Reading Fluency - A Review of Literature

Introduction

In order for students to develop fluency in reading, teachers must incorporate a variety of interactive fluency activities (Oakley, 2005; Welsch, 2006). Though fluency has been recognized as an important aspect of reading, it is very rarely an expressed goal of reading instruction (Rasinski, 1989). By monitoring student progress with informal assessments of fluency and word recognition, instructors will be able to provide students with immediate feedback and guidance to help students progress in this critical area (Cowen, 2003). Using a variety of classroom fluency strategies, teachers can develop fluency for everyone, bringing each student closer to balanced literacy.

Reading Fluency

Reading fluency has a plethora of definitions. It has been defined as smooth effortless reading, precise and speedy reading, and steady and natural oral production of written texts (Oakly, 2005; Rasinski, 1989; Welsch; 2006). In actuality, reading fluency is made up of many components. Speed, accuracy, automaticity, appropriate phrasing, and even expressiveness are all characteristics of fluent reading (Oakley, 2005).

In addition, researchers have stated that the above definition is incomplete without appropriate consideration for the role of comprehension (Oakley, 2005; Stahl & Heubach, 2005). One of the five goals of fluency oriented reading instruction incorporates comprehension: “Lessons will be comprehension oriented, even when smooth and fluent oral reading is being emphasized” (Stahl & Heubach, 2005, p. 30). Consequently, it is natural for activities designed to develop fluency to result in improved comprehension, because a fast pace in reading allows the short term memory to retain words long enough to create meaning (Oakley, 2005). A stress on comprehension also improves word recognition, which is another necessary component of fluency (Stahl & Heubach, 2005).

Oakley (2005) provided a comprehensive definition of reading fluency based on the outcome of interactive reading processes:

Oral and/or silent reading fluency results when a reader can successfully engage,

integrate and self-monitor a repertoire of interactive reading competencies,

including automaticity of word recognition, appropriate reading rate, smoothness,

phrasing, expression and comprehension. Reading fluency involves the strategic

use of graphophonic, syntactic/grammatical, semantic knowledge. (p. 14)

The Importance of Reading Fluency

Fluency is an essential component of reading. Included in the five literacy areas is one whole section devoted to fluency (Cowen, 2003). Fluency is a foundation of proficient reading (Hiebert & Fisher, 2005). According to Hiebert & Fisher, “Once decoding becomes automatic, readers can devote their attention to comprehending text” (2005, p. 444). Additionally, the strong link between fluency and comprehension is another reason to consider teaching fluency lessons, especially fluency explicit lessons (Oakley, 2005).

Another important aspect of fluency is its role in the six stages of reading ability (Stahl & Heubach, 2005). Confirmation and fluency are both components of the third stage, in which students “learn to decode words fluently and accurately and to orchestrate the use of syntactic and semantic information in text to confirm word recognition” (Stahl & Heubach, 2005, p. 27). Without fluency, students are at risk of never reaching the subsequent stages, where students learn by reading and grow as individuals through their knowledge, and apply what they have read to the world.

Perhaps a more important reason to develop fluency in reading is the aesthetic and motivational aspects that come along with fluency improvement. According to Oakley, “fluent readers tend to enjoy reading more, have more positive attitudes toward reading and a more positive concept of themselves as readers than do less fluent readers” (2005, p. 15). In short, when fluency is attained, reading becomes a fun pastime, which leads to more time spent reading, which results in additional growth in fluency.

Assessing Reading Fluency

The Oral Reading Fluency Rating Scale is a comprehensive tool for assessing reading fluency (Oakley, 2005). The scale measures three aspects of fluency, accurate decoding of words, automatic decoding of words, and prosody, or “the appropriate use of phrasing and expression to convey meaning” (Oakley, 2005, p. 19). Identifying the characteristics of non-fluent readers is also valuable, because it allows teachers to focus on the aspects of fluency that the reader is struggling with the most. When non-fluent readers are categorized, teachers can focus on choosing the strategies to help students improve (Oakley, 2005).

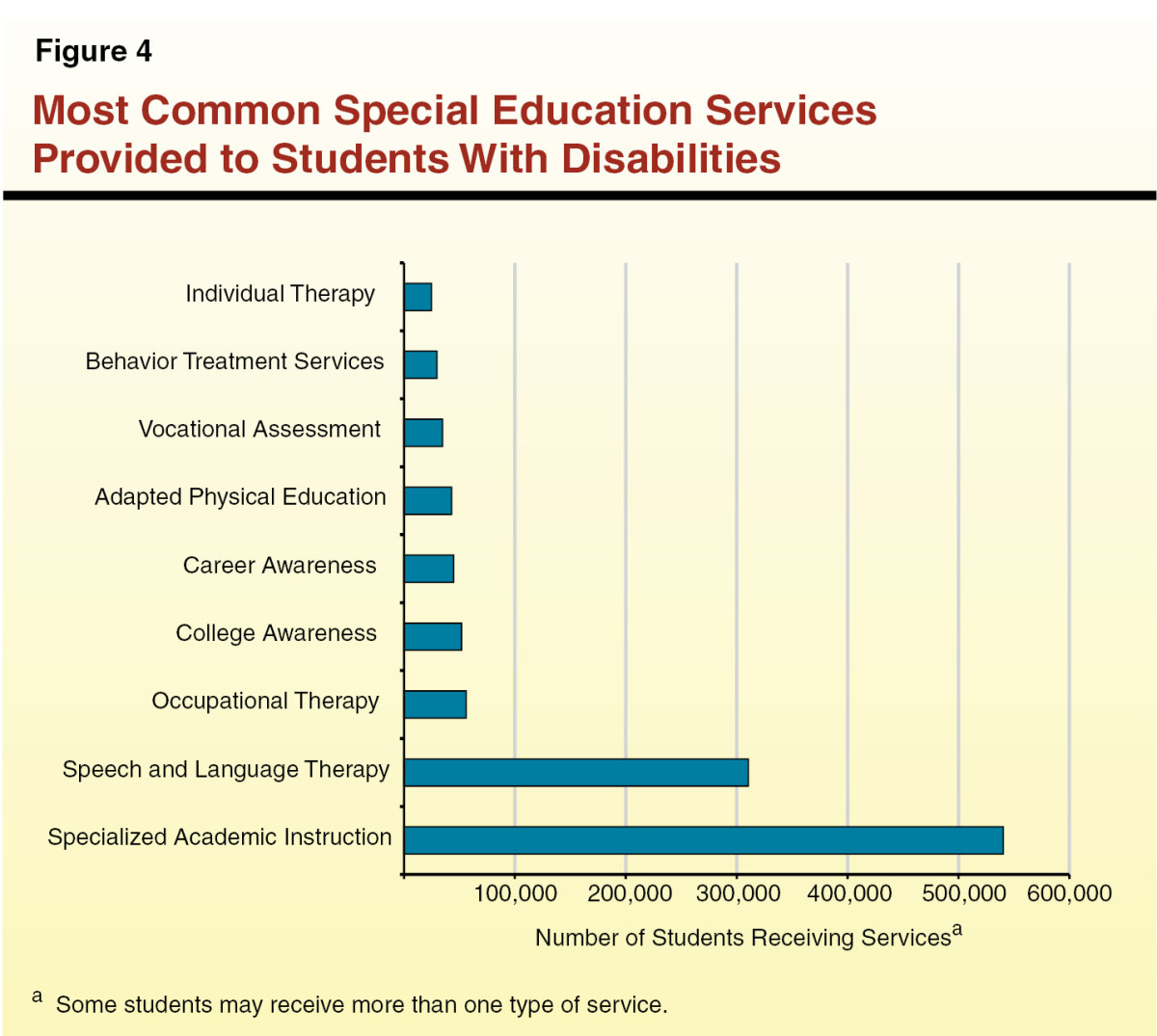

According to Oakley, there are at least 4 categories of non-fluent readers. The first category is called non-fluent struggling. “These readers struggle in all areas: accuracy, comprehension and rate” (Oakley, 2005, p. 17). Non-fluent struggling children need help with self monitoring, graphophonics, semantics, syntactic and strategic areas. Oakley refers to the second category of non-fluent readers as non-fluent competent. These readers mainly need help in self monitoring. They have achieved a decent amount of accuracy, comprehension and rate.

Another category of non-fluent readers is called non-fluent low accuracy (Oakley, 2005). These are the readers that manage to make meaning even though they lack accuracy of word recognition. These students need help with sight words and some graphophonic techniques. Many fluency strategies would probably help readers in this category. The last category of non-fluent readers is called non-fluent low comprehension. “These readers have reasonable word recognition skills but low comprehension” (Oakley, 2005, p. 17). Incorporating comprehension strategies into fluency instruction would be very beneficial to students in this category.Developing Reading Fluency

There are many activities and strategies to develop both oral and non-oral reading fluency. The first step in designing a fluency lesson is to choose a piece of literature with an appropriate level of readability (Hiebert & Fisher, 2005; Oakley, 2005; Rasinski, 1989; Stahl & Heubach, 2005; Welsch, 2006). Rhythmic, predictable, and repetitious literature has been found to aid fluency (Welsch, 2006). Challenging texts are more appropriate for lessons on concepts and vocabulary, while the easier texts, which can be read with a high accuracy rate of 90%-95% or more, are ideal for fluency development (Oakley, 2005; Welsch, 2006). This can make choosing the literature challenging, because many easy texts might be considered boring to read. For this reason, it is beneficial to allow the students to determine their own readability level and choose the texts, to avoid using boring or frustrating texts (Oakley, 2005; Rasinski, 1989).

According to Clark, “Readers must be able to monitor their own oral reading in order to learn to read aloud with appropriate expression” (Oakley, 2005, p. 16). Once students attain self monitoring through explicit teaching and feedback, repeated reading with a model, such as the teacher, a proficient peer, or a tape recording, can be used to develop fluency (Welsch, 2006).

Allowing students to preview texts beforehand is another important fluency strategy. Silent reading and rereading, paired reading, and read alouds are all good previewing practices to incorporate before oral reading is required (Welsch, 2006). Once the literature has been previewed, there are many whole class activities that can be used to develop fluency. Choral reading (reading aloud in unison) is one of the most popular whole class activities (Rasinski, 1989). Echo reading can also be done with the whole class (Welsch, 2006).

A newer activity that combines many concepts into one lesson is oral recitation (Oakley, 2005). This lesson has two components. First the teacher introduces the text through a read aloud. The class discusses the story and creates a story map. The students use the map to each create an individual summary of the story. After the summaries are written the teacher models fluency again by rereading the passage (echo or choral reading can be used here with easier texts). During the rereading there should be discussion on what the model is doing to show fluency. The second component of oral recitation is individual practice. Students practice the summaries that they created using a barely audible voice. After many rereads and practices, the students present their summary to the class (Oakley, 2005).

Readers’ theatre has also been found to aid fluency development (Oakley, 2005; Welsch, 2006). This activity includes plenty of rereading, and a performance style is often used and modeled, which greatly aids the expression characteristic of fluency. “Readers’ theatre provides an authentic reason to engage in repeated readings while providing a model of fluent reading” (Welsch, 2006, p. 182).

Paired reading, or partner reading, is another effective activity that can take the place of round robin reading (Stahl & Heubach, 2005). Students choose a partner and find a somewhat personal place. Then they take turns reading a passage, alternating paragraphs. The texts for partner reads can be anything, from the math text book, a book that was recently read to the students by the teacher, or a book that has been reread many times. Substituting partner reading for round robin during regular class time offers students more time to practice fluency and can even engage the students in their learning (Stahl & Heubach, 2005).

Feedback is a very important part of fluency instruction and will aid growth in reading fluency (Oakley, 2005; Rasinski, 1989; Welsch, 2006). Teachers should provide “the correct words when students read words incorrectly during oral reading. This can reduce the number of errors and, in turn, increase reading fluency” (Welsch, 2006, p. 182). Teachers don’t always have to provide the feedback. Computerized audio recordings can be used to assist children in analyzing their own and others’ performances (Oakley, 2005). Oakley provided visual waveforms to the students so they could see where they needed work on smoothness of speech. According to Oakley (2005), “…This additional feedback on their oral reading served as an extra context for discussion and thinking, and drew their attention to aspects of their reading that had not seemed worthy of comment through listening to the audio recordings” (p. 17).

Programs like Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) and Drop Everything And Read (DEAR) have debatable purposes in the classroom (Oakley, 2005). Though these programs are good for offering practice time, students first need to be somewhat fluent readers to get the full benefit from SSR and DEAR. This activity would be most beneficial to non-fluent readers if the right assistive technology is used (Oakley, 2005). Text-to-speech programs, such as CAST and eReader, are beneficial to struggling students, because these programs “help them read texts in a sustained, independent manner (although not silent)” (Oakley, 2005, p. 18). For a combined use in the classroom, proficient readers can be given SSR time while non-fluent readers are given time to work with text-to-speech assistive technology.

Conclusion

Fluency is an important component of literacy, and it can only be reached when students are given an adequate amount of explicit fluency instruction that is customized to individual needs. “To help non-fluent readers, teachers should try to ascertain where students’ difficulties lie and attempt to tailor instruction to these areas as well as using fluency strategies to help them ‘bring it together’” (Oakley, 2005, p. 20). By using these strategies, teachers will ensure that every student becomes fluent in reading. Teachers need to make reading fluency an expressed goal of reading instruction to ensure that every student reaches his or her potential in balanced literacy.

Bibliography

Cowen, J. E. (2003). A balanced approach to beginning reading instruction: A synthesis of six major U.S. research studies. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Hiebert, E. H. & Fisher, C. W. (2015). A review of the National Reading Panel’s studies on fluency: The role of text. The Elementary School Journal, 105 (5), 443-460.

Oakly, G. (2005). Reading fluency as an outcome of a repertoire of interactive reading competencies: How to teach it to different types of dysfluent readers (and how ICT can help). New England Reading Association Journal, 41 (1), 12-21.

Rasinski, T. V. (1989). Fluency for everyone: Incorporating fluency instruction in the classroom. The Reading Teacher, 42, 690-693.

Stahl, S. A. & Heubach, K. M. (2005). Fluency-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 37, 25-60.

Welsch, R. G. (2006). Increase oral reading fluency. Intervention in School and Clinic, 41 (3), 180-183.