Put Down the Kendi and Do Your Homeworks! Philippine English: Dialect of the Islands

Necessity of 'Taglish'

[Originally published in 2011]

As the third largest English-speaking population, the people of the Philippine Islands are unlike other previously-colonized groups. The widespread use of the language in formal and informal speech has remained a heavy influence on the dialects of the islands as well as the formation of the Philippine’s particular branch of English. Philippine English itself is a version of English that uses standard American rules for the most part, but possesses many rules and functions peculiar to the Philippines. An American would probably have no problem understanding a speaker of this English, but would easily characterize the speech as ‘Philippine English,’ much to the annoyance of the Filipino, who is speaking what he was taught as the ‘standard’ (Cruz, IV). While nearly all Filipinos speak English as a second, third, or maybe fourth language, they don’t all use the exact same dialect. The accent and usage will vary according to which language group the speaker comes from. This could be any of eighty-seven ethnic groups, which contain over one hundred languages (Nero, 265).

Filipino and English

This variation becomes a problem when students graduate from their local schools and seek a university career. The national standards and tests are all in a strictly standard form of American English that only a small portion of the population, mainly those in large cities, are exposed to (Bautista, 76). The other official language, declared in 1935, is Filipino, originally called ‘Pilipino,’ which is a form of the most widely-spoken native language, ‘Tagalog’ (Bautista, 143). Filipino also includes aspects from many of the other most populous languages, such as Hiligaynon and Bikol. The use of English in the Philippines, which began as an effort of colonization and became the practical solution to islands that had little prior linguistic unity, has been challenged by the emergence of Filipino, but remains a useful avenue of communication that is difficult to undo from Philippine society (Bautista, 142).

English replaces Spanish

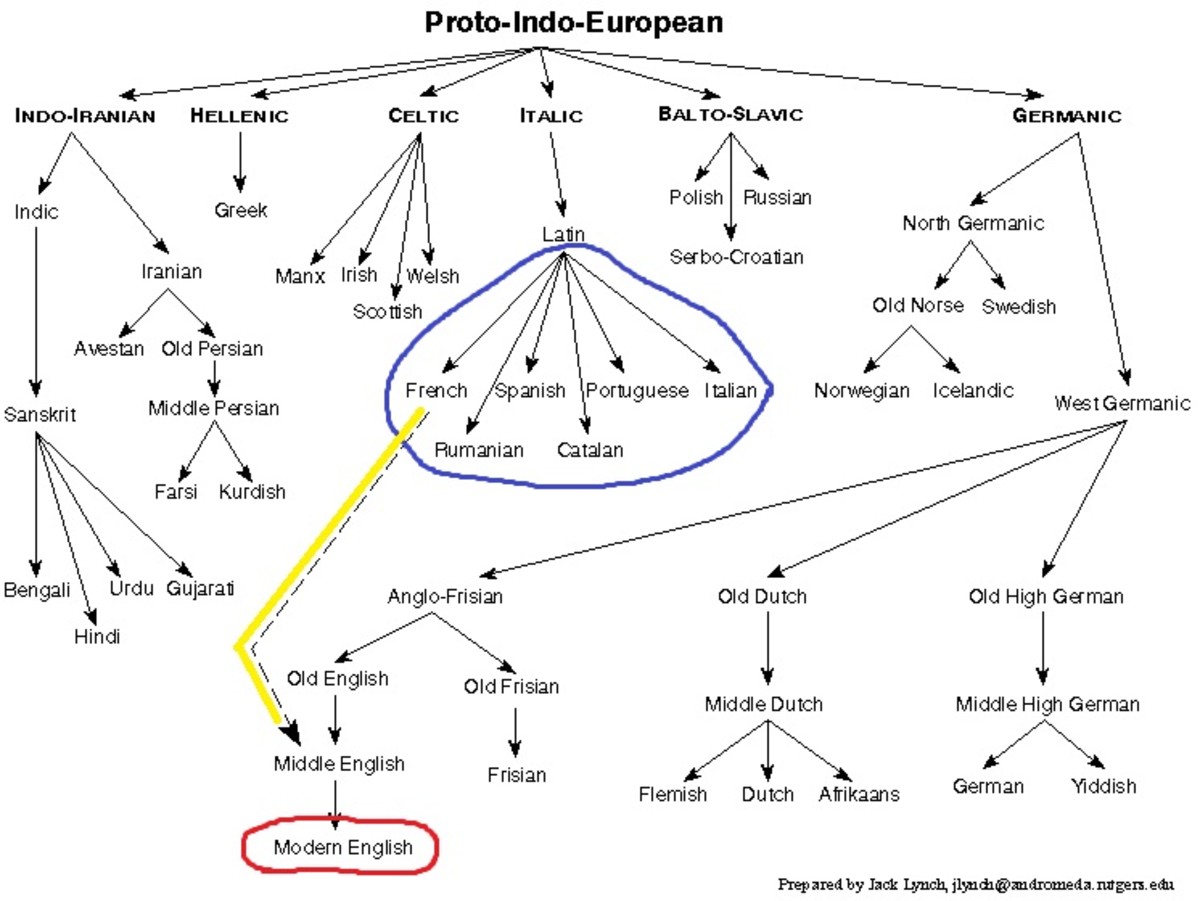

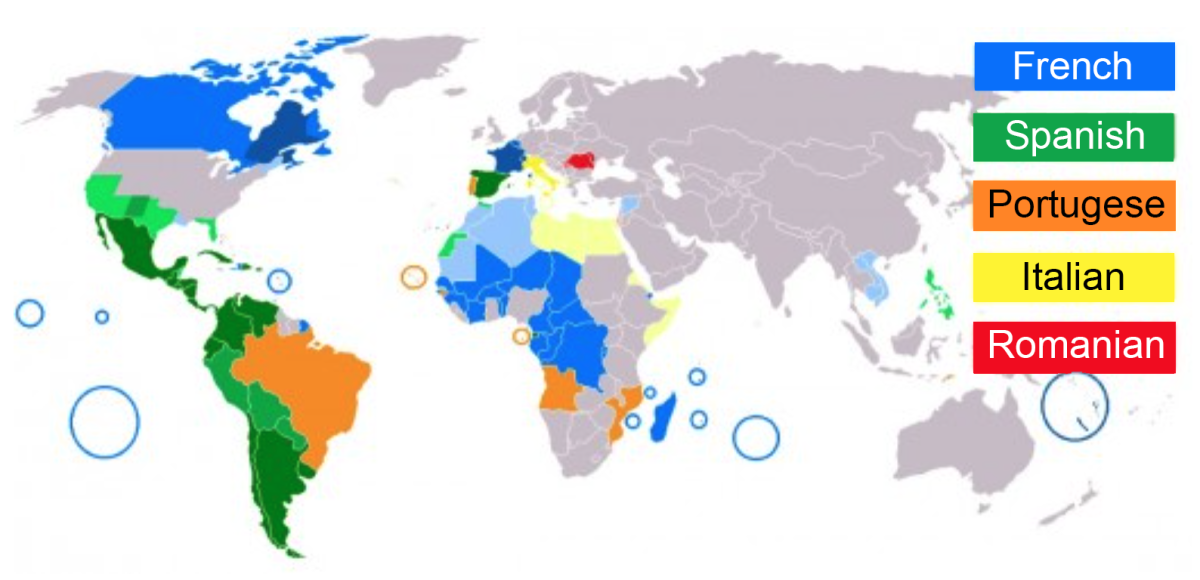

English was first introduced in the Philippines soon after Americans replaced the Spanish in the aftermath of revolution in 1898. Almost immediately, American Thomasite missionaries touched down to spread Christianity where the Spanish had left off. They were aided in their efforts by US soldiers, who were instructed to educate the islands as a matter of military policy. The use of English during this initial colonial period was considered a civilizing force for the natives, and was therefore the only accepted language in formal education as established by the US. The system begun by the Americans was the first national education system created across the Philippines. English was immediately taught and quickly absorbed, originally so that Filipinos could read the Bible, and later so that natives could take part in American educational resources and methods. Within a few short years, American teachers had passed on their vocation to native teachers, who took over the reins of English education. Post WWII, the need to develop the education system took on heightened importance for the US. General Douglas McArthur stated in his address to UNESCO in 1953 that “The matter of public education is so closely allied to the exercise of military force in the islands that in my annual report I treated the matter as a military subject and suggested a rapid extension of educational facilities as an exclusively military measure.” English developed wider and more consequential implications in Filipino society and was suddenly set at higher standards of English language knowledge as well as Anglo-American culture (Bautista, 246). The Spanish influence, from just after Magellan’s stop on the Philippines in 1521 all the way up to American introduction in 1898, underwent a vigorous campaign by the US to erase Spanish traces. Three hundred years of religious oppression by Spain’s Catholic Church left Filipinos eager to gain independence. In the short window between American foothold and the exit of the Spanish, Filipino literature, long shunned from recognition, began to flourish. It would be stemmed again only for the four decades of American colonization, before returning to its former glory by the mid 1970’s. While the Spanish had begun documenting the native languages as early as the late sixteenth century in order to translate the Bible into a known language, the Americans took little initial interest in local speech and instead taught the subject of English almost exclusively in grade schools. This is partly due to their effort to establish themselves as the new power in Spain’s stead, but was also intended to bring Filipinos into the American economy as rural workers (Bautista, 247). Decades later, with the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, relocating to the US has become a profitable possibility mostly for city dwellers and workers of highly educated trades (Nero, 264).

Spanish Terms: Place Names and Surnames

The extent of three centuries worth of Spanish traces is clear in the language, names, and place names of the Philippines. Hundreds of Spanish words were borrowed by local Philippine languages, but Spanish itself was not widely learned throughout the islands. Concentrations of Spanish presence and slave trade did result in the development of small pockets of Spanish creoles, but the standard language of Spain was not widespread itself (Lipski, 197). By the end of the Spanish occupation, Spanish was spoken by only two percent of the population (Bautista, 131). Terms from Spanish lexicon are seen in many of the Philippine languages, as well as the use of some suffixes for their Spanish meaning. The words abaca, to mean ‘Manila hemp,’ abeja to mean ‘bee,’ alegria to mean ‘joy,’ and zacate meaning ‘grass’ are all examples of this. Many such words of Spanish origin have also made their way into Philippine English (Bautista, 179). Media and television will often speak English while using occasional English and Spanish words that have come to be borrowed into the language, as well as some Chinese words (Bautista, 184). Americans living on the islands inevitably tended to borrow Philippine words to use within English sentences as well. One example of this is located in a journal entry: “In evening a strong wind prevails. Rains at10pm, baguio is blowing” (Bautista, 179). The word ‘despedida’ is used to mean a guest worker who goes abroad, from the Spanish word meaning a farewell party. From Chinese, Filipino speakers have borrowed the word ‘feng shui’ among others (Bautista, 184).

Academic English

English’s extent in Philippine schools is vast. Any Filipino teachers who major in English soon go on to teach English as a second language to students. It was the rule to immerse all Filipino students in English for their entire school career in all subjects. The students proved rapid learners, but, in practical application began using English in everyday life along with their native language. The exposure of English to the entire country, under varying degrees of teaching quality, caused English to be used in any situation, and therefore, changed and utilized to fit local needs. English was made the prestige language of business, education, and high-paying jobs (Nero, 262). The adaptation of American English to suit local languages was not considered to be appropriate use of the language. General American English, which tends only to be taught perfectly by small, exclusive, and expensive schools of large urban areas with significant access to resources and American teachers, is considered the only prestige version of English. It is the version printed in all the textbooks and technical workbooks that are available. The problem with this standard is that not everyone has access to these exclusive schools where General American English is taught; most people experience only the local form of Philippine English, which is somewhat different than the standard variety in its use of lexical terms, prepositions, stress, and also article use (Bautista, 75). This makes the educational system of the Philippines more an indicator of English language mastery than academic ability, which accounts for the large numbers of workers eager to take part in the export-driven economy. Many of these workers end up in Hong Kong, the Middle East, or Taiwan, as entertainers, construction workers, and sometimes as domestic helpers. Yet another special term for guest workers is ‘pensionadoes,’ from the Spanish. It is used to refer to the select group of Filipinos who are sent abroad to study government (Bautista, 76).

English Education's Effect on Spoken Language

The methods used to teach up until the 1950’s were oral-aural in nature. Students were immersed in the language and prompted to memorize blocks of text daily. This resulted in students who learned to mimic the language they saw without learning the mechanics of what they were reading. It was believed that the flow and comprehensiveness of sentences would present itself for understanding if the learner was only exposed to it (Bautista, 275). Semesters of studying celebrated English writers, such as Longfellow and Shakespeare, allowed them to acquire a highly bookish and in many cases old-fashioned form of English. This is a main reason why Philippine English has a very academic sound; being taught that the texts in the books are Standard English, they speak with this written dialect even in everyday situations (Bautista, 280). More recent techniques of ESL involve a wider array of mediums, such as visual aids, grammar introduction, listening, and reading instruction. For the vast majority of students, English is actually not their second language, but their third or fourth, so the problem is not in becoming bilingual but in being presented with enough exposure to master the new language. In 1974 the Philippine Bilingual Education Policy took a more active stance on introducing Philippine languages into education. It was decided not that English would be immediately removed, but that it should instead just not be immediately administered. The policy stated that the use of vernacular languages (or Filipino) for instruction was acceptable in grades one and two, but that in grades three and beyond the language of instruction must be English (Bautista, 276). As the prestige language, English is associated with ‘nation-building’ and ‘development’ particularly because the country’s economy of international capital is labor-intensive and export driven. This makes English even more important in the minds of the people, who use mastery of the language to move up in social and educational power. Over the past three decades English has been increasingly used among the poor, who compose the overwhelming majority of the population, in order to increase their standing and find higher positions (Bautista, 74). With developments in sociolinguistics over the past few decades, awareness between the formal and informal dialects is increasing, and students are more likely to understand the difference between the spoken and written dialects of English, as well as their relationship to yet a separate dialect: the Philippine version of English. The structure of Philippine English is being considered for its innovation and distinct form, rather than its deviation from Standard American English (Bautista, 280).

PE as a Living Language

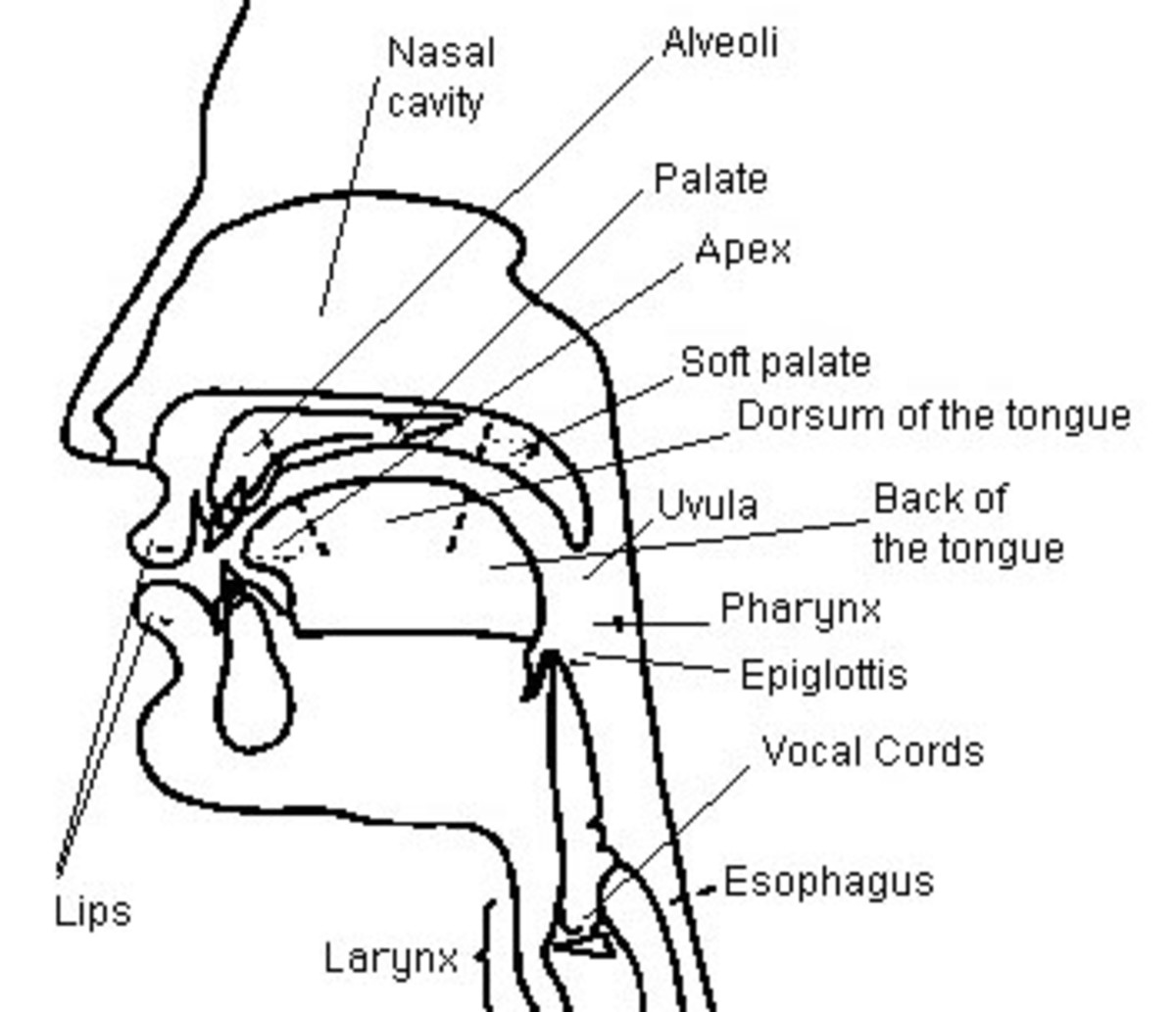

Attributes of Philippine English that distinguish it from other Englishes are parts of its lexicon, phonology, and syntax, as well as the stress with which it is spoken. Due to the Austronesian languages of the Philippines, which are often syllable-timed with clearly articulated syllables and fully annunciated vowels, Philippine speakers will tend to slow English down in order to understand it. Because of this difference, speakers might vary from native American speakers in speed of speech, de-stressing vowels, and un-stressing syllables. They may also fail to see the difference between long and short vowel sounds in such English words, such as the pairs ‘pool,’ and ‘pull,’ or even ‘-ty,’ and ‘-teen’ (Bautista, 274). It is a principle of linguistics that all languages are in a constant experience of change. The most susceptible aspect of change is vocabulary, followed by syntax, and followed last by phonology, the most resistant aspect (Bautista, 133).

Expansion, Borrowing, Spelling Change, Omission, Code-Switching

Normal expansion takes place occasionally with popular brand names, such as the use of the word ‘Colgate’ for any type of toothpaste. This is a reciprocal situation to the American expansion of the word ‘Kleenex,’ to mean any brand of tissue. There is some preservation of sounds lost to General American English that Philippine English manages to borrow for modern speech. These include the Shakespearean ‘wherein’ and ‘by and by.’ Coinage of new words from existing words is also a useful way to name previously unnamed ideas or things. The word ‘actor’ can be replaced with ‘actorist’ in Philippine English, and ‘doctoral’ can be used to mean ‘like a medical doctor,’ or ‘medicinal.’ Borrowing is also a common method of new lexicon entries. The word ‘despedida’ is borrowed from Spanish and the word ‘chocolate’ is borrowed unaltered from English (Bautista, 281). Some words in Philippine English are only different than GAE because of a change in spelling. Examples of this include bingo spelled ‘bingo,’ chemical spelled ‘kemikal,’ fake spelled ‘peke,’ and candy spelled ‘kendi.’ Meaning shifts take place as well. While GAE speakers may say ‘missus,’ meaning ‘the wife,’ PE goes a step further and also uses the word ‘mister,’ to mean ‘husband.’ The GAE word ‘tricycle’ has shifted to mean a pedicab, and the word ‘barrel,’ (spelled ‘baril’) is used to refer to a gun (Bautista, 146). Even the Filipino language itself has many words borrowed straight from English that Filipino speakers are expected to understand. On the educational television channel for children, (KTV), the following words were all used in the midst of Filipino: ‘championship,’ ‘energy,’ ‘hydrogen,’ ‘rap,’ ‘radiation,’ ‘video,’ and ‘water vapor’ (Bautista, 147). Another alteration, which does not take place in American or British English, but only in Philippine English, includes the omission of the articles ‘a’ or ‘the’ when using the word ‘majority.’ The following sentence would be considered standard Philippine English: ‘Majority of public school teachers oppose merit pay’ (Bautista, 204). The use of the word ‘such,’ also has a Philippine peculiarity. In GAE, ‘such’ is always followed by an article and a count noun or by a mass noun alone. An American can say ‘such a mistake…’ or ‘such folly…’ In PE, ‘such’ will never be followed by an article, but only by the noun, whether it is mass or count. The Filipino speaker can say ‘In the case of an approved absence, the event is recorded, but such absence is not counted toward excess.’ The use of ‘such’ without an article is an example of over-simplification, which is yet another attribute of Filipino originality in adopting English and making it their own. Code-switching of the word ‘na’ for ‘wherein’ will occur in both speech and writing. An example of this is: ‘Will it be some kind of lovers’ quarrel na after a short period they have come to an agreement’ (Bautista, 207)?

PE Pronunciation and Usage

Phonetic sounds can vary to a relatively small degree between PE and GAE. Consonant sounds of American English that cannot be found in most Philippine languages are ‘f’ and ‘v.’ This causes most Filipinos to pronounce words with these letters in a novel way: by replacing these sounds with ‘p’ and ‘b.’ All Philippine languages share these letters with American English: p, b, t, d, k, g, m, n, ñ, l, w, and y. The pronunciation of any of English’s six sibilants can cause difficulty for the Filipino speaker. Most Philippine languages possess only the ‘s’ sound, while American English uses s, z, sh, z as in seizure, ch, and j. There is one Sociolect variety of Philippine English that does include all six of these sibilants, and that is the Acrolect variety, which contains languages spoken by the majority, such as Filipino (Nero, 266). Vowels are found to have considerable differences among the various dialects as well. The Acrolect and Mesolect dialects contain a, e, i, o, and u, as well as the diphthong ey, which is pronounced as the American ‘e’ sound in the word ‘bait.’ The Basilect variety on the other hand has only the vowel sounds a, i, and u. General English unlike, Austronesian languages, also uses short and open vowel sounds, such as the ‘o’ sound in ‘bought,’ and the ‘a’ in ‘battle,’ which all three Philippine dialects replace with the long ‘o’ sound in ‘boat,’ and the long ‘a’ sound of ‘bottle.’ Intonation differences include General American English’s final rising-falling intonation in statements and final rising intonation in questions versus many of the Philippine languages’ tendency to fall in intonation at the end of questions. There are many differences in stress that also occur because Philippine speakers follow the rules of local languages when speaking English. The words ‘colleague,’ ‘govern,’ ‘menu,’ and ‘precinct’ are all first syllable-stressed in American English, but second syllable-stressed in Philippine English. The words ‘committee,’ ‘dioxide,’ ‘utensil,’ and ‘percentage’ are all second syllable-stressed in American English as well as for Acrolect and Mesolect speakers of Philippine English, but are first syllable-stressed for Basilect speakers (Nero, 267). Some lexical terms used interchangeably in Philippine English are ‘come’ and ‘go,’ ‘bring’ and ‘take,’ ‘open’ and ‘turn on,’ and ‘close’ and ‘turn off.’ A Filipino speaker may say ‘close the radio,’ and ‘go over to where I am.’ Philippine English considers some nouns as count nouns that American speakers would use as mass nouns. This causes differences between the two Englishes in subject-verb agreement. The prepositional phrase ‘problems of’ in the following sentence is an example of a plural noun behaving as singular: ‘Liquidity problems of rural banks on a massive scale is being experienced for the first time’ (Nero, 269). This difference in count versus mass nouns is also apparent with the use or non-use of articles: ‘The president directed Cargetano to give him a feedback on the matter.’ Prepositional discrepancies are the interchanges of ‘in’ and ‘to,’ ‘in’ and ‘on,’ ‘of’ and ‘to,’ and ‘up with’ and ‘up’ (Nero, 271). Examples of this are ‘I am ashamed to you that I missed your party,’ ‘to go up’ someone meaning ‘to go up to’ them, and ‘throw out’ to mean ‘throw up’ (Cruz, 54). There is also some deviation in Philippine English’s word order from that of general English, particularly when dealing with adverbs of time: ‘Solicitor General Ricardo yesterday said…’ Transitive verbs in American English are sometimes intransitive in Philippine English. These sentences illustrate the rule: ‘Did you enjoy?’ ‘I can’t afford.’ ‘I don’t like’ (Nero, 273).

In Conclusion... The Future of PE

A 2003 study conducted by Thelma Jambalos found that different generations of Filipinos tended to vary widely in their use of Philippine English (Gonzalez, 31). The older the generation, the more deviant was their form of English from the general American standard. The oldest generation studied (aged 70-94) had the fewest vocabulary errors and the best sense of writing skills. However, the most recent generation studied (aged 12-22) was shown to have more standard American intonation and stress patterns, mastery of the short ‘a’ sound, improvement in mastery of consonantal clusters, and less tendency to interchange sibilant ‘s’ for ‘z’ (Gonzalez, 41). This suggests that the Philippine teachers, traditionally teaching English with Austronesian patterns and intonations, have begun to learn a more American way of speaking, and also that students have more exposure to American English than in the past, thanks to media, television, and internet.

It is unlikely though, that this shift will continue rapidly because eighty percent of the population, (below the poverty line) is not exposed to most of these influences on a daily basis. They will continue to speak and teach the Philippine form of English. As one of the two official languages of the country, the other being English, ‘Tagalog’ is currently spoken by over fifty percent of the total population, either as a first or second language. As early as 1935 when it was decided that the Philippines should have a national language based on the existing native languages, Tagalog was the main language considered (Bautista, 143). Tagalog, with elements borrowed from other Philippine languages, Spanish, and English developed as the official native language. In 1959 it was renamed ‘Pilipino,’ and in 1973 the name was changed again to ‘Filipino.’ In further efforts to promote nationalism, the first monolingual dictionary of a Philippine language was finally produced in 1989. This dictionary has had little impact however, because the vast majority of public schools across the islands are unable to purchase the dictionaries. Because of this, it is unlikely that a dictionary will replace the traditional method of word of mouth as the source of national language formation. It is more likely that local conditions will continue to affect both Filipino and English, just as they have for the past century. Borrowing remains a heavy influence on both languages, with thirty percent of Filipino words borrowed from Spanish, Malay, Chinese, and English, and the use of many Tagalog words in Philippine English to create the portmanteau of ‘Taglish’ (Bautista, 189).

Philippine English was first studied as a distinct branch of English in 1969, when characteristics such as ‘Filipinisms’ and the use of ‘Taglish’ and ‘Engo’ were first labeled and discussed in detail (Bautista, 201). As with any transplanted language, the preferred focus is on its local innovation as a distinct form of English, and not its deviation (Nero, 280). The use of English in schools, though it exposed the islands to democracy via the literature of Henry Longfellow, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Paine, and the pro-colonial themes of ‘Evangeline,’ and ‘The Song of Hiawatha,’ looks likely to remain the language of education in the future and to foster the continuing development of Philippine English within the country (Bautista, 248). The situation is neatly stated by a Filipino poet: “English is now ours. We have colonized it too” (Nero, 77).

____________________________________________________

Sources

Bautista, Maria Lourdes S. Philippine English: linguistic and literary perspectives. Hong Kong University Press. Hong Kong, 2008.

Cruz, Isagani R. A dictionary of Philippine English. Anvil Publishing, Inc. Pasig City, 1995.

Gonzalez, Andrew B. Three Studies on Philippine English across generations: towards an integration and some implications. Linguistic Society of the Philippines. Manila, 2003.

Lipski, John M. New thoughts on the origins of Zamboangueno (Philippine Creole Spanish). Language Sciences. Elsevier Science, Ltd. University of New Mexico, 1993.

Nero, Shondel J. Dialects, Englishes, Creoles, and education. Lawrence Erlbaum Publishing.