Roman Gladiators

Gladiators were professional combatant in ancient Rome. The gladiators originally performed at Etruscan funerals, no doubt with intent to give the dead man armed attendants in the next world; hence the fights were usually to the death. At shows in Rome these exhibitions became wildly popular and increased in size from three pairs at the first known exhibition in 264 BC (at the funeral of a Brutus) to 300 pairs in the time of Julius Caesar (d. 44 BC). Hence the shows extended from one day to as many as a hundred, under the emperor Titus; while the emperor Trajan in his triumph (AD 107) had 5,000 pairs of gladiators. Shows were also given in other towns of the Roman Empire, as can be seen from the traces of amphitheatres. (Alan Baker, 2002)

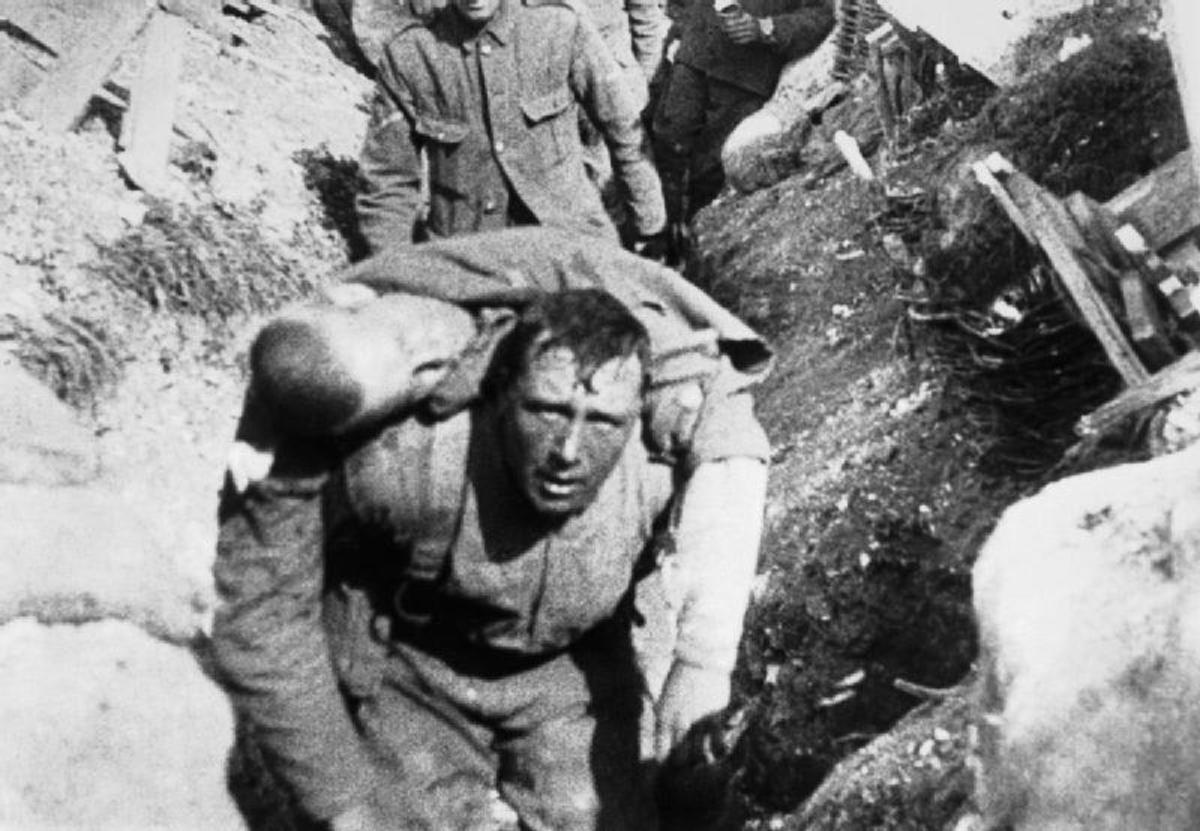

But today when criminals get caught committing a crime they get sent to jail or get sentenced a probation. They may be put in prison for two years or twenty years. One may believe that these sentences are too vulgar or mean. However, in 44 B.C. criminals or slaves were to be sent to prison camps to train to fight other prisoners like themselves. Instead of serving time the prisoner had to fight to stay alive. (Alan Baker, 2002)

Gladiators were sent to schools which were both prison camps and training centers to learn the basics of fighting. There are four stages of training. In the first stage they use wooden swords and practice moves on straw men or wood posts. Second, they practice against other prisoners with wooden swords. Next, they get to use heavy iron weapons against each other. These weapons didn’t inflict much damage to the opponent. In the fourth stage the gladiators get their real weapons and practice in air.

Gladiator fights began when two brothers had six of their slaves to fight each other to please the gods. More and more fight started to take place at funeral, and the fights grew larger than just six people. Ceaser had five–hundred men, thirty cavalrymen, and twenty battle elephants fight against each other. Later on Ceaser had a huge artificial lake made and had one–thousand sailors and two–thousand oarsmen to battle.

Mostly males, gladiators were slaves, condemned criminals, prisoners of war, and sometimes Christians. Forced to become swordsmen, they were trained in schools called ludi, and special measures were taken to discipline them and prevent them from committing suicide. One gladiator, Spartacus, avenged his captivity by escaping and leading an insurrection that terrorized southern Italy from 73 to 71 BC. (James Duffy, 2007)

A successful gladiator received great acclaim; he was praised by poets, his portrait appeared on gems and vases, and patrician ladies pampered him. A gladiator who survived many combats might be relieved from further obligation. Occasionally, freedmen and Roman citizens entered the arena, as did the insane Emperor Commodus

There were various classes of gladiators, distinguished by their arms or modes of fighting. The Samnites fought with the national weapons—a large oblong shield, a visor, a plumed helmet, and a short sword. The Thraces (“Thracians”) had a small round buckler and a dagger curved like a scythe; they were generally pitted against the mirmillones, who were armed in Gallic fashion with helmet, sword, and shield and were so called from the name of the fish that served as the crest of their helmet. In like manner the retiarius (“net man”) was matched with the secutor (“pursuer”); the former wore nothing but a short tunic or apron and sought to entangle his pursuer, who was fully armed, with the cast net he carried in his right hand; if successful, he dispatched him with the trident he carried in his left. There were also the andabatae, who are believed to have fought on horseback and to have worn helmets with closed visors—that is, to have fought blindfolded; the dimachaeri (“two-knife men”) of the later empire, who carried a short sword in each hand; the essedarii (“chariot men”), who fought from chariots like the ancient Britons; the hoplomachi (“fighters in armour”), who wore a complete suit of armour; and the laquearii (“lasso men”), who tried to lasso their antagonists. (Eckart Kohne, 2002)

The most entertaining form of battle was cavalry battles. Romans liked them because they were fast paced and took place all around the arena. Another liked form of battle was small scale sea battles. The arena would be flooded by the Tiber River. Oarsmen and sailors would be put into teams and fight other gladiators like themselves. The biggest sea battle ever was when Claudius had nineteen-thousand men reenact a battle between Rhodes and Sicily.

Animals were a big part of the gladiator era. The gladiators fought bulls, lions, panthers, tigers, leopards, and elephants. The animal fighters wore only a linen tunic and carried a long bladed spear. Sometimes the Romans would have animals fight other animals. Elephants fought rhinos and wild bison, bison fought bears and bears fought lions. Sometimes the animals would get a treat which were criminals, Jews, runaway slaves, or Christians. These people were sent in the arena without protection. (Katherine Frew, 2005)

Lottery tickets were sold frequently at the arena. Fans would go at intermissions during the contests and purchase these tickets. Sometimes spectators would climb over one another and even fought for the tickets. The prizes were the reason everyone fought. The prizes varied from wine, cash, jewels, animals, and even estates.

The shows were announced several days before they took place by bills affixed to the walls of houses and public buildings; copies were also sold in the streets. These bills gave the names of the chief pairs of competitors, the date of the show, the name of the giver, and the different kinds of combats. The spectacle began with a procession of the gladiators through the arena, and the proceedings opened with a sham fight (praelusio, prolusio) with wooden swords and javelins. (Katherine Frew, 2005)

The signal for real fighting was given by the sound of the trumpet, and those who showed fear were driven into the arena with whips and red-hot irons. When a gladiator was wounded, the spectators shouted “Habet” (“He is wounded”); if he was at the mercy of his adversary, he lifted up his forefinger to implore the clemency of the people, to whom (in the later times of the Republic) the giver left the decision as to his life or death. If the spectators were in favour of mercy they waved their handkerchiefs; if they desired the death of the conquered gladiator they turned their thumbs downward. (This is the popular view; another view is that those who wanted the death of the defeated gladiator turned their thumbs toward their breasts as a signal to stab him, and those who wished him to be spared turned their thumbs downward as a signal to drop the sword.) The reward of victory consisted of branches of palm, and sometimes of money.

If a gladiator survived a number of combats he might be discharged from further service; he could, however, reengage after discharge. On occasion gladiators became politically important, because many of the more turbulent public men had bodyguards composed of them. This of course led to occasional clashes with bloodshed on both sides. Gladiators acting on their own initiative, as in the rising led by Spartacus (q.v.) in 73–71 BC, were considered still more of a menace.

Gladiators were drawn from various sources but were chiefly slaves and criminals. Discipline was strict, but a successful gladiator not only was famous but, according to the satires of Juvenal, enjoyed the favours of society women. A curious addition to the ranks of gladiators was not uncommon under the Empire: a ruined man, perhaps of high social position, might engage himself as a gladiator, thus getting at least a means of livelihood, however precarious. One of the peculiarities of the emperor Domitian was to have unusual gladiators (dwarfs and women), and the half-mad Commodus appeared in person in the arena, of course winning his bouts.

To be the head of a school (ludus) of gladiators was a well-known but disgraceful occupation. To own gladiators and hire them out was, however, a regular and legitimate branch of commerce.

With the coming of Christianity, gladiatorial shows began to fall into disfavour. The emperor Constantine I actually abolished gladiatorial games in AD 325, but apparently without much effect since they were again abolished by the emperor Honorius (393–423) and may perhaps even have continued for a century after that.