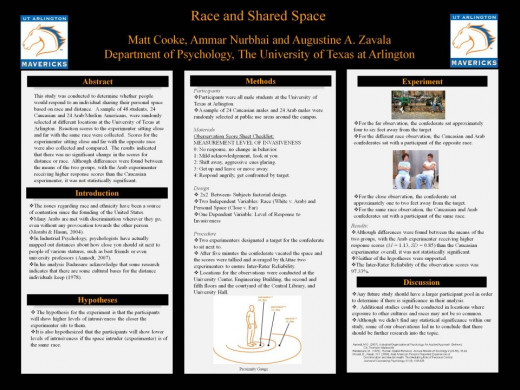

Race and Shared Public Space

How does race affect shared space?

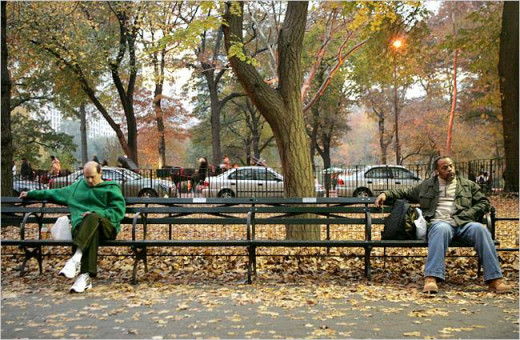

America has been seen as a country where individuals can come here, work hard, and depending on the level of effort, expect to be fruitful and prosperous. However, becoming a member of our society hasn’t meant that Americans will welcome you with open arms. Certain events within our nation’s history have served to mobilize the population against certain enemies to the U.S. like the Nazis, Communists, and Osama Bin Laden. However, these events have also served to fan the flame of racism, from the internment of the Japanese during WW II to the killings and harassment of immigrants post 9/11. These issues have been debated on a macro level, but what about the micro level? How does an individual's perception of race affect the non verbal cues while sharing public space? If individuals of another race decide to share a bench in a public setting, will they demonstrate a certain level of discomfort?

Are the rules of sharing space and keeping distance culturally or biologically determined?

Badassare (1978) found that “spatial behavior is no more a cultural trait than it is a biological instinct, since individuals adjust their personal distances based on new contingencies” (p.35). In his analysis Badassare acknowledge that some research indicates that there are some cultural bases for the distance individuals keep, but that the findings are weak at best. One of his theories that individuals control or minimize contact in close encounters is what he called “specialized withdrawal”. The theory stipulates that people work to conserve energy by avoiding neutral and harmful interactions and focus on the positive ones (p.42). Over time the individual learns to avoid interactions that cause social overload and cognitive fatigue. Individuals reacting to an unknown individual sitting next to them may have had a negative experience with an in individual resembling the stranger, so they react to remove themselves from a possible interaction.

Are you comfortable with strangers in your intimate space?

Animosity and passive aggression

Bushman & Bonacci (2004) examined the effects of discrimination against Arabs. In the experiment they recruited 512 college students and had them answer a battery of questionnaires about participating in unsolicited email, mail and phone studies. Answering yes to the email study was considered voluntary consent. The participants then answered surveys to measure their level of prejudice about certain minority groups; individuals selected were white, non Latino and who scored high on the Arab American prejudice score. The participants received a “lost” email addressed to an Arab surnamed individual, and one from a European surnamed individual. The returned emails were documented, and the final totals were verified. The results indicated that these individuals were less likely to forward the lost scholarship email to an Arab surnamed individual than a European surnamed individual. The authors concluded that “Because the government and civil rights organizations urge tolerance towards Arabs, prejudiced individuals may use less visible forms of discrimination to harm Arabs” (p.757). Individuals who harbor animosity towards a minority “out-group” may use passive aggressive means to perpetuate their attitudes. They may get up and leave an area if an “undesirable’ minority attempts to share their public space.

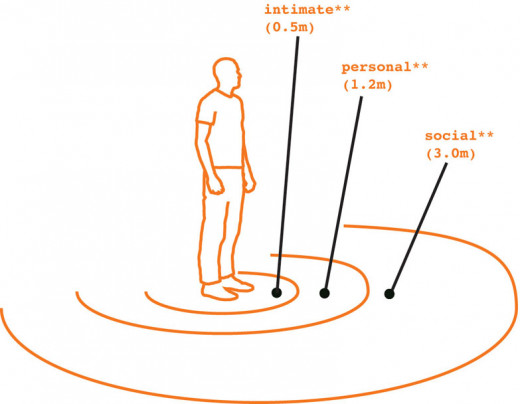

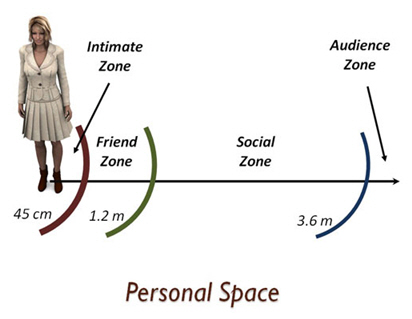

Eye contact and distance

Pederson & Shears (1973) reviewed different system theories in relation to personal space. One variable noted from their research is eye contact. They found that “the perceived distance between people could be shortened or lengthened by looking at them or away from them” (P.376). They saw eye contact as a way to gauge the friendliness of an individual sharing a public space. In review of another study, results indicated that spacing would determine the length of stay in a shared public space. Individuals who violated norms associated with intimate spacing would cause the other person to get up and withdrawal. Eye contact and especially spacing will be a factor in our experiment to gauge the comfort levels of individuals we sit next to.

Reactions to physical closeness

Storms & Thomas (1977) researched the reactions to physical closeness. They conducted three experiments to measure the effects physical closeness using male participants. The participants were 149 male students who were attending the University of Kansas. In the first experiment the participants with similar or dissimilar attitudes sat at a normal and close distance from each other. The second experiment and third experiments were conducted using the same distances as the first, except the experimenter acted in a hostile or friendly matter. The results indicated the person who was friendly and had similar views was liked more and was able to sit closer to the participants longer than the group who was dissimilar, disliked and sat closer (p.416). The main variable of interest seemed to be the friendliness of the individual who was sitting next to the participants. In our experiment, we will not overtly interact with the participants, but the perceived similarities of our experimenter could be a factor in our experiment.

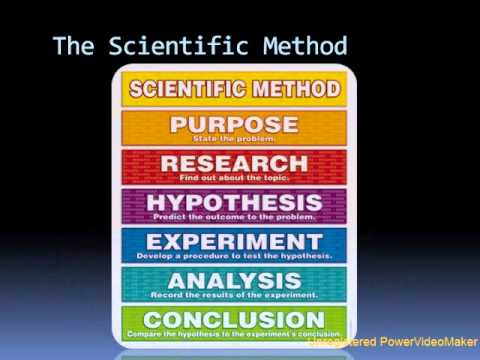

The experiment

In our experiment we want to investigate whether race and distance in a public space will affect a response from our participants. We hypothesize that sitting close to an individual in a public setting will elicit a response. We also hypothesize that a white participant will display a more negative response to the Arab experimenter than to the White experimenter. People who may have a race bias will move away or be less likely to share public space with someone of a different race.

Participants

Participants were male students at the University of Texas at Arlington. A sample of 24 Caucasian males and 24 Arab/Muslim males were randomly selected at public use areas around the campus. The control groups measured responses to same race/distance and same race/distance + interaction. The experimental groups measured responses to different race/distance and different race/distance + interaction.

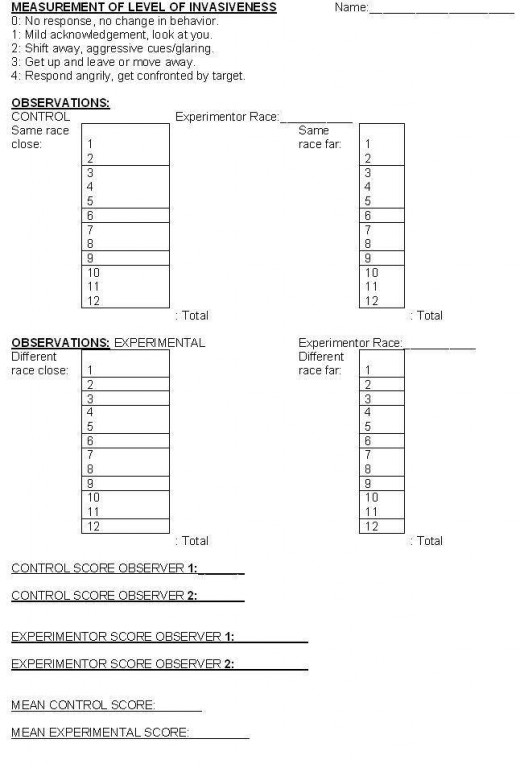

Materials

An observation checklist was created to measure the level of response that the target had to sharing space with a stranger. The measurement of invasiveness ranged from 0 – 4, with a 0= no response or acknowledgement, 1= mild acknowledgment, 2= shift away/ aggressive cues/ glaring, 3= get up and leave and 4= angry response, being confronted by target.

Design

The design is a 2x2 factorial measuring responses to space distance (close and far), race (different vs. same) and the interaction between race and space. The two independent variables were race and space with the dependent variable being the level of response to sharing the same space.

Procedure

The experimenter would designate a target for the confederate to sit next to based on the space and race. The observations were made, and then the response measurements were added and averaged to compute the final score. The same race close group response was measured by gauging the level of response of the confederate sitting within two feet of the target. After five minutes the confederate would vacate the space and the observations scores were tallied. The same race far group had the confederate sit approximately four to six feet away from the target, record response if any, then repeat the same withdrawal from the area procedure. The procedures for different race close/far followed the same protocol except the targets were the opposite race than the confederate. The locations where the observations were conducted were the University Center food court and the common areas on the first and second floors. The study areas between the 2nd and 5th floors of the Central Library, and the common grounds located in front of the library, and the first floor of University Hall.

Results

To compute the results, a 2x2 factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with two Independent Variables and one Dependent Variable. Although differences were found between the means of the two groups, with the Arab experimenter receiving higher response scores than the Caucasian experimenter, it was not statistically significant. Furthermore, there was no main effect of either variable and no interaction effect either. Our hypothesis, that people of Arab descent sharing an individual’s personal space, more specifically Caucasian, would be met with more hostility, was not supported either.

Discussion

The results of our experiment didn’t yield any significant results. This may be due to the sample size being only 48 participants. Any future study should have a larger participant pool in order to determine if there is significance in their analysis. Another confound in our study were the number of locations where the observations took place. To control for experimenter effects, we initiated our observations around different parts of campus at UTA. This was done so that the observers wouldn’t draw attention to themselves as the experiment was being conducted. However, by choosing different locations, we had less control of the participants in the study. An individual in the food court may spend less time there than someone studying in the library. The study was conducted between male participants of Caucasian and Arab/Muslim populations. Any future studies may include both males and females; this could increase the participant pool and measure multiple interactions between race and gender.

Dixon (2001) sought to look at the contact hypothesis as it relates to spatial organization of intergroup relations. The contact hypothesis proposed that regular interaction between different groups reduced intergroup prejudice, if it happens under ideal circumstances (Allport 1954). In his book, Allport designated 4 conditions in which this can occur. First, participants must be of equal status, second they shouldn’t be in competition with each other, third they should attain common goals interdependently and finally their contact should be supported by local authorities/institutions (p.590). Dixon points those attitudes towards race could change once there is more exposure and observation of the customs of the out-group race. Diversity programs on campus and in the community could have reduced the social discomfort and animosity towards a certain races, like the Arab Americans. Another study could be conducted in a location where exposure to other cultures and races may not be so common, like a shopping mall, bowling ally, and any other off campus location. Although we didn’t find any statistical significance within our study, some of our observations led us to conclude that there should be further research into the topic.

© 2008 Augustine A. Zavala

References

Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Baldassare, M. (1978). Human Spatial Behavior. Annual Review of Sociology 4 (29-56), 35,42.

Bushman, B.J. & Bonacci, M.A. (2004). You’ve got mail: Using e-mail to examine the effects of prejudice attitudes on discrimination against Arabs. Journal of Experimental Psychology 40, (2), 757.

Dixon, J. (2001). Contact and Boundaries. Theory & Psychology 11 (5), 596.

Pederson, D. M. & Shears, L.M. (1973). A review of Personal Space Research in the Framework of General System Theory. Psychology Bulletin 80 (5), 376.

Storms, M. & Thomas, G.C. (1977). Reactions to Physical Closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35 (6), 416.