- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Paleontology

Resurrecting Giants: An Interview with Jason Poole

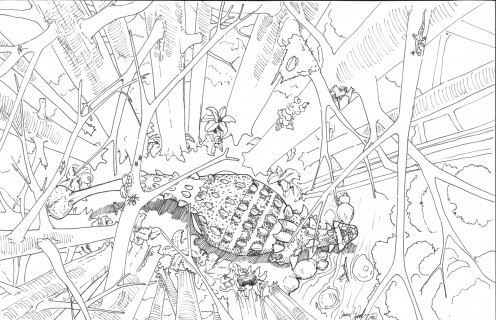

Dr. Jason Poole is a paleontologist at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia, where he manages the museum's dinosaur hall and fossil preparation lab. He has participated in fossil-finding expeditions from the Gobi Desert to Patagonia. Dr. Poole is also a professional artist who has contributed paleontology-related illustrations to publications like The National Geographic and Science, as well as science documentaries like Dino Autopsy (National Geographic Channel, 2008).

I met with him last week to discuss his work in the field, the lab, and at the drawing board.

What sparked your interest in paleontology?

Collecting fern fossils in upstate Pennsylvania and reading comic books where dinosaurs played a part. Marvel comics, especially.

Did your involvement in visual art come from these interests or did it precede it?

I started drawing from Marvel. Then it collided with fossil collecting and realizing that everything we know about dinosaurs comes from fossils. I learned to draw everything in high school, but drawing dinosaurs didn't re-emerge till afterwards. My interest in reading about them never waned, though.

What’s been the biggest surprise in your career as a paleontologist?

For me, the biggest surprise has been working with volunteers and part-time staff and teaching them fossil preparation. Coming up, I thought it would be field work. And I do enjoy field work, but it becomes so much cooler when you see someone else's mind at work and see them realize something about deep time.

How have developments in technology (especially digital technology) directly affected your work?

Computers, the Internet and the ability to store so much information give me new avenues for allowing my artwork to be seen.

I'm still not a big fan of digital artwork. It's funny, I don't know why. I just have a preference for squishing paint and pencil lines. There is a lot of good digital work out there, but it loses some of the romance for me.

You’ve also participated in the discovery and description of two of the largest known dinosaurs—Paralititan, and more recently, Dreadnoughtus. Could you tell us about each of these experiences?

As far as being in the field, Egypt was my first dig outside of the U.S. It had many life-changing moments and Paralititan was certainly one of them. And Patagonia is one of the best places in the world. There's nothing not to love--beautiful place, people, dinosaurs, great steak and great wine.

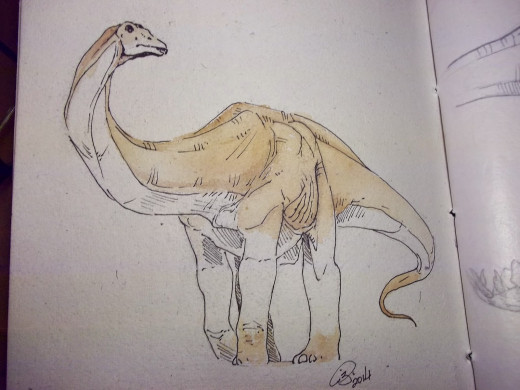

I really enjoy sauropods. We've also uncovered a third, called Suuwassea [from Late Jurassic Period of Montana].

A large part of these projects has been fossil illustration and I'm very fortunate to be working with people who have great backgrounds in science and play to their strengths. Matt Lamanna and Jerry Harris are intellectually encyclopedic and able to use facts and see new research possibilities. I thoroughly enjoy working with Ken Lacovara in the field as well. It's always fun to watch how their minds work. There has to be creativity for visualizing how things work and to see where they're going.

Do you have any direct artistic influences?

Yes: Frank Franzetta. I've always loved his figures and how they're not super-muscled or posed, as well as his linework and his handling of moody colors.

Charles R. Knight. His sketchbooks are incredible and his artwork is beautiful.

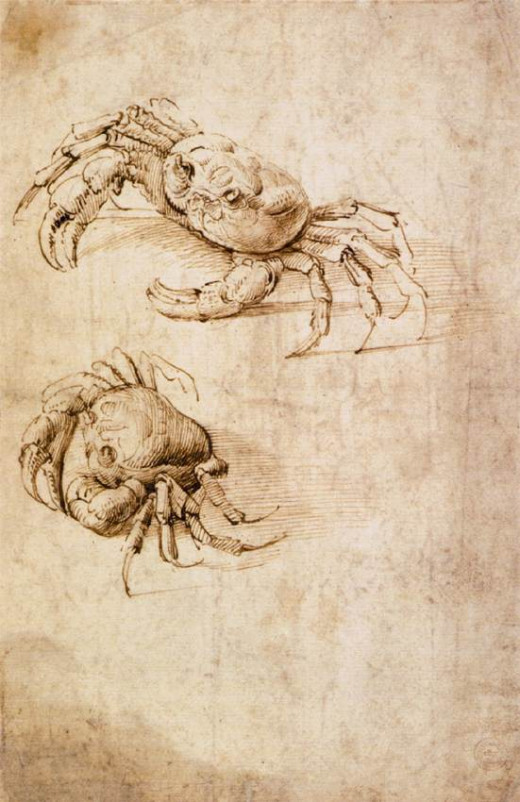

And seeing Leonardo da Vinci's sketches changed my life. He had the ability to take an object like a blade of grass and get it on the paper in a way that showed a depth of understanding and a sense interest and awe in the object. Definitely a thinking artist that used art to understand things.

As for people alive today, [I like] James Gurney for his inclusive nature and lifestyle in art. While many artists are protective and like to hide their tricks, he takes all the things that he's learned and shares them. He enjoys what he does and learning from other people.

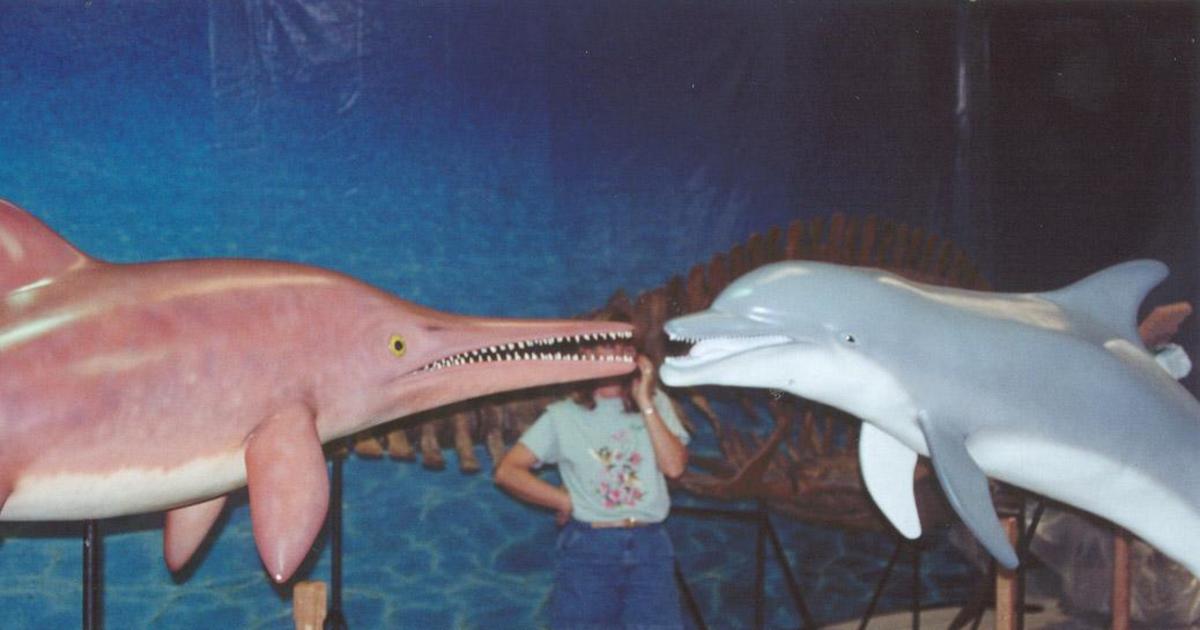

And Gary Staab, both for his 2-D and 3-D work. Phenomenal work, brilliantly nice guy.

What is your preferred medium and why?

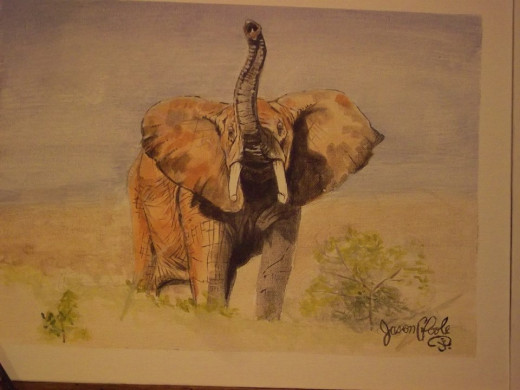

I have two: Pen and ink, and acrylic [paint]. Pen and ink is largely about fooling the eye into seeing something that captures texture, contour, and shadow all with lines, and that's really fun. Acrylic gives me a freedom to utilize and explore color in very graphic or painterly ways, depending on the story I want to relate.

Which creatures (both living and extinct) do you enjoy depicting the most?

My go-tos for extinct animals are Tyrannosaurus rex and Apatosaurus. As for living animals, I love elephants. Drawing people who don't conform to the norm of beauty is more fun and real than those in Sports Illustrated, and elephants are like that for the animal world.

What is more challenging to re-create--long-extinct animals or long-extinct environments?

Long-extinct environments can be more challenging when you're really trying to get the players of an ecosystem right. Finding the source material can be very difficult. I would love for there to be a book breaking down all the fossil formations, how they changed, and what was living there, though there are good ones out there.

When it comes to extinct animals, the more we learn, the more we have to change our view of them.

And do you ever find it a challenge balancing artistic freedom with scientific accuracy?

Yes. There are always things just understood by people with a deep background in research. You make assumptions as you go along and may not explain the importance of a [particular animal's] feature. When I work on Devonian things with Ted Daeschler, I have be to very, very thorough about the questions I ask, just so that I don't miss the details that are important.

I did a project a while back with National Geographic and learned a lot about things I did in my dinosaur drawings that I understood but that animators did not. It's interesting being on the other side of that. It helps me understand what questions I need to ask in scientific illustrations.

There are two types of paleoart: Reconstructing an animal, and representing that animal as a living thing. Perhaps a bit of fantasy is needed for the second type.