The Peterloo Massacre

Massacre

It was named The Peterloo Massacre as it happened four years after the Battle of Waterloo which ended the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The massacre happened at St. Peter's Field in Manchester.

Reform required

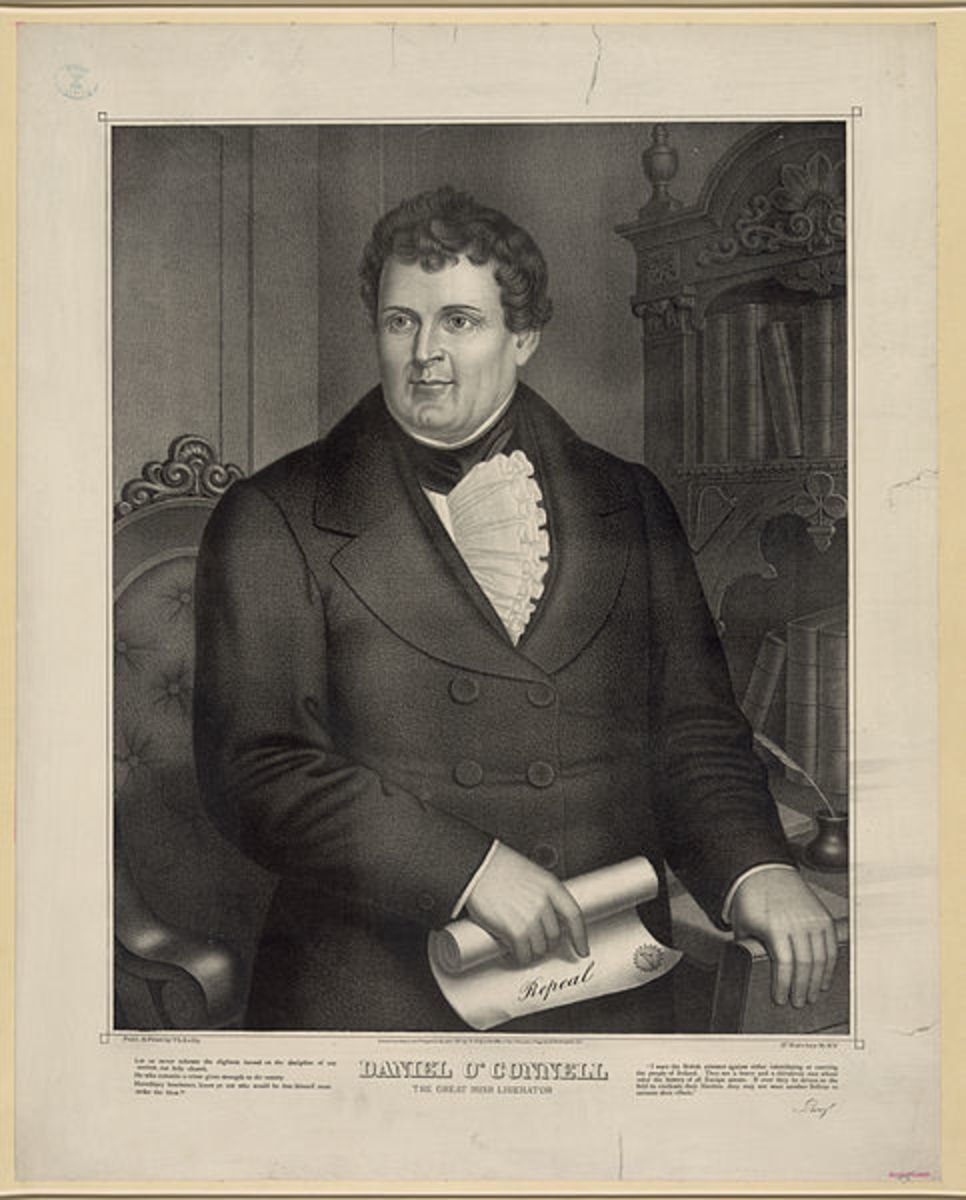

The men of Manchester tried to get the Houses of Parliament to change the law so that they would have more than two members of parliament to represent their county. There were a million people in the county, the boundaries were out of date and what were termed, 'rotten boroughs' were causing disproportionate representation in Parliament. A 'borough' was a town that had the Royal Charter giving it the right to elect two members to the House of Commons. When a town expanded, the borough didn't alter its boundaries, so that the borough and the town were no longer identical in area. The true rotten borough was a borough with a very small electorate. Rotten boroughs had representation in parliament when they were centres with a substantial population, but with boundary changes they had shrunk in population, but still maintained their MP's. So a borough with just a few people had two representatives while a borough with many thousands still had only two. The majority of voters were concerned that boroughs with just a few voters could be bribed or swayed to vote a particular way. A borough in Wiltshire called Old Sarum had only one voter, yet it had two MP's.

The whole county of Lancashire, of which Manchester was a part, had two MP's in 1819.

Union Formed

After the war with Napolean in 1815, a boom in the textile trade was suddenly followed by depression. Workers who were earning15 shillings for a week in had their wages cut to 5 shillings. The bosses were cutting wages and were blaming the market slump on the War. Parliament brought in the 'Corn Laws' charging a high tariff on foreign grain imports to protect English grain producers. Food became extremely expensive as people were forced to buy their grain from British producers, even though it was a lower quality. A group calling themselves, 'The Manchester Patriotic Union,' who were agitating for parliamentary reform, called a general meeting at St. Peter's Field. Joseph Johnson, the secretary of the union, wrote to a radical speaker called Henry Hunt and asked him to address this meeting planned for 2August 1819 in Manchester.

Unfortunately the letter was intercepted by a government spy and copied before being sent on to Hunt. Parliament decided that an insurrection was being called, and the government immediately responded by ordering troops of 15th Hussars to Manchester.

The public meeting planned for 2nd August had to be delayed until 9th August, and The Manchester Observer, a newspaper in the city announced the delay and also reported that the intention of the meeting was to reform the House of Commons, and for the unrepresented people of Manchester to elect a person to represent them in Parliament. The local magistrates in Manchester were instructed that this was an illegal act as an MP had to be in possession of the King's writ before he could serve the public. They were therefore instructed to declare the meeting illegal.

The Union, heard the instruction to dissolve their meeting but they refused.

On the morning of the meeting, the local magistrates gathered at a house on the fringes of the field to observe the proceedings, as they were concerned that it could end in a riot. They had instructed the armed forces to stand by and the military presence consisted of 600 men of the 15th Hussars, several hundred infantrymen, a unit of the Royal Horse Artillery with two six-pounder guns along with 400men of the Cheshire Yeomanry, 400 special constables and 120 cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry.

Disaster

When the chairman of the

magistrates saw the enthusiastic reception that Hunt received from

the 60,000 to 80,000 people gathered at the meeting it forced him

into action. He issued a warrant for the arrest of Henry Hunt,

Joseph Johnson and others of the organisers. The Chief Constable

suggested that the huge crowd surrounding the speakers would make

military assistance necessary, to serve the warrant. The Chairman

wrote two letters, one to the commanding officer of the Manchester

and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other to the Commander in Chief

of the forces in Manchester. Both letters intimated that the Civil

Powers were not enough to preserve the peace.

The

Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were a short distance away received

their note first. They drew their swords and galloped towards St

Peter's Field. In their mad dash, a woman with a child in her arms

was knocked down, and the child was thrown from her arms and killed.

The Magistrate told the commander of this troop that he had an arrest warrant which he needed assistance to execute, and he was asked to take his cavalry to the dais to allow the speakers to be removed.

The route they took to the dais was straight through the crowd and as the horses were pushed further and further into the throng they started to panic, rearing and plunging as people tried to get out of their way. The troopers, in panic, started to slash about them with their sabres, and the crowd, incensed, started to throw bricks at them. On his arrival at the dais the officer with the warrant arrested Hunt, Johnson and a number of others, and his men started destroying the banners and flags. The Chairman of the Magistrates saw that the troops were being stoned and as the 15th Hussars arrived on the scene he ordered them to disperse the meeting.

The Hussars formed themselves into a line stretching across the eastern end of St Peter's Field and charged into the crowd. At the same time the Cheshire's on the southern edge charged. The crowd were caught in the middle and tried to scatter, but the 88th Infantry Regiment had closed up and were threatening them with bayonets fixed. An officer of the Hussars was heard trying to restrain the out of control Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, who were cutting at every one they could reach, 'Gentlemen, desist, the people cannot get away!'

The crowd finally dispersed, but 11 were dead and between 600 and 700 were injured.

The National papers shared the horror felt by the Manchester citizens, and the feelings of rage throughout the country became intense. The name 'Peterloo' was invented immediately by the Manchester Observer, joining the name of the meeting place with the Battle of Waterloo fought four years earlier.

One of the casualties an ex-soldier, who died from his wounds on 7 September, had fought at the Battle of Waterloo, and shortly before his death he told a friend that he had never been in such danger as at Peterloo: 'At Waterloo it was man to man but there it was pure murder.'

Accounts of the massacre were headlines in the papers right across the country.

After a short trial five of the ten defendants were found guilty. Hunt was sentenced to 30months in jail; Bamford, Johnson, and Healey were given one year each, and Knight was jailed for two years.

The government gave out a statement supporting the actions of the magistrates and the army.

Peterloo had no effect on the reform of the election system. It was not until 1832 when the 'Great Reform' act was passed, that the newly created Manchester Borough elected its first two MPs.