- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

Rickenbacker: American Ace of Aces

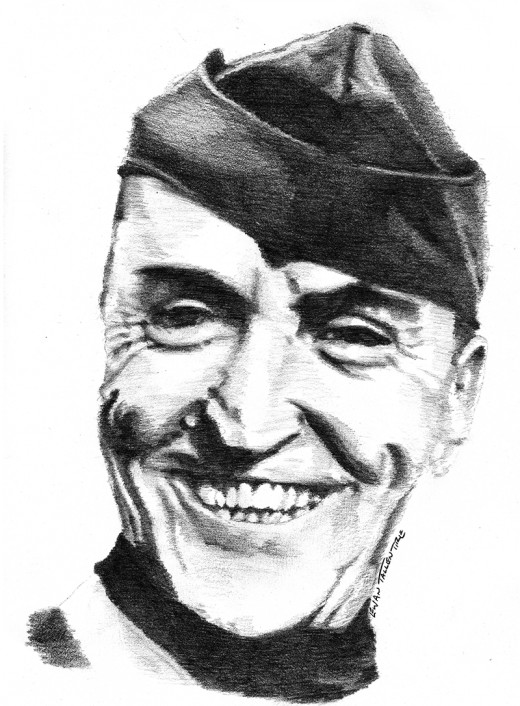

Eddie Rickenbacker

Rickenbacker's flying brought even more fame than his driving

Eddie Rickenbacker, already famous as a race car driver, became much more famous as American Ace of Aces in the few months he had at the front in World War I.

Rickenbacker the German spy

Eddie Rickenbacker went to England the winter of 1916-1917, and on landing was challenged as a German spy, based on the reporter's story from his racing days that he was really a German baron. His entry to England was delayed a while, but eventually he convinced them to let him work designing and building a team of racing cars. When he could, he talked to some of the English pilots who had already been at the front and now were back teaching new pilots. Getting to know the English convinced Rickenbacker that America should join the war, and that he should be flying against the Germans.

On February 3, 1917, Germany and the US broke off relations, and Americans were supposed to get out of Europe. On the boat trip home, Rickenbacker found he was still being followed as a German spy.

Immediately upon arriving in America he started speaking in cities all over the country about why America should join the war. After speaking all over the country, in Los Angeles a British agent introduced himself and said he had been following Rickenbacker the whole way, but finally he and the British government were fully satisfied Rickenbacker was not a German spy.

Yet another near-death experience for Rickenbacker

The man who raced fast cars and flew the first warplanes came closest to death in those years because of a tonsillectomy - an artery was cut during the operation. But bleeding to death seemed too easy; Rickenbacker was always determined to do the difficult thing, and so he fought to live as doctors fought to save him.

Race car drivers would make good pilots

Perhaps the weakness of recovering kept him from convincing the Army that they should use race car drivers as pilots. It made sense; these were men who knew machines, speed, and teamwork. But the Army thought pilots should be under 25 and have a college education, and should not be too familiar with machines. If they knew their engine wasn’t working well, it might make them afraid to go into combat.

Somehow, Eddie Rickenbacker, who was 27, an expert with machines, and educated only by correspondence course since the age of 13, managed to become not only a pilot, but America’s top ace. The many problems he had with his aircraft at the front did not seem to stop him. One wonders how the history of World War I might have been different if Rickenbacker’s recommendation had been followed.

Rickenbacker

Pilot training in 1917

In May 1917 Rickenbacker had the chance to get to France ahead of American troops generally, and jumped at the chance, missing a car race so as not to miss the war. Reporters in France thought that obviously Eddie Rickenbacker should be General Pershing’s staff driver, and reported it that way, but he never was. It was Billy Mitchell whom Rickenbacker often drove. Mitchell, who became a general during WWI but was later demoted and court-martialed for the way he insisted on the need for an air force separate from the Army, is now considered a hero of the U.S. Air Force. But along the way, Mitchell turned out to be useful for getting Rickenbacker into pilot training.

Pilot training started with a lecture, then solo practice steering a wingless airplane on the ground. On his first actual flight, Rickenbacker missed hitting the hangar by a few feet before he got enough speed to get the plane in the air. After 17 days, and 25 hours flying time, Rickenbacker was considered a pilot and first lieutenant in the Signal Corps.

In fact, with that wealth of experience flying, he became the engineering officer for a school to train new flyers. This school had a graveyard on the field, for those who died in training.

Advanced pilot training, in a boat

Rickenbacker’s new commander was a Major “Tooey” Spaatz, who after the war demonstrated the possibilities of mid-flight refueling with the Question Mark airplane. Later he became the first Chief of Staff of the USAF.

Rickenbacker was making contacts in all sorts of high places - for good or for bad. The American aviators newly arriving in France were mostly from Ivy League universities, and there was friction between them and 7th-grade dropout Eddie Rickenbacker. He greatly enjoyed the opportunity one day to send them all out to the field to pick up rocks (to keep the rocks from being kicked up and damaging the propellers). But eventually he decided they were a “fine bunch of kids”, of whom many became “excellent flyers”.

Rickenbacker still wanted to get into combat, but was useful where he was and had a hard time getting released for combat duty. When he finally was released, he started his shooting training – standing in a boat, firing a 30-caliber rifle at a target towed by another boat. Then he got to fly a Nieuport, shooting at a target pulled by a French plane. The French were not impressed when he shot the tow rope in two.

Finally, in March 1918, over a year after being sent home from Europe, he was trained enough to go to the famous 94th Aero Pursuit Squadron, which he eventually commanded. This squadron still exists today in the USAF, and is also known as the Hat-in-the-Ring Squadron, for when Uncle Sam threw his hat in the ring for World War 1.

The Question Mark being refuelled

A slow introduction to the front saved lives

At first the squadron didn’t have guns (and also at first, the French didn’t realize it, and flew with the Americans for a while before they realized their companions would be no help if a fight developed!)

Although he was frustrated that he didn’t see combat immediately, Rickenbacker later realized that time of learning to fly at the front gave him and his fellow pilots experience that saved their lives. It seemed if one could survive the first few days at the front, one could learn enough to continue surviving, and even start downing enemy planes. (Rickenbacker points out that the thought at the time is of shooting down the enemy plane, not killing the man in it; in fact, he was happy if he found out that the German pilot had survived.) The most dangerous time was a pilot's first flights, and early victory often led to excessive confidence and early death.

Some cultural differences between nations were evident in the air: Rickenbacker said the French were cautious, the British were the most daring, the Germans liked to fly in packs, and Americans preferred every-man-for-himself combat.

Raoul Lufbery

Parachutes and cowardice

One of Rickenbacker’s pet peeves seems to have been that they were not issued parachutes, for fear that if the pilot had a parachute, he would jump out of a perfectly good (and expensive) airplane. The Germans had parachutes for part of the war, but Rickenbacker points to several great pilots, including a hero of his, Raoul Lufbery, whose lives would have been saved by a parachute.

The thinking on parachutes sounds much like the thinking on not teaching pilots about mechanical details. In fact, Rickenbacker notes that the bravery it took to fly was different from the bravery it took to go into combat. So maybe a pilot with an engine problem wouldn't want to go into combat, but some pilots who were good flyers with good machines also didn't want to go into combat. Such pilots did not stay in the squadron; making them go into combat anyway would not have resulted in anything but their death. They would probably bring more risk than help to their own side.

Rickenbacker takes the Hun out of his name

Being grounded with a fever in June gave Rickenbacker time to think about tactics and machines, and resulted in better methods of aerial combat and fewer jammed guns in the squadron.

During his time in combat, Rickenbacker started spelling his name with a “k” instead of “Rickenbacher”, and the reaction in the US was “Eddie Rickenbacker has taken the Hun out of his name”. After that, the rest of the Rickenbacher family pretty much had to change spellings also! (One result was the name of the Rickenbacker guitar company, started by a distant relative of Eddie Rickenbacker.)

Billy Mitchell

Largest air force ever assembled

In September 1918 Billy Mitchell made the first-ever assault using air and ground power together. He used the largest air force ever assembled to date, 400 observation planes, 400 bombers, and 700 fighters, to support 500,000 ground troops attacking the German salient at Saint-Mihiel. The aircraft were to both protect Allied supply lines from German aircraft, and cut off the rear of the German ground force. The latter they did by shooting at horse-drawn artillery, causing a half-mile of traffic jam.

More Rickenbacker stories

Rickenbacker did not get to a combat squadron until March 1918, had no guns through most of April, and was out with a mastoid infection for a lot of the summer of 1918. He really had very little time in combat, but he had so many victories in that time that nobody in the war outscored him for victories per hour of combat. There are many more interesting war stories of his time at the front in his book Fighting the Flying Circus.

Eddie Rickenbacker was awarded the Medal of Honor, which is on display (as the museum copy; the actual medal may only be displayed by the individual or family) at the Vintage Aero Flying Museum near Denver.

Rickenbacker with aircraft

Armistice Day: November 11th, 1918

Skipping to the end of the war (past a lot of good stories best told by Rickenbacker) - Eddie Rickenbacker had an amazing view of what happened on November 11th, Armistice Day.

Nobody was supposed to be flying that day, but Rickenbacker took off anyway. Flying at less than 500 feet, he saw Germans and Americans in the trenches, prepared to kill each other. Rickenbacker could see Germans occasionally firing toward him and there were bullet holes in the plane when he landed.

I glanced at my watch. One minute to 11:00, thirty seconds, fifteen. And then it was 11:00 A.M., the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. I was the only audience for the greatest show ever presented. Brown-uniformed men poured out of the American trenches, gray-green uniforms out of the German. From my observer’s seat overhead, I watched them throw their helmets in the air, discard their guns, wave their hands. Then all up and down the front, the two groups of men began edging toward each other across no-man’s-land. Seconds before they had been willing to shoot each other; now they came forward. Hesitantly at first, then more quickly, each group approached the other.

Suddenly gray uniforms mixed with brown. I could see them hugging each other, dancing, jumping.

--Edward Vernon Rickenbacker, Rickenbacker (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967), 159

Even more amazing, in the French sector, where they had been fighting Germans for four years, there was hugging and kissing on both cheeks.

The Great War was over. Never again would there be such a war...not for a few years, anyway.