"Saving Time": An Introductory Overview on the Cross-Cultural Perceptions of Time

While Spain unified with Portugal under the crown of Philip II and the Anglo-Spanish War raged on either side of the Atlantic, a singular gentleman, seemingly far removed from the numerous watersheds that came to define the end of the 16th century, sat in a shaded pew of a cathedral in Pisa and idly observed a swinging chandelier. This lackadaisical observation although soon transformed into a fervent interest, when, with fingers on his pulse, the man recognized a distinction between the period which it took for the chandelier to swing one full cycle and how this fact stood independent of the amplitude through which it swung. With his seemingly inconsequential revelation, Galileo Galilei began laying the groundwork for the accurate keeping of a long-controversial element: time. But this feat did not offer a solution for most other issues that time presented, including what it actually was; was it physical, a trick of the mind, or perhaps even non-existent? The subjectivity on the issue of time makes it an impossible theory to deem universally acceptable, and every culture, both ancient and contemporary, has attempted to domesticate this abstract concept through creating their own individual understanding of the term, and through various means of both mental and biological adaptations.

Still, the scientific definition does allow for a possible designation of a specific origin of time; that found in the tool making capabilities of 2 million year old Australopithecus. The manufacturing and re-working of these implements suggests the conscious acknowledgement that they would serve as items to meet future needs. This was more or less, an example of foresight. The advent of language then allowed for further capabilities in not only expressing, but thinking about things that occurred in -for the lack of better terms- the past, present, and future (Roeckelein, 4).

The ambiguousness of time has although not halted the formulation of generally accepted scientific definitions to attempt to make this concept tangible. In simplest terms, published definitions of time all suggest of a continuum that lacks spatial dimensions and measures successive events throughout past, present, and future.[1] But for the Piraha tribe of Southwestern Brazil, there are no words that describe time beyond a single day; there are no concepts of past and future (Zimbardo, 33). And for 14th and 15th century Chinese Civilization, time was regarded as having different intervals, which stood as separate units of discontinuous time (Roeckelein, 5). With only two cultural groups considered, the scientific definition has already encountered cultural-bound opposition, making it evident that there is no universally competent means to encapsulate the characterization of time.

With the dawn of the first great civilizations came further attempts at modifying time, as well as some of the first documented endeavors at adaptation. The Ancient Egyptians, for instance, had an intense correlation between nature al and social events, most of which relied solely on the annual flooding of the Nile River, which, with astronomic observances, resulted in a twelve month civil year containing 360 days (Whitrow, 26). By the 2nd Millennium B.C, Hindu cosmology had introduced the concept of cyclic time, in which the universe undergoes repeated cycles (Lewis, 403). And with the birth of Classical Antiquity evolved some of the first extensive thought processes on the mystery of time, debated by great minds such as St. Augustine and Parmenides.

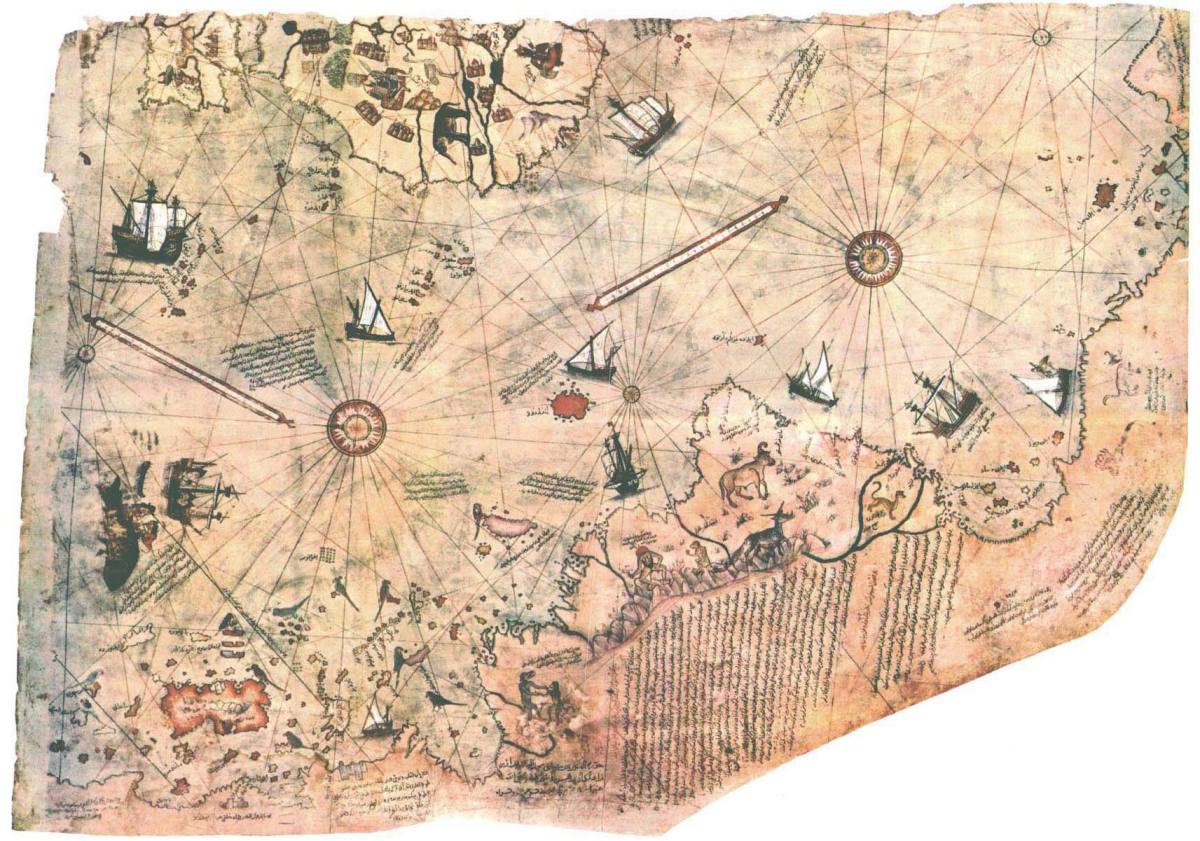

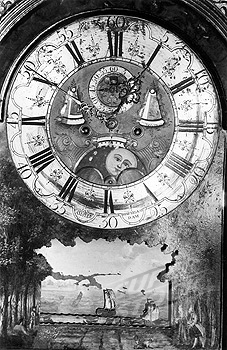

The Middle Ages then provided five distinct modes of understanding time: computational, or scientific, philosophical, mechanical, astrolabic, and kalendric, all of which manifested the increasing awareness of the problematic aspects of time keeping (Poster, 6). The Renaissance and Scientific Revolution that followed produced further insights on the measuring of time, such as those given by the aforementioned Galileo, and new theories concerning the concept of time, as Newton did in his declaration for absolute time.

Over the next 500 years, philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists, including Immanuel Kant, Adolf Grünbaum, Michael Dummett, and Einstein, continuously developed theories on the many aspects of time, giving the modern Western world its mainstream notion of the concept. But what of the remainder of the world, where clocks do not dictate a scheduled existence? What of the cultures in which the phrases “spending time” and “wasting time” hold absolutely no relevance in every day happenings? What of the societies who live simultaneous within two different states of time?

For some, time, as proposed by the Western world, is close to non-existent. The Hopi, for instance, have a language that according to Benjamin Lee Whorf, “contains no words, grammatical forms, constructions, or expressions that refer to time or any of its aspects,” (Falk, 87). While they may not have any vocabulary to suggest the changing of tenses, the Hopi although still exhibit practices, such as annual ceremonies and harvests, which can only be conducted with some general concept of time. The Piraha, a Brazilian tribe, also have no terms used to designate something either in the past or future. Instead, the tribe’s lives are conducted through “event time”; instances in the environment, including the rising of the sun or tides, which allow for a basic structural system for them to follow.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Australian aborigines have not only a concept of time, but furthermore, two parallel constructions of it; one in which the natives’ lives commence as biologically intended, while simultaneously, existing eternally in the “dreaming”. In the “dream time”, an individual exists even before he or she are conceived, and continue on after death in a world that is ever present and serves as the foundation on which aboriginal society builds (Dean, 3).

It is although not only construction or existence of time that varies between cultures; there are also general differences in how it is valued. In India, believers in the Hindu faith experience life through cyclic time, meaning nothing is permanent, history is irrelevant, and time is illusionary. Perhaps the seeming endlessness of “time” in this case leads to the relative ease placed upon daily occurrences. Robert Levine, a social psychologist, recounted his stay in India, in which he spends hours waiting on trains, telephone clerks, and people, due simply to the absence of any idea that might suggest seeing time as an inconvenience or something that needs to be rushed (Falk, 98).

A stark contrast to this slow-paced environment is that of Wall Street in New York, where every second not only holds value, but also translates into money. Within the broker filled rooms of the Financial District, various sized clocks, wristwatches, digital computers, and the occasional hoarse yell announces the passage of time. Any second not spent selling is “wasted time.” An hour in which multi-tasking accomplishes three times as much allows for “time to be saved.” Here, as much as with many other urban centers of the Western World, the values of currency are directly transferred to the values placed on time.

While before, the universal attempt at explaining time concerned itself with scientific theories, time as it is viewed on Wall Street has rapidly infiltrated other cultures with its sense of urgency and import. The electronic global capital model has begun to manipulate perceptions of time, so that for many persons far removed from the Eastern Time zones accommodate the opening of the Stock Market in New York, no matter the local time of the individual’s region. With the advances made in live media coverage and telecommunications, the ability to function not only within a local time, but also within a distant time zone, has become a possibility.[2]

In the past, accommodations to time changes were made through calendar revisions, shifts of harvests, and the inventions of day-extending tools such as light bulbs. But the present trends of globalized time have led to damaging biological adaptations. The “timelessness” of the world has caused for a drastic increase in professions that require night shifts; an occupation that can lead to adverse physical symptoms, including the lack of sleep and increased hormone levels. Another instance may involve those who are drawn to the New York Stock Market for business while residing in Tokyo. The conflicting time zones may cause individuals to experience insomnia or irregular sleep cycles, while brokers who are physically headed directly to New York from Tokyo in order to personally experience the bustle of Wall Street will suffer from jet lag and other temporal orientation issues.

So what of the future? How will the globalization and strict regulation of time affect the biological cycles of humans? Perhaps human beings will regulate their bodies to such an extent that it will simply adhere to a pre-ordained schedule, meaning it will know precisely how and when to live, and eventually, how to die. Or possibly, due to the cultural perceptions that shape time, the fast-paced world will experience a drastic acceleration of their lives; a statement that definitely gives credence to the commonly used phrase “time flies.” The only thing that can be concretely stated is that time is becoming more and more economized; it is a commodity that can either be “spent”, “saved”, or “wasted”, and will eventually, just as money has a tendency to become, a useless item once its value has been forgotten.

Copyright Lilith Eden 2011. All Rights Reserved.

References

Zimbardo, Philip, and John Boyd. The Time Paradox. Free Pr, 2008. Print.

Lewis, James R. Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press, 2005. 483. Print.

Poster, Carol, and Richard Utz. Construction of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Northwestern University Press, 1997. Print.

Gell, Alfred. The Anthropology of Time. Berg Publishers, 1992. Print.

Falk, Dan. In Search of Time. Thomas Dunne Books, 2008. Print

Dean, Colin. The Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime: its History, Cosmogenesis, Cosmology, and Ontology. Victoria, Australia: Gamahucher Press, 1996. Print.

Casey, Conerly, and Robert Edgerton. A Companion to Psychological Anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005. Print.

Roeckelein, Jon. The Concept of Time in Psychology: A Resource Book and Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Pub Group, 1966. Print

[1] Definition according to Encyclopedia Britannica from its website http://www.britannica.com.

[2] This paragraph includes variations of theories made by Kevin Birth in his artile “Time and Consciousness” as published in A Companion to Psychological Anthropology by Conerly Casey and Robert Edgerton.