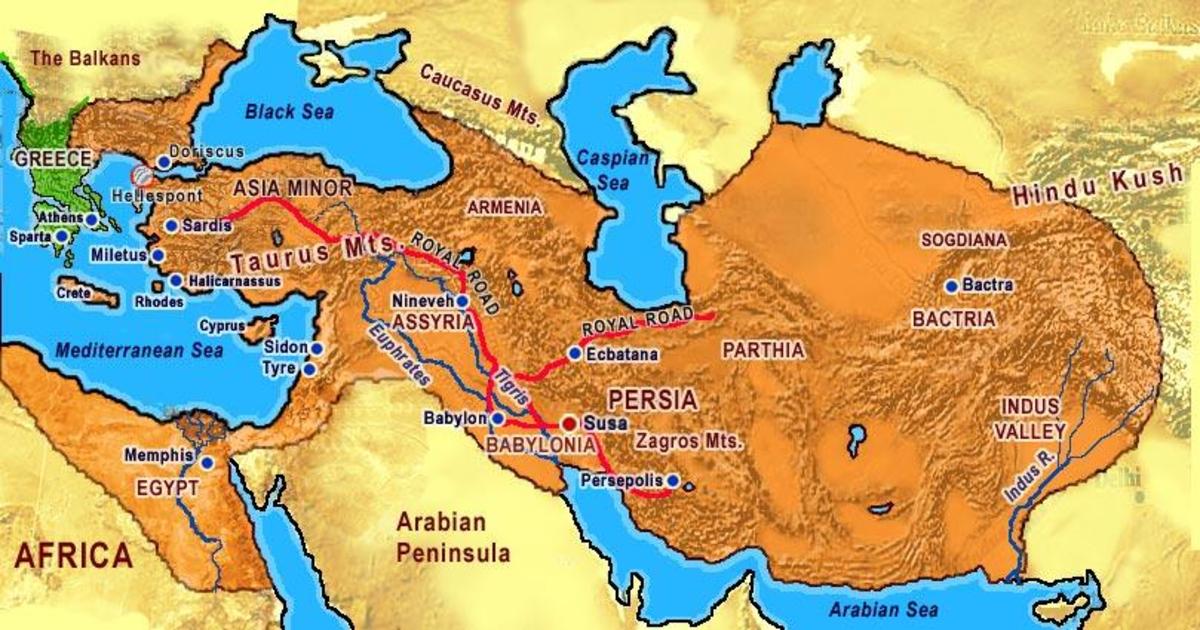

In the foreign sphere, Pericles brought Athens to the height of its influence and power. His goal was to make Athens the leading city in Greece. To accomplish this, he warred on several fronts. He continued to incorporate the members of the Delian League, or confederation of Greek states, into the growing Athenian Empire, subduing by force any city that wished to break loose. Although historians are not sure of Pericles' specific policies during the period, he probably favored sending a fleet to support the revolt of Egypt against Persia in 459 B.C. At the same time he struggled with wealthy Corinth for supremacy in Greek trade. The Egyptian adventure ultimately failed in 454 B.C. Encountering increasing resistance, which was led by Sparta, the wars that Athens waged in Greece met reverses. A more cautious policy caused Pericles to propose a Pan-Hellenic league to deal with the problems of the city-states, but the league was rejected in 448 B.C. because Athens obviously would have dominated it.

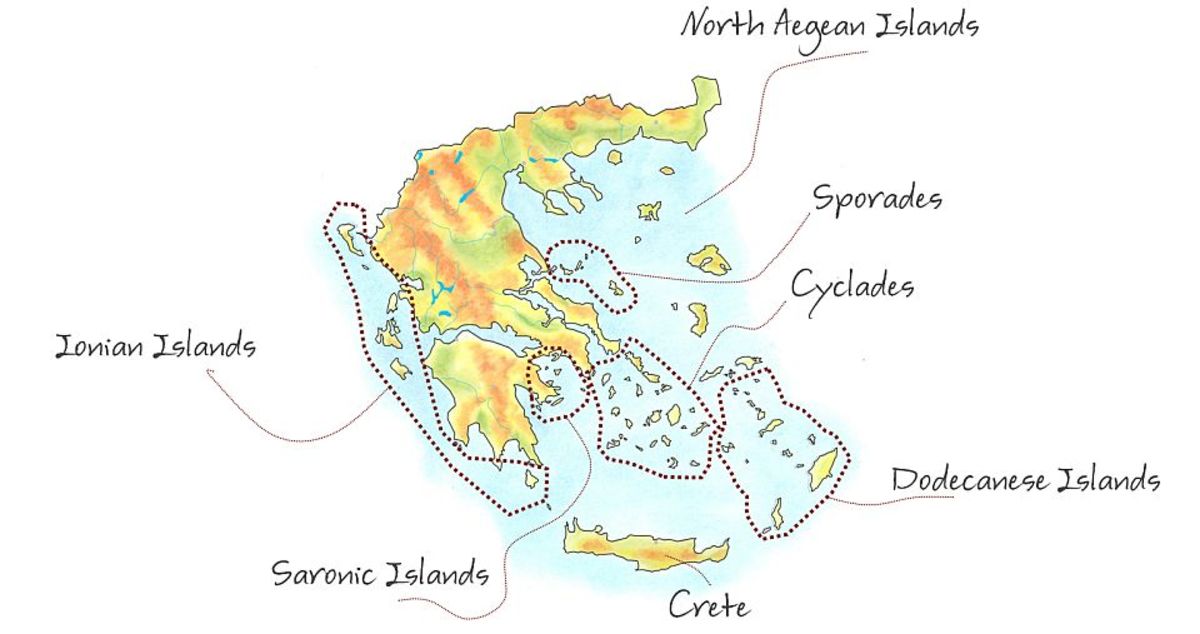

Peace was made with Persia in 448 B.C., and a 30-year peace was made with Sparta in 445 B.C. Efforts to extend Athens' control of a land empire failed, but the city was dominant on the sea. Colonies had been established in the Black Sea, in southern Italy, and throughout the Aegean Sea, and Athens became the leading commercial city in Greece. In 454 B.C., Pericles moved the treasury of the Delian League to Athens, thus solidifying his hold on the allies and giving the city an important source of revenue.

The Golden Age of Athens

In the 14 years that followed the 30-year peace, Pericles realized his goal of making Athens the cultural center of Greece. The period of Pericles' rule is known as the Golden Age of Athens or the Age of Pericles because of the presence of the many giants of art, literature, and philosophy and because of the spread of Athenian influence. The age reached its climax with the beautification of the Acropolis, as conceived and directed by Pericles. He saw the necessity of replacing the temples and statues that had been destroyed during the Persian Wars and of paying homage to the gods, especially Athena, for Athenian good fortune. He did not hesitate to use the funds from the Delian League to pay for the construction.

Pericles also used the funds to strengthen the military power of the city because he believed a war with the forces of the Peloponnesus was inevitable. The navy was expanded, the Piraeus was rebuilt, and a new wall from Athens to the Piraeus was constructed. The city was prepared for siege.

The Peloponnesian War

When war threatened, Pericles exhorted the Athenians not to shrink from it. He had prepared well for the struggle and felt his plan of battle would eventually exhaust the attackers. His plan was to allow the enemy to take the land around Athens, after which he would house the displaced population within the city. He reasoned: "Mourn not for houses or lands, but for men; men may give these, but these may not give men." He wanted to avoid a battle on land, where the enemy was stronger, and to have the powerful Athenian fleet free to disrupt the commerce of their assailants.

Pericles' view of Athens after 30 years of his guidance is shown in his funeral oration given for those who died in the first year of battle. It gives a solemn, but noble, message to the grieving Athenians concerning the greatness for which they fought, the glory of incomparable Athens.

In 430 B.C. the plague entered Athens, killing great numbers of the city's defenders and seriously hindering its fighting ability. Several defeats were sustained, and the demoralized people ousted Pericles. However, he was soon restored to office with increased powers. Shortly afterward, Pericles died of the plague, and left Athens without a successor capable of equaling his greatness.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2009 Historia