Review of "The Bearded Lady and the Shaven Man: Mona Lisa, Meet Mona/Leo"

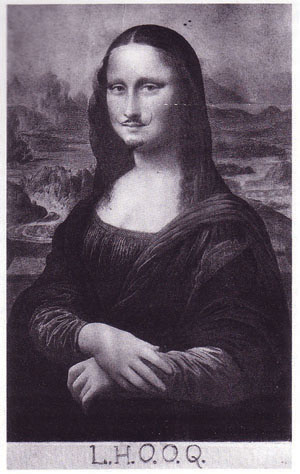

In Antoinette LaFarge’s article “The Bearded Lady and the Shaven Man: Mona Lisa, Meet Mona/Leo” the author compares Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. with Lillian Schwartz’s discovery of similarities between the Mona Lisa and a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (and the subsequent computer piece Mona/Leo which puts those images side by side). She refers to one analysis of L.H.O.O.Q. that states that the image is “hermaphroditic” in that a seemingly female figure is being shown with a male attribute—a moustache (379). She also talks about a view of the image as being one that indicates a female figure exposed, with the hair of the moustache being symbolic of pubic hair (379). L.H.O.O.Q., LaFarge argues, was not an attempt to desecrate the Mona Lisa, but to make it more culturally relevant in modern times (380).

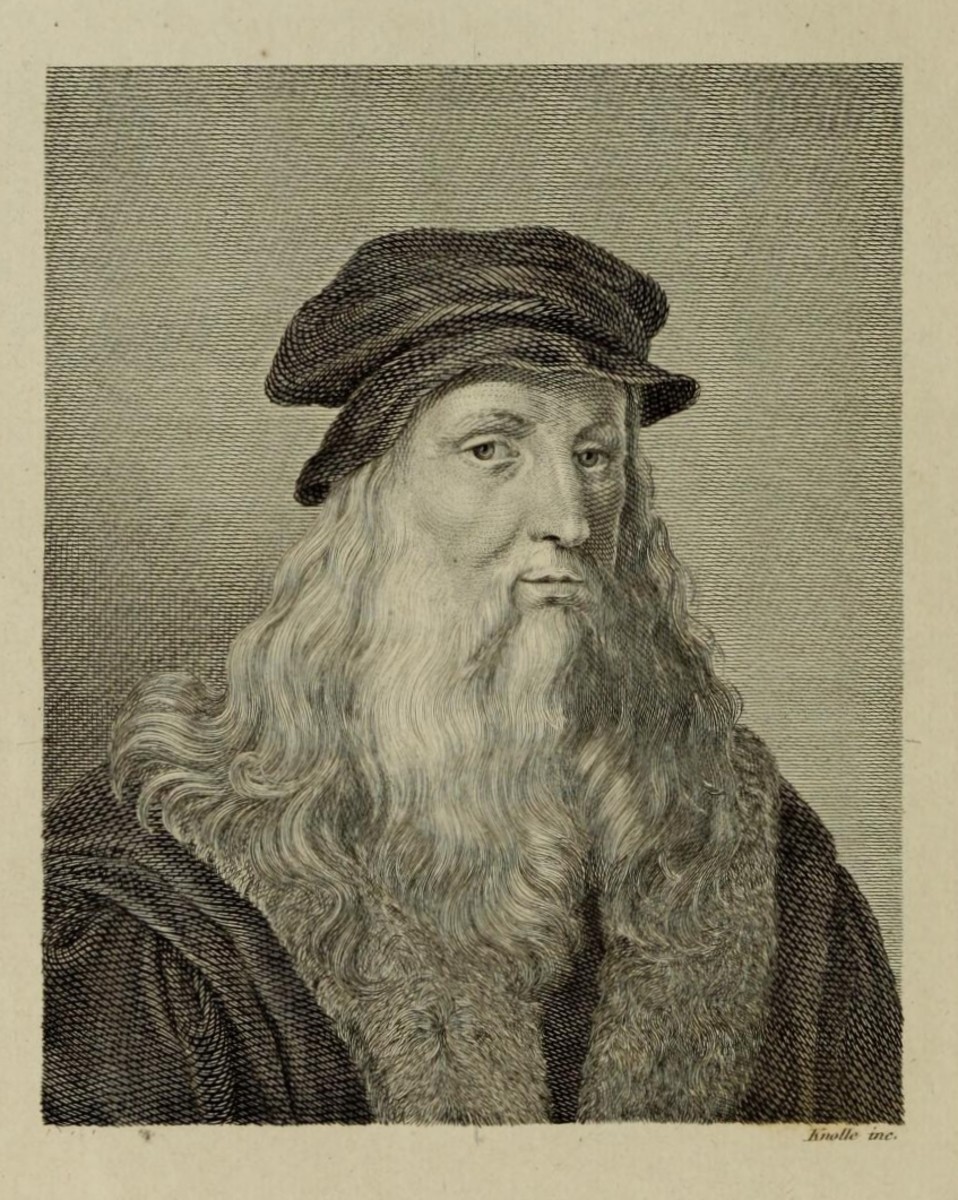

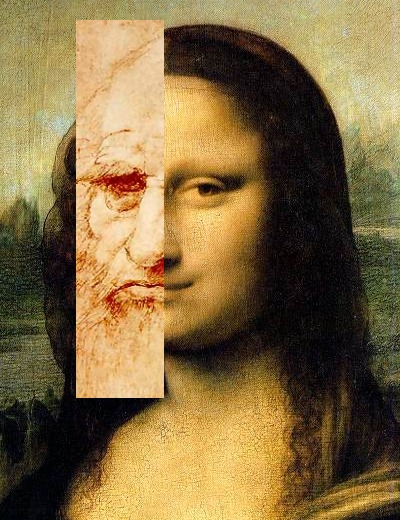

Schwartz continues this act through a project in which she would “compare and combine images of artists with digitized versions of their work, especially self-portraits” (380). In doing so, Schwartz accidentally stumbled across persuasive similarities between Mona Lisa and a self-portrait of Leonardo himself. Later X-ray evidence involving the discovery a second painting beneath the surface of the Mona Lisa shows that the portrait began as a drawing of Isabella, Duchess of Aragon, whose face is different from the one in the final product (380). All this combines to show that the main model for Mona Lisa may have been Leonardo himself.

LaFarge goes on to discuss how Mona/Leo and L.H.O.O.Q. are examples of the bearded lady archetype and how Mona Lisa and L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (a follow-up to Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. sans moustache) are examples of the shaven man archetype (382). Thus, LaFarge explains, “this sequence transforms Mona Lisa from a woman into a false man (L.H.O.O.Q.) and then into a real man (Mona/Leo) and then into a false woman (Mona Lisa again)” (381).

LaFarge ends her exploration of these pieces by musing about whether computer art (like the digitally created Mona/Leo) should be considered a mode or a medium and whether or not Duchamp himself was a precursor to this kind of creativity in the digital age (382).

LaFarge’s argument is interesting and a worthwhile one to make. Her relation of Schwartz’s discoveries and the X-ray drawing found under the Mona Lisa are particularly persuasive. She does not, however, bat away all questions of her claim. It seems a bit conspicuous to say that Schwartz’s discoveries were “accidental” when her initial project was to compare artists with their self-portraits. Surely some underlying notion of how artists portray themselves and how their sense of self comes out within their art must’ve been the area of inquiry that led to such a project in the first place, so that takes some of the edge off of this claim of “surprise” discovery. Not only that, this is an experiment that lacks comparison—or at least comparison that is mentioned. Seeing how other artists' portraits of people besides themselves compare to their own self-portraits would be especially illuminating in this case. It is not unreasonable to assume that an artist might put themselves into their work, consciously or otherwise, as an aspect of self-reflection or simply the fact that they are their own most readily available model of humanity. Aspects of Leonardo himself showing up in the Mona Lisa need not be taken as evidence of some conspiracy or joke to portray himself in drag, but as an example of the fact that artists self-reflect in their work. These counter-arguments were not answered or even brought up. In fact, counter-arguments in general are not brought up for the main issue of the Mona Lisa being modeled after Leonardo himself—it is presented as fact.

This article is fairly accessible and its brevity allows it to maintain the reader’s attention. It is not terribly jargon-filled, but at the same time it could’ve stood to gain something from taking the time to define and give historical backing for the archetypes of the bearded lady and the shaven man. These archetypes are in the title—they are important to LaFarge’s argument—but they remain relatively unexplored and their impact on gender and identity is a surface that is only just barely scratched in this article, which is a shame. She comes the closest to analyzing this concept when she talks about the shaven man archetype being indicative of “male narcissism” and “self-love,” but this exploration is relatively brief (381).

What’s more, for a short article this piece is not terribly focused. The main argument seems to concern the fact that both L.H.O.O.Q. and Mona/Leo explore the bearded lady and shaven man archetypes, but the last section of the article diverges into talks of computer-based art and how it should be catalogued and understood. This conversation is relevant to a general comparison of L.H.O.O.Q. and Mona/Leo as their difference in form and practice changes how they can be viewed; however, this conversation is, strictly speaking, tangential when it comes to the main analysis of how gender and identity works among Mona Lisa and Mona Lisa off-shoots. For a rather short article such as this one, to take such a sharp turn into an only somewhat related topic right at the end is jarring and undercuts the main points the author is trying to get across.

As it stands, this piece might have some value for use in a research paper because it can deliver some concise quotes on the subject of gender and the Mona Lisa. However, in terms of its position as a piece of evidence for making an argument about the Mona Lisa, it seems that further exploration would be required to get a fuller picture and deep analysis of the gender implications being considered here.

References

LaFarge, Antoinette. “The Bearded Lady and the Shaven Man: Mona Lisa, Meet Mona/Leo.” Leonardo, Vol. 29, No. 5, Fourth Annual New York Digital Salon, 1996, pp. 379-383.