At-Risk Youth and Residential Education (Boarding Schools and Wilderness Programs)

Poll

Are you a parent that is looking for more information on residential education for your child?

This study focuses on boarding schools, wilderness programs, brat camps, and military academies. As these institutions become more affordable, their popularity and enrollment rates increase; but, “little is known about the use of residential education programs in the United States. Even less is known about the use of residential education with foster youth or with other youth at risk of school failure” (Lee and Barth 2009: 156).

It is common in today’s society for parents with at risk youth to consider enrolling them in means of residential education, or newer types of therapeutic, residential education. By studying the types of institutions and their affects on adolescents, we can discover the benefits, disadvantages and variations of learning and living away from home.

Boarding schools were the first types of residential education in the U.S. Although they began as a way to prevent excessive transportation, they soon became elitist institutions, mainly located in the Northeast, as a way for upper class parents to assure that their child obtains a good education:

Boarding schools for youth in the U.S. are more than 250 years old. Although boarding schools are now typically conceived of as the exclusive domain of youth from wealthy families to receive an enriched academic living environment, there is longstanding and growing interest in adapting this model for less privileged youth. (Lee and Barth 2009: 158)

As Swanson and Schneider (1999) suggest, boarding schools bring opportunities to their students. Social mobility can result from these institutions through networking with likeminded individuals. Similarly, Goldsmith (2000) calls this era “the Renaissance of Boarding Schools,” because of the success that former students obtain from attending these institutions. Overall, boarding schools prove to be sufficient in motivating their students and maintaining strong school bonds (Swanson and Schneider 1999), yet, the effects on parental absence during adolescent years has yet to be researched thoroughly.

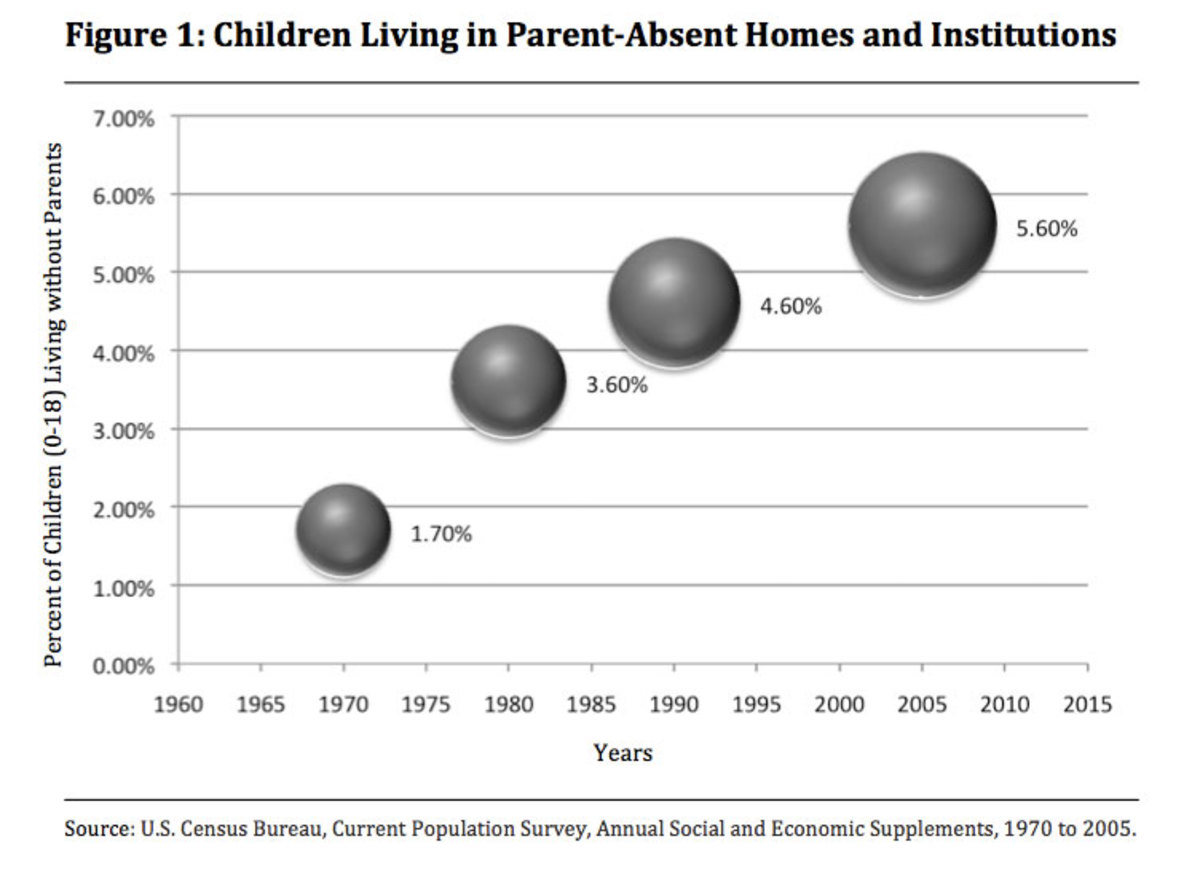

In 1981, 4.4% of teenagers ages 15 to 17 lived without their parents (Montemayor and Leigh 1982). The parental absence rates for all children (0 18 years of age) have also increased over the last few decades (see Figure 1). With the increasing popularity of boarding schools and other means of residential education, it is becoming more common for adolescents to spend their high school years at an institution as opposed to living at home with their families. It is important for our society to understand what changes occur after an adolescent lives away from home because it is more common for people to make use of the benefits residential education offers. Although these institutions have been proved to help students excel academically, we have to analyze what types of students benefit from this learning environment and which ones do not.

Parents often choose to enroll their child in residential for socialization:

Social connections help students form cohesive friendships with other students in the school. Friendship bonds are the solder that binds the upper class together into an interconnected series of power relationships that move beyond the school experience and often last through students’ business, political, and social lives. (Shane et. al. 2008)

Socialization is a clear benefit of residential education, yet, the type of living situation that the adolescent is placed into has an effect on their ability to socialize. If the type of living situation is vastly different than the lifestyle of the child before enrollment, they could return to their previous behavioral patterns, therefore erasing the effects of the program or programs (Rubin et. al. 2007). Through examining the types of living models that residential education provides, we are able to analyze whether the adolescent will be able to adapt to their new residence and how the lack of a family structure affects them.

As Sprott, Jenkins and Doob (2005) have proved, students with stronger school bonds are less likely to participate in at risk or violent behavior. Students with weak school bonds include those whose grades have declined and are not involved or engaged in their school’s programs. Residential education is a common solution for students with weak school bonds. Because residential education requires students to live at their school, students are able to engage themselves in sports, clubs and other extra curricular activities without having to travel.

Residential education can help those with behavioral issues create stronger school bonds, but can also cause some to feel isolated. A student needs to carefully and comfortably adjust to their new living situation in order to succeed in school. As other researchers have discovered (Newton, Litrownik, and Landsverk, 2000; Rubin et. al. 2007; Lee and Barth 2009), involuntary or instable placement into these programs can also cause the at risk adolescent to have poorer grades. Living situations have a direct correlation to how well a student can transition to living at a residential institution.

More and more, we see these institutions playing a major role in correcting at risk behavior (Dryfoos 1990). Wilderness programs are the most common choice of residential education for at risk youth (Romi and Kohan 2004). These programs require students to live outdoors and learn to be independent through basic survival techniques. While boarding schools sometimes attempt to create a family like environment for the student, wilderness programs and brat camps attempt to place the adolescent into a different environment than they are used to (Harper and Russell 2008). This change in environment can cause a culture shock, allowing the student to adjust to that lifestyle.

Generally, the students at wilderness programs will camp outdoors in order to separate them from society. By freeing students from their normal routines, wilderness programs attempt to rid students of their bad habits. “While allowing participants to experience the outdoors and build physical stamina, Adventure or Wilderness Programs (WP) also provided them with various life skills: planning abilities, teamwork, confronting stress situations, assuming personal responsibility, leading and being led in a group” (Romi and Kohan 2004: 115). This type of residential education focuses on correcting behavioral issues and strengthening independence, leaving academic achievement to other residential institutions. Wilderness programs have helped students socialize with others in a supervised, dependent setting. This type of living situation is so different from how adolescents generally live in the home, that they may have trouble adjusting to the environment once they return from the program.

According to the Coalition of Residential Education (CORE), which defines residential education as “an umbrella term for community like settings where at risk children live and learn together, outside their homes, within stable, supportive environments,” there are four types living models for residential education institutions. One type is a family style home, where a married couple lives with a group of students in a large home. Each student has their own living quarters or share them with another student, while the “house parents” live in a separate area of the home. This is a common living situation for students of small college preparatory academies and boarding schools. With a home like environment to live in, students are less likely to be at risk or struggle to achieve academically. As Lawton, Silverstein and Bengtston (1994) suggest, having a nuclear style family is beneficial to the development of an adolescent.

Another type of residential education living model is dormitory living. Similar to many college dormitories, this living situation requires a resident advisor to supervise the halls. In this living model, students have separate living quarters that they may share with other students but are able to speak with the resident hall advisor when faced with obstacles. While this model doesn’t encourage at-risk behavior, the lack of supervision and a family structure in this model can result in negative types of behavior. This is the most common type of residential education living model and is used in boarding schools, military academies and some brat camps.

At some institutions, dormitory and family style homes are both offered or mixed, depending on the student’s age or needs. This mixed model can help students correct behavioral problems, while allowing more freedom for students that maintain their grades. Although the students have parental figures close to their living spaces, they do not share a common area or share meals often. This can prevent them from maintaining a family dynamic that Lye (1996) discusses in her studies on parent absent adolescents.

A rare living model that can be found at very large boarding schools or military academies are dormitories with a shifting staff. Although this high security environment is generally safe, this model is not recommended for at risk youth because of the lack of attention an individual student gets from a resident hall advisor or parent like individual. Adolescents living away from their parents may feel very isolated. It is important for a residential institution to provide housing that maintains a sense of community in order to prevent at risk behavior. This study attempts to examine the factors of residential education that damage or strengthen the parent child relationship for students at these institutions.

Read More About the Child-Parent Relationship and Res. Ed.

- The Benefits and Disadvantages of Residential Education: Boarding Schools, Wilderness Programs, and

This hub describes the benefits and disadvantages of residential education, which includes boarding schools, military academies, wilderness programs and brat camps. - The Parent-Child Relationship: The Effects of Separation and Residential Education

The number of children living without their parents continues to grow each year. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2005), the number of parent absent children increased by 329% since 1970. This data is directly correlated to the rising popularity

Are you considering residential education for your child?

What type of institution are you considering?

Was this article helpful to making your decision?

References

Beker, J., and R. Feuerstein. (1991). Toward a common denominator in Effective Group Care Programming: The Concept of the Modifying Environment. Journal of Child and Youth Care Work, 7, 20-34.

Dryfoos, Joy G. (1990). Adolescents at Risk: Prevalence and Prevention. Oxford University Press.

Gerard, Jean M, and Cheryl Buehler. 1999. “Multiple Risk Factors in the Family Environment and Youth Problem Behaviors.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 61:343-361.

Hagaman, Jessica L., Alexandra L. Trout, M. Beth Chmelka, Ronald W. Thompson, and Robert Reid. 2009. “Risk Profiles of Children Entering Residential Care: A Cluster Analysis.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 19:525-535.

Harper, Nevin J, and Keith C Russell. 2008. “Family Involvement and Outcome in Adolescent Wilderness Treatment: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation.” International Journal of Child & Family Welfare 11:19-36.

Flint, Anthony. (1993). Boarding School Approach to Youths At Risk Questioned. Boston Globe, 23:64-86.

Goldsmith, Heidi. (2000). The Renaissance of Residential Education in the U.S. Conference Summary. Annual Review of Sociology, 22:79–102.

Lawton, L., M. Silverstein, and V. L. Bengtson. (1994). Solidarity between generations in families. Intergenerational Linkages: Hidden Connections in American Society, 19–42.

Lee, B. R. and R. P. Barth. (2009). Residential Education: An Emerging Resource for Improving Educational Outcomes for Youth in Foster Care? Children & Youth Services Review, 31, 155-160.

Lye, Diane N. (1996). Adult Child-Parent Relationships.University of Washington Press.

Newton, R. R., A. J. Litrownik, and J. A. Landsverk. (2000). Children and Youth in Foster Care: Disentangling the Relationship between Problem Behaviors and Number of Placements. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 1363-1374.

Sprott, J. B. B., Jenkins and Doob. (2005). The Importance of School: Protecting At-Risk Youth From Early Offending. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 3:1-59.

Romi, Sholmo and Ezequiel Kohan. (2004). Wilderness Programs: Principles, Possibilities and Opportunities for Intervention with Dropout Adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 33(2: 115-136.

Rubin, D. M., O'Reilly, A. L. R., Luan, X. Q., & Localio, A. R. (2007). The Impact of Placement Stability on Behavioral Well-Being for Children in Foster Care. Pediatrics, 119(2), 336-344.

Swanson, Christopher and Barbara Schneider. (1999). Students on the Move: Residential and Educational Mobility in America's Schools. Sociology of Education, 72(1), 54-67.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1970-2005. Characteristics of Population, Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S.

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1994). Residential Care: Some High-Risk Youth Benefit, But More Study Needed. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.